The Conservation Status and Population Decline of the African

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

KELP BLUE NAMIBIA (Pty) Ltd

KELP BLUE NAMIBIA (Pty) Ltd EIA SCOPING & IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT AND ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PLAN FOR THE PROPOSED KELP CULTIVATION PILOT PROJECT NEAR LÜDERITZ, KARAS REGION Prepared for: Kelp Blue Namibia (Pty) Ltd August 2020 1 DOCUMENT CONTROL Report Title EIA SCOPING & IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR THE PROPOSED KELP CULTIVATION PILOT PROJECT NEAR LÜDERITZ, KARAS REGION Report Author Werner Petrick Client Kelp Blue Namibia (Pty) Ltd Project Number NSP2020KB01 Report Number 1 Status Final to MEFT and MFMR Issue Date August 2020 DISCLAIMER The views expressed in the document are the objective, independent views of the author with input from various Environmental and Social Experts (i.e. Specialists). Neither Werner Petrick nor Namisun Environmental Projects and Development (Namisun) have any business, personal, financial, or other interest in the proposed Project apart from fair remuneration for the work performed. The content of this report is based on the author’s best scientific and professional knowledge, input from the Environmental Specialists, as well as available information. Project information contained herein is based on the interpretation of data collected and data provided by the client, accepted in good faith as being accurate and valid. Namisun reserves the right to modify the report in any way deemed necessary should new, relevant, or previously unavailable or undisclosed information become available that could alter the assessment findings. This report must not be altered or added to without the prior written consent of the author. Project Nr: NSP2020KB01 EIA SCOPING & IMPACT ASSESSMENT REPORT AND EMP FOR August 2020 Report number: 1 THE PROPOSED KELP CULTIVATION PILOT PROJECT 2 Table of Contents 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. -

Federal Register/Vol. 75, No. 187/Tuesday, September 28, 2010

Federal Register / Vol. 75, No. 187 / Tuesday, September 28, 2010 / Rules and Regulations 59645 * Elevation in feet (NGVD) + Elevation in feet (NAVD) Flooding source(s) Location of referenced elevation # Depth in feet Communities above ground affected ∧ Elevation in meters (MSL) Modified Unnamed Tributary No. 1 to At the area bounded by U.S. Route 33, Wabash Avenue, +1415 Unincorporated Areas of Fink Run (Backwater effects and County Route 33/1. Upshur County. from Buckhannon River). * National Geodetic Vertical Datum. + North American Vertical Datum. # Depth in feet above ground. ∧ Mean Sea Level, rounded to the nearest 0.1 meter. ADDRESSES Unincorporated Areas of Upshur County Maps are available for inspection at the Upshur County Courthouse Annex, 38 West Main Street, Buckhannon, WV 26201. (Catalog of Federal Domestic Assistance No. 76.913(b)(1)—62 FR 6495, February 12, collection requirements that are subject 97.022, ‘‘Flood Insurance.’’) 1997. to OMB approval. Dated: September 21, 2010. 76.924(e)(1)(iii) and (e)(2)(iii)—61 FR [FR Doc. 2010–24203 Filed 9–27–10; 8:45 am] Edward L. Connor, 9367, March 8, 1996. BILLING CODE 6712–01–P Acting Federal Insurance and Mitigation 76.925—60 FR 52119, October 5, 1995. Administrator, Department of Homeland 76.942(f)—60 FR 52120, October 5, Security, Federal Emergency Management 1995. DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Agency. 76.944(c)—60 FR 52121, October 5, [FR Doc. 2010–24326 Filed 9–27–10; 8:45 am] 1995. Fish and Wildlife Service BILLING CODE 9110–12–P 76.957—60 FR 52121, October 5, 1995. -

Penguin Camp)

Appendix 1.2 PENGUIN Conservation Assessment and Management Plan (PENGUIN CAMP) Report from a Workshop held 8-9 September 1996, Cape Town, South Africa Edited by Susie Ellis, John P. Croxall and John Cooper Data sheet for the African Penguin Spheniscus demersus African Penguin Spheniscus demersus STATUS: New UCN Category: Vulnerable Based on: A1a, A2b, E CITES: Appendix II OTHER: In South Africa, endangered in terms of the Nature and Environmental Conservation Ordinance, No. 19 of 1974 of the Province of the Cape of Good Hope. This now applies to the Northern Cape, Western Cape and Eastern Cape Provinces. In Namibia, there is no official legal status. Listed as Near Threatened in Birds to Watch 2 (Collar et al. 1994). Listed as Vulnerable in the Red Data Book for South Africa, Lesotho and Swaziland (Crawford 2000). Listed in Appendix II of the Convention for the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals (Bonn Convention). Taxonomic status: Species. Current distribution (breeding and wintering): Breeding distribution: Between Hollams Bird Island, Namibia and Bird Island, Algoa Bay, South Africa. Number of locations: 27 extant breeding colonies - eight islands and one mainland site along the coast of southern Namibia; 10 islands and two mainland sites along the coast of Western Cape Province, South Africa; six islands in Algoa Bay, Eastern Cape Province, South Africa (Crawford et al. 1995a). There is no breeding along the coast of South Africa's Northern Cape Province, which lies between Namibia and Western Cape Province. Concentrated Migration Regions: None. Juveniles tend to disperse along the coastline to the west and north (Randall et al. -

Walvis Bay: South Africa's Claims to Sovereignty

Denver Journal of International Law & Policy Volume 16 Number 2 Winter/Spring Article 4 May 2020 Walvis Bay: South Africa's Claims to Sovereignty Earle A. Partington Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/djilp Recommended Citation Earle A. Partington, Walvis Bay: South Africa's Claims to Sovereignty, 16 Denv. J. Int'l L. & Pol'y 247 (1988). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Denver Sturm College of Law at Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Journal of International Law & Policy by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],dig- [email protected]. Walvis Bay: South Africa's Claims to Sovereignty EARLE A. PARTINGTON* I. INTRODUCTION After more than a century of colonial domination, the Mandated Territory of South West Africa/Namibia' is close to receiving-its indepen- dence. South Africa continues to administer the Territory as it has since its military forces conquered and occupied it in 1915 during World War I. In the negotiations between South Africa and the United Nations over Namibian independence, differences have arisen between the parties over whether the Territory includes either (1) the port and settlement of Walvis Bay, an enclave of 1124 square kilometers in the center of Namibia's Atlantic coast, or (2) the Penguin Islands, twelve small guano islands strung along 400 kilometers of the Namibian coast between Walvis Bay and the Orange River, the Orange River being part of the boundary between South Africa and Namibia. -

Partitioning of Nesting Space Among Seabirds of the Benguela Upwelling Region

PARTITIONING OF NESTING SPACE AMONG SEABIRDS OF THE BENGUELA UPWELLING REGION DAviD C. DuFFY & GRAEME D. LA CocK Percy FitzPatrick Institute of African Ornithology, University of Cape Town, Rondebosch, South Africa, 7700. Received February /985 SUMMARY DuFFY, D. C. & LA CocK, G. D. 1985. Partitioning of nesting space among seabirds of the Benguela upwel ling region. Ostrich 56: 186-201. An examination of nesting habitats used by the four main species of seabirds nesting on southern African islands (Jackass Penguin Spheniscus demersus, Cape Cormorant Phalacrocorax capensis, Bank Cormorant P. neglectus and Cape Gannet Morus capensis) revealed relatively minor differences and extensive over laps between species, primarily in subcolony size, steepness of nesting substratum, and proximity to cliffs. A weak dominance hierarchy existed; gannets could displace penguins, and penguins could displace cor morants. This hierarchy appeared to have little effect on partitioning of nesting space. Species successfully defended occupied sites in most cases of interspecific conflict, suggesting that site tenure by one species could prevent nesting by another. The creation of additional nesting space on Namibian nesting platforms did not increase guano harvests, suggesting that nesting space had not previously limited the total nesting population of Cape Cormorants, the most abundant of the breeding species, in Namibia. While local shortages of nesting space may occur, populations of the four principal species of nesting seabirds in the Benguela upwelling region do not seem to have been limited by the availability of nesting space on islands. INTRODUCTION pean settlement, space for nesting was limited. Af ter settlement, human disturbance such as hunting The breeding seabirds of the Benguela upwel and guano extraction reduced nesting space, re ling region off Namibia and South Africa are be sulting in smaller populations of nesting seabirds. -

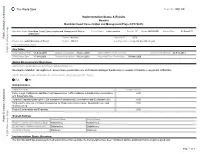

Implementation Status & Results

The World Bank Report No: ISR11851 Implementation Status & Results Namibia Namibian Coast Conservation and Management Project (P070885) Operation Name: Namibian Coast Conservation and Management Project Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 17 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 24-Sep-2013 (P070885) Public Disclosure Authorized Country: Namibia Approval FY: 2006 Product Line:Global Environment Project Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Sep-2005 Original Closing Date 31-Dec-2015 Planned Mid Term Review Date Last Archived ISR Date 27-Feb-2013 Effectiveness Date 17-Oct-2005 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2015 Actual Mid Term Review Date 09-Mar-2009 Global Environmental Objectives Global Environmental Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) Development/Global: Strengthened conservation, sustainable use and mainstreaming of biodiversity in coastal and marine ecosystems in Namibia Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Policy, Legal, Institutional and Planning Framework for ICZM conducive to Biodiversity Conservation 0.00 and Sustainable Use Targeted Capacity-Building for ICZM conducive to Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Use 0.00 Targeted Investments in Critical Ecosystems for Biodiversity Conservation, Sustainable Use and 0.00 Mainstreaming Project Coordination and Reporting 0.00 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Public Disclosure Authorized Progress towards achievement of GEO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Moderate Moderate Public Disclosure Copy Implementation Status Overview The first NACOMA has always performed well and the activities under the first operation have been concluded and the additional finance is up to a good start. -

7 Receiving Environment

Total E and P Namibia B.V. 733.20071.00002 Proposed 3D Seismic Survey in Licence Blocks 2912 and 2913B, Orange Basin, Namibia: Draft EIA Report & ESMP October 2020 7 RECEIVING ENVIRONMENT This chapter provides a description of the attributes of the physical, biological, socio-economic and cultural receiving environment of the licence area and the central to southern Namibian offshore regional area. An understanding of the environmental and social context and sensitivity within which the proposed project activities would be located is important to understanding the potential impacts. 7.17.17.1 AREA OF INFLUENCE The Area of Influence of the project considers the spatial extent of potential direct and indirect impacts of the project and this is used to define the boundaries for baseline data gathering. The International Finance Corporation (IFC) Performance Standard (PS) 1 defines a " Project's Area of Influence encompasses, as appropriate: • The area likely to be affected by: o the project and the client's activities and facilities that are directly owned, operated or managed (including by contractors) and that are a component of the project; o impacts from unplanned but predictable developments caused by the project that may occur later or at a different location; or o indirect project impacts on biodiversity or on ecosystem services upon which affected communities’ livelihoods are dependent. • Associated facilities, which are facilities that are not funded as part of the project and that would not have been constructed or expanded if the project did not exist and without which the project would not be viable. • Cumulative impacts that result from the incremental impact, on areas or resources used or directly impacted by the project, from other existing, planned or reasonably defined developments at the time the risks and impacts identification process is conducted ". -

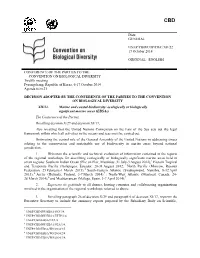

XII/22 17 October 2014

CBD Distr. GENERAL UNEP/CBD/COP/DEC/XII/22 17 October 2014 ORIGINAL: ENGLISH CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY Twelfth meeting Pyeongchang, Republic of Korea, 6-17 October 2014 Agenda item 21 DECISION ADOPTED BY THE CONFERENCE OF THE PARTIES TO THE CONVENTION ON BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY XII/22. Marine and coastal biodiversity: ecologically or biologically significant marine areas (EBSAs) The Conference of the Parties, Recalling decision X/29 and decision XI/17, Also recalling that the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea sets out the legal framework within which all activities in the oceans and seas must be carried out, Reiterating the central role of the General Assembly of the United Nations in addressing issues relating to the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity in marine areas beyond national jurisdiction, 1. Welcomes the scientific and technical evaluation of information contained in the reports of the regional workshops for describing ecologically or biologically significant marine areas held in seven regions: Southern Indian Ocean (Flic en Flac, Mauritius, 31 July-3 August 2012);1 Eastern Tropical and Temperate Pacific (Galapagos, Ecuador, 28-31 August 2012; 2 North Pacific (Moscow, Russian Federation, 25 February-1 March 2013); 3 South-Eastern Atlantic (Swakopmund, Namibia, 8-12 April 2013); 4 Arctic (Helsinki, Finland, 3-7 March 2014) 5 ; North-West Atlantic (Montreal, Canada, 24- 28 March 2014);6 and Mediterranean (Málaga, Spain, 3-7 April 2014);7 2. Expresses its gratitude to all donors, hosting countries and collaborating organizations involved in the organization of the regional workshops referred to above; 3. -

World Bank Document

The World Bank Report No: ISR7062 Implementation Status & Results Namibia Namibian Coast Conservation and Management Project (P070885) Operation Name: Namibian Coast Conservation and Management Project Project Stage: Implementation Seq.No: 15 Status: ARCHIVED Archive Date: 10-Oct-2011 (P070885) Public Disclosure Authorized Country: Namibia Approval FY: 2006 Product Line:Global Environment Project Region: AFRICA Lending Instrument: Specific Investment Loan Implementing Agency(ies): Ministry of Environment and Tourism (MET), Ministry of Regional and Local Government and Housing and Rural Development (MRLGHRD) Key Dates Public Disclosure Copy Board Approval Date 01-Sep-2005 Original Closing Date 30-Apr-2011 Planned Mid Term Review Date Last Archived ISR Date 10-Oct-2011 Effectiveness Date 17-Oct-2005 Revised Closing Date 31-Dec-2012 Actual Mid Term Review Date 09-Mar-2009 Global Environmental Objectives Global Environmental Objective (from Project Appraisal Document) Development/Global: Strengthened conservation, sustainable use and mainstreaming of biodiversity in coastal and marine ecosystems in Namibia Has the Project Development Objective been changed since Board Approval of the Project? Yes No Public Disclosure Authorized Component(s) Component Name Component Cost Policy, Legal, Institutional and Planning Framework for ICZM conducive to Biodiversity Conservation 0.00 and Sustainable Use Targeted Capacity-Building for ICZM conducive to Biodiversity Conservation and Sustainable Use 0.00 Targeted Investments in Critical Ecosystems for Biodiversity Conservation, Sustainable Use and 0.00 Mainstreaming Project Coordination and Reporting 0.00 Overall Ratings Previous Rating Current Rating Public Disclosure Authorized Progress towards achievement of GEO Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Implementation Progress (IP) Satisfactory Satisfactory Overall Risk Rating Moderate Moderate Public Disclosure Copy Implementation Status Overview A World Bank implementation support mission took place from March 28 to April 5, 2012. -

Draft MSAP Benguela Seabirds

Annexes 1 and 2 to document MOP6.30 Draft International Multi-species Action Plan for the Conservation of the Benguela Current Upwelling System Coastal Seabirds Annexes Annex 1: Threats 1. Lack of food and low quality prey Lack of preferred prey species, and consequent reliance by some species/populations on lower- quality prey, is one of the main factors behind low breeding success of the African Penguin, Cape Gannet and Cape and Bank Cormorants (Lewis et al. 2006; Roy et al., 2007; Coetzee et al., 2008; Gremillet et al., 2008; Crawford et al., 2006, 2011). Excluding the Bank Cormorant whose main prey species is pelagic goby in Namibia and West Coast rock lobster in South Africa (Crawford et al., 1985, 2008), the remaining bird species forage mainly for sardine and anchovy. In the Benguela system, relatively discrete stocks of both sardine and anchovy are found to the north and south of an area of intense upwelling near Lüderitz, Namibia (Crawford, 1998). During the breeding season, which places high energy demands on adults, breeders are restricted to a smaller foraging range and require access to their preferred prey, and lack thereof is a main reason behind poor breeding success recorded in recent decades (Pichegru et al., 2007; Crawford et al., 2008). The lack of prey species is related to two main factors: overfishing and large-scale periodic environmental changes in the ecosystem, such as El Nino. In the 1950s and 1960s sardine stocks were abundant, and between Namibia and South Africa some 13.5 million tons were harvested by the purse-seine fishery. -

Namibian Islands' Marine Protected Area

Namibian Islands’ Marine Protected Area WWF South Africa Report Series – 2008/Marine/003 Project funded by WWF South Africa and NACOMA, in partnership with Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR) Compiled by: Heidi Currie1, Kolette Grobler2 and Jessica Kemper2 with contributions from Jean-Paul Roux, Bronwen Currie, Nadine Moroff, Katta Ludynia, Rian Jones, Joan James, Pavs Pillay, Nathalie Cadot, Kathie Peard, Vera de Couwer and Hannes Holtzhausen 1Namibian Marine Ecosystem Project 1 Strand Street, P O Box 912, Swakopmund, Namibia Email: [email protected] 2Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR) Luderitz P O Box 394, Shark Island, Namibia Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] JULY 2008 NAMIBIAN ISLANDS’ MARINE PROTECTED AREA Executive Summary In response to the worldwide depletion of many fish stocks and other marine resources, commonly associated with over-fishing, unsustainable harvesting practices and uncontrolled human impacts, a clear global thrust has emerged towards a holistic management approach that takes account of entire ecosystems, multiple sectors and various management objectives. The necessity of marine habitat protection to promote sustainable marine resource use and marine biodiversity conservation1 has recently been realized2 and a number of coastal states have embarked on the creation of networks of Marine Protected Areas (MPAs). One of the primary purposes of MPAs is to facilitate fisheries management, particularly the management of components of marine ecosystems that are not protected by traditional fisheries management. MPAs are regarded as one of the essential tools in the implementation of the ecosystem approach to fisheries (EAF)3 management, a legal commitment in the SADC Fisheries Protocol, and a management approach embraced by the Namibian Ministry of Fisheries and Marine Resources (MFMR). -

BANK CORMORANT | Phalacrocorax Neglectus

BANK CORMORANT | Phalacrocorax neglectus J-P Roux; J Kemper | Reviewed by: T Cook; K Ludynia; AJ Williams DISTRIBUTION AND ABUNDANCE Of the three marine cormorants endemic to the southern African oceans, this species is the most threatened. Globally, Bank Cormorants breed in small colonies between Hollamsbird Island, Namibia, and Quoin Rock, South Africa (du Toit et al. 2003, Kemper et al. 2007b). In Namibia, Bank © Jessica Kemper Cormorants breed on 14 islands and rocks, in one coastal cave and on one mainland jetty (Cooper 1981, Crawford et Conservation Status: Endangered al. 1999, Bartlett et al. 2003, Roux et al. 2003, Kemper et al. 2007b). Small numbers of Bank Cormorants in breeding Southern African Range: Coastal Namibia, South Africa plumage carrying nesting material have been observed at the Mile 4 Salt Works north of Swakopmund; however, Area of Occupancy: 23,300 km2 breeding there has not been confirmed (M Boorman pers. comm.). The non-breeding distribution in Namibia extends Population Estimate: 2,600 to 3,100 breeding north to Hoanibmond (Cooper 1984, Williams 1987a, pairs in Namibia Crawford 1997a). The Bank Cormorant occupies an area of 23,300 km2 in Namibia. Population Trend: >50% decline in the last three generations In 2010, the Namibian breeding population numbered Habitat: Coastal islands and rocks, between 2,600 and 3,100 breeding pairs (Table 2.6), protected mainland sites, comprising about 86% of the global population; Mercury inshore marine waters Island supported 81% of the Namibian and 72% of the global breeding population. Between 1993 and 1998 Threats: Lack of quality prey base, the Namibian breeding population is estimated to extreme weather events, have declined by 68%, a loss mainly attributable to the disturbance, predation by population crash after 1994/95 at Ichaboe Island, once the gulls and seals, pollution most important breeding locality for the species.