I I Hip-Hop and Racial Identification: an (Auto )Ethnographic Perspective

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Cowl Island/Page 19 Vol

BACK PAGE: Focus on student health Deanna Cioppa '07 Men's hoops win Think twice before going tanning for spring Are you getting enough sleep? Experts say reviews Trinity over West Virginia, break ... and get a free Dermascan in Ray extra naps could save your heart Hear Repertory Theater's bring Friars back Cafeteria this coming week/Page 4 from the PC health center/Page 8 latest, A Delicate into the running for Balance/Page 15 NCAA bid Est. 1935 Sarah Amini '07 Men's and reminisces about women’s track win riding the RIPTA big at Big East 'round Rhose Championships The Cowl Island/Page 19 Vol. LXXI No. 18 www.TheCowl.com • Providence College • Providence, R.I. February 22, 2007 Protesters refuse to be silenced by Jennifer Jarvis ’07 News Editor s the mild weather cooled off at sunset yesterday, more than 100 students with red shirts and bal loons gathered at the front gates Aof Providence College, armed with signs saying “We will not stop fighting for an end to sexual assault,” and “Vaginas are not vulgar, rape is vulgar.” For the second year in a row, PC students protested the decision of Rev. Brian J. Shanley, O.P., president of Providence College, to ban the production of The Vagina Monologues on 'campus. Many who saw a similar protest one year ago are asking, is this deja vu? Perhaps, but the cast and crew of The Vagina Monologues and many other sup porters said they will not stop protesting just because the production was banned last year. -

Played 2013 IMOJP

Reverse Running Atoms For Peace AMOK XL Recordings Hittite Man The Fall Re-Mit Cherry Red Pre-Mdma Years The Fall Re-Mit Cherry Red Voodoo Posse Chronic Illusion Actress Silver Cloud WERKDISCS Recommended By Dentists Alex Dowling On The Nature Of ElectricityHeresy Records And Acoustics Smile (Pictures Or It Didn't Happen) Amanda Palmer & TheTheatre Grand Is EvilTheft OrchestraBandcamp Stoerung kiteki Rmx Antye Greie-Ripatti minimal tunesia Antye Greie-Ripatti nbi(AGF) 05 Line Ain't Got No Love Beal, Willis Earl Nobody knows. XL Recordings Marauder Black Pus All My Relations Thrill Jockey 1,000 Years Black Pus All My Relations Thrill Jockey Records All Out of Sorts Black Pus All My Relations Thrill Jockey Abstract Body/Head Coming Apart Matador Records Sintiendo Bomba Estéreo Elegancia Tropical Soundway #Colombia Amidinine Bombino Nomad Cumbancha Persistence Of Death Borut Krzisnik Krzisnik: Lightning Claudio Contemporary La noche mas larga Buika La noche mas largaWarner Music Spain Super Flumina Babylonis Caleb Burhans Evensong Cantaloupe Music Waiting For The Streetcar CAN The Lost Tapes [DiscMute 1] Obedience Carmen Villain Sleeper Smalltown Supersound Masters of the Internet Ceramic Dog Your Turn Northern-Spy Records track 2 Chris Silver T & MauroHigh Sambo Forest, LonelyOzky Feeling E-Sound Spectral Churches Coen Oscar PolackSpectral Churches Narrominded sundarbans coen oscar polack &fathomless herman wilken Narrominded To See More Light Colin Stetson New History WarfareConstellation Vol. 3: To See More Light The Neighborhood Darcy -

Souls of Mischief: ’93 Still Infinity Tour Hits Pawtucket

Souls of Mischief: ’93 Still Infinity Tour Hits Pawtucket The Met played host to the Souls of Mischief during their 20-year anniversary tour of their legendary debut album, “’93 til Infinity”. This Oakland-based hip- hop group, comprised of four life-long friends, A-Plus, Tajai, Opio and Phesto, together has created one of the most influential anthems of the ‘90’s hip-hop movement: the title track of the album, ’93 ‘til Infinity. This song is a timeless classic. It has a simple, but beautifully melodic beat that works seamlessly with the song’s message of promoting peace, friendship and of course, chillin’. A perfect message to kick off a summer of music with. The crowd early on in the night was pretty thin and the supporting acts did their best to amp up the audience for the Souls of Mischief. When they took the stage at midnight, the shift in energy was astounding. They walked out on stage and the waning crowd filled the room in seconds. The group was completely unfazed by the relatively small showing and instead, connected with the crowd and how excited they were to be in Pawtucket, RI of all places. Tajai, specifically, reminisced about his youth and his precious G.I. Joes (made by Hasbro) coming from someplace called Pawtucket and how “souped” he was to finally come through. The show was a blissful ride through the group’s history, mixing classic tracks like “Cab Fare” with more recent releases, like “Tour Stories”. The four emcees seamlessly passed around the mic and to the crowd’s enjoyment, dropped a song from their well-known hip-hop super-group, Hieroglyphics, which includes the likes of Casual, Del Tha Funkee Homosapien and more. -

ARTIST TITLE FORMAT Marie-Mai Elle Et

ARTIST TITLE FORMAT Marie-Mai Elle et Moi 12" vinyl Brandi Carlile A Rooster Says 12" The Trews No Time For Later (Limited Edition) 2XLP Charli XCX Vroom Vroom EP 12" EP Ron Sexsmith Hermitage (RSD20EX) 12" vinyl Grouplove Broken Angel 12" My Chemical Romance Life On The Murder Scene (RSD20 EX) LP Black Keys Let's Rock (45 RPM Edition)(RSD20 EX) 2-LP k.d. lang & the Reclines Angel With A Lariat (RSD20 EX) LP k.d. lang Drag (RSD20 EX) 2-LP Phenomenon (Music From The Motion Picture) Music From The Motion Picture (RSD20 EX) 2-LP Music From the X-Files: The Truth and the Light Mark Snow (RSD20 EX) LP Batman & Robin (Music From and Inspired By Music From And Inspired By The Motion Picture) (RSD20 EX) 2-LP Avalon (Original Motion Picture Score) (RSD20 Randy Newman EX) LP Lethal Weapon (Original Motion Picture Soundtrack Soundtrack) (RSD20 EX) LP Metroland (Music and Songs From The Film Mark Knopfler (RSD20 EX) LP Austin Powers: The Spy Who Shagged Me Music From The Motion Picture Soundtrack (RSD20 EX) LP Music From The Motion Picture: Austin Powers In Soundtrack Goldmember (RSD20 EX) LP Randy Newman The Natural (RSD20 EX) LP Tonight In The Dark We're Seeing Colors (RSD20 Tegan and Sara EX) LP Gary Clark Jr. Pearl Cadillac (feat. Andra Day) (RSD20 EX) 10" EP Gorillaz G-Sides (RSD20 EX) LP Gorillaz D-Sides (RSD20 EX) 3-LP Neil Young Homegrown (RSD20 EX) LP Biffy Clyro Moderns (RSD20 EX) 7" Wale Wow…That's Crazy (RSD20 EX) LP Skid Row Slave To The Grind (Expanded) 2LP Live from the Apollo Theatre Glasgow Feb Alice Cooper 19.1982 2LP - 140gram black vinyl Fleetwood Mac The Alternate Rumours 1LP, 180gram, black vinyl 5-LP, 180-gram vinyl, with Grateful Dead Buffalo 5/9/77 10th-side etching. -

L the Charlatans UK the Charlatans UK Vs. the Chemical Brothers

These titles will be released on the dates stated below at physical record stores in the US. The RSD website does NOT sell them. Key: E = Exclusive Release L = Limited Run / Regional Focus Release F = RSD First Release THESE RELEASES WILL BE AVAILABLE AUGUST 29TH ARTIST TITLE LABEL FORMAT QTY Sounds Like A Melody (Grant & Kelly E Alphaville Rhino Atlantic 12" Vinyl 3500 Remix by Blank & Jones x Gold & Lloyd) F America Heritage II: Demos Omnivore RecordingsLP 1700 E And Also The Trees And Also The Trees Terror Vision Records2 x LP 2000 E Archers of Loaf "Raleigh Days"/"Street Fighting Man" Merge Records 7" Vinyl 1200 L August Burns Red Bones Fearless 7" Vinyl 1000 F Buju Banton Trust & Steppa Roc Nation 10" Vinyl 2500 E Bastille All This Bad Blood Capitol 2 x LP 1500 E Black Keys Let's Rock (45 RPM Edition) Nonesuch 2 x LP 5000 They's A Person Of The World (featuring L Black Lips Fire Records 7" Vinyl 750 Kesha) F Black Crowes Lions eOne Music 2 x LP 3000 F Tommy Bolin Tommy Bolin Lives! Friday Music EP 1000 F Bone Thugs-N-Harmony Creepin' On Ah Come Up Ruthless RecordsLP 3000 E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone LP E David Bowie ChangesNowBowie Parlophone CD E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone 2 x LP E David Bowie I’m Only Dancing (The Soul Tour 74) Parlophone CD E Marion Brown Porto Novo ORG Music LP 1500 F Nicole Bus Live in NYC Roc Nation LP 2500 E Canned Heat/John Lee Hooker Hooker 'N Heat Culture Factory2 x LP 2000 F Ron Carter Foursight: Stockholm IN+OUT Records2 x LP 650 F Ted Cassidy The Lurch Jackpot Records7" Vinyl 1000 The Charlatans UK vs. -

Youth-Renewing-The-Countryside.Pdf

renewing the youth countryside renewing the youth countryside youth : renewing the countryside A PROJECT OF: Renewing the Countryside PUBLISHED BY: Sustainable Agriculture Research & Education (SARE) WITH SUPPORT FROM THE CENTER FOR RURAL STRATEGIES AND THE W.K. KELLOGG FOUNDATION SARE’s mission is to advance—to the whole of American agriculture—innovations that improve profitability, stewardship and quality of life by investing in groundbreaking research and education. www.sare.org Renewing the Countryside builds awareness, support, and resources for farmers, artists, activists, entrepreneurs, educators, and others whose work is helping create healthy, diverse, and sustainable rural communities. www.renewingthecountryside.org A project of : Renewing the Countryside Published by : Sustainable Agriculture Research and Education (SARE) publishing partners Senior Editor : Jan Joannides Editors : Lisa Bauer,Valerie Berton, Johanna Divine SARE,Youth, and Sustainable Agriculture Renewing the Countryside Associate Editors : Jonathan Beutler, Dave Holman, Isaac Parks A farm is to a beginning farmer what a blank canvas Renewing the Countryside works to strengthen rural Creative Direction : Brett Olson is to an aspiring artist. It is no wonder then that areas by sharing information on sustainable America’s youth are some of agriculture’s greatest development, providing practical assistance and Design Intern : Eric Drommerhausen innovators and experimenters.The evidence is right here networking opportunities, and fostering connections between Lead Writers : Dave Holman and Nathalie Jordi between the covers of this book—youth driving rural renewal urban and rural citizens. by testing new ideas on farms, ranches, and research stations Lead Photographer : Dave Holman across the country. SARE supports these pioneers. In this book, This is the ninth in a series of books Renewing the Countryside read about the Bauman family farm in Kansas, the Full Belly Farm has created in partnership with others. -

Advocacy Day a Success What Is Advocacy? SHAY DENEY J

Building a world class foster care system while serving our neighborhood youth March 2004 Foster Care and Homeless Youth Speak out Across the Nation Volume IV, Issue 3 Visit us online at www.mockingbirdsociety.org Advocacy Day a Success What is Advocacy? SHAY DENEY J. EBOH Advocate n- One who argues for a cause; a supporter ON FEBRUARY 9TH I dragged myself out of bed at 7:30 or defender. in the morning. For me that is the equivalent of waking -American Heritage Dictionary up at the crack of dawn. In a half-dead state, I walked down to the nearest bus stop and got on a bus headed in The right to advocate is a privilege given to every- the direction of the University District Youth Center in one who lives in America. If that is so, then why do Seattle. I wasn’t the only kid doing this. Over 100 youth most people not even know what it means? across the Puget Sound area in Washington State, on Most people think of advocacy as a difficult and their own free time, were loading themselves into vans overwhelming thing to get involved with. True, with their peers from group homes, shelters and local there are people who do it for a living: meeting with youth centers. We were all heading down to Olympia legislators all the time and constantly fighting for (Washington state capitol) to participate in Youth important issues. What most people don’t know, Advocacy Day. Senator Rosa Franklin, Mockingbird Times reporter Princess Hollins, Tonya Greenfield, service providers and youth. -

MMS 001 MADLIB MEDICINE SHOW 1 Before the Verdict CD

MADLIB LAUNCHES HIS ONCE-A-MONTH ALBUM SERIES Madlib launches the Madlib Medicine MP3 leak “The Paper” downloaded Show, a once-a-month, twelve-CD, 43,000 times on stonesthrow.com six-LP series with Before The Verdict. The as of 12/10… and counting Madlib Medicine Show will be a Marketed and promoted by combination of Madlib's new Hip Hop Stones Throw Records productions, remixes, beat tapes, and Publicity by Score Press Jazz, as well as mixtapes of Funk, Soul, Brazilian, Psych and other undefined Limited edition forms of music from the Beat Konducta's 4-ton* stack of vinyl. Format: CD Cat. No: MMS 001 Madlib Medicine Show No. 1 is Before Label: Madlib Medicine Show The Verdict featuring Guilty Simpson, a Available: February 2nd, 2010 seventeen track reimagination of rapper Guilty Simpson’s Ode To The Ghetto (augmented, of course, with unreleased songs, other remixes and tons o’ beats). You can think of this as somewhat of a prelude to Madlib & Guilty Simpson's forthcoming OJ Simpson album. Volume 1 is a limited pressing of CDs. Next up: Flight to Brazil, is a mixtape of Brazilian jazz, funk, prog-rock, folk and psychedelia coming in late February. Later releases will include Beat Konducta in Africa. *4-tons of vinyl, this is true. It’s all in his studio. The World-Psych Masterpiece from The Whitefield Brothers 1. Joyful Exaltation feat. Bajka 2. Safari Strut 3. Reverse feat. Percee P and MED 4. Taisho 5. Sad Nile 6. The Gift feat. Edan and Mr. Lif 7. Ntu 8. -

Luigi's Tahoe Pizzeria

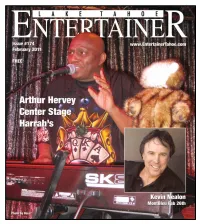

Publisher/Editor Boomerang Design Group Marketing/Sales Ross Orlando 775-588-5657 Joani Buzzetti-Drew 530-318-9994 Entertainment Columnist Photographer • Circulation Ross Orlando Feature Writers Ross Orlando Victor Babbitt • Howie Nave Dave Davis Late Nite Billy Art Director Production Tony Drew LAKE TAHOE ENTERTAINER 530.573.1376 P.O.Box 550996 South Lake Tahoe CA. 96155 E-Mail: [email protected] Fax: 530-573-1376 entertainertahoe.com What’s On & Where BEACH HUT DELI - 530-541-SURF LUIGI'S TAHOE PIZZERIA - 775-588-0442 Local's $5 Meal Deal - Happy Hour 4pm - Close Local Specials • Fast Lunch • $2 Tuesdays • Delivery BEACON BAR & GRILL - 530-541-0630 MacDUFFS PUB - 530-542-8777 Live Music - Lakeview Dining - Marina - Happy Hours Wood Fired Brick Pizza Oven Served 'till Midnight - Open 11am - 2am Daily Snowshoe Cocktail Races - Feb 12 & March 18 McP'S PUB TAHOE - 530-542-4435 BLUE ANGEL CAFÉ - 530-544-6544 Live Music - No Cover - Pool Table - Heated Patio - Drink Specials Breakfast - Lunch - Dnner - Daily Specials - Happy Hour MONTBLEU - 775-588-3515 BLUE WATER BISTRO- 530-541-0113 Bassnectar - Feb 11 & 12 • MMA - Feb 25 Spectacular Over-the-Lake Dining - Happy Hours Kevin Nealon and Friends - Feb 26 • Rob Sneider - March 26 OPAL ULTRA LOUNGE - Wednesday - dirty Beat Wednesday BROTHERS BAR & GRILL - 530-541-7017 Thursday - $1 Well drinks - dJ • Fridays - Ladies drink Free All Night Night - dJ Happy Hours 3pm - 8pm -Daily Specials - Fire Pit - Live Music - Rail Jams Saturday - Ladies Free Cover Before Midnight - dJ BUNNY RANCH - -

Oakland Museum of California Presents Ziggurat, a Powerful Fundraising Event with Personality and Purpose

CONTACT: Melissa Davis, 510-969-9212, [email protected] Lindsay WrigHt, 510-318-8467, [email protected] OAKLAND MUSEUM OF CALIFORNIA PRESENTS ZIGGURAT, A POWERFUL FUNDRAISING EVENT WITH PERSONALITY AND PURPOSE MAY 19 EVENT INSPIRED BY OMCA’S RESPECT: HIP-HOP STYLE & WISDOM EXHIBITION, INCLUDING A HEADLINING LIVE PERFORMANCE BY OAKLAND’S OWN HIEROGLYPHICS (Oakland, CA) May 3, 2018– Oakland Museum of California (OMCA) will present the third annual Ziggurat, a fundrAisinG event on SaturdAy, May 19 thAt is uniquely “Oakland”. At Ziggurat, Oakland’s vibrant local community comes togetHer to celebrate tHe Museum with a party tHat is far from tHe typical fundraising event. OMCA’s popular exhibition RESPECT: Hip-Hop Style & Wisdom insPires the eveninG, from atmosphere to entertainment, with OaklAnd’s own leGendAry Hip-Hop collective HieroGlyPhics heAdlininG ZiGGurAt Late NiGht. Ziggurat guests will begin tHeir evening at 6 pm witH cocktails on tHe garden terrace and exclusive access to RESPECT: Hip-Hop Style & Wisdom, followed by dinner catered by Barbara Llewelyn Catering and a live auction and fund- a-need. A Hip-Hop dance performance by Destiny Arts Center’s Junior Company will follow tHe auction. Craft cocktails will be provided by St. George Spirits, wine by Purple Wine and Spirits, and music by DJ HeyLove*. Immediately following the dance performance, guests can stay and enjoy Ziggurat Late Night, witH moutH-watering bites, open bars, and live entertAinment by Souls of Mischief, CAsuAl, Domino, DJ Toure, PeP Love And Del the Funky HomosAPien of HieroGlyPhics. Guests may choose to attend tHe Late NigHt event only, from 9 pm to 12 am, by purchasing a Ziggurat Late NigHt ticket. -

BW-July-WEB.Pdf

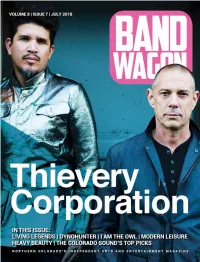

FRIDAY JULY 6TH SATURDAY JULY 7TH THURSDAY JULY 12TH FRIDAY JULY 13TH SATURDAY JULY 14TH FRIDAY JULY 20TH SATURDAY JULY 21ST SUNDAY JULY 22ND FRIDAY JULY 27TH SATURDAY JULY 28TH THURS. AUGUST 2ND FRIDAY AUGUST 3RD THURS. AUGUST 9TH FRIDAY AUGUST 10TH SATURDAY AUGUST 11TH ...AND MUCH MORE: 8.16 - FLATLAND CAVALRY | 8.17 - MAGIC MIKE XXL | 8.18 - ORGY “bRING YOUR ARMY TOUR” w/ MOTOGRATER | 8.19 - LIL DEBBIE W/ WHITNEY PEYTON 8.21 - THE NIGHT OWLS | 8.22 - THE MYSTERY COLLECTION PRESENTS - PAUL NOFFSINGER: UNREAL | 9.14 - MY FAVORITE BANDS | 9.21 - BLOCK PARTY BandWagMag BandWagMag BandWagMag 802 9th St. album reviews Greeley, CO 80631 I AM THE OWL PG. 5 BANDWAGMAG.COM MODERN LEISURE PG. 6 www.BandWagMag.com HEAVY BEAUTY PG. 7 PUBLISHER ELY CORLISS EDITOR-IN-CHIEF JED MURPHY MANAGING EDITOR KEVIN JOHNSTON ART DIRECTOR JACK “JACK” JORDAN PHOTOGRAPHY DYNOHUNTER LIVING LEGENDS PG. 10-11 PG. 14-15 TALIA LEZAMA CONTRIBUTORS KYLE EUSTICE CAITLYN WILLIAMS JAY WALLACE MICHAEL OLIVIER THE COLORADO SoUND’S TOP PICKS PG 8 Advertising Information: [email protected] Any other inquires: [email protected] BandWagon Magazine PG. 18-19 © 2018 The Crew Presents Inc. THIEVERY CORPORATION 3 | BANDWAGON MAGAZINE BANDWAGON MAGAZINE | 4 I Am The Owl A PLACE WHERE A Mission to Civilize: Part II YOU CAN TRUST YOURSELF Michael Olivier and Kyle Krueckeberg’s vocals BandWagon Magazine to tear through in a new way that’s sure to get you pumped. I find myself coming back to the fourth track on the album, BE “You Haven’t Fooled Me.” The REMARKABLE middle of the tune features a massive, almost progressive rock instrumental section that plays heavily with dynamics, shifting drum grooves, and mul- tiple tasty guitar licks for those local ear-candy seekers. -

![Phonte Pacific Time Torrent Download Phonte – Pacific Time [EP Stream] Whenever Phonte Releases New Music, It’S Always an Occasion](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5173/phonte-pacific-time-torrent-download-phonte-pacific-time-ep-stream-whenever-phonte-releases-new-music-it-s-always-an-occasion-2815173.webp)

Phonte Pacific Time Torrent Download Phonte – Pacific Time [EP Stream] Whenever Phonte Releases New Music, It’S Always an Occasion

phonte pacific time torrent download Phonte – Pacific Time [EP Stream] Whenever Phonte releases new music, it’s always an occasion. After putting rap at the forefront for last year’s No News Is Good News album, he’s making singing the focus for his next surprise release — an EP called Pacific Time . The project features four tracks from the multi-talented North Carolina artist, with contributions coming from Kaytranada, BOSCO and Devin Morrison. For those wanting to hear some bars, no fear — he spits a verse on the closing track, “Heard This One Before.” And it’s a summer heater at that. Phonte Has Just Released A Surprise EP. Listen Here. With less than 24 hours notice, Phonte just released his second project since last March. 2018’s No News Is Good News marked the North Carolina MC/singer/producer’s first solo effort and Rap album in nearly seven years. It was subsequently named one of 2018’s best efforts by Ambrosia For Heads . For 2019, the Little Brother and Foreign Exchange co-founder (plus Questlove Supreme co-host) follows up with Pacific Time. At around noon EST on Thursday (March 28), Phonte announced that he would be dropping the new body of work at the start of Friday, attaching the project’s artwork. Freshly arrived, the four-song release features KAYTRANADA, Devin Morrison, and Bosco. Kaytranada, who involved ‘Te on 2016’s 99.9% , also produces “Heard This One Before.” Grammy-nominated producer (and Pac Div member) Like co-produces “Beverly Hills,” alongside Devin Morrison and Swarvy. Phonte handles the work behind the boards on “Ego.” Longtime Phonte collaborator plays keys, keys, and bass on multiple songs.