How Content Preferences Limit the Reach of Voting Aids

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Voting Over a Distributed Ledger: an Interdisciplinary Perspective

Voting over a distributed ledger: An interdisciplinary perspective Amrita Dhillon* Grammateia Kotsialou† Peter McBurney‡ Luke Riley§ King’s College London, UK August 30, 2020 Abstract This work discusses the potential of a blockchain based infrastructure for a decentralised online voting platform. When compared to paper based voting, online voting can vastly increase the speed that votes can be counted, expand the overall accessibility of the election system and decrease the cost of turnout. Yet despite these advantages, online voting for political office is subject to fraud at various levels due to its centralised nature. In this paper, we describe a gen- eral architecture of a centralised online voting system and detail which areas of such a system are vulnerable to electoral fraud. We then proceed to introduce the key ideas underlying blockchain technology as a decentralised mechanism that can address these problems. We discuss the advantages and weaknesses of the blockchain technology, the protocols the technology uses and what criteria a good blockchain protocol should satisfy (depending on the voting applica- tion). We argue that the decentralisation inherent in the blockchain technology could increase the public’s trust in national elections, as well as eliminate voter impersonation and double voting. We conclude with a discussion regarding *Department of Political Economy, email: [email protected] †Department of Political Economy, email: [email protected] ‡Department of Informatics, email: [email protected] §Department of Informatics, email: [email protected] 1 how economists and social scientists can collaborate with the blockchain com- munity in a research agenda on the design of efficient blockchain protocols and new voting systems such as liquid democracy. -

Project Vote Smart General Population and Youth Survey on Civic Engagement: Summer, 1999

Project Vote Smart General Population and Youth Survey on Civic Engagement: Summer, 1999 Preliminary Results of a Nationwide Survey Project Vote Smart One Common Ground Phillipsburg, Montana Richard Kimball, Executive Director The Thomas S. Foley Institute for Public Policy and Public Service Washington State University Pullman, Washington Lance LeLoup, Director Nicholas Lovrich, Faculty Associate The Program for Governmental Research and Education Oregon State University Corvallis, Oregon Brent Steel, Director Robert Sahr, Faculty Associate Michelle Kittrell, Student Associate September 1999 Executive Summary A number of noteworthy findings from the Project Vote Smart/Pew Charitable Trusts 1999 Survey deserve special attention. This report sets forth a complete listing of survey findings from telephone interviews completed (July 12 to August 10) with 454 eighteen to twenty-five year olds and 872 persons of age twenty-six and over. These findings concerning younger voting-age citizens deserve special attention: ♦ Attention to Civic Affairs: Younger respondents pay less attention to government at all levels than older respondents. Although each group attends most to national affairs, the gap between younger and older respondents is especially pronounced about national government, where 22% of younger and 37% of older respondents indicated they pay “a lot of attention.” Among younger respondents, 12% said they pay “no attention” while only 4% of older respondents indicate that level of (in)attention. ♦ Trust in Government: A striking similarity noted is that both age groups express most trust in local government, though another 24% (younger) and 19% (older) indicate trust in “none of them.” ♦ Important Problems: Younger respondents express more concern than older respondents about jobs and the economy, about equal concern on education and crime, and less concern on health, moral concerns, and Social Security. -

Interactive Display of Complex Political Data in an Effort to Promote Social Change

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 2010 Interactive display of complex political data in an effort to promote social change Tyler Travitz Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Travitz, Tyler, "Interactive display of complex political data in an effort to promote social change" (2010). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Rochester Institute of Technology A Master of Fine Arts Thesis for Computer Graphics Design submitted to the Faculty of the College of Imaging Arts and Sciences INTERACTIVE DISPLAY OF COMPLEX POLITICAL DATA IN AN EFFORT TO PROMOTE SOCIAL CHANGE Tyler A. Travitz May 5, 2010 02. APPROVALS Chief Advisor: Chris Jackson, Associate Professor, Computer Graphics Design Signature of Chief Advisor Date Associate Advisor: Alex Bitterman, Associate Professor, Graphic Design Signature of Associate Advisor Date Associate Advisor: Nancy Doubleday, Associate Professor, Interactive Games and Media Signature of Associate Advisor Date Chair Person, School of Design: Patti Lachance Signature of Chairperson Date Travitz 2 REPRODUCTION GRANTED I, Tyler A. Travitz, hereby grant permission to Rochester Institute of Technology to reproduce my thesis documentation in whole or part. Any reproduction will not be for commercial use or profit. Signature of Author Date INCLUSION IN THE RIT DIGITAL MEDIA LIBRARY ELECTRONIC THESIS AND DISSERTATION (ETD) ARCHIVE: I, Tyler A. Travitz, additionally grant to Rochester Institute of Technology Digital Media Library the non-exclusive license to archive arid provide electronic access to my thesis in whole or in part in all forms of media in perpetuity. -

UNOFFICIAL COPY of HOUSE BILL 1368 EMERGENCY BILL G1 (6Lr2473) ENROLLED BILL -- Ways and Means/Education, Health, and Environmental Affairs

UNOFFICIAL COPY OF HOUSE BILL 1368 EMERGENCY BILL G1 (6lr2473) ENROLLED BILL -- Ways and Means/Education, Health, and Environmental Affairs -- Introduced by Delegates Hixson, Patterson Patterson, Hixson , Cardin, King, and McKee McKee, Ross, Bozman, C. Davis, Goodwin, Gordon, Healey, Heller, Howard, Kaiser, Marriott, Ramirez, and Rosenberg Rosenberg, and Conroy Read and Examined by Proofreaders: _____________________________________________ Proofreader. _________ ____________________________________ Proofreader. Sealed with the Great Seal and presented to the Governor, for his approval this _____ day of ____________ at ____________________ o'clock, _____M. __________________________________________ ___ Speaker. CHAPTER_______ 1 AN ACT concerning 2 Election Law - Voter Bill of Rights 3 FOR the purpose of requiring a local board of elections to establish, under certain 4 circumstances, a separate precinct to serve certain institutions of higher 5 education; requiring each institution at which a precinct is established to 6 provide certain facilities and services to the local board; requiring that local 7 boa rds, when establishing early voting polling places, select sites that are 8 consistent with certain guidelines and regulations established by the State 9 Board of Elections; requiring certain polling places to be equipped with a certain 10 co mputer device; requiring the Governor to allocate certain resources to 11 implement the requirements of this Act; requiring the Governor to appropriate 12 sufficient funds to reimburse the counties -

Annual Report 2013

The National Institute on Money in State Politics Constructing a New Paradigm 2013 Annual Report www.FollowTheMoney.org NIMSP_13ReportFNL.indd 1 9/6/13 7:53:33 AM Mission The National Institute on Money in State Politics is the only nonpartisan, nonprofit organization revealing the influence of campaign money on state-level elections and public policy in all 50 states. Our comprehensive and verifiable campaign- finance database and relevant issue analyses are available for free through our website FollowTheMoney.org. We encourage transparency and promote independent investigation of state-level campaign contributions by journalists, academic researchers, public-interest groups, government agencies, policymakers, students and the public at large. Constructing a New Paradigm The Institute dove into its engineering trenches this past year, completely rethinking our underlying data architecture that archives 30 million records documenting $28 billion reported in political campaign money. We wanted more speed, more cross-analyses, more options. Our goal was to make the quality of the data impossibly better. In short, we want you to be able to ask anything and find answers, fast. And so, the Institute spent this past year deep in the twists and turns of source codes, to knit and entwine our data pathways in new ways. We closed our eyes and imagined an entirely fresh way of perceiving. We mined the data, reimagined the substructure, sketched possibilities, and wore out markers and erasers on whiteboards. We gave the beta version to academics, journalists, and other major users with instructions to find weaknesses, to probe and try to unravel it, then we braided it into a stronger net, a solid labyrinth of unimpeachable integrity. -

Libraries and Voter Engagement

Libraries and Voter Engagement Voting is one of the greatest privileges and responsibilities of citizenship in the United States. Yet, turnout in national elections is consistently lower than two-thirds of eligible voters. Participation rates among certain demographic groups and in state or local elections are often lower still. There is frequent talk about the critical role of libraries in our democracy. What does that look like in practice? Libraries are nonpartisan, but they are not indifferent. As community. As best institutions that provide access to information, resources, practice before under- programs, and public spaces for all members of a community, taking activities related libraries are a cornerstone for civic engagement. to voting, we recom- mend that you: Across the country, many libraries: check your local provide information about voting and voter registration. voting laws. A good offer services for voters and registrants, such as hosting place to start is polling places. Nonprofit Vote’s convene candidate forums and debates. state-by-state deliver resources and educational programs that resource: increase civic and information literacy. nonprofitvote.org/ This guide provides information and examples of how voting-in-your- libraries of any type, in any community, can meet their state/. National Voter Registration Day at Topeka communities’ needs for information related to voting and ensure that all staff Shawnee Public Library in Kansas encourage full participation in our democratic processes, and volunteers are with a focus on the upcoming 2020 elections. aware of local voting laws as they relate to library activ- ities, and keep your board/administration apprised of programs and activities. -

Smart Voting Starts @ Your Library

Dear Colleagues: Over the past three decades, we have seen a This tipsheet from the American Library decline invoter turnout, smaller attendance at Association provides ideas for how your library political rallies, fewer people engaging in can bean electoral resource foryour community politics ingovernment and a reduced involvement and how libraries can use the election season incivic organizations. And as countries overseas to promote their own issues. Italso includes seek to establish democratic institutions,we a broad listof suggested resources for informa seem to have experienced a deepening cynicism tion on the upcoming elections and American about public affairs inthe United States. democracy and great examples of what Fortunately, this cynicism has sparked a renewed some libraries indifferent parts of the country interest incivic involvement and reinvigorating are doing to facilitate the electoral process. American democracy. We hope that you will share this informa So how can we meet the challenge of tion with your colleagues and encourage library strengthening and maintaining a vigorous users to take advantage of all the important democracy? A good part of the answer lies at resources your libraryhas to offer to ensure our very doorstep-the Iibrary. broadpublic participation during this upcoming The libraryprovides a civic space where election season and in future elections. You can the public can find all sorts of voting information, findan onlineversion of thistipsheet that speak freely,share similar interests and you are welcome to reproduce and distribute at concerns and pursue what they believe is in www.ala.org/kranich/librariesandelections/. their interest.The library isthe one institution Libraries are the cornerstone of democracy. -

REGISTERTO VOTE >LOCATEYOUR POLLING PLACE >BRINGAPPROPRIATE ID >LEARNABOUT the CANDIDATES >SAVETHE DATE

With the Millennial Generation making up nearly 1/4 of the entire electorate in 2012, the youth vote is more important and influential than ever! Many people don’t vote simply because they may not be sure how, may not know who to ask, or may feel ashamed about needing to ask. But voting is a relatively simple task and you can make a big difference by helping educate people on how the process works: >REGISTER TO VOTE >LOCATE YOUR POLLING PLACE >BRING APPROPRIATE ID >LEARN ABOUT THE CANDIDATES >SAVE THE DATE REGISTER Before you can vote in any election, you have to register as a voter. Every state has different registration deadlines and forms. In a majority of states, you have to register at least a month before the election. However, most states have mail-in registration programs and many now offer online registration options! You can find out what the particular guidelines are in your area by contacting your state or local elections bureau or by visiting the Project Vote Smart website. ( www.vote-smart.org/voter_registration _resources.php ) Additionally, Rock the Vote ( www.rockthevote.org ) has an easy-to-use voter registration tool that will help you fill out your state’s voter registration form with your information and tell you when and where you need to mail it. Also, consider being a poll worker. If you’re planning to go to the polls on Election Day, why not consider being a poll worker? Every state needs people to work the polls, and in most states you can actually get paid for serving. -

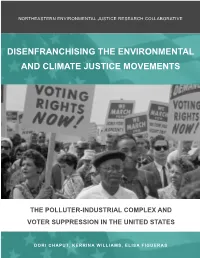

Voter Suppression Report Jan 01

NORTHEASTERN ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE RESEARCH COLLABORATIVE DISENFRANCHISING THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND CLIMATE JUSTICE MOVEMENTS THE POLLUTER-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX AND VOTER SUPPRESSION IN THE UNITED STATES DISENFRANCHISING THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND CLIMATE MOVEMENTS: THEDORI POLLUTER-INDUSTRIAL CHAPUT, COMPLEX KERRINA AND VOTER SUPPRESSION WILLIAMS, IN THE UNITED ELISA STATES FIGUERAS Disenfranchising the Environmental and Climate Justice Movements: The Polluter-Industrial Complex and Voter Suppression in the United States by Dori Chaput, Kerrina Williams, and Elisa Figueras NORTHEASTERN ENVIRONMENTAL JUSTICE RESEARCH COLLABORATIVE January 2021 AUTHORS Dori Chaput Kerrina Williams Elisa Figueras REASEARCH AND EDITORIAL ASSISTANTS Hannah Nivar Dr. Daniel Faber GRAPHIC DESIGN AND PRODUCTION LAYOUT Nell Solomon COLLABORATOR Northeastern Environmental Justice Research Collaborative The Northeastern Environmental Justice Research Collaborative (NEJRC) is a multidis- ciplinary research collaborative made up of scholars engaged in political ecology and environmental justice initiatives. Based at Northeastern University in Boston, the collab- orative works on a wide range of local, regional, national, and international topics and issues. Professor Daniel Faber, a long-time researcher and advocate around environ- mental justice, serves as the Director. Dr. Daniel Faber NEJRC Director Phone: 617-373-2878 Email: [email protected] 360 Huntington Ave, Boston, MA 02115 DISENFRANCHISING THE ENVIRONMENTAL AND CLIMATE MOVEMENTS: ii THE POLLUTER-INDUSTRIAL COMPLEX AND -

Monticello Ballot Guide

ATTENTION VOTERS! Monticello Ballot Guide Candidates for Representative (13th Illinois Congressional District) Endorsements:** Hometown: Women’s Advisory Committee of Taylorville, IL Women for Rodney. Occupation: State Treasurer Dan Rutherford. Project Manager, Rep. Shimkus Illinois Agricultural Association Contact Information: Rodney Davis ACTIVATOR. www.electrodney.com Bond County Sheriff Jeff Brown. (Republican) (309) 306-1318 Champaign County Sheriff Dan Walsh. Governor Jim Edgar. Endorsements:** Hometown: Illinois AFL-CIO. Bloomington, IL American Federation of Teachers. Occupation: Planned Parenthood Action Fund. Family Practice & ER Doctor Human Rights Campaign. Contact Information: David Gill Sierra Club. www.gill2012.org Democracy for America. (Democrat) (217) 391-4367 Endorsements: Hometown: No endorsements listed on website. Edwardsville, IL Occupation: CFO, DNA Polymerase Tech. John Hartman Contact Information: (Independent) www.hartman2012.com No phone listed Candidates for State Senator (51st Illinois Senate District) Endorsements:** Hometown: Illinois Farm Bureau - ACTIVATOR. Mahomet, IL National Rifle Association. Occupation: Congressman Tim Johnson. Attorney, current state Governor Jim Edgar. representative Associated Fire Fighters of Illinois. Rep. Chapin Rose Illinois Chamber of Commerce. Contact Information: (Republican) www.chapinrose.org (217) 493-8549 Candidates for State Representative (101st Illinois House District) Endorsements: Hometown: No endorsements found. Forsyth, IL Occupation: Decatur City Council, state representative Contact Information: Rep. Bill Mitchell [email protected] (Republican) (217) 875-0886 Listed endorsements are limited to six, when available. Either selected directly by candidate (denoted by *) or from their website (denoted by **). Register to Vote TODAY To register, you must: 4 Be at least 18 years old on or before November 6. 4 Be a U.S. citizen. 4 Be a resident of that precinct for at least 30 days prior to election day. -

HOUSE BILL 08-1378 by REPRESENTATIVE(S) Kefalas, Carroll M., Carroll T., Fischer, Frangas, Hodge, Labuda, Madden, Mcgihon, Weiss

NOTE: This bill has been prepared for the signature of the appropriate legislative officers and the Governor. To determine whether the Governor has signed the bill or taken other action on it, please consult the legislative status sheet, the legislative history, or the Session Laws. HOUSE BILL 08-1378 BY REPRESENTATIVE(S) Kefalas, Carroll M., Carroll T., Fischer, Frangas, Hodge, Labuda, Madden, McGihon, Weissmann, and Borodkin; also SENATOR(S) Gordon, Bacon, Groff, Schwartz, Tupa, and Windels. CONCERNING THE USE OF RANKED VOTING METHODS, AND, IN CONNECTION THEREWITH, AUTHORIZING CITIES AND SPECIAL DISTRICTS TO USE RANKED VOTING. Be it enacted by the General Assembly of the State of Colorado: SECTION 1. 1-1-104, Colorado Revised Statutes, is amended BY THE ADDITION OF A NEW SUBSECTION to read: 1-1-104. Definitions. As used in this code, unless the context otherwise requires: (34.4) "RANKED VOTING METHOD" MEANS A METHOD OF CASTING AND TABULATING VOTES THAT ALLOWS ELECTORS TO RANK THE CANDIDATES FOR AN OFFICE IN ORDER OF PREFERENCE AND USES THESE PREFERENCES TO DETERMINE THE WINNER OF THE ELECTION. "RANKED VOTING METHOD" INCLUDES INSTANT RUNOFF VOTING AND CHOICE VOTING OR PROPORTIONAL VOTING AS DESCRIBED IN SECTION 1-7-1003. ________ Capital letters indicate new material added to existing statutes; dashes through words indicate deletions from existing statutes and such material not part of act. SECTION 2. Article 7 of title 1, Colorado Revised Statutes, is amended BY THE ADDITION OF A NEW PART to read: PART 10 RANKED VOTING METHODS 1-7-1001. Short title. THIS PART 10 SHALL BE KNOWN AND MAY BE CITED AS THE "VOTER CHOICE ACT". -

Patrice M. Arent Senate Sponsor

Enrolled Copy H.B. 70 1 REPEAL OF SINGLE-MARK STRAIGHT TICKET VOTING 2 2020 GENERAL SESSION 3 STATE OF UTAH 4 Chief Sponsor: Patrice M. Arent 5 Senate Sponsor: Curtis S. Bramble 6 Cosponsors: Dan N. Johnson Lawanna Shurtliff 7 Cheryl K. Acton Brian S. King Robert M. Spendlove 8 Melissa G. Ballard Karen Kwan Jeffrey D. Stenquist 9 Joel K. Briscoe Carol Spackman Moss Andrew Stoddard 10 Walt Brooks Merrill F. Nelson Steve Waldrip 11 Jennifer Dailey-Provost Lee B. Perry Raymond P. Ward 12 Susan Duckworth Candice B. Pierucci Christine F. Watkins 13 Craig Hall Stephanie Pitcher Elizabeth Weight 14 Suzanne Harrison Marie H. Poulson Mark A. Wheatley 15 Jon Hawkins Marc K. Roberts Mike Winder 16 Sandra Hollins Angela Romero 17 Eric K. Hutchings Rex P. Shipp 18 19 LONG TITLE 20 General Description: 21 This bill amends provisions of the Election Code relating to the manner by which a 22 voter casts a vote for all candidates from one political party. 23 Highlighted Provisions: 24 This bill: 25 < removes provisions from the Election Code that allow an individual to cast a vote 26 for all candidates from one political party without voting for the candidates 27 individually; H.B. 70 Enrolled Copy 28 < removes provisions relating to straight ticket party voting and scratch voting; and 29 < makes technical and conforming changes. 30 Money Appropriated in this Bill: 31 None 32 Other Special Clauses: 33 This bill provides a coordination clause. 34 Utah Code Sections Affected: 35 AMENDS: 36 20A-1-102, as last amended by Laws of Utah 2019, First Special Session,