Sacred Music Volume 124 Number 3

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Profane Choral Compositions of Lorenzo Perosi

THE PROFANE CHORAL COMPOSITIONS OF LORENZO PEROSI By KEVIN TODD PADWORSKI B.A., Eastern University, 2008 M.M., University of Denver, 2013 A TMUS Project submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University of Colorado in partial fulfillment Of the requirement for the degree of Doctor of Musical Arts College of Music 2019 1 THE PROFANE CHORAL COMPOSITIONS OF LORENZO PEROSI By KEVIN TODD PADWORSKI Approved APRIL 8, 2019 ___________________________________________ Dr. Elizabeth Swanson Associate Director of Choral Studies and Assistant Professor of Music __________________________________________ Dr. Yonatan Malin Associate Professor of Music Theory __________________________________________ Dr. Steven Bruns Associate Dean for Graduate Studies; Associate Professor of Music Theory 2 Table of Contents Title Page Committee Approvals 1 Table of Contents 2 Abstract 3 Introduction 4 Biography 6 Profane Choral Compositions 23 Conclusion 32 Appendices 33 Appendix I: Complete List of the Profane Compositions Appendix II: Poetic Texts of Selected Profane Compositions Bibliography 36 3 Abstract The vocal music created in Italy during the late 1800s and early 1900s is often considered to be the height of European vocal art forms, and the era when the operatic and choral genres broke their way into mainstream appreciation. One specific composer’s career was paramount to the rise of this movement: Monsignor Don Lorenzo Perosi. At the turn of the twentieth century, his early premieres of choral oratorios and symphonic poems of massive scale thoroughly impressed notable musical colleagues worldwide and quickly received mass adoration and accolades. In addition to these large works, Perosi produced a prolific number of liturgical choral compositions that shaped the sound and style of choral music of the Roman Catholic Church for over half a century. -

Quadrivium Dir

Periodici dell'A.M.I.S. Quadrivium dir. responsabile Giuseppe Vecchi Qadrivium - Prima Serie VOL. I - FASC. I - 1956 B. M. Marti, Lucan's Invocation to Nero in the Light of the Mediaeval Commentaries. G. Vecchi, Il "planctus" di Gudino di Luxeuil: un ambiente scolastico, un ritmo, una melodia. V. Pini, La Summa de vitiis et virtutibus di Guido Faba. G. Vecchi, Sulla composizione del Pomerium di Marchetto da Padova e la Brevis Compilatio. VOL. I - FASC. 2 - 1956 A. Saiani, L'"Astrologia spiritualis" neIl'Epithalamium e nella Stella Maris di Giovanni di Garlandia. G. Vecchi, Modi d'arte poetica in Giovanni di Garlandia e il ritmo Aula vernat virginalis. E. Franceschini, Ricerche e risultati per la storia dell' Organon aristotelico nell'occidente latino. G. Massera, Un sistema teorico di notazione mensurale nell'esercitazione di un musico del '400. VOL. II - 1958 J. Carmody, The Arabic Corpus of Greek Astronomer and Mathematicians. E. Jammers, Der Vortrag des lateinischen Hexameters im Frühen Mittelalter. G. Maillard, Problèmes musicaux et littéraires du Lai. G. Cattin, Contributi alla storia della lauda spirituale. Sulla evoluzione musicale e letteraria della lauda nei secoli XlV e XV. W. Dürr, Zwei neue Belege fur die sogenannte "spielmännische" Reduction. VOL. III - 1959 L. Gherardi, Il Codice Angelica 123 monumento della Chiesa Bologuese nel sec. XI. VOL. IV - 1960 G. Cattin, Il manoscritto Venet. marc. Ital. IX, 145. G. Vecchi, Le Arenge di Guido Faba e l'eloquenza d’arte, civile e politica duecentesca. F. Haberl, I modelli gregoriani e il loro sviluppo nei canti dell’attuale messa romana. VOL. -

Historical Perspective on Change & Growth in the Church

Historical Perspective on Change & Growth in the Church Don’t know much about history…. We are a historical people. God chose a people to make His own and from which would come a Savior. The Church was born not only out of the Jewish world of Pentecost but also out of the Greco-Roman world which believed that the Pax Romana was the final chapter. We, the Church, have been given the call to reveal the true Kingdom of Peace to a world still confident in its own power. The History of the Liturgy is the only way to glimpse the power of that Kingdom alive in each epoch, including our own. Jewish Roots—Meal and Word Passover and Seder Elements o Berakoth—classic blessings for food, land and Jerusalem o Todah—an account of God’s works and a petition that the prayers of Israel be heard o Tefillah—great intercessions o Kiddush—Holy is God o Haggadah—great narrative of salvation o Hallel—Psalms 113-118 recited at Passover Synagogue Elements o Readings from Torah, Prophets and Wisdom o Teachings o Singing of Cantor, mainly psalms Early Greco-Roman Elements—from home meal to House Church Paul and problem of agape in I Cor 11, from the 50’s o Divisions among you o Every one in haste to eat their supper, one goes hungry while another gets drunk o Institution Narrative o Whoever eats or drinks unworthily sins against the body and blood of the Lord o One should examine himself first, then eat and drink o Whoever eats or drinks without recognizing the body eats and drinks a judgment on himself o That is why so many are sick and dying o Therefore when -

The Mediation of the Church in Some Pontifical Documents Francis X

THE MEDIATION OF THE CHURCH IN SOME PONTIFICAL DOCUMENTS FRANCIS X. LAWLOR, SJ. Weston College N His recent encyclical letter, Hurnani generis, of Aug. 12, 1950, the I Holy Father reproves those who "reduce to a meaningless formula the necessity of belonging to the true Church in order to achieve eternal salvation."1 In the light of the Pope's insistence in the same encyclical letter on the ordinary, day-by-day teaching office of the Roman Pontiffs, it will be useful to select from the infra-infallible but authentic teaching of the Popes some of the abundant material touching the question of the mediatorial function of the Church in the order of salvation. The Popes, to be sure, do not speak and write after the manner of theo logians but as pastors of souls, and it is doubtless not always easy to transpose to a theological level what is contained in a pastoral docu ment and expressed in a pastoral method of approach. Yet the authentic teaching of the Popes is both a guide to, and a source of, theological thinking. The documents cited are of varying solemnity and doctrinal importance; an encyclical letter is clearly of greater magisterial value than, let us say, an occasional epistle to some prelate. It is not possible here to situate each citation in its documentary context; but the force and point of a quotation, removed from its documentary perspective, is perhaps as often lessened as augmented. Those who wish may read them in their context, if they desire a more careful appraisal of evidence. -

Comentarios De Un Fiel a La Instrucción Universae Ecclesiae.Jlf

COMENTARIOS DE UN FIEL A LA INSTRUCCIÓN UNIVERSAE ECCLESIAE por JLF (Una Voce Sevilla) Misa Pontifical según el Usus Antiquior en la Cátedra de San Pedro. Roma 15/05/11 La Instrucción Universae Ecclesiae de la Pontificia Comisión Ecclesia Dei, de 30 de abril del año del Señor de 2011 –memoria de san Pio V según el Misal de Pablo VI-, publicada el 13 de mayo –festividad de la aparición de la Virgen de Fátima-, sobre la aplicación de la carta apostólica motu proprio data Summorum Pontificum del Sumo Pontífice Benedicto XVI, del 7 de julio de 2007, empieza en su introducción afirmando que el motu proprio ha hecho más accesible a la Iglesia universal –universae Ecclesia- la riqueza de la Liturgia romana, destacando con ello la finalidad principal y logros obtenidos por el documento papal hasta el día de hoy. 1 Además recuerda la Instrucción que con dicho motu proprio el Vicario de Cristo ha promulgado una ley universal para la Iglesia –universae Ecclesiae-, con la que ha tenido la intención de dar una nueva reglamentación para el uso de la Liturgia romana vigente en 1962, reafirmando con ello el principio de deber de cuidado de la Sagrada Liturgia y aprobación de los libros litúrgicos que tienen los papas. Y que Summorum Pontificum constituye una relevante expresión del magisterio del Romano Pontífice y del munus –potestad- que le es propio, es decir, regular y ordenar la Sagrada Liturgia de la Iglesia y manifiesta su preocupación como Vicario de Cristo y Pastor de la Iglesia Universal. El texto de la Comisión vaticana vuelve a dejar claro lo afirmado por Benedicto XVI en la mencionada carta apostólica1, que los textos del Misal Romano de Pablo VI y del reeditado por última vez por Juan XXVIII, son dos formas de la Liturgia Romana, definidas respectivamente como ordinaria y extraordinaria: son dos usos únicos del único Rito Romano, que se colocan uno al lado del otro –no existiendo superioridad de uno sobre otro-. -

MIC|MIC DG-BI SERV II|10/06/2021|0013699-P - Allegato Utente 1 (A01)

MIC|MIC_DG-BI_SERV II|10/06/2021|0013699-P - Allegato Utente 1 (A01) ENTI AMMESSI AI SENSI DELL'ART. 1, COMMA 1, Lett. A) e B) DEL D.P.C.M. 16 APRILE 2021 DENOMINAZIONE C.F. ENTE Indirizzo Comune Prov. CAP A LUNA & O SOLE 05378881212 Via Carlo Cattaneo 26 Napoli NA 80128 A. C. Balletto di Firenze 05638360486 Firenze Firenze FI 50134 A. Casasole di Orvieto 01537310557 Via Roma, 3 Orvieto TR 05018 A.A.Jonico Salentina A.P.S. 04756830750 Viale Regina Margherita 249 Taviano LE 73057 A.C. Mandala Dance Company 97677060580 Via Nevada n° 5 Ladispoli RM 00055 A.C.T. Compagnia dei Giovani 02130910223 Via della Malpensada 26 Trento TN 38123 A.C.T.I. Teatro Indipendente 07379320018 via San Pietro in Vincoli 28 Torino to 10152 a.d.a. associazione per la didattica el'ambiente onlus 05678671008 via gen. Roberto Bencivenga 50 a ROMA RM 00141 A.GE. ASSOCIAZIONE GENITORI PESARO ODV 92024130418 VIA VITTORIO VENETO N. 2 PESARO PU 61121 A.GI.MUS. Associazione Giovanile Musicale 96385310584 V.le delle Milizie 58 ROMA RM 00192 A.Lib.I. associazione culturale 90039770756 Via Di Vittorio 20 Tricase LE 73039 A.M.A. Calabria 82050390796 VIA P. CELLI, 23 LAMEZIA TERME CZ 88046 A.M.M.I. ASSOCIAZIONE MOGLI MEDICI ITALIANI 94016770714 CORSO MANFREDI 307 MANFREDONIA FG 71043 A.N.L.A. ONLUS 80031930581 Via val Cannuta 182 Roma RM 00166 A.P.S Coro Santa Cecilia - Musicultura 03473100273 Via Venanzio 3 Portogruaro VE 30026 A.P.S PORTLAND 01886360229 VIA PAPIRIA 8 Trento TN 38122 A.P.S. -

Religious Education Programme

Commitment and Ministry LEARNING STRAND: HUMAN EXPERIENCE RELIGIOUS EDUCATION PROGRAMME FOR CATHOLIC SECONDARY SCHOOLS IN AOTEAROA NEW ZEALAND 12H THE LOGO The logo is an attempt to express Faith as an inward and outward journey. This faith journey takes us into our own hearts, into the heart of the world and into the heart of Christ who is God’s love revealed. In Christ, God transforms our lives. We can respond to his love for us by reaching out and loving one another. The circle represents our world. White, the colour of light, represents God. Red is for the suffering of Christ. Red also represents the Holy Spirit. Yellow represents the risen Christ. The direction of the lines is inwards except for the cross, which stretches outwards. Our lives are embedded in and dependent upon our environment (green and blue) and our cultures (patterns and textures). Mary, the Mother of Jesus Christ, is represented by the blue and white pattern. The blue also represents the Pacific… Annette Hanrahan RSCJ Commitment and Ministry GETTY IMAGES LEARNING STRAND: SACRAMENT AND WORSHIP 12H © 2014 National Centre for Religious Studies First published 1991 No part of this document may be reproduced in any way, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted by any means, without the prior permission of the publishers. Imprimatur + Colin Campbell DD Bishop of Dunedin Conference Deputy for National Centre for Religious Studies October 2007 Authorised by the New Zealand Catholic Bishops’ Conference. Design & Layout: Devine Graphics PO Box 5954 Dunedin New Zealand Published By: National Centre for Religious Studies Catholic Centre PO Box 1937 Wellington New Zealand Printed By: Printlink 33–43 Jackson Street Petone Private Bag 39996 Wellington Mail Centre Lower Hutt 5045 Māori terms are italicised in the text. -

Mediator Dei

MEDIATOR DEI ENCYCLICAL OF POPE PIUS XII ON THE SACRED LITURGY TO THE VENERABLE BRETHREN, THE PATRIARCHS, PRIMATES, ARCHBISHOPS, BISHIOPS, AND OTHER ORDINARIES IN PEACE AND COMMUNION WITH THE APOSTOLIC SEE Venerable Brethren, Health and Apostolic Benediction. Mediator between God and men[1] and High Priest who has gone before us into heaven, Jesus the Son of God[2] quite clearly had one aim in view when He undertook the mission of mercy which was to endow mankind with the rich blessings of supernatural grace. Sin had disturbed the right relationship between man and his Creator; the Son of God would restore it. The children of Adam were wretched heirs to the infection of original sin; He would bring them back to their heavenly Father, the primal source and final destiny of all things. For this reason He was not content, while He dwelt with us on earth, merely to give notice that redemption had begun, and to proclaim the long-awaited Kingdom of God, but gave Himself besides in prayer and sacrifice to the task of saving souls, even to the point of offering Himself, as He hung from the cross, a Victim unspotted unto God, to purify our conscience of dead works, to serve the living God.[3] Thus happily were all men summoned back from the byways leading them down to ruin and disaster, to be set squarely once again upon the path that leads to God. Thanks to the shedding of the blood of the Immaculate Lamb, now each might set about the personal task of achieving his own sanctification, so rendering to God the glory due to Him. -

Maquette CDC Version Finale

Dossier de Préparation des Chefs de Chapitre 2014 « Au Commencement, Dieu créa le Ciel et la Terre » 32e Pèlerinage de Pentecôte de Notre-Dame de Paris à Notre-Dame de Chartres DOSSIER DE PREPARATION DES CHEFS DE CHAPITRE 2014 SOMMAIRE REMERCIEMENTS .......................................................................... 3 PRÉSENTATION DU DOSSIER DE PRÉPARATION ................. 4 CANEVAS & RECOMMANDATIONS ......................................... 10 MOT DE L’AUMÔNIER GÉNÉRAL ............................................ 13 1ERE PARTIE : MÉDITATIONS THÉMATIQUES ....................... 15 PLAN DES MÉDITATIONS THÉMATIQUES ------------------------------------- 15 SAINT THOMAS D’AQUIN ................................................................................ 17 LE MYSTERE DE DIEU .................................................................................... 22 LA CREATION DE L’HOMME ........................................................................... 29 POURQUOI L’HOMME DOIT-IL CONNAITRE DIEU ? ......................................... 35 SAINT FRANÇOIS D’ASSISE ............................................................................. 41 ORDRE DIVIN ET BEAUTE DE LA CREATION ...................................................... 46 L’HOMME FACE À LA CRÉATION : LE RESPECT QU’IL LUI DOIT ........................ 52 LE MAL ET LE DESORDRE OPPOSES A LA BEAUTE DE LA CREATION .................. 59 FOI ET RAISON ................................................................................................ 65 SAINT THOMAS -

John Rutter: Choral Ambassador

October 2017 Issue 56 Hemiola St George’s Singers JOHN RUTTER: CHORAL AMBASSADOR INSIDE THIS ISSUE: BY NEIL TAYLOR Rachmaninov Vespers 2 Chanting Russia’s history 3 To my mind, John Rutter is a He’s also a thoroughly engag- Verdi Requiem review 4 skilled craftsman, a gifted com- ing, warm and generous man. I Christmas with Rutter 5 poser and a classy interpreter. first met him when, as a student, I had a call one Saturday after- Letter from the Editor 5 Let’s look: a definitive version of noon asking if I could come and SGS News 6 the Fauré Requiem in its original make drinks at a Cambridge scoring; many brilliant record- Singers’ recording session in Kath Dibbs remembered 6 ings with his own group, The Robert Brooks: interview 7 Hampstead, North London. Everybody tells me, who has sung in a choir, I hopped on the tube, arrived Costa Rica: final memories 8 that they feel better for doing it. Whatever the Song for Diana 9 at University College cares of the day, if they meet after a School, listened to the ses- long day’s school or work, somehow Beethoven’s Fantasy 10 they leave their troubles at the door. sions with that amazing Carol concert and Messiah 11 group and the wonderful Jill White as producer, and Cambridge Singers over the past brewed up. 35 years; such an accomplished Since then, I’ve had the privi- eye and ear for instrumental and vocal colours; beautifully hand- lege of working with John and ST GEORGE’S SINGERS whilst he is charming and anec- written music notation; well- dotal, he does demand much of PRESIDENT: crafted melodies; skilled and apt use of texts; a brilliant interpreter his fellow musi- Choral music is not one of life’s frills. -

1 Celebrating Mass Alone an Introductory Note This Is Exactly

Celebrating Mass Alone An Introductory Note This is exactly NOT how the Mass should be celebrated. From its inception at the Last Supper (not taking its Old Testament background into consideration), it has always been a communal act. At present, with the Covid-19 Pandemic which has sent ripples of fear around; especially that of deadly contagion, the solemn community celebration of the Liturgy of the Roman Rite has to face a number of challenges. Touch has become taboo. Proximity is dreaded now. Distance, Isolation and total insulation has become the order of the day. Churches are closed in many places and community celebrations are a luxury. People are getting used to the liturgical anomalies and they are slowly becoming the norm. In the long run, these can lead to deformities, remedying which, would be an uphill task. From a purely Ministerial Priesthood perspective, priests are left with a serious spiritual concern. When community Mass is not possible, and when one is all by oneself, what would be the option? Celebrate Mass alone, or not celebrate at all, because Mass is essentially an act of the whole Mystical Body of Christ. An Outline of its History In the apostolic communities and thereafter, Mass was the Breaking of Bread by the community. Even after the 4th century it remained so for a long time. The first signs of isolation appeared with the transition of the language of the liturgy from Greek to Latin. The original quality of the Latin language used in the Roman Rite was more poetic and scholarly; and it required some effort to participate actively. -

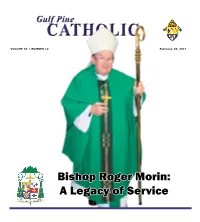

Bishop Roger Morin: a Legacy of Service 2 Most Reverend Roger P

Gulf Pine CATHOLIC VOLUME 34 / NUMBER 12 February 10, 2017 Bishop Roger Morin: A Legacy of Service 2 Most Reverend Roger P. Morin Third Bishop of Biloxi (2009 - 2016) Bishop Roger Paul Morin was Orleans. In 1973, he was appointed associate director of Bishop Morin received the Weiss Brotherhood Award installed as the third Bishop of Biloxi the Social Apostolate and in 1975 became the director, presented by the National Conference of Christians and on April 27, 2009, at the Cathedral of responsible for the operation of nine year-round social Jews for his service in the field of human relations. the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin service centers sponsored by the archdiocese. Bishop Bishop Morin was a member of the USCCB’s Mary by the late Archbishop Pietro Morin holds a master of science degree in urban studies Subcommittee on the Catholic Campaign for Human February 10, 2017 • Bishop Morin Sambi, Apostolic Nuncio to the from Tulane University and completed a program in Development 2005-2013, and served as Chairman 2008- United States, and Archbishop 1974 as a community economic developer. He was in 2010. During that time, he also served as a member of Thomas J. Rodi, Metropolitan Archbishop of Mobile. residence at Incarnate Word Parish beginning in 1981 the Committee on Domestic Justice and Human A native of Dracut, Mass., he was born on March 7, and served as pastor there from 1988 through April 2002. Development and the Committee for National 1941, the son of Germain J. and Lillian E. Morin. He has Bishop Morin is the Founding President of Second Collections.