Improvement of Stone Fruits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pru Nus Contains Many Species and Cultivars, Pru Nus Including Both Fruits and Woody Ornamentals

;J. N l\J d.000 A~ :J-6 '. AGRICULTURAL EXTENSION SERVICE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA • The genus Pru nus contains many species and cultivars, Pru nus including both fruits and woody ornamentals. The arboretum's Prunus maacki (Amur Cherry). This small tree has bright, emphasis is on the ornamental plants. brownish-yellow bark that flakes off in papery strips. It is par Prunus americana (American Plum). This small tree furnishes ticularly attractive in winter when the stems contrast with the fruits prized for making preserves and is also an ornamental. snow. The flowers and fruits are produced in drooping racemes In early May, the trees are covered with a "snowball" bloom similar to those of our native chokecherry. This plant is ex of white flowers. If these blooms escape the spring frosts, tremely hardy and well worth growing. there will be a crop of colorful fruits in the fall. The trees Prunus maritima (Beach Plum). This species is native to the sucker freely, and unless controlled, a thicket results. The A coastal plains from Maine to Virginia. It's a sprawling shrub merican Plum is excellent for conservation purposes, and the reaching a height of about 6 feet. It blooms early with small thickets are favorite refuges for birds and wildlife. white flowers. Our plants have shown varying degrees of die Prunus amygdalus (Almond). Several cultivars of almonds back and have been removed for this reason. including 'Halls' and 'Princess'-have been tested. Although Prunus 'Minnesota Purple.' This cultivar was named by the the plants survived and even flowered, each winter's dieback University of Minnesota in 1920. -

2021 BAREROOT WISH LIST PAGE 1 of 9

2021 BAREROOT WISH LIST PAGE 1 of 9 Customer Name: Order Contact Name: Customer Number: Contact Email: Telephone: Delivery Address: Postcode: Signature: Date: FRUIT TREES APPLE QTY ALMOND QTY Easy Care™ - Crimson Crisp™ cv. 'Co-op 39' A All-in-One™ Self-fertile Easy Care™ - Pixie Crunch™ cv. ‘Co-op 33’ A APRICOT QTY ‘Gala’ ‘Divinity’ ‘Golden Delicious’ ‘Moorpark’ ‘Granny Smith’ ‘Story’ ‘Jonathan’ ‘Trevatt’ Pink Lady™ CHERRY QTY ‘Red Delicious’ ‘Lapins’ Self-fertile ‘Red Fuji’ ‘Morello’ Sour cherry DWARF APPLE QTY Dwarf Easy Care™ - Crimson Crisp™ cv. ‘Co-op 39’ A Dwarf Easy Care™ - Pixie Crunch™ cv. ‘Co-op 33’ A Dwarf ‘Gala’ Dwarf ‘Golden Delicious’ ‘Minnie Royal’ A White, Low Chill Dwarf ‘Granny Smith’ ‘Royal Crimson’ A White, Low Chill Dwarf Pink Lady™ ‘Royal Lee’ White, Low Chill Dwarf ‘Red Fuji’ ‘Royal Rainier’ A White SPECIALTY APPLE QTY ‘Starkrimson’ Self-fertile ® Ballerina Columnar Apple - ‘Bolero’ A ‘Stella’ Self-fertile ® Ballerina Columnar Apple - ‘Flamenco’ A ‘Sunburst’ Self-fertile ® ® ® Ballerina Columnar Apple - ‘Polka’ A Trixzie Miniature Cherry Black Cherree Ballerina® Columnar Apple - ‘Waltz’ A Trixzie® Miniature Cherry White Cherree® Skinny® Columnar Apple - ‘Dita’ A CHESTNUT QTY Trixzie® Miniature Apple ‘Gala’ ‘Fleming’s Prolific’ Grafted Trixzie® Miniature Apple Pink Lady™ ‘Fleming’s Special’ Grafted Seedling Quarantine Restrictions: Subject to change by government authorities at any time. Minimum order quantities apply. Please read conditions of sale attached. All stock must be ordered in bundles *Eligibility of this plant as a registrable plant variety under Section 43(6) of the Plant Breeder’s Rights Act 1994 of five (excluding weepers). Broken bundles will incur a 20% surcharge. -

Plums (European)

AMERICAN MIRABELLE August 10 - 20 IMPERIAL EPINEUSE August 15 - 25 ‘American Mirabelle’ was developed in the US, Introduced to California from France in 1883 likely as an attempt to improve the eating from Clairac, where it was also known as quality of the famous ‘Mirabelle’ of France. “Clairac Mammoth”. Rarely grown there but Ironically, this was accomplished by crossing the particularly adapted to the Santa Clara Valley existing ‘Mirabelle’ wIth yet another French where it was once grown and dried into an import, the ‘Agen’ or ‘French’ plum. The name exceptionally large and high quality prune. ‘American’, a bow to Americans, ingenuity not Distinctive flavor as a fresh market plum. the origin of the variety’s parents. A unique MIRABELLE August 1 - 25 and luscious flavor unlike other ‘Mirabelles’. This is a class of plums we grow that include COE’S GOLDEN DROP September 5 - 20 ‘Mirabelle de Nancy, ‘Mirabelle de Metz’, and A veritable bag of sweet nectar when fully ripe. ‘Geneva Mirabelle’. All are small, cherry-sized Very rich, sweet flavor. The famous epicure fruits that many of our chef patrons purchase Edward Bunyard suggested that “at its ripest, it for dessert making and other culinary purposes. is drunk rather than eaten.” A real “juice MUIR BEAUTY August 10 - 20 oozer”. One of the very old European dessert ‘Muir Beauty’ is a relatively new prune plum plums. developed by the University of California, Davis. DAMSON August 15 – 25 It combines the sweetness of the old ‘French’ We grow several strains including ‘Blue Jam’ prune with a rich flavor that is unique to this and ‘Jam Session’. -

Plum Crazy: Rediscovering Our Lost Prunus Resources W.R

Plum Crazy: Rediscovering Our Lost Prunus Resources W.R. Okie1 U.S. Department of Agriculture–Agricultural Research Service, Southeastern Fruit and Tree Nut Research Laboratory, 21 Dunbar Road, Byron, GA 31008 Recent utilization of genetic resources of peach [Prunus persica (‘Quetta’ from India, ‘John Rivers’ from England, and ‘Lippiatts’ (L.) Batsch] and Japanese plum (P. salicina Lindl. and hybrids) has from New Zealand) were critical to the development of modern been limited in the United States compared with that of many crops. nectarines in California (Taylor, 1959). However, most fresh-market Difficulties in collection, importation, and quarantine throughput have peach breeding programs in the United States have used germplasm limited the germplasm available. Prunus is more difficult to preserve developed in the United States for cultivar development (Okie, 1998). because more space is needed than for small fruit crops, and the shorter Only in New Jersey was there extensive hybridization with imported life of trees relative to other tree crops because of disease and insect clones, and most of these hybrids have not resulted in named cultivars problems. Lack of suitable rootstocks has also reduced tree life. The (Blake and Edgerton, 1946). trend toward fewer breeding programs, most of which emphasize In recent years, interest in collecting and utilizing novel germplasm “short-term” (long-term compared to most crops) commercial cultivar has increased. For example, non-melting clingstone peaches from development to meet immediate industry needs, has also contributed Mexico and Brazil have been used in the joint USDA–Univ. of to reduced use of exotic material. Georgia–Univ. of Florida breeding program for the development of Probably all modern commercial peaches grown in the United early ripening, non-melting, fresh-market peaches for low-chill areas States are related to ‘Chinese Cling’, a peach imported from China (Beckman and Sherman, 1996). -

(Prunus Spp) Using Random Amplified Microsatellite Polymorphism Markers

Assessment of genetic diversity and relationships among wild and cultivated Tunisian plums (Prunus spp) using random amplified microsatellite polymorphism markers H. Ben Tamarzizt, S. Ben Mustapha, G. Baraket, D. Abdallah and A. Salhi-Hannachi Laboratory of Molecular Genetics, Immunology & Biotechnology, Faculty of Sciences of Tunis, University of Tunis El Manar, El Manar, Tunis, Tunisia Corresponding author: A. Salhi-Hannachi E-mail: [email protected] Genet. Mol. Res. 14 (1): 1942-1956 (2015) Received January 8, 2014 Accepted July 8, 2014 Published March 20, 2015 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.4238/2015.March.20.4 ABSTRACT. The usefulness of random amplified microsatellite polymorphism markers to study the genetic diversity and relationships among cultivars belonging to Prunus salicina and P. domestica and their wild relatives (P. insititia and P. spinosa) was investigated. A total of 226 of 234 bands were polymorphic (96.58%). The 226 random amplified microsatellite polymorphism markers were screened using 15 random amplified polymorphic DNA and inter-simple sequence repeat primers combinations for 54 Tunisian plum accessions. The percentage of polymorphic bands (96.58%), the resolving power of primers values (135.70), and the polymorphic information content demonstrated the efficiency of the primers used in this study. The genetic distances between accessions ranged from 0.18 to 0.79 with a mean of 0.24, suggesting a high level of genetic diversity at the intra- and interspecific levels. The unweighted pair group with arithmetic mean dendrogram Genetics and Molecular Research 14 (1): 1942-1956 (2015) ©FUNPEC-RP www.funpecrp.com.br Genetic diversity of Tunisian plums using RAMPO markers 1943 and principal component analysis discriminated cultivars efficiently and illustrated relationships and divergence between spontaneous, locally cultivated, and introduced plum types. -

Report of a Working Group on Prunus: Sixth and Seventh Meetings

European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Report of a Working Resources ECP GR Group on Prunus Sixth Meeting, 20-21 June 2003, Budapest, Hungary Seventh Meeting, 1-3 December 2005, Larnaca, Cyprus L. Maggioni and E. Lipman, compilers IPGRI and INIBAP operate under the name Bioversity International Supported by the CGIAR European Cooperative Programme for Plant Genetic Report of a Working Resources ECP GR Group on Prunus Sixth Meeting, 20 –21 June 2003, Budapest, Hungary Seventh Meeting, 1 –3 December 2005, Larnaca, Cyprus L. Maggioni and E. Lipman, compilers ii REPORT OF A WORKING GROUP ON PRUNUS: SIXTH AND SEVENTH MEETINGS Bioversity International is an independent international scientific organization that seeks to improve the well- being of present and future generations of people by enhancing conservation and the deployment of agricultural biodiversity on farms and in forests. It is one of 15 centres supported by the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR), an association of public and private members who support efforts to mobilize cutting-edge science to reduce hunger and poverty, improve human nutrition and health, and protect the environment. Bioversity has its headquarters in Maccarese, near Rome, Italy, with offices in more than 20 other countries worldwide. The Institute operates through four programmes: Diversity for Livelihoods, Understanding and Managing Biodiversity, Global Partnerships, and Commodities for Livelihoods. The international status of Bioversity is conferred under an Establishment Agreement which, by January 2006, had been signed by the Governments of Algeria, Australia, Belgium, Benin, Bolivia, Brazil, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Chile, China, Congo, Costa Rica, Côte d’Ivoire, Cyprus, Czech Republic, Denmark, Ecuador, Egypt, Greece, Guinea, Hungary, India, Indonesia, Iran, Israel, Italy, Jordan, Kenya, Malaysia, Mali, Mauritania, Morocco, Norway, Pakistan, Panama, Peru, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Senegal, Slovakia, Sudan, Switzerland, Syria, Tunisia, Turkey, Uganda and Ukraine. -

Prunus Tomentosa

Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Species: Prunus tomentosa (prue'nus to-men-toh'sah) Manchu Cherry; Nanking Cherry Cultivar Information * See specific cultivar notes on next page. Ornamental Characteristics Size: Shrub > 8 feet Height: 8' - 9' (spread 15') Leaves: Deciduous Shape: rounded Ornamental Other: full sun; tolerates extreme cold and wind Environmental Characteristics Light: Full sun Hardy To Zone: 3a Soil Ph: Can tolerate acid to alkaline soil (pH 5.0 to 8.0) Environmental Other: full sun; tolerates extreme cold and wind Insect Disease No diseases listed Bare Root Transplanting Any Other Edible fruit native to China and Japan; plant in groups for best fruiting 1 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Moisture Tolerance Occasionally saturated Consistently moist, Occasional periods of Prolonged periods of or very wet soil well-drained soil dry soil dry soil 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 2 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Cultivars for Prunus tomentosa Showing 1-3 of 3 items. Cultivar Name Notes Leucocarpa 'Leucocarpa' - white fruits Orient 'Orient' - large orange-red fruits Pink Candles 'Pink Candles' - upright spreading form; deeply veined green foliage; pink flowers appear before foliage; small edible red cherries are excellent for jellies and preserves, also attracting birds; very hardy; grows to 5 - 10' tall x 10 - 20' wide 3 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Photos Prunus tomentosa - Flowers Prunus tomentosa - Flowers 4 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus tomentosa - Leaves Prunus tomentosa - Habit 5 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus tomentosa - Habit Prunus tomentosa - Habit 6 Woody Plants Database [http://woodyplants.cals.cornell.edu] Prunus tomentosa - Flowers 7. -

Giresun Ve İlçelerinde Yetiştirilen Yerel Erik Çeşitlerinin Pomolojik Ve Morfolojik Özeliklerinin Belirlenmesi

Araştırma Makalesi Ziraat Mühendiliği (372), 101-115 DOI: 10.33724/zm.956357 Giresun ve İlçelerinde Yetiştirilen Yerel Erik Çeşitlerinin Pomolojik ve Morfolojik Özeliklerinin Belirlenmesi The Determination of Pomological and Morphological Properties of The Local Plum Types Grown in Giresun and Districts ÖZET Canan ÖNCÜL1 Ahmet AYGÜN2* Bu araştırma Giresun ili Merkez, Bulancak, Keşap İlçelerinde 2016-2017 yılları arasında yürütülmüştür. Çalışma yapılan 1 T.C. Tarım ve Orman Bakanlığı, Giresun İl alanda 20 farklı isimde anılan yerel erik çeşidi belirlenmiştir. Müdürlüğü, Giresun Belirlenen erik çeşitlerinin ağaç özellikleri ve meyve özellikleri 0000-0001-9270-7051 tespit edilmiştir. Belirlenen yerel erik çeşitlerinin ortalama meyve ağırlığı 8.02-169.40 g, meyve eni 20.65-42.06 mm, meyve boyu 2Kocaeli Üniversitesi, Fen Edebiyat Fakültesi, Biy- oloji Bölümü, 41380, Kocaeli, Türkiye/ Kırgızistan 25.42-42.89 mm, meyve yüksekliği 23.33-43.67 mm, meyve Türkiye Manas Üniversitesi, Ziraat Fakültesi, sapı uzunluğu 11.63-17.64 mm, meyve sapı çapı 0.80-2.53 mm, Bahçe ve Tarla Bitkileri Bölümü, 720044, Bişkek, çekirdek ağırlığı 0.31-1.61 g, titre edilebilir asitlik %1.15-2.83, Kırgızistan. pH 2.13-3.83, suda çözünebilir kuru madde miktarının %7.12- 0000-0001-7745-3380 18.47 olarak değişim gösterdiği tespit edilmiştir. Erik çeşitlerinde tomurcuk kabarması 25 Ocak-18 Mart tarihleri arasında, tomurcuk patlaması 8 Şubat-23 Mart tarihleri arasında, İlk Sorumlu Yazar * : [email protected] çiçeklenme 20 Şubat-27 Mart tarihleri arasında, tam çiçeklenme 1 Mart ile 9 Nisan tarihleri arasında, çiçeklenme sonu 10 Mart- 20 Nisan tarihleri arasında gerçekleşmiştir. Eriklerin hasat tarihleri ise 18 Haziran-31 Ağustos tarihleri arasında 75 günlük bir periyotta dağılım göstermiştir. -

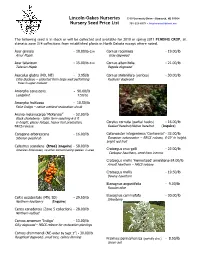

Nursery Price List

Lincoln-Oakes Nurseries 3310 University Drive • Bismarck, ND 58504 Nursery Seed Price List 701-223-8575 • [email protected] The following seed is in stock or will be collected and available for 2010 or spring 2011 PENDING CROP, all climatic zone 3/4 collections from established plants in North Dakota except where noted. Acer ginnala - 18.00/lb d.w Cornus racemosa - 19.00/lb Amur Maple Gray dogwood Acer tataricum - 15.00/lb d.w Cornus alternifolia - 21.00/lb Tatarian Maple Pagoda dogwood Aesculus glabra (ND, NE) - 3.95/lb Cornus stolonifera (sericea) - 30.00/lb Ohio Buckeye – collected from large well performing Redosier dogwood Trees in upper midwest Amorpha canescens - 90.00/lb Leadplant 7.50/oz Amorpha fruiticosa - 10.50/lb False Indigo – native wetland restoration shrub Aronia melanocarpa ‘McKenzie” - 52.00/lb Black chokeberry - taller form reaching 6-8 ft in height, glossy foliage, heavy fruit production, Corylus cornuta (partial husks) - 16.00/lb NRCS release Beaked hazelnut/Native hazelnut (Inquire) Caragana arborescens - 16.00/lb Cotoneaster integerrimus ‘Centennial’ - 32.00/lb Siberian peashrub European cotoneaster – NRCS release, 6-10’ in height, bright red fruit Celastrus scandens (true) (Inquire) - 58.00/lb American bittersweet, no other contaminating species in area Crataegus crus-galli - 22.00/lb Cockspur hawthorn, seed from inermis Crataegus mollis ‘Homestead’ arnoldiana-24.00/lb Arnold hawthorn – NRCS release Crataegus mollis - 19.50/lb Downy hawthorn Elaeagnus angustifolia - 9.00/lb Russian olive Elaeagnus commutata -

Prunus Cerasus Var. Marasca)

86 S. PEDISI] et al.: Anthocyanins in Sour Cherries, Food Technol. Biotechnol. 48 (1) 86–93 (2010) ISSN 1330-9862 original scientific paper (FTB-2300) Effect of Maturity and Geographical Region on Anthocyanin Content of Sour Cherries (Prunus cerasus var. marasca) Sandra Pedisi}¹*, Verica Dragovi}-Uzelac², Branka Levaj² and Dubravka [kevin2 1Faculty of Food Technology and Biotechnology, Zadar Centre, P. Kasandri}a 6, HR-23000 Zadar, Croatia 2Faculty of Food Technology and Biotechnology, University of Zagreb, Pierottijeva 6, HR-10000 Zagreb, Croatia Received: June 15, 2009 Accepted: December 2, 2009 Summary The influence of different stages of maturity on the anthocyanin content and colour parameters in three sour cherry Marasca ecotypes grown in two Dalmatian geographical regions has been studied. Anthocyanins were determined by HPLC-UV/VIS PDA analysis and the colour of fruit flesh and skin was measured by tristimulus colourimeter (CIELAB system). The major anthocyanins in all ecotypes at all stages of maturity were cyanidin 3-glucosylrutinoside and cyanidin 3-rutinoside, whereas pelargonidin glycosides were de- termined in lower concentrations. During ripening, anthocyanins did not change uni- formly, but in most ecotypes they were determined in higher concentrations at the last stage of maturity (3.18 to 19.75 g per kg of dry matter). The formation of dark red, almost black colour in ripe Marasca cherries decreased redness (a*), brightness (L*) and colour intensity (C*). The results of two-way ANOVA test indicated that the growing region sig- nificantly influenced the accumulation of individual anthocyanins and L* value during ripening, while ecotype and the interaction between the growing region and the ecotype significantly affected total anthocyanin content of sour cherry. -

Number 3, Spring 1998 Director’S Letter

Planning and planting for a better world Friends of the JC Raulston Arboretum Newsletter Number 3, Spring 1998 Director’s Letter Spring greetings from the JC Raulston Arboretum! This garden- ing season is in full swing, and the Arboretum is the place to be. Emergence is the word! Flowers and foliage are emerging every- where. We had a magnificent late winter and early spring. The Cornus mas ‘Spring Glow’ located in the paradise garden was exquisite this year. The bright yellow flowers are bright and persistent, and the Students from a Wake Tech Community College Photography Class find exfoliating bark and attractive habit plenty to photograph on a February day in the Arboretum. make it a winner. It’s no wonder that JC was so excited about this done soon. Make sure you check of themselves than is expected to seedling selection from the field out many of the special gardens in keep things moving forward. I, for nursery. We are looking to propa- the Arboretum. Our volunteer one, am thankful for each and every gate numerous plants this spring in curators are busy planting and one of them. hopes of getting it into the trade. preparing those gardens for The magnolias were looking another season. Many thanks to all Lastly, when you visit the garden I fantastic until we had three days in our volunteers who work so very would challenge you to find the a row of temperatures in the low hard in the garden. It shows! Euscaphis japonicus. We had a twenties. There was plenty of Another reminder — from April to beautiful seven-foot specimen tree damage to open flowers, but the October, on Sunday’s at 2:00 p.m. -

The Ornamental Trees of South Dakota N.E

South Dakota State University Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange South Dakota State University Agricultural Bulletins Experiment Station 4-1-1931 The Ornamental Trees of South Dakota N.E. Hansen Follow this and additional works at: http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_bulletins Recommended Citation Hansen, N.E., "The Ornamental Trees of South Dakota" (1931). Bulletins. Paper 260. http://openprairie.sdstate.edu/agexperimentsta_bulletins/260 This Bulletin is brought to you for free and open access by the South Dakota State University Agricultural Experiment Station at Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bulletins by an authorized administrator of Open PRAIRIE: Open Public Research Access Institutional Repository and Information Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Bulletin 260 April, 1931 The Ornamental Trees of South Dakota Figure I-The May Day Tree. Horticulture Department Agricultural Experiment Station South Dakota State College of Agriculture and Mechanic Arts Brookings, S. Dak. The Ornamental Trees of South Dakota N. E. Hansen This bulletin describes the deciduous trees. By deciduous trees is meant those that shed their leaves in winter. The evergreens of South Dakota are described in bulletin 254, October 1930. A bulletin on "The Ornamental Shrubs of South Dakota" is ready for early publication. The following list should be studied in connection with the trees described in South Dakota bulletin 246, "'The Shade, Windbreak and Timber Trees of South Dakota," 48 pages, March 1930. All the trees in both bulletins have ornamental value in greater or less degree.