Animal Acts CRITICAL PERFORMANCES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Compilation and Analysis of Food Plants Utilization of Sri Lankan Butterfly Larvae (Papilionoidea)

MAJOR ARTICLE TAPROBANICA, ISSN 1800–427X. August, 2014. Vol. 06, No. 02: pp. 110–131, pls. 12, 13. © Research Center for Climate Change, University of Indonesia, Depok, Indonesia & Taprobanica Private Limited, Homagama, Sri Lanka http://www.sljol.info/index.php/tapro A COMPILATION AND ANALYSIS OF FOOD PLANTS UTILIZATION OF SRI LANKAN BUTTERFLY LARVAE (PAPILIONOIDEA) Section Editors: Jeffrey Miller & James L. Reveal Submitted: 08 Dec. 2013, Accepted: 15 Mar. 2014 H. D. Jayasinghe1,2, S. S. Rajapaksha1, C. de Alwis1 1Butterfly Conservation Society of Sri Lanka, 762/A, Yatihena, Malwana, Sri Lanka 2 E-mail: [email protected] Abstract Larval food plants (LFPs) of Sri Lankan butterflies are poorly documented in the historical literature and there is a great need to identify LFPs in conservation perspectives. Therefore, the current study was designed and carried out during the past decade. A list of LFPs for 207 butterfly species (Super family Papilionoidea) of Sri Lanka is presented based on local studies and includes 785 plant-butterfly combinations and 480 plant species. Many of these combinations are reported for the first time in Sri Lanka. The impact of introducing new plants on the dynamics of abundance and distribution of butterflies, the possibility of butterflies being pests on crops, and observations of LFPs of rare butterfly species, are discussed. This information is crucial for the conservation management of the butterfly fauna in Sri Lanka. Key words: conservation, crops, larval food plants (LFPs), pests, plant-butterfly combination. Introduction Butterflies go through complete metamorphosis 1949). As all herbivorous insects show some and have two stages of food consumtion. -

Guide to the Betty J. Meggers and Clifford Evans Papers

Guide to the Betty J. Meggers and Clifford Evans papers Tyler Stump and Adam Fielding Funding for the processing of this collection was provided by the Smithsonian Institution's Collections Care and Preservation Fund. December 2015 National Anthropological Archives Museum Support Center 4210 Silver Hill Road Suitland, Maryland 20746 [email protected] http://www.anthropology.si.edu/naa/ Table of Contents Collection Overview ........................................................................................................ 1 Administrative Information .............................................................................................. 1 Biographical / Historical.................................................................................................... 2 Scope and Contents........................................................................................................ 5 Arrangement..................................................................................................................... 5 Bibliography...................................................................................................................... 6 Names and Subjects ...................................................................................................... 6 Container Listing ............................................................................................................. 8 Series 1: Personal, 1893-2012................................................................................. 8 Series 2: Writings, 1944-2011............................................................................... -

Appendix A: Common and Scientific Names for Fish and Wildlife Species Found in Idaho

APPENDIX A: COMMON AND SCIENTIFIC NAMES FOR FISH AND WILDLIFE SPECIES FOUND IN IDAHO. How to Read the Lists. Within these lists, species are listed phylogenetically by class. In cases where phylogeny is incompletely understood, taxonomic units are arranged alphabetically. Listed below are definitions for interpreting NatureServe conservation status ranks (GRanks and SRanks). These ranks reflect an assessment of the condition of the species rangewide (GRank) and statewide (SRank). Rangewide ranks are assigned by NatureServe and statewide ranks are assigned by the Idaho Conservation Data Center. GX or SX Presumed extinct or extirpated: not located despite intensive searches and virtually no likelihood of rediscovery. GH or SH Possibly extinct or extirpated (historical): historically occurred, but may be rediscovered. Its presence may not have been verified in the past 20–40 years. A species could become SH without such a 20–40 year delay if the only known occurrences in the state were destroyed or if it had been extensively and unsuccessfully looked for. The SH rank is reserved for species for which some effort has been made to relocate occurrences, rather than simply using this status for all elements not known from verified extant occurrences. G1 or S1 Critically imperiled: at high risk because of extreme rarity (often 5 or fewer occurrences), rapidly declining numbers, or other factors that make it particularly vulnerable to rangewide extinction or extirpation. G2 or S2 Imperiled: at risk because of restricted range, few populations (often 20 or fewer), rapidly declining numbers, or other factors that make it vulnerable to rangewide extinction or extirpation. G3 or S3 Vulnerable: at moderate risk because of restricted range, relatively few populations (often 80 or fewer), recent and widespread declines, or other factors that make it vulnerable to rangewide extinction or extirpation. -

Cosmos: a Spacetime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based On

Cosmos: A SpaceTime Odyssey (2014) Episode Scripts Based on Cosmos: A Personal Voyage by Carl Sagan, Ann Druyan & Steven Soter Directed by Brannon Braga, Bill Pope & Ann Druyan Presented by Neil deGrasse Tyson Composer(s) Alan Silvestri Country of origin United States Original language(s) English No. of episodes 13 (List of episodes) 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way 2 - Some of the Things That Molecules Do 3 - When Knowledge Conquered Fear 4 - A Sky Full of Ghosts 5 - Hiding In The Light 6 - Deeper, Deeper, Deeper Still 7 - The Clean Room 8 - Sisters of the Sun 9 - The Lost Worlds of Planet Earth 10 - The Electric Boy 11 - The Immortals 12 - The World Set Free 13 - Unafraid Of The Dark 1 - Standing Up in the Milky Way The cosmos is all there is, or ever was, or ever will be. Come with me. A generation ago, the astronomer Carl Sagan stood here and launched hundreds of millions of us on a great adventure: the exploration of the universe revealed by science. It's time to get going again. We're about to begin a journey that will take us from the infinitesimal to the infinite, from the dawn of time to the distant future. We'll explore galaxies and suns and worlds, surf the gravity waves of space-time, encounter beings that live in fire and ice, explore the planets of stars that never die, discover atoms as massive as suns and universes smaller than atoms. Cosmos is also a story about us. It's the saga of how wandering bands of hunters and gatherers found their way to the stars, one adventure with many heroes. -

American Lady, American Painted Lady, Vanessa Virginiensis (Drury) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Nymphalinae)1 Donald W

EENY 449 American Lady, American Painted Lady, Vanessa virginiensis (Drury) (Insecta: Lepidoptera: Nymphalidae: Nymphalinae)1 Donald W. Hall2 The Featured Creatures collection provides in-depth profiles of insects, nematodes, arachnids, and other organisms relevant to Florida. These profiles are intended for the use of interested laypersons with some knowledge of biology as well as academic audiences. Introduction Vanessa virginiensis (Drury) has been known by a number of common names (Cech and Tudor 2005, Miller 1992) including American lady, American painted lady, painted beauty, and Hunter’s butterfly. It will be referred to here as the American lady in accord with the Checklist of North American Butterflies Occurring North of Mexico (NABA 2004). Although the adult American lady is an attractive butterfly, it is probably best known among naturalists for the characteristic nests made by its caterpillars. Figure 1. Adult American lady, Vanessa virginiensis (Drury), with dorsal view of wings. Credits: Don Hall, UF/IFAS Distribution The American lady occurs from southern Canada through- out the United States and southward to northern South America and is seen occasionally in Europe, Hawaii, and the larger Caribbean islands (Scott 1986; Opler and Krizek 1984; Cech and Tudor 2005). 1. This document is EENY 449, one of a series of the Entomology and Nematology Department, UF/IFAS Extension. Original publication date June 2009. Revised February 2018 and February 2021. Visit the EDIS website at https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu for the currently supported version of this publication. This document is also available on the Featured Creatures website at http://entomology.ifas.ufl.edu/creatures. -

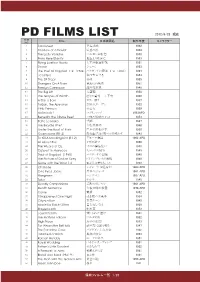

Pd Films List 0824

PD FILMS LIST 2012/8/23 現在 FILM Title 日本映画名 制作年度 キャラクター NO 1 Sabouteur 逃走迷路 1942 2 Shadow of a Doubt 疑惑の影 1943 3 The Lady Vanishe バルカン超特急 1938 4 From Here Etanity 地上より永遠に 1953 5 Flying Leather Necks 太平洋航空作戦 1951 6 Shane シェーン 1953 7 The Thief Of Bagdad 1・2 (1924) バクダッドの盗賊 1・2 (1924) 1924 8 I Confess 私は告白する 1953 9 The 39 Steps 39夜 1935 10 Strangers On A Train 見知らぬ乗客 1951 11 Foreign Correspon 海外特派員 1940 12 The Big Lift 大空輸 1950 13 The Grapes of Wirath 怒りの葡萄 上下有 1940 14 A Star Is Born スター誕生 1937 15 Tarzan, the Ape Man 類猿人ターザン 1932 16 Little Princess 小公女 1939 17 Mclintock! マクリントック 1963APD 18 Beneath the 12Mile Reef 12哩の暗礁の下に 1953 19 PePe Le Moko 望郷 1937 20 The Bicycle Thief 自転車泥棒 1948 21 Under The Roof of Paris 巴里の屋根の根 下 1930 22 Ossenssione (R1.2) 郵便配達は2度ベルを鳴らす 1943 23 To Kill A Mockingbird (R1.2) アラバマ物語 1962 APD 24 All About Eve イヴの総て 1950 25 The Wizard of Oz オズの魔法使い 1939 26 Outpost in Morocco モロッコの城塞 1949 27 Thief of Bagdad (1940) バクダッドの盗賊 1940 28 The Picture of Dorian Grey ドリアングレイの肖像 1949 29 Gone with the Wind 1.2 風と共に去りぬ 1.2 1939 30 Charade シャレード(2種有り) 1963 APD 31 One Eyed Jacks 片目のジャック 1961 APD 32 Hangmen ハングマン 1987 APD 33 Tulsa タルサ 1949 34 Deadly Companions 荒野のガンマン 1961 APD 35 Death Sentence 午後10時の殺意 1974 APD 36 Carrie 黄昏 1952 37 It Happened One Night 或る夜の出来事 1934 38 Cityzen Ken 市民ケーン 1945 39 Made for Each Other 貴方なしでは 1939 40 Stagecoach 駅馬車 1952 41 Jeux Interdits 禁じられた遊び 1941 42 The Maltese Falcon マルタの鷹 1952 43 High Noon 真昼の決闘 1943 44 For Whom the Bell tolls 誰が為に鐘は鳴る 1947 45 The Paradine Case パラダイン夫人の恋 1942 46 I Married a Witch 奥様は魔女 -

Patterns of Diversity and Distribution of Butterflies in Heterogeneous Landscapes of the W Estern Ghats, India

595.2890954 P04 (CES) PATTERNS OF DIVERSITY AND DISTRIBUTION OF BUTTERFLIES IN HETEROGENEOUS LANDSCAPES OF THE W ESTERN GHATS, INDIA Geetha Nayak1, Subramanian, K.A2., M adhav Gadgil3 , Achar, K.P4., Acharya5, Anand Padhye6, Deviprasad7, Goplakrishna Bhatta8, Hemant Ghate9, M urugan10, Prakash Pandit11, ShajuThomas12 and W infred Thomas13 ENVIS TECHNICAL REPORT No.18 Centre for Ecological Sciences Indian Institute of Science Bangalore-560 012 Email: ceslib@ ces.iisc.ernet.in December 2004 Geetha Nayak1, Subramanian, K.A2., M adhav Gadgil3 Achar, K.P4., Acharya5, Anand Padhye6, Deviprasad7, Goplakrishna Bhatta8, Hemant Ghate9, M urugan10, Prakash Pandit11, Shaju Thomas12 and W infred Thomas13 1. Salim Ali School of Ecology, Pondicherry University, Pondicherry. 2. National Centre for Biological Sciences, GKVK Campus, Bangalore-65 3. Centre for Ecological Sciences, IISc, Bangalore 4. Mathrukripa, Thellar road, Karkala, Udupi- 5. BSGN, Nasik 6. Dept. of Zoology, Abasaheb Garware College, Pune 7. Nehru Memorial P.U. College, Aranthodu, Sullia 8. Dept. of Zoology, Bhandarkar College, Kuntapur 9. Dept. of Zoology, Modern College Pune 10. Dept. of Botany, University College, Trivandrum 11. Dept. of Zoology, A.V. Baliga College, Kumta 12. Dept. of Zoology, Nirmala College, Muvattupuzha 13. Dept. of Botany, American College, Madurai Abstract Eight localities in various parts of the W estern Ghats were surveyed for pattern of butterfly diversity, distribution and abundance. Each site had heterogeneous habitat matrices, which varied from natural habitats to modified habitats like plantations and agricultural fields. The sampling was done by the belt transects approximately 500m in length with 5 m on either side traversed in one hour in each habitat type. -

3515100105 Lp.Pdf

Irene Kletschke Klangbilder Beihefte zum Archiv für Musikwissenschaft -------------------------------------------- herausgegeben von Albrecht Riethmüller in Verbindung mit Reinhold Brinkmann †, Ludwig Finscher, Hans-Joachim Hinrichsen, Birgit Lodes und Wolfram Steinbeck Band 67 Irene Kletschke Klangbilder Walt Disneys „Fantasia“ (1940) Franz Steiner Verlag 2011 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Förderungs- und Beihilfefonds Wissenschaft der VG WORT Bibliografische Information der Deutschen National- bibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über <http://dnb.d-nb.de> abrufbar. ISBN 978-3-515-09828-1 Jede Verwertung des Werkes außerhalb der Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist unzulässig und strafbar. Dies gilt insbesondere für Übersetzung, Nachdruck, Mikroverfilmung oder vergleichbare Verfahren sowie für die Speicherung in Datenver- arbeitungsanlagen. © 2011 Franz Steiner Verlag, Stuttgart Gedruckt auf säurefreiem, alterungs beständigem Papier. Druck: Offsetdruck Bokor, Bad Tölz Printed in Germany Meiner Mutter INHALTSVERZEICHNIS DANKSAGUNG .................................................................................……… 9 EINLEITUNG .............................................................................................. 11 1. WALT DISNEY IM JAHR 1940 .............................................................. 17 1.1 Vom Toncartoon zum ersten abendfüllenden Zeichentrickfilm ........ 17 1.2 Disney als moralisches -

UNEP Frontiers 2016 Report: Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern

www.unep.org United Nations Environment Programme P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi 00100, Kenya Tel: +254-(0)20-762 1234 Fax: +254-(0)20-762 3927 Email: [email protected] web: www.unep.org UNEP FRONTIERS 978-92-807-3553-6 DEW/1973/NA 2016 REPORT Emerging Issues of Environmental Concern 2014 © 2016 United Nations Environment Programme ISBN: 978-92-807-3553-6 Job Number: DEW/1973/NA Disclaimer This publication may be reproduced in whole or in part and in any form for educational or non-profit services without special permission from the copyright holder, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. UNEP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication that uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or any other commercial purpose whatsoever without prior permission in writing from the United Nations Environment Programme. Applications for such permission, with a statement of the purpose and extent of the reproduction, should be addressed to the Director, DCPI, UNEP, P.O. Box 30552, Nairobi, 00100, Kenya. The designations employed and the presentation of material in this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of UNEP concerning the legal status of any country, territory or city or its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. For general guidance on matters relating to the use of maps in publications please go to: http://www.un.org/Depts/Cartographic/english/htmain.htm Mention of a commercial company or product in this publication does not imply endorsement by the United Nations Environment Programme. -

Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: C Biological Science Botany & Zology

Online ISSN : 2249-4626 Print ISSN : 0975-5896 DOI : 10.17406/GJSFR DiversityofButterflies RevisitingMelaninMetabolism InfluenceofHigh-FrequencyCurrents GeneticStructureofSitophilusZeamais VOLUME20ISSUE4VERSION1.0 Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: C Biological Science Botany & Zology Global Journal of Science Frontier Research: C Biological Science Botany & Zology Volume 20 Issue 4 (Ver. 1.0) Open Association of Research Society Global Journals Inc. © Global Journal of Science (A Delaware USA Incorporation with “Good Standing”; Reg. Number: 0423089) Frontier Research. 2020 . Sponsors:Open Association of Research Society Open Scientific Standards All rights reserved. This is a special issue published in version 1.0 Publisher’s Headquarters office of “Global Journal of Science Frontier Research.” By Global Journals Inc. Global Journals ® Headquarters All articles are open access articles distributed 945th Concord Streets, under “Global Journal of Science Frontier Research” Framingham Massachusetts Pin: 01701, Reading License, which permits restricted use. United States of America Entire contents are copyright by of “Global USA Toll Free: +001-888-839-7392 Journal of Science Frontier Research” unless USA Toll Free Fax: +001-888-839-7392 otherwise noted on specific articles. No part of this publication may be reproduced Offset Typesetting or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including G lobal Journals Incorporated photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without written 2nd, Lansdowne, Lansdowne Rd., Croydon-Surrey, permission. Pin: CR9 2ER, United Kingdom The opinions and statements made in this book are those of the authors concerned. Packaging & Continental Dispatching Ultraculture has not verified and neither confirms nor denies any of the foregoing and no warranty or fitness is implied. -

New York Wildflower Habitat Establishment Guide

Planting for Pollinators and Beneficial Insects New York Wildflower Habitat Establishment Guide January 2018 The Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation www.xerces.org American lady butterfly (Vanessa virginiensis) on purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea). Photo: Shawnna Clark, USDA NRCS Acknowledgements Development of these guidelines for New York was supported by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service, under Contribution Agreement number 68-2B29-14-220. Any opinions, findings, conclusions, or recommendations expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Additional support for the development of this guide was provided by Cascadian Farm, Ceres Trust, Cheerios, CS Fund, Disney Conservation Fund, The Dudley Foundation, Endangered Species Chocolate, LLC., General Mills, Häagen-Dazs, J.Crew, Madhava Natural Sweeteners, Nature Valley, Sarah K. de Coizart Article TENTH Perpetual Charitable Trust, Turner Foundation, Inc., The White Pine Fund, Whole Foods Market and its vendors, Whole Systems Foundation, and Xerces Society members. Authors Core content for this guide was written by Mace Vaughan, Eric Mäder, Jessa Kay Cruz, Jolie Goldenetz-Dollar, Kelly Gill, and Brianna Borders of the Xerces Society for Invertebrate Conservation. Updated content adapted for New York was written by Kelly Gill (Xerces Society). Please contact Kelly Gill ([email protected]) to improve this publication. The authors would like to thank the following collaborators with NRCS NY for assisting with the development and review of this guide: Kim Farrell, Shawnna Clark, Elizabeth Marks, and Shanna Shaw. Photographs We thank the photographers who generously allowed use of their images. -

Common Butterflies of the Chicago Region

Common Butterflies of the Chicago Region 1 Chicago Wilderness, USA The Field Museum, Illinois Butterfly Monitoring Network Photos by: John and Jane Balaban, Tom Peterson, Doug Taron Produced by: Rebecca Collings and John Balaban © The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 USA. [http://idtools.fieldmuseum.org] [[email protected]] version 1 (7/2013) VICEROY: line crossing through hind wing, smaller than a Monarch. Host plants: Willows (Salix). MONARCH: no line crossing through the hind wing, much larger and a stronger flier than a Viceroy. Host plants: Milkweeds (Asclepias). 1 Viceroy 2 Monarch - Male 3 Monarch - Female Limentis archippus Danaus plexippus Danaus plexippus BLACK SWALLOWTAIL: in addition to outer line of yellow dots, male has a strong inner line, and blue may be almost absent. Female with much weaker inner line of yellow with separate spot near tip of wing. Some blue on hind-wing, but does not extend up into hindwing above row of faint spots. Host Plants: Parsley Family (Api- 4 Black Swallowtail 5 Black Swallowtail 6 Black Swallowtail aceae). Papilio polyxenes Papilio polyxenes Papilio polyxenes EASTERN TIGER SWALLOW- TAIL: no inner line of yellow dots. No dot near tip. Lots of blue on hindwing, up into center of hind wing. No inner row of orange dots. Tiger stripes often still visible on female dark form. Host Plants: Black Cherry (Prunus serotina) and Tulip Tree (Lirioden- dron tulipifera). 7 Eastern Tiger Swallowtail 8 Eastern Tiger Swallowtail 9 Eastern Tiger Swallowtail Papilio glaucus Papilio glaucus Papilio glaucus RED SPOTTED PURPLE: no tails, no line of yellow spots. Blue-green iridescence depends on lighting.