Namibian Islands' Marine Protected Area

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RUMOURS of RAIN: NAMIBIA's POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre Du Pisani

SOUTHERN AFRICAN ISSUES RUMOURS OF RAIN: NAMIBIA'S POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre du Pisani THE .^-y^Vr^w DIE SOUTH AFRICAN i^W*nVv\\ SUID AFRIKAANSE INSTITUTE OF f I \V\tf)) }) INSTITUUT VAN INTERNATIONAL ^^J£g^ INTERNASIONALE AFFAIRS ^*^~~ AANGELEENTHEDE SOUTHERN AFRICAN ISSUES NO 3 RUMOURS OF RAIN: NAMIBIA'S POST-INDEPENDENCE EXPERIENCE Andre du Pisani ISBN NO.: 0-908371-88-8 February 1991 Toe South African Institute of International Affairs Jan Smuts House P.O. Box 31596 Braamfontein 2017 Johannesburg South Africa CONTENTS PAGE INTRODUCTION 1 POUTICS IN AFRICA'S NEWEST STATE 2 National Reconciliation 2 Nation Building 4 Labour in Namibia 6 Education 8 The Local State 8 The Judiciary 9 Broadcasting 10 THE SOCIO-ECONOMIC REALM - AN UNBALANCED INHERITANCE 12 Mining 18 Energy 19 Construction 19 Fisheries 20 Agriculture and Land 22 Foreign Exchange 23 FOREIGN RELATIONS - NAMIBIA AND THE WORLD 24 CONCLUSIONS 35 REFERENCES 38 BIBLIOGRAPHY 40 ANNEXURES I - 5 and MAP 44 INTRODUCTION Namibia's accession to independence on 21 March 1990 was an uplifting event, not only for the people of that country, but for the Southern African region as a whole. Independence brought to an end one of the most intractable and wasteful conflicts in the region. With independence, the people of Namibia not only gained political freedom, but set out on the challenging task of building a nation and defining their relations with the world. From the perspective of mediation, the role of the international community in bringing about Namibia's independence in general, and that of the United Nations in particular, was of a deep structural nature. -

CROWNED CORMORANT | Microcarbo Coronatus (Phalacrocorax Coronatus)

CROWNED CORMORANT | Microcarbo coronatus (Phalacrocorax coronatus) J Kemper | Reviewed by: T Cook; AJ Williams © Jessica Kemper Conservation Status: Near Threatened Southern African Range: Coastal Namibia, South Africa Area of Occupancy: 6,700 km2 Population Estimate: 1,200 breeding pairs in Namibia Population Trend: Stable to slightly increasing Habitat: Coastal islands and rocks, protected mainland sites, artificial structures, inshore marine waters Threats: Disturbance, entanglement in human debris and artificial structures, predation by gulls and seals, pollution from oiling 152 BIRDS TO WATCH IN NAMIBIA DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE TABLE 2.5: A resident species with some juvenile dispersal, this small Number of Crowned Cormorant breeding pairs at individu- cormorant is endemic to south-west Namibia and west al breeding localities in Namibia (listed north to south), esti- to south-western South Africa. It has a very restricted mated from annual peaks of monthly nest counts at Mercu- ry, Ichaboe, Halifax and Possession islands, and elsewhere range along the coastline (Crawford 1997b), occupying an from opportunistic counts, not necessarily done during peak area of about 6,700 km2 in Namibia (Jarvis et al. 2001). It breeding (Bartlett et al. 2003, du Toit et al. 2003, Kemper et usually occurs within one kilometre of the coast, and has al. 2007, MFMR unpubl. data). not been recorded more than 10 km from land (Siegfried et al. 1975). It breeds at numerous localities in Namibia Number of Date of most and South Africa. In Namibia, it is known to breed at 12 breeding recent reliable islands, five mainland localities and one artificial structure, Breeding locality pairs estimate from Bird Rock Guano Platform near Walvis Bay to Sinclair Bird Rock Platform 98 1999/2000 Island (Table 2.5: Bartlett et al. -

The German Colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German Rivalry, 1883-1915

University of Nebraska at Omaha DigitalCommons@UNO Student Work 7-1-1995 Doors left open then slammed shut: The German colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German rivalry, 1883-1915 Matthew Erin Plowman University of Nebraska at Omaha Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork Recommended Citation Plowman, Matthew Erin, "Doors left open then slammed shut: The German colonization of Southwest Africa and the Anglo-German rivalry, 1883-1915" (1995). Student Work. 435. https://digitalcommons.unomaha.edu/studentwork/435 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UNO. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Work by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UNO. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DOORS LEFT OPEN THEN SLAMMED SHUT: THE GERMAN COLONIZATION OF SOUTHWEST AFRICA AND THE ANGLO-GERMAN RIVALRY, 1883-1915. A Thesis Presented to the Department of History and the Faculty of the Graduate College University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts University of Nebraska at Omaha by Matthew Erin Plowman July 1995 UMI Number: EP73073 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI Blsaartalibn Publish*rig UMI EP73073 Published by ProQuest LLC (2015). Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. -

KELP BLUE NAMIBIA (Pty) Ltd

KELP BLUE NAMIBIA (Pty) Ltd EIA SCOPING & IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE PROPOSED KELP CULTIVATION PILOT PROJECT NEAR LÜDERITZ, KARAS REGION Prepared for: Kelp Blue Namibia (Pty) Ltd August 2020 1 DOCUMENT CONTROL Report Title EIA SCOPING & IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE PROPOSED KELP CULTIVATION PILOT PROJECT NEAR LÜDERITZ, KARAS REGION Report Author Werner Petrick Client Kelp Blue Namibia (Pty) Ltd Project Number NSP2020KB01 Report Number 1 Status Final to MEFT and MFMR Issue Date August 2020 DISCLAIMER The views expressed in the document are the objective, independent views of the author with input from various Environmental and Social Experts (i.e. Specialists). Neither Werner Petrick nor Namisun Environmental Projects and Development (Namisun) have any business, personal, financial, or other interest in the proposed Project apart from fair remuneration for the work performed. The content of this report is based on the author’s best scientific and professional knowledge, input from the Environmental Specialists, as well as available information. Project information contained herein is based on the interpretation of data collected and data provided by the client, accepted in good faith as being accurate and valid. Namisun reserves the right to modify the report in any way deemed necessary should new, relevant, or previously unavailable or undisclosed information become available that could alter the assessment findings. This report must not be altered or added to without the prior written consent of the author. Project Nr: NSP2020KB01 EIA SCOPING & IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT AND EMP FOR August 2020 Report number: 1 THE PROPOSED KELP CULTIVATION PILOT PROJECT 2 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. -

471 Mari Ne Law Developments I N Namibia D. J. Devine Institute

Mari ne Law Developments i n Namibia D. J. Devine Institute of Marine Law, University of Cape Town, South Africa Introduction Namibia became an independent state on 21 March 1990. Though only three years have elapsed since independence, that period has witnessed a number of important legal developments in the marine sector. The Constitution of Namibia contains provisions which are important in a marine context. The legislature has been active, and four important Acts have been adopted. Finally, the High Court 2 of Namibia has given judgment in six marine law case. It is the intention of this article to describe these constitutional, legislative and judicial marine law developments. The topics covered include maritime zones and their borders, passage rights, ownership of marine resource, the fishery law applicable in the exclusive economic zone (EEZ), a new fisheries regime, forfeiture of vessels used in committing fishery offences, questions relating to third party rights in such vessels, and international co-operation in enforcing fishery laws. The Territory of the Republic of Namibia It is necessary at the outset to describe what the territory of Namibia is and also the former status of the constituent parts of that territory. The reason is that the distinction between the different parts of the territory now claimed by Namibia is relevant to some of the questions later discussed in this article. The Constitution of Namibia describes the national territory of Namibia as "including the enclave, harbour and port of Walvis Bay, as well as the off-shore islands of Namibia, and its southern boundary shall extend to the middle of the Orange river."3 1 Territorial Sea and Exclusive Economic Zone of Namibia Act 3 of 1990:Territorial Sea and Exclusive Economic Zone of Namibia Amendment Act 30 of 1991;Marine Traffic Amendment Act 15 of 1991;Sea Fisheries Act 29 of 1992. -

Federal Register/Vol. 75, No. 187/Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 187 / Tuesday, September 28, 2010 / Rules and Regulations 59645 * Elevation in feet (NGVD) + Elevation in feet (NAVD) Flooding source(s) Location of referenced elevation # Depth in feet Communities above ground affected ∧ Elevation in meters (MSL) Modified Unnamed Tributary No. 1 to At the area bounded by U.S. Route 33, Wabash Avenue, +1415 Unincorporated Areas of Fink Run (Backwater effects and County Route 33/1. Upshur County. from Buckhannon River). * National Geodetic Vertical Datum. + North American Vertical Datum. # Depth in feet above ground. ∧ Mean Sea Level, rounded to the nearest 0.1 meter. ADDRESSES Unincorporated Areas of Upshur County Maps are available for inspection at the Upshur County Courthouse Annex, 38 West Main Street, Buckhannon, WV 26201. (Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance No. 76.913(b)(1)—62 FR 6495, February 12, collection requirements that are subject 97.022, ‘‘Flood Insurance.’’) 1997. to OMB approval. Dated: September 21, 2010. 76.924(e)(1)(iii) and (e)(2)(iii)—61 FR [FR Doc. 2010–24203 Filed 9–27–10; 8:45 am] Edward L. Connor, 9367, March 8, 1996. BILLING CODE 6712–01–P Acting Federal Insurance and Mitigation 76.925—60 FR 52119, October 5, 1995. Administrator, Department of Homeland 76.942(f)—60 FR 52120, October 5, Security, Federal Emergency Management 1995. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Agency. 76.944(c)—60 FR 52121, October 5, [FR Doc. 2010–24326 Filed 9–27–10; 8:45 am] 1995. Fish and Wildlife Service BILLING CODE 9110–12–P 76.957—60 FR 52121, October 5, 1995. -

Penguin Camp)

Appendix 1.2 PENGUIN Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (PENGUIN CAMP) Report from a Workshop held 8-9 September 1996, Cape Town, South Africa Edited by Susie Ellis, John P. Croxall and John Cooper Data sheet for the African Penguin Spheniscus demersus African Penguin Spheniscus demersus STATUS: New UCN Category: Vulnerable Based on: A1a, A2b, E CITES: Appendix II OTHER: In South Africa, endangered in terms of the Nature and Environmental Conservation Ordinance, No. 19 of 1974 of the Province of the Cape of Good Hope. This now applies to the Northern Cape, Western Cape and Eastern Cape Provinces. In Namibia, there is no official legal status. Listed as Near Threatened in Birds to Watch 2 (Collar et al. 1994). Listed as Vulnerable in the Red Data Book for South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland (Crawford 2000). Listed in Appendix II of the Convention for the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (Bonn Convention). Taxonomic status: Species. Current distribution (breeding and wintering): Breeding distribution: Between Hollams Bird Island, Namibia and Bird Island, Algoa Bay, South Africa. Number of locations: 27 extant breeding colonies - eight islands and one mainland site along the coast of southern Namibia; 10 islands and two mainland sites along the coast of Western Cape Province, South Africa; six islands in Algoa Bay, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa (Crawford et al. 1995a). There is no breeding along the coast of South Africa's Northern Cape Province, which lies between Namibia and Western Cape Province. Concentrated Migration Regions: None. Juveniles tend to disperse along the coastline to the west and north (Randall et al. -

Walvis Bay: South Africa's Claims to Sovereignty

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 16 Number 2 Winter/Spring Article 4 May 2020 Walvis Bay: South Africa's Claims to Sovereignty Earle A. Partington Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Earle A. Partington, Walvis Bay: South Africa's Claims to Sovereignty, 16 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 247 (1988). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. Walvis Bay: South Africa's Claims to Sovereignty EARLE A. PARTINGTON* I. INTRODUCTION After more than a century of colonial domination, the Mandated Territory of South West Africa/Namibia' is close to receiving-its indepen- dence. South Africa continues to administer the Territory as it has since its military forces conquered and occupied it in 1915 during World War I. In the negotiations between South Africa and the United Nations over Namibian independence, differences have arisen between the parties over whether the Territory includes either (1) the port and settlement of Walvis Bay, an enclave of 1124 square kilometers in the center of Namibia's Atlantic coast, or (2) the Penguin Islands, twelve small guano islands strung along 400 kilometers of the Namibian coast between Walvis Bay and the Orange River, the Orange River being part of the boundary between South Africa and Namibia. -

Partitioning of Nesting Space Among Seabirds of the Benguela Upwelling Region

PARTITIONING OF NESTING SPACE AMONG SEABIRDS OF THE BENGUELA UPWELLING REGION DAviD C. DuFFY & GRAEME D. LA CocK Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, South Africa, 7700. Received February /985 SUMMARY DuFFY, D. C. & LA CocK, G. D. 1985. Partitioning of nesting space among seabirds of the Benguela upwel ling region. Ostrich 56: 186-201. An examination of nesting habitats used by the four main species of seabirds nesting on southern African islands (Jackass Penguin Spheniscus demersus, Cape Cormorant Phalacrocorax capensis, Bank Cormorant P. neglectus and Cape Gannet Morus capensis) revealed relatively minor differences and extensive over laps between species, primarily in subcolony size, steepness of nesting substratum, and proximity to cliffs. A weak dominance hierarchy existed; gannets could displace penguins, and penguins could displace cor morants. This hierarchy appeared to have little effect on partitioning of nesting space. Species successfully defended occupied sites in most cases of interspecific conflict, suggesting that site tenure by one species could prevent nesting by another. The creation of additional nesting space on Namibian nesting platforms did not increase guano harvests, suggesting that nesting space had not previously limited the total nesting population of Cape Cormorants, the most abundant of the breeding species, in Namibia. While local shortages of nesting space may occur, populations of the four principal species of nesting seabirds in the Benguela upwelling region do not seem to have been limited by the availability of nesting space on islands. INTRODUCTION pean settlement, space for nesting was limited. Af ter settlement, human disturbance such as hunting The breeding seabirds of the Benguela upwel and guano extraction reduced nesting space, re ling region off Namibia and South Africa are be sulting in smaller populations of nesting seabirds. -

Implementation Status & Results

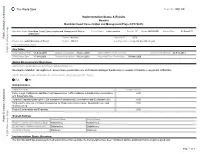

The World Bank Report No: ISR11851 Implementation Status & Results Namibia Namibian Coast Conservation and Management Project (P070885) Operation Name: Namibian Coast Conservation and Management Project Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 17 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 24-Sep-2013 (P070885) Public Disclosure Authorized Country: Namibia Approval FY: 2006 Product Line:Global Environment Project Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Sep-2005 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2015 Planned Mid Term Review Date Last Archived ISR Date 27-Feb-2013 Effectiveness Date 17-Oct-2005 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2015 Actual Mid Term Review Date 09-Mar-2009 Global Environmental Objectives Global Environmental Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) Development/Global: Strengthened conservation, sustainable use and mainstreaming of biodiversity in coastal and marine ecosystems in Namibia Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Policy, Legal, Institutional and Planning Framework for ICZM conducive to Biodiversity Conservation 0.00 and Sustainable Use Targeted Capacity-Building for ICZM conducive to Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Use 0.00 Targeted Investments in Critical Ecosystems for Biodiversity Conservation, Sustainable Use and 0.00 Mainstreaming Project Coordination and Reporting 0.00 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Public Disclosure Authorized Progress towards achievement of GEO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Moderate Moderate Public Disclosure Copy Implementation Status Overview The first NACOMA has always performed well and the activities under the first operation have been concluded and the additional finance is up to a good start. -

A Reader in Namibian Politics

State, Society and Democracy A Reader in Namibian Politics Edited by Christiaan Keulder Macmillan Education Namibia Publication of this book was made possible by the generous support of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. The views expressed by the authors are not necessarily the views of the Konrad-Adenauer-Stiftung. Konrad Adenauer Stiftung P.O.Box 1145, Windhoek Namibia Tel: +264 61 225568 Fax: +264 61 225678 www.kas.de/namibia © Konrad Adenauer Stiftung & individual authors, 2010 All rights reserved. No reproduction, copy or transmission of this publication may be made without written permission. No paragraph of this publication may be reproduced, copied or transmitted save with written permission. Any person who does any unauthorised act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages. Language editing by Sandie Fitchat Cover image by Melody Futter First published 2000 Reprinted 2010 Macmillan Education Namibia (Pty) Ltd P O Box 22830 Windhoek Namibia ISBN 978 99916 0265 3 Printed by John Meinert Printing, Windhoek, Namibia State, Society and Democracy Contents Acknowledgements ........................................................................................ vii List of Contributors ...................................................................................... viii List of Abbreviations ........................................................................................ix Introduction Christiaan Keulder ..............................................................................................1 -

“Stinky and Smelly – but Profitable”: the Cape Guano

“STINKY AND SMELLY – BUT PROFITABLE”: THE CAPE GUANO TRADE, c.1843 – 1910 HENDRIK SNYDERS DISSERTATION PRESENTED FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY (HISTORY) IN THE FACULTY OF ARTS AND SOCIAL SCIENCES AT STELLENBOSCH UNIVERSITY PROMOTOR: PROFESSOR SANDRA S. SWART CO-PROMOTOR: PROFESSOR ALBERT. M. GRUNDLINGH DECEMBER 2011 1 University of Stellenbosch http://scholar.sun.ac.za DECLARATION By submitting this dissertation electronically, I declare that the entirety of the work contained therein is my own, original work, that I am the sole author thereof (save to the extent explicitly otherwise stated), that reproduction and publication thereof by Stellenbosch University will not infringe any third party rights and that I have not previously in its entirety or in part submitted it for obtaining any qualifications. SIGNATURE:……………………………….. DATE:………………………………………… Copyright©2011 Stellenbosch University All rights reserved 2 University of Stellenbosch http://scholar.sun.ac.za ABSTRACT Soil infertility and concomitant low levels of food security under conditions of population pressure and land scarcity have been, and still remain, one of society’s most daunting challenges. Over time, societies have tried to maximize the yield from the available land through the use of various fertilisers. In the 19th century in the midst of an environment infertility crisis, guano (bird dung) from the Peruvian coastal islands became, through a combination of factors, the international fertilizer of choice for most commercial farmers. As a result, a combination of natural factors, monopoly control and price manipulation contributed to the relative scarcity of the product. Nevertheless, strategic manoeuvring between the major players prevented any significant change in the supply regime.