Richard Shone Julian Opie, Imagine That It’S Raining

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

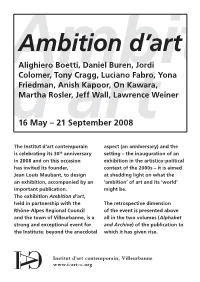

D'art Ambition D'art Alighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony

Ambition d’art AmbitionAlighiero Boetti, Daniel Buren, Jordi Colomer, Tony Cragg, Luciano Fabro, Yona Friedman, Anish Kapoor, On Kawara, Martha Rosler, Jeff Wall, Lawrence Weiner d’art16 May – 21 September 2008 The Institut d’art contemporain aspect (an anniversary) and the is celebrating its 30th anniversary setting – the inauguration of an in 2008 and on this occasion exhibition in the artistico-political has invited its founder, context of the 2000s – it is aimed Jean Louis Maubant, to design at shedding light on what the an exhibition, accompanied by an ‘ambition’ of art and its ‘world’ important publication. might be. The exhibition Ambition d’art, held in partnership with the The retrospective dimension Rhône-Alpes Regional Council of the event is presented above and the town of Villeurbanne, is a all in the two volumes (Alphabet strong and exceptional event for and Archive) of the publication to the Institute: beyond the anecdotal which it has given rise. Institut d’art contemporain, Villeurbanne www.i-art-c.org Any feedback in the exhibition is Yona Friedman, Jordi Colomer) or less to commemorate past history because they have hardly ever been than to give present and future shown (Martha Rosler, Alighiero history more density. In fact, many Boetti, Jeff Wall). Other works have of the works shown here have already been shown at the Institut never been seen before. and now gain fresh visibility as a result of their positioning in space and their artistic company (Luciano Fabro, Daniel Buren, Martha Rosler, Ambition d’art Tony Cragg, On Kawara). For the exhibition Ambition d’art, At the two ends of the generation Jean Louis Maubant has chosen chain, invitations have been eleven artists for the eleven rooms extended to both Jordi Colomer of the Institut d’art contemporain. -

Contemporary Art Society Annual Report 1993

THE CONTEMPORARY ART SOCIETY The Annual General Meeting of the Contemporary Art Society will be held on Wednesday 7 September, 1994 at ITN, 200 Gray's Inn Road, London wcix 8xz, at 6.30pm. Agenda 1. To receive and adopt the report of the committee and the accounts for the year ended 31 December 1993, together with the auditors' report. 2. To reappoint Neville Russell as auditors of the Society in accordance with section 384 (1) of the Companies Act 1985 and to authorise the committee to determine their remunera tion for the coming year. 3. To elect to the committee Robert Hopper and Jim Moyes who have been duly nominated. The retiring members are Penelope Govett and Christina Smith. In addition Marina Vaizey and Julian Treuherz have tendered their resignation. 4. Any other business. By order of the committee GEORGE YATES-MERCER Company Secretary 15 August 1994 Company Limited by Guarantee, Registered in London N0.255486, Charities Registration No.2081 y8 The Contemporary Art Society Annual Report & Accounts 1993 PATRON I • REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother PRESIDENT Nancy Balfour OBE The Committee present their report and the financial of activities and the year end financial position were VICE PRESIDENTS statements for the year ended 31 December 1993. satisfactory and the Committee expect that the present The Lord Croft level of activity will be sustained for the foreseeable future. Edward Dawe STATEMENT OF COMMITTEE'S RESPONSIBILITIES Caryl Hubbard CBE Company law requires the committee to prepare financial RESULTS The Lord McAlpine of West Green statements for each financial year which give a true and The results of the Society for the year ended The Lord Sainsbury of Preston Candover KG fair view of the state of affairs of the company and of the 31 December 1993 are set out in the financial statements on Pauline Vogelpoel MBE profit or loss of the company for that period. -

Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics Author(S): Claire Bishop Source: October, Vol

Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics Author(s): Claire Bishop Source: October, Vol. 110 (Autumn, 2004), pp. 51-79 Published by: The MIT Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/3397557 Accessed: 19/10/2010 19:54 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=mitpress. Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed page of such transmission. JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to October. http://www.jstor.org Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics CLAIRE BISHOP The Palais de Tokyo On the occasion of its opening in 2002, the Palais de Tokyo immediately struck the visitor as different from other contemporary art venues that had recently opened in Europe. -

Rachel Whiteread

RACHEL WHITEREAD Born in Ilford, Essex in 1963 Lives and works in London, UK Eduction 1985–1987, Slade School of Art, London, England 1982–1985, Brighton Polytechnic, Brighton, England Solo Exhibitions 2017-2018 Rachel Whiteread, Tate Britain, London, England 2017 Place (Village), Victoria and Albert Museum of Childhood, London, England Rachel Whiteread, Galleria Lorcan O’Neill, Rome, Italy 2015 Rachel Whiteread: Looking In, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY Rachel Whiteread: Looking Out, Luhring Augustine Bushwick, Brooklyn, NY 2014 Rachel Whiteread, Gagosian Gallery, Geneva, Switzerland Rachel Whiteread: Study for Room, Museo d’Arte Moderna di Bologna, Bologna, Italy 2013 Rachel Whiteread: Detached, Gagosian Gallery, London, England 2011 Rachel Whiteread: Long Eyes, Luhring Augustine, New York, NY Rachel Whiteread: Looking On, Galleria Lorcan O’Neill Roma, Rome, Italy 2010 Rachel Whiteread: Drawings, Armand Hammer Museum of Art and Culture Center, Los Angeles, CA; Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas, TX; Tate Britain, London, England* Rachel Whiteread, Gagosian Gallery, London, England Rachel Whiteread, Galerie Nelson-Freeman, Paris, France 2009 Rachel Whiteread, Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR WWW.SAATCHIGALLERY.COM RACHEL WHITEREAD 2008 Rachel Whiteread, Gagosian Gallery, Beverly Hills, CA Rachel Whiteread, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, MA 2007 Rachel Whiteread August Seeling Prize Exhibition, Stiftung Wilhelm Lehmbruck Museum, Duisburg, Germany Rachel Whiteread, Centro de Arte Contemporáneo de Málaga, Málaga, Spain Rachel Whiteread, Galleria -

Annual Report 2018/2019

Annual Report 2018/2019 Section name 1 Section name 2 Section name 1 Annual Report 2018/2019 Royal Academy of Arts Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD Telephone 020 7300 8000 royalacademy.org.uk The Royal Academy of Arts is a registered charity under Registered Charity Number 1125383 Registered as a company limited by a guarantee in England and Wales under Company Number 6298947 Registered Office: Burlington House, Piccadilly, London, W1J 0BD © Royal Academy of Arts, 2020 Covering the period Coordinated by Olivia Harrison Designed by Constanza Gaggero 1 September 2018 – Printed by Geoff Neal Group 31 August 2019 Contents 6 President’s Foreword 8 Secretary and Chief Executive’s Introduction 10 The year in figures 12 Public 28 Academic 42 Spaces 48 People 56 Finance and sustainability 66 Appendices 4 Section name President’s On 10 December 2019 I will step down as President of the Foreword Royal Academy after eight years. By the time you read this foreword there will be a new President elected by secret ballot in the General Assembly room of Burlington House. So, it seems appropriate now to reflect more widely beyond the normal hori- zon of the Annual Report. Our founders in 1768 comprised some of the greatest figures of the British Enlightenment, King George III, Reynolds, West and Chambers, supported and advised by a wider circle of thinkers and intellectuals such as Edmund Burke and Samuel Johnson. It is no exaggeration to suggest that their original inten- tions for what the Academy should be are closer to realisation than ever before. They proposed a school, an exhibition and a membership. -

Press Release Ryan Gander

Press Release Ryan Gander: I see straight through you 16 September – 15 October 2016 504 W 24th Street, New York For his first solo exhibition in New York in nearly ten years, British conceptual artist Ryan Gander presents a new body of work that considers the psychology of the body and questions the possibilities and limitations of figuration. A master storyteller, Gander’s complex yet playful practice is characterized by allusion, where focal points are teasingly hidden and meaning is subtly implied. Stimulated by existential queries and investigations into what-ifs, each one of his artworks acts as a vessel to tell a new story, all collectively fitting into an overarching narrative where fictions and realities collide. Mirrors with no reflection, bodiless eyes, faceless men and a self-portrait in constant motion combine to reflect Gander’s interest in the dialectics of self- awareness and the barriers to understanding. Flirtatious, cartoonish eyes follow visitors around the exhibition. Embedded not on a face but a blank wall, the eyes are animatronic, connected to motion sensors activated by movement in the room. With long, seductive lashes and coyly raised eyebrows, the work is the female counterpart to Gander’s Magnus Opus (2013), one of the artist’s most popular works to date. Dominae Illud Opus Populare (2016), on show at Lisson Gallery for the first time, has been programmed to generate every expression that can be registered through one’s eyes, from boredom and worry to curiosity and surprise. Expression is further explored through a new series of sculptures: life- size armatures of artist models in dramatic postures, arranged strategically within the gallery’s expansive exhibition space. -

Julian.Opie.Bio 2016 New.Pdf

2012 Sakshi Gallery, Mumbai, India Lisson Gallery, London, UK 2011 Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy National Portrait Gallery, London, UK Krobath, Berlin, Germany Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK (exh cat) Bob van Orsouw, Zurich, Switzerland 2010 Barbara Krakow Gallery, Boston, USA Mario Sequeira, Braga, Portugal IVAM, Valencia, Spain Galerist, Istanbul, Turkey 2009 Valentina Bonomo, Rome, Italy "Dancing in Kivik", Kivik Art Centre, Osterlen, Sweden Kukje Gallery, Seoul, South Korea (exh cat) Sakshi Gallery, Mumbai, India SCAI the Bathhouse, Tokyo, Japan Patrick de Brock, Knokke, Belgium 2008 MAK, Vienna, Austria (exh cat) Lisson Gallery, London, UK (exh cat) Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK (exh cat) Krobath Wimmer, Vienna, Austria Art Tower Mito, Japan (exh cat) 2007 Barbara Thumm, Berlin, Germany Museum Kampa, Prague, Czech Republic (exh cat) Barbara Krakow Gallery, Boston, USA King's Lynn art centre, Norfolk, UK 2006 CAC, Malaga, Spain (exh cat) Bob van Orsouw, Zurich, Switzerland Alan Cristea Gallery, London, UK 2005 Mario Sequeira, Braga, Portugal La Chocolateria, Santiago de Compostela, Spain SCAI the Bathhouse, Tokyo, Japan MGM, Oslo, Norway Valentina Bonomo, Rome, Italy 2004 - 2005 Public Art Fund, City Hall Park, New York City, USA 2004 Lisson Gallery, London, UK (exh cat) Wetterling Gallery, Stockholm, Sweden (exh cat) Kunsthandlung H. Krobath & B. Wimmer, Vienna, Austria Patrick de Brock Gallery, Knokke, Belgium Barbara Thumm Galerie, Berlin Krobath Wimmer, Wien, Austria 2003 Neues Museum, Staatliches Museum fur Kunst und Design -

Must-See Exhibitions to Welcome You Back to London's Galleries Tabish Khan 27 April 2021

Londonist Must-See Exhibitions To Welcome You Back To London's Galleries Tabish Khan 27 April 2021 Must-See Exhibitions To Welcome You Back To London's Galleries Welcome to our pick of the best exhibitions to see right now in London's galleries. Due to social distancing, advance booking is required for many of these. Lucy Sparrow: Bourdon Street Chemist at Lyndsey Ingram, Mayfair. Until 8 May, free. Image: Courtesy of Lucy Emms/Lyndsey Ingram/sewyoursoul National Felt Service: The Queen of Felt is back, and this time Lucy Sparrow has created an entire pharmacy. Pop in and buy soft, cuddly versions of Lemsip, Xanax, and de rigueur antiseptic wipes. The attention to detail is superb — and will bring a smile to any visitor's face. We prescribe this as the perfect antidote to the year we've just had. Rebecca Manson: Dry Agonies of a Baffled Lust at Josh Lilley, Fitzrovia. Until 22 May, free. Image: Courtesy Josh Lilley. Leaf At First Sight: It's as if an explosion of leaves caught up in the wind has been frozen in time. These ceramic sculptures by Rebecca Manson are so lifelike, I hold my breath as I take a closer look — lest my exhalation disturbs it. Other leaves wrap around a rake, while sunflowers sprout in these spectacularly crafted works, whose level of detail is leaf mind-blowing. Sensing the Unseen: Step into Gossaert's 'Adoration' at The National Gallery, Room 1. 17 May - 13 June, free. Image: The National Gallery, London Step Into A Painting: Ever stood in front of a painting and wished you could step inside? The National Gallery invites us to do just that, with Jan Gossaert's The Adoration of the Kings. -

Listed Exhibitions (PDF)

G A G O S I A N G A L L E R Y Anish Kapoor Biography Born in 1954, Mumbai, India. Lives and works in London, England. Education: 1973–1977 Hornsey College of Art, London, England. 1977–1978 Chelsea School of Art, London, England. Solo Exhibitions: 2016 Anish Kapoor. Gagosian Gallery, Hong Kong, China. Anish Kapoor: Today You Will Be In Paradise. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, Milan, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Museo Universitario Arte Contemporáneo, Mexico City, Mexico. 2015 Descension. Galleria Continua, San Gimignano, Italy. Anish Kapoor. Regen Projects, Los Angeles, CA. Kapoor Versailles. Gardens at the Palace of Versailles, Versailles, France. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, Brussels, Belgium. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Prints from the Collection of Jordan D. Schnitzer. Portland Art Museum, Portland, OR. Anish Kapoor chez Le Corbusier. Couvent de La Tourette, Eveux, France. Anish Kapoor: My Red Homeland. Jewish Museum and Tolerance Centre, Moscow, Russia. 2013 Anish Kapoor in Instanbul. Sakıp Sabancı Museum, Istanbul, Turkey. Anish Kapoor Retrospective. Martin Gropius Bau, Berlin, Germany 2012 Anish Kapoor. Museum of Contemporary Art, Sydney, Australia. Anish Kapoor. Gladstone Gallery, New York, NY. Anish Kapoor. Leeum – Samsung Museum of Art, Seoul, Korea. Anish Kapoor, Solo Exhibition. PinchukArtCentre, Kiev, Ukraine. Anish Kapoor. Lisson Gallery, London, England. Flashback: Anish Kapoor. Longside Gallery, Yorkshire Sculpture Park, West Bretton, England. Anish Kapoor. De Pont Foundation for Contemporary Art, Tilburg, Netherlands. 2011 Anish Kapoor: Turning the Wold Upside Down. Kensington Gardens, London, England. Anish Kapoor: Flashback. Nottingham Castle Museum, Nottingham, England. -

Press Release Anish Kapoor

Press Release Anish Kapoor 15 May – 22 June 2019 27 Bell Street, London Opening: 14 May, 6 – 8pm Anish Kapoor returns for his seventeenth exhibition at Lisson Gallery with a new body of work that brings together two fundamental directions of his practice: his iconic and formal geometric languages as explored in stone, in symbiosis with the entropic drive of works enacted in silicone, oil on canvas and in welded steel. Though rarely exhibited until recently, painting has been an integral part of Kapoor’s pursuit for the last 40 years. Far from an anomaly, Kapoor’s works on canvas relate closely to his sculpture, both in their oscillation between two and three dimensions, as well as their shared existence at the threshold between form and formlessness. This formlessness is at its most visceral and abject here in a series of relief works. The thin gauze stretched across their surface, barely containing the interior that presses against it. Their surface, seeped in the blooming impressions of red and black paint, signals the turbulence and chaos of a state of immanent breach beneath. Alongside these are radical new gestural paintings; on the edge of figuration, they seem to depict swollen and fecund organs that ooze and leak from their dark interiors. Elsewhere an ovoid steel orifice, engulfed by a web of welded metallic shards, encapsulates the brutal eroticism of the works in the show. However, this is no easy seduction. Kapoor’s new works do not present us with a symbolised sensuality, rather it is in the ineffable dark voids of these generative forms that the artist creates a space we might intuit an as yet unknown known. -

Press Release

For Immediate Release. Tony Cragg February 1 – March 10, 2012 Opening reception: Wednesday, February 1st, 6-8 pm. Marian Goodman Gallery is delighted to present an exhibition of new sculpture by Tony Cragg opening on Wednesday, February 1st, and continuing through Saturday, March 10th. The exhibition will feature recent sculptures in bronze, corten steel, wood, cast iron, and stone. Concurrently, and accompanying the gallery presentation, a group of large scale works will be exhibited at The Sculpture Garden at 590 Madison Avenue (entrance at 56th Street). The Sculpture Garden is open to the public daily from 8 am to 10 pm. Tony Cragg is one of the most distinguished contemporary sculptors working today. During the past year, there have been several important solo exhibitions of his work worldwide: Seeing Things at The Nasher Sculpture Center, Dallas; Figure In/ Figure Out at The Louvre, Paris; Museum Küppersmühle für Moderne Kunst, Duisburg, Germany; Tony Cragg in 4 D from Flux to Stability at The International Gallery of Modern Art, Venice; It is, Isn’t It at the Church of San Cristoforo, Lucca, Italy; and Tony Cragg: Sculptures and Drawings at The Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art, Edinburgh. Cragg’s work developed within the context of diverse influences including early experiences in a scientific laboratory; English landscape and time-based art, a precursor to the presenting of found objects and fragments that characterized early performative work; and Minimalist sculpture, an antecedent to the stack, additive and accumulation works of the mid- seventies. Cragg has widened the boundaries of sculpture with a dynamic and investigative approach to materials, to images, and objects in the physical world, and an early use of found industrial objects and fragments. -

Richard Wentworth Samoa, 1947 Vive Y Trabaja En Londres, UK

CV Richard Wentworth Samoa, 1947 Vive y trabaja en Londres, UK Educación 2009/11 Profesor de escultura, Royal College of Art, Londres, UK 2002/10 Ruskin Master of Drawing, Ruskin School of Art, Oxford, UK 2001 Beca en San Francisco School of Art, San Francisco, CA, USA 1971/87 Tutor, Goldsmith's College, University of London, Londres, UK 1967 Trabajó para Henry Moore, UK 1966/70 Royal College of Art, London, UK Exposiciones individuales (selección) 2020 There’s no knowing, Blind Alley projects, Fort Worth, Texas, US 2019 Lecciones Aprendidas, NoguerasBlanchard, Madrid, ES School Prints 2019, The Hepworth Wakefield, UK 2017 Concertina, Arebyte Gallery, Londres, UK Richard Wentworth at Maison Alaïa, Galerie Azzedine Alaïa, París, FR Richard Wentworth: Paying A Visit, Nogueras Blanchard, Barcelona, ES Now and Then, Peter Freeman Inc., New York, USA 2015 False Ceiling, Museo de arte de Indianápolis, USA Bold Tendencies, Peckham, Londres, UK 2014 Motes to self, Peter Freeman Inc., New York, NY, USA 2013 A room full of lovers, Lisson Gallery, Londres, UK Black Maria (en colaboración con Gruppe), Kings Cross, Londres, UK 2012 Galeria Nicoletta Rusconi (con Alessandra Spranzi), Milán, IT Galerie Nelson Freeman, Art 43 Basel, Basel, CHE 2011 Richard Wentworth, Galerie Nelson Freeman, París, FR Richard Wentworth, Peter Freeman Inc., París, FR Richard Wentworth: Sidelines, Museu da Farmacia, Experimenta Design, Lisboa, PT 2010 Three Guesses, Whitechapel Gallery, Londres, UK Richard Wentworth, Peter Freeman Inc., New York, NY, USA 2009 Scrape/Scratch/Dig,