Analyzing the Linguistic Landscape of Japantown and Koreatown in Manhattan, New York

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Confronting Sa-I-Gu: Twenty Years After the Los Angeles Riots

【특집】 Confronting Sa-i-gu: Twenty Years after the Los Angeles Riots Edward Taehan Chang (the Young Oak Kim Center for Korean American Studies) Twenty years ago on April 29, Los Angeles erupted and Koreatown cried as it burned. For six-days, the LAPD was missing in action as rioting, looting, burning, and killing devastated the city. The “not guilty” Rodney King verdict ignited anger and frustration felt by South Los Angeles residents who suffered from years of neglect, despair, hopelessness, injustice, and oppression.1) In the Korean American community, the Los Angeles riot is remembered as Sa-i-gu (April 29 in Korean). Korean Americans suffered disproportionately high economic losses as 2,280 Korean American businesses were looted or burned with $400 million in property damages.2) Without any political clout and power in the city, Koreatown was unprotected and left to burn since it was not a priority for city politicians and 1) Rodney King was found dead in his own swimming pool on June 17, 2012, shortly after publishing his autobiography The Riot Within: My Journey from Rebellion to Redemption Learning How We Can All Get Along, in April 2012. 2) Korea Daily Los Angeles, May 11, 1992. 2 Edward Taehan Chang the LAPD. For the Korean American community, Sa-i-gu is known as its most important historical event, a “turning point,” “watershed event,” or “wake-up call.” Sa-i-gu profoundly altered the Korean American discourse, igniting debates and dialogue in search of new directions.3) The riot served as a catalyst to critically examine what it meant to be Korean American in relation to multicultural politics and race, economics and ideology. -

Distant Islands: the Japanese American Community in New York City [Review Of: D.H

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Distant Islands: The Japanese American Community In New York City [Review of: D.H. Inouye (2018) Distant Islands : the Japanese American community in New York City, 1876-1930s] Sooudi, O. Publication date 2019 Document Version Final published version Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Sooudi, O. (Author). (2019). Distant Islands: The Japanese American Community In New York City: [Review of: D.H. Inouye (2018) Distant Islands : the Japanese American community in New York City, 1876-1930s]. Web publication/site, The Gotham Center for New York City History. https://www.gothamcenter.org/blog/distant-islands-the-japanese-american- community-in-new-york-city General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:27 Sep 2021 Distant Islands: The Japanese American Community in New York City — The Gotham Center for New York City History THE GOTHAM CENTER FOR NEW YORK CITY HISTORY Distant Islands: The Japanese American Community In New York City July 30, 2019 · Gilded Age, Progressive Era, Reviews, Race & Ethnicity Reviewed by Olga Souudi Daniel H. -

From an Ethnic Island to a Transnational Bubble: a Reflection on Korean Americans in Los Angeles

Asian and Asian American Studies Faculty Works Asian and Asian American Studies 2012 From an Ethnic Island to a Transnational Bubble: A Reflection on Korean Americans in Los Angeles Edward J.W. Park Loyola Marymount University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lmu.edu/aaas_fac Part of the East Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Edward J.W. Park (2012) From an Ethnic Island to a Transnational Bubble: A Reflection on orK ean Americans in Los Angeles, Amerasia Journal, 38:1, 43-47. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Asian and Asian American Studies at Digital Commons @ Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. It has been accepted for inclusion in Asian and Asian American Studies Faculty Works by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons@Loyola Marymount University and Loyola Law School. For more information, please contact [email protected]. From an Ethnic Island to a Transnational Bubble Transnational a to Island an Ethnic From So much more could be said in reflecting on Sa-I-Gu. My main goal in this brief essay has simply been to limn the ways in which the devastating fires of Sa-I-Gu have produced a loamy and fecund soil for personal discovery, community organizing, political mobilization, and, ultimately, a remaking of what it means to be Korean and Asian in the United States. From an Ethnic Island to a Transnational Bubble: A Reflection on Korean Americans in Los Angeles Edward J.W. Park EDWARD J.W. PARK is director and professor of Asian Pacific American Studies at Loyola Marymount University in Los Angeles. -

CURRICULUM VITAE Min ZHOU, Ph.D

CURRICULUM VITAE Min ZHOU, Ph.D. ADDRESS Department of Sociology, UCLA 264 Haines Hall, 375 Portola Plaza, Box 951551 Los Angeles, CA 90095-1551 U.S.A. Office Phone: +1 (310) 825-3532 Email: [email protected]; home page: https://soc.ucla.edu/faculty/Zhou-Min EDUCATION May 1989 Doctor of Philosophy in Sociology, State University of New York (SUNY) at Albany May 1988 Certificate of Graduate Study in Urban Policy, SUNY-Albany December 1985 Master of Arts in Sociology, SUNY-Albany January 1982 Bachelor of Arts in English, Sun Yat-sen University (SYSU), China PHD DISSERTATION The Enclave Economy and Immigrant Incorporation in New York City’s Chinatown. UMI Dissertation Information Services, 1989. Advisor: John R. Logan, SUNY-Albany • Winner of the 1989 President’s Distinguished Doctoral Dissertation Award, SUNY-Albany PROFESSIONAL CAREER Current Positions • Distinguished Professor of Sociology and Asian American Studies, UCLA (since July 2021) • Walter and Shirley Wang Endowed Chair in U.S.-China Relations and Communications, UCLA (since 2009) • Director, UCLA Asia Pacific Center (since November 1, 2016) July 2000 to June 2021 • Professor of Sociology and Asian American Studies, UCLA • Founding Chair, Asian American Studies Department, UCLA (2004-2005; Chair of Asian American Studies Interdepartmental Degree Program (2001-2004) July 2013 to June 2016 • Tan Lark Sye Chair Professor of Sociology & Head of Division of Sociology, School of Humanities and Social Sciences, Nanyang Technological University (NTU), Singapore • Director, Chinese Heritage Centre (CHC), NTU, Singapore July 1994 to June 2000 Assistant to Associate Professor with tenure, Department of Sociology & Asian American Studies Interdepartmental Degree Program, UCLA August 1990 to July 1994 Assistant Professor of Sociology, Louisiana State University, Baton Rouge M. -

Japantown PDX

Portland State University PDXScholar University Honors Theses University Honors College 3-1-2019 Japantown PDX Euri Kashiwagi Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/honorstheses Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Kashiwagi, Euri, "Japantown PDX" (2019). University Honors Theses. Paper 755. https://doi.org/10.15760/honors.772 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in University Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. Euri Kashiwagi March 2019 Table of Contents 1 The History 3 The Audience 4 Color & Type 6 Logo 8 Logo Variations 10 Patterns 12 Deliverables 14 Posters 16 Pamphlet 18 Space Design 20 Business Card / Letterhead 22 Stickers / Website 24 Instagram / Facebook 26 Thank You Hand drawn map of the first Japantown (Little Tokyo) The History HISTORY apantown was established as a Japantown was more of a community, not Jcommunity for Japanese immigrants a tourist destination. As people came into looking for a job in Portland from 1890 to the area, Japantown started to establish as a 1941. There was an increase with the amount community, helping each other out through of hotels and restaurants in the community establishing venues that will support the as the Japanese population grew in the members in surviving America. Mikado 1890s. Many immigrants came in as laborers Hotel and Bathhouse, located in current from Japan, searching for a way to gain Northwest Everett and 3rd Avenue, provided money. -

Profile of New York City's Korean Americans

Profile of New York City’s Korean Americans Introduction Using data from 2006-2010 and 2011-2015 American Community Survey (ACS) Selected Population Tables and the 2010 U.S. census, this profile outlines characteristics and trends among New York City’s Korean American population.1 It presents statistics on population size and changes, immigration, citizenship status, educational attainment, English ability, income, poverty, health insurance and housing. Comparisons with New York City’s general population are provided for context. New York City’s Korean population was the third largest Asian ethnic group, behind Chinese and Indians. Relative to all residents, Koreans in New York City were more likely to be: working-age adults, Figure 1: Korean Population by Borough better educated, Population limited English proficient, From 2010 to 2015, the Korean alone or in combination living in poverty if an adult, and population in New York City decreased slightly by 0.2 renting. percent from 98,402 to 98,158 – compared to the city’s Facts on Korean Population in New York City overall 4 percent increase and the 13 percent growth of Alone or in-Combination Population 98,158 Percent Change from 2010 to 2015 -0.2% the total Asian population. The Korean alone population Immigration and Citizenship decreased by 1.5 percent from 93,131 in 2010 to 91,729 Percent of Population Foreign Born 70% in 2015. Percent of Foreign Born Who are Citizens 48% New York City was home to 67 percent of New York Educational Attainment for Adults Age 25 or Older State’s Korean residents. -

Korean American Creations and Discontents: Korean American Cultural Productions, Los Angeles, and Post-1992

Korean American Creations and Discontents: Korean American Cultural Productions, Los Angeles, and Post-1992 A Dissertation SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Michelle Chang IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Josephine Lee, Co-Advisor Elliott Powell, Co-Advisor December 2020 © Michelle Chang 2020 i Acknowledgements As I write the last section of my dissertation, I find myself at a loss for words. 55,000+ words later and my writing fails me. While the dissertation itself is an overwhelming feat, this acknowledgements section feels equally heavy. Expressing my gratitude and thanks for every person who has made this possiBle feels quite impossiBle. And as someone who once detested both school and writing, there’s a lot of people I am thankful for. It is a fact that I could not completed a PhD, let alone a dissertation, on my own. Graduate school wears you down, and especially one framed By the 2016 presidential election and 2020 uprisings, rise of white supremacy, and a gloBal pandemic, graduate school is really hard and writing is the last thing you want to do. While I’ve spent days going through mental lists of people and groups who’ve helped me, this is not a complete list and my sincere apologies to anyone I’ve forgotten. First and foremost, this dissertation would not be where it is today without the guidance and support of my advisors Jo Lee and Elliott Powell. The hours of advice and words of wisdom I received from you both not only shaped my project and affirmed its direction, but they also reminded me of the realistic expectations we should have for ourselves. -

Little Saigon, Japantown, Chinatown – International District Vision 2030

Little Saigon, Japantown, Chinatown – International District Vision 2030 A Community Response to the Preliminary Recommendations of the “South Downtown Livable Communities Study” June 2006 Thomas Im Edgar Yang Don Mar Tuck Eng Paul Lee Alan Cornell Paul Mar Stella Chao Sue Taoka Fen Hsiao Joyce Pisnanont Mike Olson Tomio Moriguchi Ken Katahira Virgil Domaoan Joe Nabberfeld 1 Little Saigon, Japantown, and Chinatown/International District Vision 2030 Executive Summary The City of Seattle initiated the Livable South Downtown study in 2005 as an extension of the Center City Initiative, a plan to increase housing capacity and economic activity in the downtown core. After several meetings with twenty-five South Downtown community stakeholders, the City released a draft report in January 2006, outlining land use and rezoning recommendations. An alliance of Little Saigon, Japantown, and Chinatown-International District stakeholders met to discuss the report and agreed that the City needed to broaden its scope of work, as well as its vision for the neighborhood. The community went through a visioning process and produced a narrative document called Vision 2030 (in reference to the year 2030). This vision builds on the recommendations and values of the 1998 Chinatown-International District Neighborhood Plan. This vision document describes the Little Saigon, Japantown, Chinatown-International District in the year 2030 as a healthy, vital, and vibrant community supported by safe, pedestrian-friendly streets, new and improved open spaces, and a diverse array of retail stores that support the variety of people who live in the area. Vision 2030 also advocates for a balanced mix of neighborhood housing options, ranging from condos for empty nesters to affordable family housing units. -

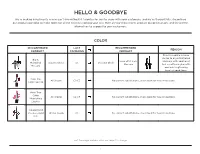

Hello & Goodbye

HELLO & GOODBYE We’re making investments in new can’t-live-without-it favorites for you to share with your customers, and we’ve thoughtfully streamlined our product portfolio to make room for all the newness coming your way. Here are our most recent product discontinuations and the perfect alternatives to suggest to your customers. COLOR DISCONTINUED LAST RECOMMENDED REASON PRODUCT CAMPAIGN PRODUCT Gives incredible volume, similar to Big & Multiplied Big & Love at 1st Lash Mascara, with additional Multiplied Blackest Black C5 Blackest Black Mascara lash conditioning benefits Mascara and lash lengthening heart-shaped fibers Avon True All Shades C2-C5 No current substitutions, check back for new innovations Color Lipstick Avon True Color All Shades C2-C5 No current substitutions, check back for new innovations Nourishing Lipstick Superextend Precise Liquid Brown Suede C5 No current substitutions, check back for new innovations Pen Last Campaign available dates are subject to change. 1 COLOR DISCONTINUED LAST RECOMMENDED REASON PRODUCT CAMPAIGN PRODUCT N20 Neutral Light The Face Shop Ink Lasting W20 Ivory C6 No current substitutions, check back for new innovations Foundation Slim Fit N70 Deep Living Coral The Face Shop Pure Red Ink Serum C5 No current substitutions, check back for new innovations Lip Tint Hug Red Tempting Pink The Face Shop Rogue All Shades C5 No current substitutions, check back for new innovations Satin Moisture Lipstick The Face Shop Rogue Powder All Shades C5 No current substitutions, check back for new innovations Matte Lipstick The Face Shop Flat Velvet Pink Moment C7 No current substitutions, check back for new innovations Lipstick Last Campaign available dates are subject to change. -

Strategic Marketing Planning in South Korea Finnish Company Entering South Korean Beauty Market: Case Lu- Mene

Strategic Marketing Planning in South Korea Finnish company entering South Korean beauty market: Case Lu- mene LAB University of Applied Sciences Bachelor of Business Administration, International Business 2020 Iuliia Trofimova Abstract Author(s) Publication type Completion year Trofimova, Iuliia Thesis, UAS 2020 Number of pages 75 Title of the thesis Strategic Marketing Planning in South Korea Finnish company entering South Korean beauty market: Case Lumene Name of Degree Bachelor of Business Administration Name, title and organisation of the thesis supervisor Emmi Maijanen, Senior Lecturer, Business Administration Name, title and organisation of the client Abstract The thesis focuses on the development of a strategic marketing plan for Lumene Oy to enter the beauty market in South Korea. The research objectives aim to investigate the phenomenon of the strategic marketing planning process according to theoretical knowledge and practical constituent on the basis of Lumene company. In 2014, the company had an attempt to enter the South Korean market, however, there is no rele- vant data associated with it now. The beauty industry in South Korea is diverse, it gives brands new opportunities for business expansion. Lumene already has experi- ence of entering the global market and gains success in such countries as the USA and Russia. The thesis includes an analysis of the country’s marketing environment with the purpose to illustrate the main differences between South Korea and Finland and describe factors of influence towards strategic decisions. The theoretical framework explains the concepts of the marketing environment itself and strategic marketing planning. The section includes visualization related to the strategic process for the comprehensible picture. -

Seattle Report

EPA: CARE Level I Final Report International District CARE Project Community elder shares her perspectives at the first CARE partner meeting, 2005 Better Housing, Happier Lives, Stronger Communities _____________________________________________________________________________________________ 606 Maynard Avenue South, Suite 105 . Seattle WA 98104 . Tel (206) 623-5132 . Fax: (206) 623-3479 . www.idhousingalliance.org Grantee: International District Housing Alliance Project location: Seattle’s Chinatown-International District, Seattle, WA – King County Project title: International District CARE Project Grant period: October 1, 2005 to September 30, 2007 Project Manager: Joyce Pisnanont EPA Project Officer: Sally Hanft Personal Reflection: Reflecting on the past two years of the ID CARE project, it is evident that our community has had many wonderful successes, as well as a fair share of challenges. Our successes included a tremendous amount of culturally relevant outreach and education and the development of a strong core of community leadership amongst limited English speaking populations. Our greatest challenges were maintaining the momentum of the work in the face of organizational restructuring (in year 2) and growing anti-immigrant sentiments nationwide that inhibited civic participation on the part of our immigrant youth and elders. Perhaps our greatest area for improvement is the partnership development piece. Since 2005, IDHA has successfully garnered many new partnerships, but needs to strengthen our project advisory committee so as to be truly representative of the multiple community stakeholders that are essential for driving the project forward. This became most clear during our recent CARE National Training in Atlanta, GA. In listening to the successes and challenges of other CARE grantees, it became evident where the ID community’s strengths lay, and where we could have done many things differently. -

DEEP DIVE: Have Had a Growing Influence on the Global Beauty Market in Recent Years, Leading to a K-Beauty Trend

NOVEMBER 16, 2016 Korean beauty brands have seen strong growth in sales volume, with eXports reaching US$2.45 billion in 2015. Korean brands DEEP DIVE: have had a growing influence on the global beauty market in recent years, leading to a K-Beauty trend. Korean In this report, we eXamine the factors that underpin the successful ascent of Korean beauty, with a focus on the product, process and technology innovations they have brought Innovation to the market. Here are our key takeaways. 1) Korean beauty brands have adopted a “fast fashion” product development cycle and gained recognition for in Beauty innovative formulas, ingredients, manufacturing processes and packaging. However, the sophisticated and demanding customers in the local Korean market have also been one of the major drivers. 2) Korean beauty brands have embraced the digital transformation age and have taken advantage of the cultural influence of the Korean wave to come up with innovative marketing strategies that have driven growth. 3) Korean beauty brands were also fast to adopt in-store technologies, some of which are on par with other technology developed by international beauty brands, while others are ahead of the international market. DEBORAH WEINSWIG 4) A number of Korean beauty startups have emerged that Managing Director, Fung Global Retail & Technology have brought Korean beauty products overseas with e- [email protected] commerce, or created innovative beauty products with US: 646 .839.7017 HK: 852.6119.1779 the latest technologies. CN: 86.186.1420.3016 DEBORAH WEINSWIG, MANAGING DIRECTOR, FUNG GLOBAL RETAIL & TECHNOLOGY 1 [email protected] US: 917.655.6790 HK: 852.6119.1779 CN: 86.186.1420.3016 Copyright © 2016 The Fung Group.