Tony Cragg's Laibe and the Metaphors of Clay

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

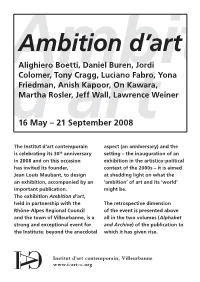

D'art Ambition D'art Alighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony

Ambition d’art AmbitionAlighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony Cragg, Luciano Fabro, Yona Friedman, Anish Kapoor, On Kawara, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall, Lawrence Weiner d’art16 May – 21 September 2008 The Institut d’art contemporain aspect (an anniversary) and the is celebrating its 30th anniversary setting – the inauguration of an in 2008 and on this occasion exhibition in the artistico-political has invited its founder, context of the 2000s – it is aimed Jean Louis Maubant, to design at shedding light on what the an exhibition, accompanied by an ‘ambition’ of art and its ‘world’ important publication. might be. The exhibition Ambition d’art, held in partnership with the The retrospective dimension Rhône-Alpes Regional Council of the event is presented above and the town of Villeurbanne, is a all in the two volumes (Alphabet strong and exceptional event for and Archive) of the publication to the Institute: beyond the anecdotal which it has given rise. Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne www.i-art-c.org Any feedback in the exhibition is Yona Friedman, Jordi Colomer) or less to commemorate past history because they have hardly ever been than to give present and future shown (Martha Rosler, Alighiero history more density. In fact, many Boetti, Jeff Wall). Other works have of the works shown here have already been shown at the Institut never been seen before. and now gain fresh visibility as a result of their positioning in space and their artistic company (Luciano Fabro, Daniel Buren, Martha Rosler, Ambition d’art Tony Cragg, On Kawara). For the exhibition Ambition d’art, At the two ends of the generation Jean Louis Maubant has chosen chain, invitations have been eleven artists for the eleven rooms extended to both Jordi Colomer of the Institut d’art contemporain. -

Artists' Lives

National Life Stories The British Library 96 Euston Road London NW1 2DB Tel: 020 7412 7404 Email: [email protected] Artists’ Lives C466: Interviews complete and in-progress (at January 2019) Please note: access to each recording is determined by a signed Recording Agreement, agreed by the artist and National Life Stories at the British Library. Some of the recordings are closed – either in full or in part – for a number of years at the request of the artist. For full information on the access to each recording, and to review a detailed summary of a recording’s content, see each individual catalogue entry on the Sound and Moving Image catalogue: http://sami.bl.uk . EILEEN AGAR PATRICK BOURNE ELISABETH COLLINS IVOR ABRAHAMS DENIS BOWEN MICHAEL COMPTON NORMAN ACKROYD FRANK BOWLING ANGELA CONNER NORMAN ADAMS ALAN BOWNESS MILEIN COSMAN ANNA ADAMS SARAH BOWNESS STEPHEN COX CRAIGIE AITCHISON IAN BREAKWELL TONY CRAGG EDWARD ALLINGTON GUY BRETT MICHAEL CRAIG-MARTIN ALEXANDER ANTRIM STUART BRISLEY JOHN CRAXTON RASHEED ARAEEN RALPH BROWN DENNIS CREFFIELD EDWARD ARDIZZONE ANNE BUCHANAN CROSBY KEITH CRITCHLOW DIANA ARMFIELD STEPHEN BUCKLEY VICTORIA CROWE KENNETH ARMITAGE ROD BUGG KEN CURRIE MARIT ASCHAN LAURENCE BURT PENELOPE CURTIS ROY ASCOTT ROSEMARY BUTLER SIMON CUTTS FRANK AVRAY WILSON JOHN BYRNE ALAN DAVIE GILLIAN AYRES SHIRLEY CAMERON DINORA DAVIES-REES WILLIAM BAILLIE KEN CAMPBELL AILIAN DAY PHYLLIDA BARLOW STEVEN CAMPBELL PETER DE FRANCIA WILHELMINA BARNS- CHARLES CAREY ROGER DE GREY GRAHAM NANCY CARLINE JOSEFINA DE WENDY BARON ANTHONY CARO VASCONCELLOS -

A Changed World Joseph Paul Cassar

FirstSnail by Edward Allington. A Changed World Joseph Paul Cassar A Changed World is an exhibition brought people in the medical fieldand other disciplines about through the initiative and assistance of complain that they cannot keep up with the lat the British Council in Malta, and it focuses on est developments in their respective areas and the various transformations that many are those who are uneasy and suspicious British sculpture has undergone that change is out of control. over the past 40 years. It presents We live in a world ofobjects and commodities the concept of change as the that have been designed for instant death. It is process by which the future clear now that the acceleration of change has invades our lives, for change is reached such a rapid pace that it is possible ongoing without which time to open your eyes one morning to see a world would stop. totally new. The exhibition is about the In my opinion, the whole point of this exhi fantastic intrusion of novelty bition is that in the past one rarely saw a fun and newness into our exis damental change in an art style within a tence. This is the story of how man's lifetime. A style or school endured as we learn to adapt - or fail to a rule, for generations at a time. Today, the adapt - to the future. Each pace of turnover in art scarcely has time to change brings with it a need for new learning, forin us, there (Continued on opposite page) is the power to shape change. -

Press Release

For Immediate Release. Tony Cragg February 1 – March 10, 2012 Opening reception: Wednesday, February 1st, 6-8 pm. Marian Goodman Gallery is delighted to present an exhibition of new sculpture by Tony Cragg opening on Wednesday, February 1st, and continuing through Saturday, March 10th. The exhibition will feature recent sculptures in bronze, corten steel, wood, cast iron, and stone. Concurrently, and accompanying the gallery presentation, a group of large scale works will be exhibited at The Sculpture Garden at 590 Madison Avenue (entrance at 56th Street). The Sculpture Garden is open to the public daily from 8 am to 10 pm. Tony Cragg is one of the most distinguished contemporary sculptors working today. During the past year, there have been several important solo exhibitions of his work worldwide: Seeing Things at The Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas; Figure In/ Figure Out at The Louvre, Paris; Museum Küppersmühle für Moderne Kunst, Duisburg, Germany; Tony Cragg in 4 D from Flux to Stability at The International Gallery of Modern Art, Venice; It is, Isn’t It at the Church of San Cristoforo, Lucca, Italy; and Tony Cragg: Sculptures and Drawings at The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh. Cragg’s work developed within the context of diverse influences including early experiences in a scientific laboratory; English landscape and time-based art, a precursor to the presenting of found objects and fragments that characterized early performative work; and Minimalist sculpture, an antecedent to the stack, additive and accumulation works of the mid- seventies. Cragg has widened the boundaries of sculpture with a dynamic and investigative approach to materials, to images, and objects in the physical world, and an early use of found industrial objects and fragments. -

Alison Wilding

!"#$%&n '(h)b&#% Alison Wilding Born 1948 in Blackburn, United Kingdom Currently lives and works in London Education 1970–73 Royal College of Art, London 1967–70 Ravensbourne College of Art and Design, Bromley, Kent 1966–67 Nottingham College of Art, Nottingham !" L#xin$%on &%'##% London ()* +,-, ./ %#l +!! (+).+0+ //0!112! 1++.3++0 f24x +!! (+).+0+ //0!112! 1+.)3+0) info342'5%#564'7%#n5678h79b#'%.68om www.42'5%#64'7%#n5678h79b#'%.68om !"#$%&n '(h)b&#% Selected solo exhibitions 2013 Alison Wilding, Tate Britain, London, UK Alison Wilding: Deep Water, Whitworth Art Gallery, Manchester, UK 2012 Alison Wilding: Drawing, ‘Drone 1–10’, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2011 Alison Wilding: How the Land Lies, New Art Centre, Roche Court Sculpture Park, Salisbury, UK Alison Wilding: Art School Drawings from the 1960s and 1970s, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2010 Alison Wilding: All Cats Are Grey…, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2008 Alison Wilding: Tracking, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2006 Alison Wilding, North House Gallery, Manningtree, UK Alison Wilding: Interruptions, Rupert Wace Ancient Art, London, UK 2005 Alison Wilding: New Drawings, The Drawing Gallery, London, UK Alison Wilding: Sculpture, Betty Cuningham Gallery, New York, NY, US Alison Wilding: Vanish and Detail, Fred, London, UK 2003 Alison Wilding: Migrant, Peter Pears Gallery and Snape Maltings, Aldeburgh, UK 2002 Alison Wilding: Template Drawings, Karsten Schubert, London, UK 2000 Alison Wilding: Contract, The Henry Moore Foundation Studio, Halifax, UK Alison Wilding: New Work, New -

ART in AMERICA November, 1999 Shirazeh Houshiary at Lehmann

ART IN AMERICA November, 1999 Shirazeh Houshiary at Lehmann Maupin By Edward Leffingwell In her first New York solo exhibition, the London-based Iranian painter and sculptor Shirazeh Houshiary presented a series of monochromatic paintings that invited the viewer to peer closely into their graphite-inflected surfaces to discern the minute grids and vortices of calligraphy that are central to the artist's mystic contemplation. Houshiary achieves these dense matte surfaces of either white or black with an even application of Aquacryl, a concentrated, viscous suspension of rich pigment that dries to a uniformly flat finish with a barely perceptible incidence of randomly distributed pores. She then painstakingly inscribes the delicate patterns of Sufi incantations in graphite across the black surfaces, and across the white ones in graphite, silverpoint and occasionally pencil, on canvases ranging from 11 inches to nearly 75 inches square. For Houshiary, the labor-intensive paintings of this impressive show express Sufi doctrine in both their making and viewing. They involve a search for the reconciliation of opposing forces, unification with the world and the achievement of transcendence. As a kind of prayer, these complex paintings are at once contemplative and celebratory, bearing evidence of the concentration and discipline necessary to their making, and requiring quiet study or contemplation on the part of the viewer to be perceived on any meaningful level. The fine graphite calligraphy that makes up the central element in the large black field of Unknowable (1999) appears to begin at an unseen central point and spirals out in moirélike patterns, the text repeating, gracefully opening out and becoming less dense then disappearing. -

May 2016 Held an Exhibition of Tony Cragg, One of the Leading Representatives of the “New British Sculpture” Movement

UDC 7.067 Вестник СПбГУ. Сер. 15. 2016. Вып. 3 A. O. Kotlomanov1,2 “NEW BRITISH SCULPTURE” AND THE RUSSIAN ART CONTEXT 1 Saint Petersburg Stieglitz State Academy of Art and Design, 13, Solyanoy per., St. Petersburg, 191028, Russian Federation 2 St. Petersburg State University, 7–9, Universitetskaya nab., St. Petersburg, 199034, Russian Federation The article examines the works of leading representatives of the “New British Sculpture” Tony Cragg and Antony Gormley. The relevance of the text is related to Tony Cragg’s recent retrospective at the Hermitage Museum. Also it reviews the circumstances of realizing the 2011 exhibition project of Ant- ony Gormley at the Hermitage. The problem is founded on the study of the practice of contemporary sculpture of the last thirty years. The author discusses the relationship of art and design and the role of the financial factors in contemporary art culture. The text is provided with examples of individual theoretical and self-critical statements of Tony Cragg and Antony Gormley. It makes a comparison of the Western European art context and Russian tendencies in this field as parallel trends of creative thinking. Final conclusions formulate the need to revise the criteria of art theory and art criticism from the point of recognition of new commercial art and to determine its role in the culture of our time. Refs 5. Figs 7. Keywords: Tony Cragg, Antony Gormley, New British Sculpture, Hermitage, contemporary art, contemporary sculpture. DOI: 10.21638/11701/spbu15.2016.303 «НОВАЯ БРИТАНСКАЯ СКУЛЬПТУРА» И РОССИЙСКИЙ ХУДОЖЕСТВЕННЫЙ КОНТЕКСТ А. О. Котломанов1,2 1 Санкт-Петербургская государственная художественно-промышленная академия им. -

Richard Deacon. Some Time

RICHARD DEACON. EN SOME TIME 27.05 – 24.09.2017 1 The Middelheim Museum proudly presents SOME TIME, a solo show introducing work by Richard Deacon (Wales, °1949), one of Britain’s most fascinating contemporary artists. The thirty sculp- tures on display, including several recent works, are particularly 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 diverse in size, design and material. They are presented on various Braem Pavilion locations in the museum park. view plan B on p. 19 26 The exhibition has come about in close collaboration with the artist. The 28 central focus is on his sculpture Never Mind (1993), one of the Middelheim 27 29 Museum’s key works. For this show, the original wooden version has been BEUKEN refabricated in stainless steel. L A A N 55 Castle F E Deacon, master-fabricator E M DR EI H EN D EL D N I 6 L ID M 5 7 “The sculptures that I make are, in most cases, neither carved or modelled A AN 2 N LA 12 13 14 15 16 Z M HEI DEL – the two traditional means of making sculpture – but assembled from parts. MID 30 The House I am therefore a fabricator and what I make are fabrications.” BEUKEN view plan A on p.14 4 3 – Richard Deacon L A A 10 N Richard Deacon has invariably been at the forefront of the visual arts 8 11 9 scene since the 1980s. He began his training at London’s Saint Martins 1 School of Art in 1969, when the experimental vision ‘art is an attitude, not a technique’ was very much alive there. -

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000

British Art Studies July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth British Art Studies Issue 3, published 4 July 2016 British Sculpture Abroad, 1945 – 2000 Edited by Penelope Curtis and Martina Droth Cover image: Installation View, Simon Starling, Project for a Masquerade (Hiroshima), 2010–11, 16 mm film transferred to digital (25 minutes, 45 seconds), wooden masks, cast bronze masks, bowler hat, metals stands, suspended mirror, suspended screen, HD projector, media player, and speakers. Dimensions variable. Digital image courtesy of the artist PDF generated on 21 July 2021 Note: British Art Studies is a digital publication and intended to be experienced online and referenced digitally. PDFs are provided for ease of reading offline. Please do not reference the PDF in academic citations: we recommend the use of DOIs (digital object identifiers) provided within the online article. Theseunique alphanumeric strings identify content and provide a persistent link to a location on the internet. A DOI is guaranteed never to change, so you can use it to link permanently to electronic documents with confidence. Published by: Paul Mellon Centre 16 Bedford Square London, WC1B 3JA https://www.paul-mellon-centre.ac.uk In partnership with: Yale Center for British Art 1080 Chapel Street New Haven, Connecticut https://britishart.yale.edu ISSN: 2058-5462 DOI: 10.17658/issn.2058-5462 URL: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk Editorial team: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/editorial-team Advisory board: https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/about/advisory-board Produced in the United Kingdom. A joint publication by Contents Expanding the Field: How the “New Sculpture” put British Art on the Map in the 1980s, Nick Baker Expanding the Field: How the “New Sculpture” put British Art on the Map in the 1980s Nick Baker Abstract This paper shows that sculptors attracted much of the attention that was paid to emerging British artists during the 1980s. -

(Public Pack)Agenda Document for Art Galleries Committee, 17/02/2021

Public Document Pack Art Galleries Committee Date: Wednesday, 17 February 2021 Time: 9.30 am Venue: Virtual meeting – https://vimeo.com/509986438 Everyone is welcome to attend this committee meeting. The Local Authorities and Police and Crime Panels (Coronavirus) (Flexibility of Local Authority and Police and Crime Panel Meetings) (England and Wales) Regulations 2020. Under the provisions of these regulations the location where a meeting is held can include reference to more than one place including electronic, digital or virtual locations such as Internet locations, web addresses or conference call telephone numbers. To attend this meeting it can be watched live as a webcast. The recording of the webcast will also be available for viewing after the meeting has ended. Membership of the Art Galleries Committee Councillors - Akbar, Bridges, Craig, Leech, Leese, N Murphy, Ollerhead, Rahman, Richards and Stogia Art Galleries Committee Agenda 1. Urgent Business To consider any items which the Chair has agreed to have submitted as urgent. 2. Appeals To consider any appeals from the public against refusal to allow inspection of background documents and/or the inclusion of items in the confidential part of the agenda. 3. Interests To allow Members an opportunity to [a] declare any personal, prejudicial or disclosable pecuniary interests they might have in any items which appear on this agenda; and [b] record any items from which they are precluded from voting as a result of Council Tax/Council rent arrears; [c] the existence and nature of party whipping arrangements in respect of any item to be considered at this meeting. Members with a personal interest should declare that at the start of the item under consideration. -

PRESS 2015 Eunice Tsang, 'Interview: Antony Gormley on His

PRESS 2015 Eunice Tsang, 'Interview: Antony Gormley on his HK sculpture installation, Event Horizon', Time Out Hong Kong, Hong Kong, China, 2nd December 2015. Enid Tsui, 'Stand and Consider', South China Morning Post, Hong Kong, China, 3rd November 2015 Stephen Short, ' Outside the Box', Tatler, Hong Kong, China, November 2015 Antony Gormley, 'New Roles for an Ancient Form', The Financial Times, London, U.K., 4th October 2015 Pia Capelli, 'Per inciampare nelle statue', Il Sole 24 Ore, Milan, Italy, 2nd August 2015 David Whetstone, 'Antony Gormley exhibition launches drawing project at Newcastle's Hatton Gallery', Evening Chronicle, Newcastle, U.K., 4th July 2015 Martin Gayford, 'Antony Gormley: Renaissance thinking was wrong', The Telegraph, London, U.K., 6th June 2015 Gregorio Botta, 'Antony Gormley: La nuova vita (estetica) del corpo umano', Rome, Italy, 14th June 2015 Hannah Ellis-Petersen, 'I am still learning how to make sculpture', The Guardian, London, U.K., 6th May 2015 Nicholas Forrest, 'Antony Gormley on His Epic "Human" Exhibition in Florence', Blouin Art Info, New York, U.S.A., 30th April 2015 Antony Gormley, 'The Man who made dumb objects speak', The Evening Standard, London, U.K., 8th April 2015 Francesca Pini, 'Qui a Firenze contesto la tirannia del Rinascimento', Corriere Della Sera Sette, Milan, Italy, 20th March 2015 Amy Verner, 'Antony Gormley's sculpture takes over Galerie Thaddaeus Ropac', Wallpaper*, London, U.K., 4th March 2015 2014 Alexander Sury, 'Das ist der Ort, in dem ich lebe', Der Bund, Berne, Switzerland, -

Tony Cragg Biography

Tony Cragg Tony Cragg is one of the world’s foremost sculptors. Constantly pushing to find new relations between people and the material world, there is no limit to the materials he might use, as there are no limits to the ideas or forms he might conceive. His early, stacked works present a taxonomical understanding of the world, and he has said that he sees manmade objects as “fossilized keys to a past time which is our present”. So too, the floor and wall arrangements of objects that he started making in the 1980s blur the line between manmade and natural landscapes: they create an outline of something familiar, where the contributing parts relate to the whole. Cragg understands sculpture as a study of how material and material forms affect and form our ideas and emotions. This is exemplified in the way in which Cragg has worked and reworked two broad bodies of work he calls Early Forms and Rational Beings. The Early Forms explore the possibilities of sculpturally reforming familiar objects such as containers into new and unfamiliar forms producing new emotional responses, relationships and meanings. Rational Beings examine the relationship between two apparently different aesthetic descriptions of the world; the rational, mathematically based formal constructions that go to build up the most complicated of organic forms that we respond to emotionally. The human figure being the prime example of something that looks ultimately organic eliciting emotional responses, while being fundamentally an extremely complicated geometric composition of molecules, cells, organs and processes. His work does not imitate nature and what we look like, rather it concerns itself with why we look like we do and why we are as we are.