“Social Justice and Solar Energy Implementation”

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Kutch Basin Forms the North-Western Part of the Western Continental

Basin Introduction :. Kutch basin forms the north-western part of the western continental margin of India and is situated at the southern edge of the Indus shelf at right angles to the southern Indus fossil rift (Zaigham and Mallick, 2000). It is bounded by the Nagar- Parkar fault in the North, Radhanpur-Barmer arch in the east and North Kathiawar fault towards the south. The basin extents between Latitude 22° 30' and 24° 30' N and Longitudes 68° and 72° E covering entire Kutch district and western part of Banaskantha (Santalpur Taluka) districts of Gujarat state. It is an east-west oriented pericratonic embayment opening and deepening towards the sea in the west towards the Arabian Sea. The total area of the basin is about 71,000 sq. km of which onland area is 43,000 sq.km and offshore area is 28,000 sq.km. upto 200 bathymetry. The basin is filled up with 1550 to 2500m of Mesozoic sediments and 550m of Tertiary sediments in onland region and upto 4500m of Tertiary sediments in offshore region (Well GKH-1). The sediment fill thickens from less than 500m in the north to over 4500m in the south and from 200m in the east to over 14,000m in the deep sea region towards western part of the basin indicating a palaeo-slope in the south-west. The western continental shelf of India, with average shelf break at about 200 m depth, is about 300 km wide off Mumbai coast and gradually narrows down to 160 km off Kutch in the north. -

J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J J

j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j DhananJa}arao Gadglillbrary j 111111111111 InlllIlll Illilllill DIIIIH GIPE-PUNE-IOI540 j j f '----- - j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j j SELECTIONS FI10M THE RECORDS OF THE BOMBAY GOVERNMENT. ~ (IN Two PARTS.)-NEW SERIES. Y;-"'~Vtlf _____ PART I. REPORT~ ON THE RESOURCES, &0., OF THE • DISTRICTS OF NADIAD, ~IT~R, w)NDE~, JUJAPUR, DHOLKA. DHANDHUKA, AND GOGH( THE TAPPA OF NAPAD, AND THE . KASBA OF RANPUR, IN GUJARAT: . / ACCOMPANIED EY ERIEF NO~ RELATIVE TO THE OONDITION OF THAT PROVINCE PREVIOUS TO THE OLOSE OF THE LAST CENTURY. A • of': .. ~_. ~,..._~ __ .... __ ~ ____ ~ WI';['H MEMOIRS ON 'THE DISTRICT~_ O~ JHALAVAD: KaTHIAWAR PROPER, MACHU KAN"'tHA, NAVANAGAR • . GOHELVAD, PORBANDAR, SORATH, AND HALAR, IN KATEIAW AP :" _)._1 ACCOMPANIED BY MISCELLANEOU~ INFORMATION ,CONNECTED WJTH THAT PBOYINCE ~ By (THE LATE) COLONEL ALEXANDER WALKER PART. II., REPORTS OF THE , " MEASURES; tJOMMENCING WITH 'ra.~ YEA:& 180;), AD6PTED) IN CONCERT WITH THE GOVERNMENT, BY. -THE LA~E COLONEL- ALEXANDER WALKER; ANP SuBSEQUENTLY BYMlt r.-V: WILLOUGHBY, POLITICAL AGENT IN KATHIAWAR, AND BY HIS SUCCESSORS, FOR THE SUPPRESSION OF FEMALE INFANTI CIDE1N THAT PROVINCE . •C01'lPILED &r EDITED BY R. HUGHES TROnS. ASSISTANT SEORETARY, POLITICAL DEPARTMEl!T , ~.O'mbaJl! REPRINTED AT THE GOVER;NMENT CENTRAL PRESS. -1~93. ~B3TRACT -OF CONTENTS. PARTt fAG.e. Qt1lARA~-Reporta on the ResourCt>s, &c., uf.the j;lhtrll:ts of Nll.duld, Mdtar, Mahudha, BIJapur, Dholka, Dhl.llldhuka and GogN:, the T'lppa of Napa.r, and thE' Kasba of Ranpur In the Plovlnce of GujarMf. -

Addedndum to Petition 1914.Pdf

BEFORE THE GUJARAT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION GANDHINAGAR CASE NO. 1914/2020 Determination of Aggregate Revenue Requirement And Tariff of FY 2021-22 Under GERC (Multi Year Tariff) Regulations, 2016 along with other Guidelines and Directions issued by the GERC from time to time AND under Part VII (Section 61 to Section 64) of the Electricity Act, 2003 read with the relevant Guidelines Filed by:- Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Corp. Office: Paschim Gujarat Vij Seva Sadan, Off. Nana Mava Main Road, Laxminagar, Rajkot– 360004. Determination of ARR & Tariff for FY 2021-22 BEFORE THE GUJARAT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION GANDHINAGAR Filing No: Case No: 1914/2020 IN THE MATTER OF Filing of the Petition for determination of ARR & Tariff for FY 2021-22, under GERC (Multi Year Tariff) Regulations, 2016 along with other Guidelines and Directions` issued by the GERC from time to time AND under Part VII (Section 61 to Section 64) of the Electricity Act, 2003 read with the relevant Guidelines AND IN THE MATTER OF Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Limited, Paschim Gujarat Vij Seva Sadan, Off. Nana Mava Main Road, Laxminagar, Rajkot – 360004. PETITIONER Gujarat Urja Vikas Nigam Limited Sardar Patel Vidyut Bhavan, Race Course, Vadodara - 390 007 CO-PETITIONER THE PETITIONER ABOVE NAMED RESPECTFULLY SUBMITS Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Limited 63 Determination of ARR & Tariff for FY 2021-22 TABLE OF CONTENTS SECTION 1. INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................... 68 1.1. PREAMBLE ............................................................................................................ -

Merchants Where Online Debit Card Transactions Can Be Done Using ATM/Debit Card PIN Amazon IRCTC Makemytrip Vodafone Airtel Tata

Merchants where online Debit Card Transactions can be done using ATM/Debit Card PIN Amazon IRCTC Makemytrip Vodafone Airtel Tata Sky Bookmyshow Flipkart Snapdeal icicipruterm Odisha tax Vodafone Bharat Sanchar Nigam Air India Aircel Akbar online Cleartrip Cox and Kings Ezeego one Flipkart Idea cellular MSEDC Ltd M T N L Reliance Tata Docomo Spicejet Airlines Indigo Airlines Adler Tours And Safaris P twentyfourBySevenBooking Abercrombie n Kent India Adani Gas Ltd Aegon Religare Life Insur Apollo General Insurance Aviva Life Insurance Axis Mutual Fund Bajaj Allianz General Ins Bajaj Allianz Life Insura mobik wik Bangalore electricity sup Bharti axa general insura Bharti axa life insurance Bharti axa mutual fund Big tv realiance Croma Birla sunlife mutual fund BNP paribas mutural fund BSES rajdhani power ltd BSES yamuna power ltd Bharat matrimoni Freecharge Hathway private ltd Relinace Citrus payment services l Sistema shyam teleservice Uninor ltd Virgin mobile Chennai metro GSRTC Club mahindra holidays Jet Airways Reliance Mutual Fund India Transact Canara HSBC OBC Life Insu CIGNA TTK Health Insuranc DLF Pramerica Life Insura Edelweiss Tokio Life Insu HDFC General Insurance IDBI Federal Life Insuran IFFCO Tokio General Insur India first life insuranc ING Vysya Life Insurance Kotak Mahindra Old Mutual L and T General Insurance Max Bupa Health Insurance Max Life Insurance PNB Metlife Life Insuranc Reliance Life Insurance Royal Sundaram General In SBI Life Insurance Star Union Daiichi Life TATA AIG general insuranc Universal Sompo General I -

Before the Gujarat Electricity Regulatory Commission

BEFORE THE GUJARAT ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION GANDHINAGAR Petition No 1712 of 2018 In the matter of: Petition under the provision of Electricity Act, 2003 read with GERC (Terms and Conditions of Intra- State Open Access) Regulations, 2011 and in the matter of seeking refund of amount of transmission wheeling charges paid by the Petitioner company Under Protest and in the matter of decision/ order dated 10.05.2017 passed by the Respondent authority rejecting the request/application of refund of amount paid towards Exit Option Charge for Wind Mill No. ADO-36 made by the Petitioner company. Petitioner: Gokul Refoils and Solvent, Gokul House, 43, Shreemali Co-Operative Housing Soc. Ltd., Opp. Shikhar Building, Navrangpura, Ahmedabad. Co-Petitioner: Gokul Agri International Ltd, State Highway No. 41, Near Sujanpur Patia, Sidhpur, District: Patan, Pin Code – 384151 Represented by: Learned Advocate Shri Satyan Thakkar and Shri Nisarg Rawal V/s. Respondent: Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Ltd. Sardar Patel Vidyut Bhavan, Race Course, Vadodara- 390 007. Represented by: Learned Sernior Advocate Shri M. G. Ramchandran with Advocate Ms. Ranjitha Ramchandran and Ms. Venu Birappa CORAM: Shri Anand Kumar, Chairman Shri P. J. Thakkar, Member Date: 09/03/2020 ORDER 1 1 The present petition has been filed by M/s Gokul Refoils & Solvent Limited and M/s Gokul Agri International Limited seeking following prayer: “The Commission may be pleased to quash and set aside the impugned decision/order dated 10.05.2017 passed by the Additional Engineer (R&C), Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Limited and further be pleased to direct the Gujarat Energy Transmission Corporation Limited i.e. -

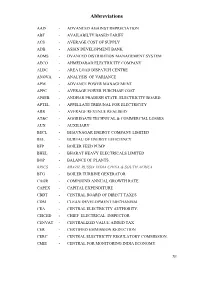

09 List of Abbreviations.Pdf

Abbreviations AAD - ADVANCED AGAINST DEPRECIATION ABT - AVAILABILTY BASED TARIFF ACS - AVERAGE COST OF SUPPLY ADB - ASIAN DEVELOPMENT BANK ADMS - DVANCED DISTRIBITION MANAGEMENT SYSTEM AECO - AHMEDABAD ELECTRICITY COMPANY ALDC - AREA LOAD DISPATCH CENTRE ANOVA - ANALYSIS OF VARIANCE. APM - ADVANCE POWER MANAGEMENT APPC - AVERAGE POWER PURCHASE COST APSEB - ANDHAR PRADESH STATE ELECTRICITY BOARD. APTEL - APPELLATE TRIBUNAL FOR ELECTRICITY ARR - AVERAGE REVENUE REALISED AT&C - AGGREGATE TECHNICAL & COMMERCIAL LOSSES AUX - AUXILIARY BECL - BHAVNAGAR ENERGY COMPANY LIMITED BEE - BUREAU OF ENERGY EFFICIENCY BFP - BOILER FEED PUMP BHEL - BHARAT HEAVY ELECTRICALS LIMITED BOP - BALANCE OF PLANTS. BRICS - BRAZIL RUSSIA INDIA CHINA & SOUTH AFRICA BTG - BOILER TURBINE GENERATOR CAGR - COMPOUND ANNUAL GROWTH RATE CAPEX - CAPITAL EXPENDITURE CBDT - CENTRAL BOARD OF DIRECT TAXES CDM - CLEAN DEVELOPMENT MECHANISM CEA - CENTRAL ELECTRICITY AUTHORITY. CEICED - CHIEF ELECTRICAL INSPECTOR. CENVAT - CENTRALIZED VALUE ADDED TAX CER - CERTIFIED EMMISSION REDUCTION CERC - CENTRAL ELECTRICITY REGULATORY COMMISSION. CMIE - CENTRAL FOR MONITORING INDIA ECONOMY. XI CNG - COMPRESSED NATURAL GAS COC - COST OF CAPITAL COD - COMMERCIAL OPERATION DATE COGS - COST OF GOODS SOLD COP - COST OF PRODUCTION CPCB - CENTRAL POLLUTION BOARD CPL - COASTAL POWER LIMITED CPP - CAPTIVE POWER PLANT CPPs - CAPTIVE POWER PLANTS CRISIL - CREDIT RATING INFORMATION SERVICES OF INDIA LIMITED CSS - CROSS SUBSIDY SURCHARGE CST - CENTRAL SALES TAX CTU - CENTRAL TRANSMISSION UTILITY. CVPF -

Presentation (State Updates)

State Updates – Presentations • Andhra Pradesh • Delhi • Gujarat • Haryana • Karnataka • Maharashtra • Tamil Nadu 1 Andhra Pradesh Power Sector Status and Issues Ahead Presentation by People’s Monitoring Group on Electricity Regulation (PMGER) Hyderabad, Andhra Pradesh 22nd- 23rd March 2007, Mumbai 1 Reform Milestones 2 1 Reform Milestones in AP APSEB Unbundling Financial autonomy Bulk supply & AP Reforms Unbundled into provided to Discoms. trading vested Bill passed into APGenco / Distribution Citizens charter with Discoms in Assembly APTransco Companies introduced as per EA 2003 Apr’98 Feb’99 Apr’00 Apr’02 June 05’ Tripartite agreement with employees on reform program Feb’97 Mar’99 Oct’02 Dec 05’ Employees 7th ARR & Govt. APERC allocated to Tariff filing policy establish all companies made as statement ed through per ACT issued options 2003 Key statistics 4 2 KEY STATISTICS APTRANSCO & DISCOMs APTRANSCO NPDCL Headquarters HYD Headquarters Warangal Consumers 3.47m ADILABAD SRIKAKULAM NIZAMABAD KARIMNAGAR VIJAYNAGARAM WARANGAL MEDAK VISHAKAPATNAM KHAMMAM EAST RANGAREDDY GODAVARI NALGONDA WEST GODAVARI EPDCL CPDCL MAHABOOB NAGAR KRISHNA GUNTUR Headquarters Vizag Headquarters HYD Consumers 3.57m PRAKASAM Consumers 5.61m KURNOOL BAY OF BENGAL ANANTAPUR NELLORE CUDDAPAH SPDCL CHITTOOR Headquarters Tirupati Consumers 5.20m 5 A snapshot of the AP Power Sector Structure Percentage procured from various Key Statistics of Power Sector in sources AP 49% 33% 14% 4% Total Number of 1.73 Cr APGENCO CGS IPPs / JVs NCEs Consumers Per Capita Consumption -

Draft Proposal

DISTRICT PRIMARY EDUCATION PROGRAMME II BANASKANTHA GUJARAT DRAFT PROPOSAL 1996-2003 NOVEMBER 1995 UORARY & DOCUfAEf^TATlCN National lostituu oi Educat PlanQing and Admini*tratio- . 17-B, Sri Aurobindo Marj, D»te.................. CONTENTS EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 2 1. INTRODUCTION: PROFILE AND BACKGROUND 4 2. PRESENT STATUS OF PRIMARY EDUCATION 14 3. PROGRAMME OBJECTIVE, APPROACH AND STRATEGIES 36 4. PROGRAMME COMPONENTS 42 5. FINANCIAL ESTIMATES 60 6. MANAGEMENT STRUCTURES AND MONITORING PROCEDURES 77 ANNEXURE 1 81 ANNEXURE 2 89 DISTRICT PRIMARY EDUCATION PROGRAMME II BANASKANTHA DISTRICT (GUJARAT) DRAFT PROPOSAL (1996-2003) This proposal has been drawn up after a series of consulta tions at the district level with elected panchayat representa tives, administrators, school teachers, inspectors, non-govern- mental organizations, educationists and others interested in education. Various core groups, constituted for the purpose, discussed different aspects of educational development like improving access, promoting retention and achievement, civil works, teacher training etc. Details about the workshops conduct ed as part of the planning process and the composition of the core groups are presented in Annexure 1. (This draft is to be treated as tentative, pending the incorporation of the benchmark surveys on minimum levels of learning, and social assessment studies. These exercises are expected to be completed shortly.) Keeping in mind the suggestions regarding the components of the plan (DPEP Guidelines, pg. 24), this draft plan document is divided into the following sections: 1. Introduction: profile and background of Banaskantha. 2. Present status of primary education. 3. Programme objectives and gaps to be bridged; approach to, and strategies for, primary education planning. 4. Programme components and phasing. -

Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Well Comes

Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Well Comes Vibrant Gujarat Global Investors Summit-2007 SUPPLY VOLTAGE Contract Supply Demand Voltage Up to At 11 KV/ 22KV 4000 KVA Above At 66 KV 4000 KVA and above Where to apply for Power Connection Name of DISCOM Name of Districts Madhya Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Vadodara, Anand, Kheda, (MGVCL) Vadodara Panchmahal, Dahod Uttar Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Ahmedabad (except city), (UGVCL) Mehsana Gandhinagar (except city), Mehsana, Banas Kantha, Patan, Sabar Kantha Paschim Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Rajkot, Porbandar, Junagadh, (PGVCL) Rajkot Jamnagar, Kutch, Bhavnagar, Amreli, Surendranagar Dakshin Gujarat Vij Company Ltd. Surat except city, Bharuch, (DGVCL) Surat Narmada, Dang,Valsad, Navsari Processing and releasing Authority of HT connection UP TO CIRCLE 275 KVA OFFICE Above CORPORATE 275 KVA OFFICE Procedure for Registration of Application for HT Power Supply Application for supply of power shall be made in the prescribed form. The requisition for supply of electrical energy shall be accompanied by registration charges as under. HT and EHT supply @ Rs.10 per KVA with a ceiling of Rs.25000.00 Checklist- Submission of Documents for Power Supply • Prescribed Application Form in Four (4) Copies • Site plan with key map indicating point of supply in Four (4) Copies. • Land documents – Plot Allotment letter OR 7/12 and 8A Abstract, OR Sale deed in Two (2) Copies. • Memorandum of Articles • Resolution authorizing the person(s) to sign Application and Agreement • Short Description of process • Certificate regarding Industrial use of land from Collector (Before work is taken up on hand.) • NOC of Gujarat Pollution Control Board (Before actual release of power supply.) Estimate [1] • On registration of demand, the DISCOM shall furnish an estimate including Security Deposit and charges for providing electric line/infrastructure as per technical feasibility report. -

Gujarat State

CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENEATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUNDWATER YEAR BOOK – 2018 - 19 GUJARAT STATE REGIONAL OFFICE DATA CENTRE CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD WEST CENTRAL REGION AHMEDABAD May - 2020 CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD MINISTRY OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT AND GANGA REJUVENEATION GOVERNMENT OF INDIA GROUNDWATER YEAR BOOK – 2018 -19 GUJARAT STATE Compiled by Dr.K.M.Nayak Astt Hydrogeologist REGIONAL OFFICE DATA CENTRE CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD WEST CENTRAL REGION AHMEDABAD May - 2020 i FOREWORD Central Ground Water Board, West Central Region, has been issuing Ground Water Year Book annually for Gujarat state by compiling the hydrogeological, hydrochemical and groundwater level data collected from the Groundwater Monitoring Wells established by the Board in Gujarat State. Monitoring of groundwater level and chemical quality furnish valuable information on the ground water regime characteristics of the different hydrogeological units moreover, analysis of these valuable data collected from existing observation wells during May, August, November and January in each ground water year (June to May) indicate the pattern of ground water movement, changes in recharge-discharge relationship, behavior of water level and qualitative & quantitative changes of ground water regime in time and space. It also helps in identifying and delineating areas prone to decline of water table and piezometric surface due to large scale withdrawal of ground water for industrial, agricultural and urban water supply requirement. Further water logging prone areas can also be identified with historical water level data analysis. This year book contains the data and analysis of ground water regime monitoring for the year 2018-19. -

List Fo Gram Panchayats

List fo Gram Panchayats - Phase I Name of District Name of Block Name of GP AMRELI LATHI ADATALA AMRELI LATHI AKALA AMRELI LATHI ALI UDEPUR AMRELI LATHI AMBARDI AMRELI LATHI ASODRA AMRELI LATHI BHALVA AMRELI LATHI BHATTVADAR AMRELI LATHI BHINGADH AMRELI LATHI BHURAKIA AMRELI LATHI CHAVANA AMRELI LATHI CHHBHADIA AMRELI LATHI DERDI JANBAI AMRELI LATHI DHAMEL AMRELI LATHI DHINTARA AMRELI LATHI DHRUFANIA AMRELI LATHI DUDALA(LATHI) AMRELI LATHI DUDHALA BAI AMRELI LATHI HAJIRADHAR HARSURPUR AMRELI LATHI DEVALYA+PUNJAPAR AMRELI LATHI HAVTED AMRELI LATHI HIRANA AMRELI LATHI INGORALA JAGAN AMRELI LATHI KANCHARDI AMRELI LATHI KARKOLIA AMRELI LATHI KERIYA AMRELI LATHI KERLA AMRELI LATHI KRISHNA GADH AMRELI LATHI LATHI BLOCK AMRELI LATHI LUVARIA AMRELI LATHI MALVIYA PIPARIYA AMRELI LATHI MATRILA AMRELI LATHI MULIPAT AMRELI LATHI NANA RAJKOT AMRELI LATHI NANA RAJKOT AMRELI LATHI NANAKANKOT AMRELI LATHI NARANGADH+MEMDA AMRELI LATHI PADAR SINGHA AMRELI LATHI PIPALAVA AMRELI LATHI PRATAPGADH AMRELI LATHI RABDHA AMRELI LATHI RAMPUR AMRELI LATHI SAKHPUR AMRELI LATHI SEKHPIPARIA AMRELI LATHI SUVAGADH AMRELI LATHI TAJPAR AMRELI LATHI THANSA AMRELI LATHI TODA AMRELI LATHI VIRPUR AMRELI LATHI ZARAKIA AMRELI AMRELI AMRELI BLOCK AMRELI AMRELI BARVALA BAVISHI AMRELI AMRELI BOXIPUR AMRELI AMRELI CHAKHAV JADH AMRELI AMRELI CHANDGADH AMRELI AMRELI CHAPTHAL AMRELI AMRELI CHIYADIYA AMRELI AMRELI DAHIR AMRELI AMRELI DEBALIYA AMRELI AMRELI DEVARAJIA AMRELI AMRELI DURAJA AMRELI AMRELI FATENPUR AMRELI AMRELI GAVDAGA AMRELI AMRELI GIRIYA AMRELI AMRELI HARIPUR AMRELI AMRELI -

ITI PALANPUR Date of Exam 15/11/2008

GUJARAT COUNCIL OF VOCATIONAL TRAINING 3rd floor, Block No. 8, Dr. Jivraj Mehta Bhavan Ghandhinagar Name of Exam 901 - Course on Computer Concept (CCC) Page no : 1 Center Name : 106 - ITI PALANPUR Date of Exam 15/11/2008 Candidate Name and Designation Practical / Seat No Result Department Theory Marks Training Period Direct Exam 1 HARIJAN KAMABHAI PABABHAI Sr.No Ab 0 ASSISTANT TEACHER 081190110646024 Ab Absent CHALA PRIMARY SCHOOL,CHALA 2 PATEL BHAVANABEN NARGIBHAI Sr.No 20 46 ASSISTANT TEACHER 081190110646025 26 Fail SHREE VASDA PRIAMRY SCHOOL 3 KHADIYA CHALAKDAN HARISINHJI Sr.No Ab 0 ASSISTANT TEACHER 081190144106001 Ab Absent BRAHMANVAS PRIMARY SCHOOL,SUIGAM 4 JOSHI BHARATKUMAR RAMESHCHANDRA Sr.No 28 58 ASSISTANT TEACHER 081190144106002 30 Pass MONTA PRIMARY SCHOOL 5 NAYAK HASMUKHBHAI KESHAVLAL Sr.No Ab 0 PRIMARY TEACHER 081190144106003 Ab Absent CHHAPI PAY CENTER PRIMARY SCHOOL 6 PATEL SANKARBHAI AMBALAL Sr.No Ab 0 CRAFT TEACHER 081190144106004 Ab Absent SHREE C.K.MEHTA COLLEGE OF PRIMARY EDUCATION 7 SOLANKI RAYCHANDJI MERUJI Sr.No 25 57 ASSISTANT TEACHER 081190144106005 32 Pass MONTA PRIMARY SCHOOL 8 PRAJAPATI PARSOTTAMBHAI MEGHABHAI Sr.No 28 42 ASSISTANT TEACHER 081190144106006 14 Fail MANKA PRIMARY SCHOOL 9 MODI NITABEN CHIMANLAL Sr.No 25 25 TEACHER 081190144106007 0 Fail CHHAPI PAY CENTER SCHOOL 10 SENGAL KHODIDAS KHUSALDAS Sr.No Ab 0 HEAD MASTER 081190144106008 Ab Absent MANKA PRIMARY SCHOOL 11 SONI HETALBEN SHANTILAL Sr.No 22 37 PRIMARY TEACHER 081190144106009 15 Fail SANGLA PRIMARY SCHOOL 12 PATEL SHARADABEN RAMJIBHAI Sr.No 18 19 PRIMARY TEACHER 081190144106010 1 Fail BHARKAWADA PRIMARY SCHOOL GUJARAT COUNCIL OF VOCATIONAL TRAINING 3rd floor, Block No.