Public Response to Suicide News Reports As Reflected in Computerized Text Analysis of Online Reader Comments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Suicide Prevention and Postvention Toolkit for Texas Communities

Coming Together to Care Together Coming gethe To r t g o n i C a m r o e C A Suicide Prevention and Postvention Toolkit for Texas Communities Texas Suicide Prevention Council Texas Youth Suicide Prevention Project Virtual Hope Box App (coming soon) The Virtual Hope Box app will provide an electronic version of the Hope Box concept: a place to store important images, notes, memories, and resources to promote mental wellness. The app will be free for teens and young adults, and available for both Android and iPhone users. For up-to-date information on the Virtual Hope Box, please see: http://www.TexasSuicidePrevention.org or http://www.mhatexas.org. ASK & Prevent Suicide App (now available) ASK & Prevent Suicide is a suicide prevention smartphone app for Android and iPhone users. suicide, crisis line contact information, and other resources. To download this app, search “suicide preventionThis free app ASK” is filled in iTunes with oruseful Google information Play. about warning signs, guidance on how to ask about True Stories of Hope and Help (videos online now) A series of short videos featuring youth and young adults from Texas sharing their stories of hope and help. These are true stories of high school and college age students who have either reached out for help or referred a friend for help. These videos can be found at: http://www. TexasSuicidePrevention.org or on YouTube (http://www.youtube.com/user/mhatexas). FREE At-Risk Online Training for Public Schools and Colleges (now available) Watch for the middle school training scheduled for release in the fall of 2012. -

Healthcare Inspection

Department of Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General Healthcare Inspection Service Delivery and Follow-up After a Patient’s Suicide Attempt Minneapolis VA Health Care System Minneapolis, Minnesota Report No. 12-01760-230 July 19, 2012 VA Office of Inspector General Washington, DC 20420 To Report Suspected Wrongdoing in VA Programs and Operations: Telephone: 1-800-488-8244 E-Mail: [email protected] (Hotline Information: http://www.va.gov/oig/hotline/default.asp) Service Delivery and Follow-up After a Patient’s Suicide Attempt, Minneapolis VA HCS, Minneapolis, MN Executive Summary The VA Office of Inspector General Office of Healthcare Inspections conducted a review at the request of Congressman Tim Walz regarding alleged improper medication management and discharge planning practices at the Minneapolis VA Health Care System (the facility) in Minneapolis, MN. We did not substantiate the complainant’s allegations that a change in medication contributed to her husband’s death by suicide, that managers improperly tried to “commit” him to a Veterans Home, or that staff told her she was not her husband’s power of attorney (POA). Medical record documentation reflects that the patient’s medication had not been changed. His chronic depression was attributed to his medical and mental health conditions and to his substantial psychosocial stressors. Further, the medical record does not support the allegations related to the Veterans Home or POA. We found, however, that the Suicide Prevention Coordinator did not participate in the evaluation and ongoing monitoring of the patient, and the treatment team did not complete a suicide risk assessment at the time of the patient’s discharge in February. -

Preventing Suicide: a Global Imperative

PreventingPreventing suicidesuicide A globalglobal imperativeimperative PreventingPreventing suicidesuicide A globalglobal imperativeimperative WHO Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data Preventing suicide: a global imperative. 1.Suicide, Attempted. 2.Suicide - prevention and control. 3.Suicidal Ideation. 4.National Health Programs. I.World Health Organization. ISBN 978 92 4 156477 9 (NLM classification: HV 6545) © World Health Organization 2014 All rights reserved. Publications of the World Health Organization are The mention of specific companies or of certain manufacturers’ available on the WHO website (www.who.int) or can be purchased products does not imply that they are endorsed or recommended by from WHO Press, World Health Organization, 20 Avenue Appia, the World Health Organization in preference to others of a similar 1211 Geneva 27, Switzerland (tel.: +41 22 791 3264; fax: +41 22 791 nature that are not mentioned. Errors and omissions excepted, the 4857; e-mail: [email protected]). names of proprietary products are distinguished by initial capital letters. Requests for permission to reproduce or translate WHO publications –whether for sale or for non-commercial distribution– should be All reasonable precautions have been taken by the World Health addressed to WHO Press through the WHO website Organization to verify the information contained in this publication. (www.who.int/about/licensing/copyright_form/en/index.html). However, the published material is being distributed without warranty of any kind, either expressed or implied. The responsibility The designations employed and the presentation of the material in for the interpretation and use of the material lies with the reader. In this publication do not imply the expression of any opinion no event shall the World Health Organization be liable for damages whatsoever on the part of the World Health Organization concerning arising from its use. -

Crisis, Emergency, and Information Services Updated: 1/6/2020

Crisis, Emergency, and Information Services Updated: 1/6/2020 Emergency Crisis Response Call or Text 911 *Ask for CIT (crisis intervention trained) officer to help persons with mental disorders and/or addictions access medical treatment rather than place them in the criminal justice system due to illness related behaviors. Champaign County Crisis Line…………………………………………………………….……………….…. (217)-359-4141 24-hour suicide prevention and crisis hotline for the Champaign County, Illinois area. SASS (Screening, Assessment, and Support Services) ………………………………….......….…1-800-345-9049 A crisis mental health service program for children and adolescents, who are experiencing a psychiatric emergency. 2-1-1 United Way……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. 211 24-free phone line to help the public find needed services in the community. Website: www.unitedwayillinois.org/211/211.php and www.navigateresources.net/path/ American Red Cross………………………………………………………………………………………………………… (217)-351-5861 Location: 404 Ginger Bend Drive, Champaign. Services for those affected by natural disasters and single family fires. Website: www.redcrossillinois.org Child Abuse Hotline (DCFS)………………………………………………………………………………………….. 1-800-252-2873 24-hour hotline to report suspected child abuse/neglect. Crisis Nursery………………………………………………………………………………………………… (217)-337-2730 (crisis line) Location: 1309 W. Hill St., Urbana. Free 24-hour emergency child care for families with children, up to age 5. Staff speak Spanish. Website: www.crisisnursery.net DCFS – Illinois Department of Children and Family Services…………………………..…………….. (217)-278-5400 Location: 508 S. Race Street, Urbana Housing assistance, parent education, and family support. Disaster Distress Line…………………………………………………………………….………… 1-800-985-5990 or Text 66746 Spanish: 1-800-985-5990, press 2 Provides 24/7, 365-day-a-year crisis counseling and support to people experiencing emotional distress related to natural or human-caused disasters. -

Comments to FCC Secretary On

March 23, 2021 Marlene H. Dortch Secretary Federal Communication Commission 45 L Street NE Washington, DC 20554 Re: Ex Parte Docket No. 18-336; Docket No. 20-291; Docket No. 09-14 Dear Ms. Dortch, The undersigned organizations, all of whom support the development and implementation of the 988 national mental health and suicide crisis response system, are deeply appreciative of the Commission’s role in creating 988 and your current efforts to address fee diversion. The National Suicide Hotline Designation Act, unanimously passed by both chambers of Congress and signed into law last year, designates the collection and use of 911-like fees to support 988 call centers, crisis outreach, and stabilization—the continuum of crisis care needed to appropriately respond to callers in distress. 988 service fees, like 911 service fees, will provide a stable, continued source of funding for the hundreds of under-resourced local crisis call centers that will answer 988 calls in communities across the country. An effective 988 crisis response system has never been more necessary. Before the outset of COVID-19, nearly 1 in 5 people lived with a mental health condition and over 10 million people experienced thoughts of suicide. Recent reporting from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention indicate that mental health and suicidal ideation have worsened during the pandemic; approximately twice as many respondents reported serious thoughts of suicide and 40% of U.S. adults reported struggling with mental health or substance use. Present-day stressors can be particularly challenging for at-risk communities, with nearly 1 in 4 young people reporting suicidal thoughts. -

Certified Centers Addresses

Name of Center City State Zip Website 180 Turning Lives Around, 2nd Floor Haziet NJ 7735 www.180nj.org 2-1-1 Big Bend, Inc. Tallahassee FL 32302 www.211bigbend.org 211 Brevard Cocoa FL 32923-0417 www.211brevard.org 211 Broward Oakland Park FL 33334 www.211-broward.org 211 Palm Beach/Treasure Coast Lantana FL 33462 www.211palmbeach.org 2-1-1 Tampa Bay Cares Largo FL 33779 www.211tampabay.org Access Helpline Washington DC 20002 www.dbh.dc.gov/service/access-helpline ACTS/Helpline Manassas VA 22026 www.actspwc.org/acts-programs/helpline/ ADAPT Community Solutions Dallas TX 75207 www.adaptusa.com Alachua County Crisis Center Gainesville FL 32641 www.alachuacounty.us/crisis Austin Travis County Integral Care Austin TX 78764 www.atcic.org Avail Solutions Inc Corpus Christi, TX 78411 www.availsolutions.com Baltimore Crisis Response, Inc. Baltimore MD 21239 www.bcresponse.org Behavioral Health Response St. Louis MO 63141 www.bhrstl.org Boys Town National Hotline Omaha NE 68010 www.boystown.org Canadian Mental Health Association: Edmonton Region Edmonton AB Canada T5J 1G4 www.edmonton.cmha.ca Canandaigua Veterans Affairs Medical Center, National Veterans' Suicide Hotline Canandaigua NY 14424 www.canandaigua.va.gov Careline Crisis Intervention Fairbanks AK 99701 www.carelinealaska.com Casa Pacifica,Centers for Children & Families Camarillo CA 9012 www.casapacifica.org Cascade Centers, Inc Portland OR 97223 www.cascadecenters.com Center for Elderly Suicide Prevention & Grief Related Service(Institute of Aging) San Francisco CA 94118 http://www.programsforelderly.com/health-center-for-elderly-suicide-prevention.php -

California Mental Health Services Authority

COUNTY SNAPSHOT – KERN COUNTY CONTACTS Interview Participants: Jennifer Arnold Meghan Boaz Alvarez, M.S., MFT MHSA Coordinator Mental Health Unit Supervisor, Kern County Kern County Mental Health Department Crisis Hotline & Access Center P.O. Box 1000, Bakersfield, CA 93302 Kern County Mental Health Department 661.868.6813 P.O. Box 1000, Bakersfield, CA 93302 [email protected] 661.868.8007 [email protected] Primary/Behavioral Health Care Integration: Lisa Espinoza Jamie Garcia Patient Liaison between Kern Medical Center Administrator for Mental Health Recovery and Kern County Mental Health Department Support 661.326.2717 Kern County Mental Health Department [email protected] P.O. Box 1000, Bakersfield, CA 93302 661.868.5065 Public/Media Relations: [email protected] Kristie Curttright Press Liaison Suicide Prevention Activities: Kern County Mental Health Department Meghan Boaz Alvarez (see above) P.O. Box 1000, Bakersfield, CA 93302 661.868.6608 Ellen Eggert [email protected] Survivors of Suicide (SOS) P.O. Box 1000, Bakersfield, CA 93302 Student Mental Health Contact: 661.868.1552 Deanna Cloud [email protected] Mental Health Children’s Services Administrator Stigma & Discrimination Reduction Activities: Kern County Mental Health Department Jamie Garcia (see above) P.O. Box 1000, Bakersfield, CA 93302 661.868.6707 Patrice Mancini [email protected] President NAMI Kern County PO Box 9144, Bakersfield, CA 93389-9144 661.868.5061 www.namikerncounty.org [email protected] OVERVIEW Method of Data Collection Utilized: In-Person Interview December 13, 2011 Kern County, in California’s Central Valley, is the third largest county by area in the contiguous United States. -

Crisis Services Sheet

Resources in Behavioral Health Crisis Services Overviews of Crisis Services Expanding Behavioral Health Community-Based Crisis Response Systems: A Webinar Series http://wciconferences.com/2014-CRSwebinars/index.html Author: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. This is a series of six webinars on how to expand community-based crisis response services and systems. These webinars describe new and emerging crisis response practices across a continuum of need that includes pre-crisis planning, early intervention, crisis stabilization, and post-crisis support. In addition, the webinars explore the outcomes sought for different approaches and how these approaches are financed, and provides state and local examples. Crisis Services: Effectiveness, Cost-Effectiveness, and Funding Strategies http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4848/SMA14-4848.pdf Author: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2014. This report summarizes the current evidence base on the clinical effectiveness and cost- effectiveness of different types of crisis services. Case studies show different approaches being used by states to coordinate, consolidate, and blend funding sources to improve crisis services. Practice Guidelines: Core Elements in Responding to Mental Health Crises http://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA09-4427/SMA09-4427.pdf Author: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, 2009. The goal of these guidelines is to improve services for people with serious mental illness or emotional disorders who are in mental health crises. The guidelines define values, principles, and infrastructure to support appropriate responses to mental health crises for organizations ranging from hospitals and mental health clinics to schools and foster care. They can be used to help evaluate existing protocols or establish new ones. -

The Following Contains a List of Suicide Prevention Resources for St. Mary's

The following contains a list of suicide prevention resources for St. Mary’s County, Maryland teens—for those who may be at risk for suicide and those who have friends who may be at risk. These websites all have fact sheets, and some have videos, stories written by teens, and text and online chat options. CRISIS TEXT LINE Text “HOME” to 741741 Crisis Text Line is a text line that provides free emotional support and information to teens in crisis or go online at http://www.crisistextline.org/. Available 24/7. NATIONAL SUICIDE PREVENTION LIFELINE 1–800–273-TALK (8255) The Lifeline is a free phone line for people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress. An online chat option is available at http://www.suicidepreventionlifeline.org/GetHelp/LifelineChat.aspx. Available 24/7. MARYLAND YOUTH CRISIS HOTLINE 1-800-422-0009 Maryland Youth Crisis Hotline and Help4MDYouth.org are initiatives of the Maryland Crisis Hotline Network. Available 24/7, free of charge. ST. MARY’S COUNTY CRISIS HOTLINE 301-863-6661 This is a free 24/7 local hotline operated by Walden Behavioral Health, a private, non-profit organization located in St. Mary’s County. Walden’s website is http://www.waldensierra.org/. SOCIETY FOR THE PREVENTION OF TEEN SUICIDE This website, http://www.sptsusa.org/teens/, has a teen section where you can find information to help yourself or a friend who may be having suicidal thoughts. You can also find information on how to cope if a friend dies by suicide. THE TREVOR PROJECT HELPLINE 1-866-488-7386 The Trevor Helpline is a 24/7 free suicide hotline providing crisis intervention and suicide prevention services for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and questioning (LGBTQ) youth ages 13–24. -

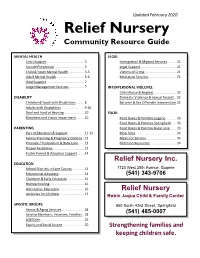

Community Resource Guide

Updated February 2020 Relief Nursery Community Resource Guide MENTAL HEALTH LEGAL Crisis Support ...................................... 3 Immigration & Migrant Services ......... 21 Suicide Prevention .............................. 3 Legal Support .................................... 21 Child & Youth Mental Health ............... 3-5 Victims of Crime ................................ 21 Adult Mental Health ............................ 5-6 Mediation Services ............................ 21 Grief Support ...................................... 7 Anger Management Services ............... 7 INTERPERSONAL VIOLENCE Child Abuse & Neglect ....................... 22 DISABILITY Domestic Violence & Sexual Assault .. 22 Children & Youth with Disabilities ........ 8 Batterer & Sex Offender Intervention 22 Adults with Disabilities ...................... 9-10 Deaf and Hard of Hearing .................... 10 FOOD Blindness and Vision Impairment ........ 10 Food Boxes & Pantries Eugene .......... 23 Food Boxes & Pantries Springfield ..... 23 PARENTING Food Boxes & Pantries Rural Lane ...... 23 Parent Education & Support ................ 11-12 Meal Sites ......................................... 24 Family Planning & Pregnancy Options . 12 Meals for Seniors............................... 24 Prenatal / Postpartum & Baby Care...... 13 Nutrition Resources .......................... 24 Diaper Assistance................................ 13 Foster Parent & Adoption Support....... 14 Relief Nursery Inc. EDUCATION School Districts in Lane County ............ 14 1720 -

Oregon Youth Suicide Prevention Guidelines

Photograph by Jason Dessel (1998) OORREEGGOONN YYOOUUTTHH SSUUIICCIIDDEE PPRREEVVEENNTTIIOONN YOUTH SUICIDE PREVENTION INTERVENTION & POSTVENTION GUIDELINES A Resource for School Personnel Developed by The Maine Youth Suicide Prevention Program A Program of Governor Angus S. King, Jr. And the Maine Children’s Cabinet May 2002 Modified for Oregon by Jill Hollingsworth, MA Looking Glass Youth and Family Services November 2007 (2nd revision) YOUTH SUICIDE PREVENTION, INTERVENTION & POSTVENTION GUIDELINES TABLE OF CONTENTS Page I. INTRODUCTION 1 II. RATIONALE FOR DEVELOPING AND IMPLEMENTING SUICIDE PREVENTION 4 AND INTERVENTION PROTOCOLS III. COMPONENTS OF SCHOOL-BASED SUICIDE PREVENTION 6 A. READINESS SURVEY FOR ADMINISTRATORS 9 IV. COMPONENTS OF SCHOOL- BASED SUICIDE INTERVENTION 13 A. ESTABLISHING SUICIDE PROTOCOLS WITHIN THE SCHOOL CRISIS 14 RESPONSE PLAN B. GUIDELINES FOR WHEN THE RISK OF SUICIDE HAS BEEN RAISED 14 C. GUIDELINES FOR MEDIUM TO HIGH RISK SITUATIONS 16 D. GUIDELINES FOR WHEN A SUICIDE INVOLVES A PACT 17 E. RESPONDING TO A STUDENT SUICIDE ATTEMPT ON SCHOOL PREMISES 18 F. GUIDELINES FOR A STUDENT SUICIDE ATTEMPT OFF SCHOOL PREMISES 19 G. GUIDELINES FOR WHEN A STUDENT RETURNS TO SCHOOL FOLLOWING 20 H. ABSENCE FOR SUICIDAL BEHAVIOR V. COMPONENTS OF SUICIDE POSTVENTION PLANNING 22 A. KEY CONSIDERATIONS 23 B. RESPONDING TO A SUICIDE 25 Appendix A – RESPONSE, a Comprehensive Suicide Awareness Program 32 Appendix B – Basic Suicide Prevention and Intervention Information 36 Appendix C – Short Version of Suicide Intervention and -

If You Or Someone You Know Is in Crisis, Contact the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), Call 911 Or Go to Your Nearest Emergency Room

If you or someone you know is in crisis, contact the National Suicide Prevention Hotline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255), call 911 or go to your nearest emergency room. The National Suicide Prevention Lifeline provides free and confidential emotional support to people in suicidal crisis or emotional distress 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. Local Resources Region 1 - Upper Peninsula Counties Covered: Alger County, Baraga County, Chippewa County, Delta County, Dickinson County, Gogebic County, Houghton County, Iron County, Keweenaw County, Luce County, Mackinac County, Marquette County, Menominee County, Ontonagon County, Schoolcraft County Alcona Health Center is a network of healthcare clinics offering behavioral health therapy services in all its geographic areas across northern Michigan 989-736-8157 https://www.alconahealthcenters.org/index.php/contact-us/ Copper Country Community Mental Health Services provides an array of mental health programs and services to persons in Baraga, Houghton, Keweenaw and Ontonagon counties 24 Hour emergency services: 1-800-526-5059 http://www.cccmh.org Gogebic County Community Mental Health Authority provides a complete range of services for all children and adults of Gogebic County who have a serious emotional disturbance, serious mental illness or developmental disability. They also operate a crisis response line for any individual in crisis 24 Hour emergency services: 1-800-348-0032 http://www.gccmh.org/ Hiawatha Behavioral Health provides comprehensive, integrated mental health, substance use disorder, and intellectual/developmental disability services that promote the health and quality of life of community members in Chippewa, Mackinac, and Schoolcraft counties 24 Hour emergency services: 1-800-839-9443 http://www.hbhcmh.org/ Luce-Mackinac-Alger-Schoolcraft (LMAS) District Health Department is dedicated to providing county residents with disease prevention, health promotion and emergency management through education and advocacy.