The Problems and Promises of the Holy Fool in Francesco, Giullare Di

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Teacher's Guide for Grade Five, Preliminary National Science

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 14.8 619 SE 023 745 TITLE COPES, Conceptually Oriented' Prqgram in Elementary Science: Teacher's Guide for Grade Five, Preliminary Edition. INSTITUTION New York Univ., N.Y. Center for Field Researcli:and School Services. SPONS AGENCY National Science Foundation, Washington, D.C.; Office . - of Education (DHEW), Washington, D.C. PUB DATE . 73 NOTE . 437p.: For related documents, see SE 023 743-744 and ED 054 939; Not available in hard copy due to copyright restrictions AVAILABLE FROM Center for Educational Research, -New York University, 11 Press Building, Washington Square, New York, N.Y. 10003 ($8.40; over 10, .less, 2%, over 25, 'less 5%) EDRS PRICE, HF-$0.83,Plus Postage. HC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Curriculum; *Curriculum Development; Curriculum Guides; Elementary Education; *Elementary School Science; *Grade 5;- Science CurriculuM; Science Education; *teaching Guides IDENTIFIERS *Conceptually Oriented Program Elementary Science . ABSTRACT This ddcument provides the teacher's guide for grade five for the Conceptually Oriented Program in ElementaryScience (COPES) science curriculum project. The guide includes an introduction to COPES, instructions for using .the guides instructions . for assessment of student's grade 4 mastery of science concepts,-and five science units. Each unit includes from three to live activities and an assessment. Unit topics include: cells, work, heat, energy transformations, and investigating populations. Each activity includes a teaching sequence and commentary. 014 *********************************************************,*********** * Documents acquired by ERIC 'include many informal unpublished '* * materials not available from other sources. ERIC makeS every effort * * to obtain the best copy available. re-yerthelesS, items of marginal * ..,*reproducibility are 'often encountered and this affects the quality * /Of the microfidhe and hardcopy, reproductions ERIC makes available * * via the ERIC Document Reproduction Service (EDRS). -

The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones 5-2010 The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira Shannon Victoria Stevens University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Repository Citation Stevens, Shannon Victoria, "The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira" (2010). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 371. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/1606942 This Thesis is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Thesis in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Thesis has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE RHETORICAL SIGNIFICANCE OF GOJIRA by Shannon Victoria Stevens Bachelor of Arts Moravian College and Theological Seminary 1993 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts in Communication Studies Department of Communication Studies Greenspun College of Urban Affairs Graduate College University of Nevada, Las Vegas May 2010 Copyright by Shannon Victoria Stevens 2010 All Rights Reserved THE GRADUATE COLLEGE We recommend the thesis prepared under our supervision by Shannon Victoria Stevens entitled The Rhetorical Significance of Gojira be accepted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Communication Studies David Henry, Committee Chair Tara Emmers-Sommer, Committee Co-chair Donovan Conley, Committee Member David Schmoeller, Graduate Faculty Representative Ronald Smith, Ph. -

Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10Pm in the Carole L

Mike Traina, professor Petaluma office #674, (707) 778-3687 Hours: Tues 3-5pm, Wed 2-5pm [email protected] Additional days by appointment Media 10: Film Appreciation Wednesdays 6-10pm in the Carole L. Ellis Auditorium Course Syllabus, Spring 2017 READ THIS DOCUMENT CAREFULLY! Welcome to the Spring Cinema Series… a unique opportunity to learn about cinema in an interdisciplinary, cinematheque-style environment open to the general public! Throughout the term we will invite a variety of special guests to enrich your understanding of the films in the series. The films will be preceded by formal introductions and followed by public discussions. You are welcome and encouraged to bring guests throughout the term! This is not a traditional class, therefore it is important for you to review the course assignments and due dates carefully to ensure that you fulfill all the requirements to earn the grade you desire. We want the Cinema Series to be both entertaining and enlightening for students and community alike. Welcome to our college film club! COURSE DESCRIPTION This course will introduce students to one of the most powerful cultural and social communications media of our time: cinema. The successful student will become more aware of the complexity of film art, more sensitive to its nuances, textures, and rhythms, and more perceptive in “reading” its multilayered blend of image, sound, and motion. The films, texts, and classroom materials will cover a broad range of domestic, independent, and international cinema, making students aware of the culture, politics, and social history of the periods in which the films were produced. -

From 'Scottish' Play to Japanese Film: Kurosawa's Throne of Blood

arts Article From ‘Scottish’ Play to Japanese Film: Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood Dolores P. Martinez Emeritus Reader, SOAS, University of London, London WC1H 0XG, UK; [email protected] Received: 16 May 2018; Accepted: 6 September 2018; Published: 10 September 2018 Abstract: Shakespeare’s plays have become the subject of filmic remakes, as well as the source for others’ plot lines. This transfer of Shakespeare’s plays to film presents a challenge to filmmakers’ auterial ingenuity: Is a film director more challenged when producing a Shakespearean play than the stage director? Does having auterial ingenuity imply that the film-maker is somehow freer than the director of a play to change a Shakespearean text? Does this allow for the language of the plays to be changed—not just translated from English to Japanese, for example, but to be updated, edited, abridged, ignored for a large part? For some scholars, this last is more expropriation than pure Shakespeare on screen and under this category we might find Kurosawa’s Throne of Blood (Kumonosu-jo¯ 1957), the subject of this essay. Here, I explore how this difficult tale was translated into a Japanese context, a society mistakenly assumed to be free of Christian notions of guilt, through the transcultural move of referring to Noh theatre, aligning the story with these Buddhist morality plays. In this manner Kurosawa found a point of commonality between Japan and the West when it came to stories of violence, guilt, and the problem of redemption. Keywords: Shakespeare; Kurosawa; Macbeth; films; translation; transcultural; Noh; tragedy; fate; guilt 1. -

DVD Press Release

DVD press release Kurosawa Classic Collection 5-disc box set Akira Kurosawa has been hailed as one of the greatest filmmakers ever by critics all over the world. This, the first of two new Kurosawa box sets from the BFI this month, brings together five of his most profound masterpieces, each exploring the complexities of life, and includes two previously unreleased films. An ideal introduction to the work of the master filmmaker, the Kurosawa Classic Collection contains Ikiru (aka Living), I Live in Fear and Red Beard along with the two titles new to DVD, the acclaimed Maxim Gorky adaptation The Lower Depths and Kurosawa’s first colour film Dodes’ka-den (aka Clickety-clack). The discs are accompanied by an illustrated booklet of film notes and credits and selected filmed introductions by director Alex Cox. Ikiru (Living), 1952, 137 mins Featuring a beautifully nuanced performance by Takashi Shimura as a bureaucrat diagnosed with stomach cancer, Ikiru is an intensely lyrical and moving film which explores the nature of existence and how we find meaning in our lives. I Live in Fear (Ikimono no Kiroku), 1955, 99 mins Made at the height of the Cold War, with the destruction of Hiroshima and Nagasaki still a recent memory, Toshiro Mifune delivers an outstanding performance as a wealthy foundry owner who decides to move his entire family to Brazil to escape the nuclear holocaust which he fears is imminent. The Lower Depths (Donzonko), 1957, 120 mins Once again working with Toshiro Mifune, Kurosawa adapts Maxim Gorky’s classic play of downtrodden humanity. -

The Historian-Filmmaker's Dilemma: Historical Documentaries in Sweden in the Era of Häger and Villius

ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS Studia Historica Upsaliensia 210 Utgivna av Historiska institutionen vid Uppsala universitet genom Torkel Jansson, Jan Lindegren och Maria Ågren 1 2 David Ludvigsson The Historian-Filmmaker’s Dilemma Historical Documentaries in Sweden in the Era of Häger and Villius 3 Dissertation in History for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy presented at Uppsala University in 2003 ABSTRACT Ludvigsson, David, 2003: The Historian-Filmmaker’s Dilemma. Historical Documentaries in Sweden in the Era of Häger and Villius. Written in English. Acta Universitatis Upsalien- sis. Studia Historica Upsaliensia 210. (411 pages). Uppsala 2003. ISSN 0081-6531. ISBN 91-554-5782-7. This dissertation investigates how history is used in historical documentary films, and ar- gues that the maker of such films constantly negotiates between cognitive, moral, and aes- thetic demands. In support of this contention a number of historical documentaries by Swedish historian-filmmakers Olle Häger and Hans Villius are discussed. Other historical documentaries supply additional examples. The analyses take into account both the produc- tion process and the representations themselves. The history culture and the social field of history production together form the conceptual framework for the study, and one of the aims is to analyse the role of professional historians in public life. The analyses show that different considerations compete and work together in the case of all documentaries, and figure at all stages of pre-production, production, and post-produc- tion. But different considerations have particular inuence at different stages in the produc- tion process and thus they are more or less important depending on where in the process the producer puts his emphasis on them. -

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: a Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’S Monster Princess

Yoshioka, Shiro. "Princess Mononoke: A Game Changer." Princess Mononoke: Understanding Studio Ghibli’s Monster Princess. By Rayna Denison. London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2017. 25–40. Bloomsbury Collections. Web. 25 Sep. 2021. <http:// dx.doi.org/10.5040/9781501329753.ch-001>. Downloaded from Bloomsbury Collections, www.bloomsburycollections.com, 25 September 2021, 01:01 UTC. Copyright © Rayna Denison 2018. You may share this work for non-commercial purposes only, provided you give attribution to the copyright holder and the publisher, and provide a link to the Creative Commons licence. 25 Chapter 1 P RINCESS MONONOKE : A GAME CHANGER Shiro Yoshioka If we were to do an overview of the life and works of Hayao Miyazaki, there would be several decisive moments where his agenda for fi lmmaking changed signifi cantly, along with how his fi lms and himself have been treated by the general public and critics in Japan. Among these, Mononokehime ( Princess Mononoke , 1997) and the period leading up to it from the early 1990s, as I argue in this chapter, had a great impact on the rest of Miyazaki’s career. In the fi rst section of this chapter, I discuss how Miyazaki grew sceptical about the style of his fi lmmaking as a result of cataclysmic changes in the political and social situation both in and outside Japan; in essence, he questioned his production of entertainment fi lms featuring adventures with (pseudo- )European settings, and began to look for something more ‘substantial’. Th e result was a grave and complex story about civilization set in medieval Japan, which was based on aca- demic discourses on Japanese history, culture and identity. -

… … Mushi Production

1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … Mushi Production (ancien) † / 1961 – 1973 Tezuka Productions / 1968 – Group TAC † / 1968 – 2010 Satelight / 1995 – GoHands / 2008 – 8-Bit / 2008 – Diomédéa / 2005 – Sunrise / 1971 – Deen / 1975 – Studio Kuma / 1977 – Studio Matrix / 2000 – Studio Dub / 1983 – Studio Takuranke / 1987 – Studio Gazelle / 1993 – Bones / 1998 – Kinema Citrus / 2008 – Lay-Duce / 2013 – Manglobe † / 2002 – 2015 Studio Bridge / 2007 – Bandai Namco Pictures / 2015 – Madhouse / 1972 – Triangle Staff † / 1987 – 2000 Studio Palm / 1999 – A.C.G.T. / 2000 – Nomad / 2003 – Studio Chizu / 2011 – MAPPA / 2011 – Studio Uni / 1972 – Tsuchida Pro † / 1976 – 1986 Studio Hibari / 1979 – Larx Entertainment / 2006 – Project No.9 / 2009 – Lerche / 2011 – Studio Fantasia / 1983 – 2016 Chaos Project / 1995 – Studio Comet / 1986 – Nakamura Production / 1974 – Shaft / 1975 – Studio Live / 1976 – Mushi Production (nouveau) / 1977 – A.P.P.P. / 1984 – Imagin / 1992 – Kyoto Animation / 1985 – Animation Do / 2000 – Ordet / 2007 – Mushi production 1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … 1948 1960 1961 1962 1963 1964 1965 1966 1967 1968 1969 1970 1971 1972 1973 1974 1975 1976 1977 1978 1979 1980 1981 1982 1983 1984 1985 1986 1987 1988 1989 1990 1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 … Tatsunoko Production / 1962 – Ashi Production >> Production Reed / 1975 – Studio Plum / 1996/97 (?) – Actas / 1998 – I Move (アイムーヴ) / 2000 – Kaname Prod. -

Film Noir in Postwar Japan Imogen Sara Smith

FILM NOIR IN POSTWAR JAPAN Imogen Sara Smith uined buildings and neon signs are reflected in the dark, oily surface of a stagnant pond. Noxious bubbles rise to the surface of the water, which holds the drowned corpses of a bicycle, a straw sandal, and a child’s doll. In Akira Kurosawa’s Drunken Angel (1948), this fetid swamp is the center of a disheveled, yakuza-infested Tokyo neighborhood and a symbol of the sickness rotting the soul of postwar Japan. It breeds mosquitos, typhus, and tuberculosis. Around its edges, people mourn their losses, patch their wounds, drown their sorrows, and wrestle with what they have been, what they are, what they want to be. Things looked black for Japan in the aftermath of World War II. Black markets sprang up, as they did in every war-damaged country. Radioactive “black rain” fell after the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Black Spring was the title of a 1953 publication that cited Japanese women’s accounts of rape by Occupation forces. In “Early Japanese Noir” (2014), Homer B. Pettey wrote that in Japanese language and culture, “absence, failure, or being wrong is typified by blackness, as it also indicates the Japanese cultural abhorrence for imperfection or defilement, as in dirt, filth, smut, or being charred.” In films about postwar malaise like Drunken Angel, Kenji Mizoguchi’s Women of the Night (1948), and Masaki Kobayashi’s Black River (1957), filth is everywhere: pestilent cesspools, burnt-out rubble, grungy alleys, garbage-strewn lots, sleazy pleasure districts, squalid shacks, and all the human misery and depravity that go along with these settings. -

A Study of Akira Kurosawa's Ikiru on Its Fiftieth Anniversary

PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION THROUGH AN ENCOUNTER WITH DEATH: A STUDY OF AKIRA KUROSAWA’S IKIRU ON ITS FIFTIETH ANNIVERSARY Francis G. Lu, M.D. San Francisco, California ABSTRACT: Akira Kurosawa’s film 1952 Ikiru (the intransitive verb ‘‘to live’’ in Japanese) presents the viewer with a seeming paradox: a heightened awareness of one’s mortality can lead to living a more authentic and meaningful life. While confronting these existential issues, our hero Watanabe traces the path of the Hero’s Journey as described by the mythologist Joseph Campbell among others. Simultaneous to this outward arc, Watanabe experiences an inward arc of transformation of consciousness taking him from the individual persona to the transpersonal. Kurosawa skillfully blends aesthetic concepts and sensibilities both Western (Dostoyevsky, Tolstoy, Goethe’s Faust) and Eastern (Noh, Zen Buddhist) to create one of the greatest of cinematic masterworks. PROLOGUE ‘‘Awareness of death is the very bedrock of the path. Until you have developed this awareness, all other practices are obstructed.’’ —The Dalai Lama ‘‘Whoever rightly understands and celebrates death, at the same time magnifies life.’’ —Rainer Maria Rilke ‘‘As long as you do not know how to die and come to life again, you are but a poor guest on this dark earth.’’ —Johann Wolfgang von Goethe ‘‘Eternity is in love with the productions of time.’’ —William Blake ‘‘Sometimes I think of my death. I think of ceasing to be ... and it is from these thoughts that Ikiru came.’’ —Akira Kurosawa INTRODUCTION Ikiru is a 1952 Japanese film directed by Akira Kurosawa, who is widely acknowledged as one of the cinema’s greatest directors; the screenplay was written by Kurosawa, Shinobu Hashimoto and Hideo Oguni. -

Language Lab Video Catalog

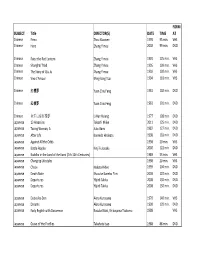

FORM SUBJECT Title DIRECTOR(S) DATE TIME AT Chinese Ermo Zhou Xiaowen 1995 95 min. VHS Chinese Hero Zhang Yimou 2002 99 min. DVD Chinese Raise the Red Lantern Zhang Yimou 1991 125 min. VHS Chinese Shanghai Triad Zhang Yimou 1995 109 min. VHS Chinese The Story of Qiu Ju Zhang Yimou 1992 100 min. VHS Chinese Vive L'Amour Ming‐liang Tsai 1994 118 min. VHS Chinese 紅樓夢 Yuan Chiu Feng 1961 102 min. DVD Chinese 紅樓夢 Yuan Chiu Feng 1961 101 min. DVD Chinese 金玉良緣紅樓夢 Li Han Hsiang 1977 108 min. DVD Japanese 13 Assassins Takashi Miike 2011 125 min. DVD Japanese Taxing Woman, AJuzo Itami 1987 127 min. DVD Japanese After Life Koreeda Hirokazu 1998 118 min. DVD Japanese Against All the Odds 1998 20 min. VHS Japanese Battle Royale Kinji Fukasaku 2000 122 min. DVD Japanese Buddha in the Land of the Kami (7th‐12th Centuries) 1989 53 min. VHS Japanese Changing Lifestyles 1998 20 min. VHS Japanese Chaos Nakata Hideo 1999 104 min. DVD Japanese Death Note Shusuke Kaneko Film 2003 120 min. DVD Japanese Departures Yôjirô Takita 2008 130 min. DVD Japanese Departures Yôjirô Takita 2008 130 min. DVD Japanese Dodes'ka‐Den Akira Kurosawa 1970 140 min. VHS Japanese Dreams Akira Kurosawa 1990 120 min. DVD Japanese Early English with Doraemon Kusuba Kôzô, Shibayama Tsutomu 1988 VHS Japanese Grave of the Fireflies Takahata Isao 1988 88 min. DVD FORM SUBJECT Title DIRECTOR(S) DATE TIME AT Japanese Happiness of the Katakuris Takashi Miike 2001 113 min. DVD Japanese Ikiru Akira Kurosawa 1952 143 min. -

Kierkegaard, Literature, and the Arts

Kierke gaard, Literature, and the Arts Engraving, ca. 1837, by Carl Strahlheim showing the Gendarmenmarkt in Berlin, with what was then the Schauspielhaus, or Theater (center)— now the concert house of the Konzerthausorchester Berlin— flanked by the German Cathedral (left) and the French Cathedral (right). Pictured in the background to the immediate right of the theater is the building, still standing today, in which Kierkegaard lodged during his four stays in Berlin, in 1841– 42, 1843, 1845, and 1846. It was there, as noted by a plaque outside, that Kierkegaard wrote the first drafts of Either/Or, Repetition, and Fear and Trembling. Kierkegaard, Literature, and the Arts Edited by Eric Ziolkowski northwestern university press evanston, illinois Northwestern University Press www.nupress.northwestern.edu Copyright © 2018 by Northwestern University Press. Published 2018. All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Library of Congress Cataloging- in- Publication Data Names: Ziolkowski, Eric Jozef, 1958– editor. Title: Kierkegaard, literature, and the arts / edited by Eric Ziolkowski. Description: Evanston, Illinois : Northwestern University Press, 2018. | Includes index. Identifiers: LCCN 2017029795 | ISBN 9780810135970 (cloth : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780810135963 (pbk. : alk. paper) | ISBN 9780810135987 (e-book) Subjects: LCSH: Kierkegaard, Søren, 1813–1855. | Kierkegaard, Søren, 1813– 1855—Aesthetics. | Literature—Philosophy. | Music and philosophy. | Art and philosophy. | Performing arts—Philosophy. Classification: LCC B4377 .K4558 2018 | DDC 198.9—dc23 LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017029795 Except where otherwise noted, this book is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. To view a copy of this license, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.