Molecular Pathology of ALS: What We Currently Know and What Important Information Is Still Missing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Efficacy of Texture and Color Enhancement Imaging In

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Efcacy of Texture and Color Enhancement Imaging in visualizing gastric mucosal atrophy and gastric neoplasms Tsubasa Ishikawa1, Tomoaki Matsumura1*, Kenichiro Okimoto1, Ariki Nagashima1, Wataru Shiratori1, Tatsuya Kaneko1, Hirotaka Oura1, Mamoru Tokunaga1, Naoki Akizue1, Yuki Ohta1, Keiko Saito1, Makoto Arai1,2, Jun Kato1 & Naoya Kato1 In 2020, Olympus Medical Systems Corporation introduced the Texture and Color Enhancement Imaging (TXI) as a new image-enhanced endoscopy. This study aimed to evaluate the visibility of neoplasms and mucosal atrophy in the upper gastrointestinal tract through TXI. We evaluated 72 and 60 images of 12 gastric neoplasms and 20 gastric atrophic/nonatrophic mucosa, respectively. The visibility of gastric mucosal atrophy and gastric neoplasm was assessed by six endoscopists using a previously reported visibility scale (1 = poor to 4 = excellent). Color diferences between gastric mucosal atrophy and nonatrophic mucosa and between gastric neoplasm and adjacent areas were assessed using the International Commission on Illumination L*a*b* color space system. The visibility of mucosal atrophy and gastric neoplasm was signifcantly improved in TXI mode 1 compared with that in white-light imaging (WLI) (visibility score: 3.8 ± 0.5 vs. 2.8 ± 0.9, p < 0.01 for mucosal atrophy; visibility score: 2.8 ± 1.0 vs. 2.0 ± 0.9, p < 0.01 for gastric neoplasm). Regarding gastric atrophic and nonatrophic mucosae, TXI mode 1 had a signifcantly greater color diference than WLI (color diferences: 14.2 ± 8.0 vs. 8.7 ± 4.2, respectively, p < 0.01). TXI may be a useful observation modality in the endoscopic screening of the upper gastrointestinal tract. -

Gas Gangrene Infection of the Eyes and Orbits

Br J Ophthalmol: first published as 10.1136/bjo.69.2.143 on 1 February 1985. Downloaded from British Journal of Ophthalmology, 1985, 69, 143-148 Gas gangrene infection of the eyes and orbits GERARD W CROCK,' WILSON J HERIOT,' PATTABIRAMAN JANAKIRAMAN,' AND JOHN M WEINER2 From the 'Department of Ophthalmology, University ofMelbourne, and the2C H Greer Pathology Laboratory, the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital, East Melbourne, Australia SUMMARY The literature on Clostridium perfringens infections is reviewed up to 1983. An additional case is reported with bilateral clostridial infections of the eye and orbit. One eye followed the classical course of relentless panophthalmitis, amaurosis, and orbital cellulitis ending in enucleation. The second eye contained intracameral mud and gas bubbles that were removed by vitrectomy instrumentation. Subsequent removal of the toxic cataract resulted in a final aided visual acuity of 6/18, N8. This is the third report of a retained globe, and we believe the only known case where the patient was left with useful vision. Clostridium perfringens is a ubiquitous Gram- arms, chest, and abdomen. He was admitted to a positive bacillus found in soil and bowel flora. It is the general hospital, where he was examined under most common of four clostridia species identified in anaesthesia, and his injuries were attended to. copyright. cases of gas gangrene in man.' All species are obligate Ocular findings. The right cornea and anterior anaerobes and are usually saprophytic rather than chamber were intact. There was a scleral laceration pathogenic. Clostridium perfringens is a feared con- over the superonasal area of the pars plana with taminant of limb injuries and may result in death due vitreous prolapse. -

Pain Improvement in Parkinson's Disease Patients Treated

Journal of Personalized Medicine Article Pain Improvement in Parkinson’s Disease Patients Treated with Safinamide: Results from the SAFINONMOTOR Study Diego Santos García 1,* , Rosa Yáñez Baña 2, Carmen Labandeira Guerra 3, Maria Icíar Cimas Hernando 4, Iria Cabo López 5 , Jose Manuel Paz González 1, Maria Gema Alonso Losada 3, Maria José Gonzalez Palmás 5, Carlos Cores Bartolomé 1 and Cristina Martínez Miró 1 1 Department of Neurology, CHUAC, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de A Coruña, 15006 A Coruña, Spain; [email protected] (J.M.P.G.); [email protected] (C.C.B.); [email protected] (C.M.M.) 2 Department of Neurology, CHUO, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Ourense, 32005 Ourense, Spain; [email protected] 3 Department of Neurology, CHUVI, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Vigo, 36213 Vigo, Spain; [email protected] (C.L.G.); [email protected] (M.G.A.L.) 4 Hospital de Povisa, 36211 Vigo, Spain; [email protected] 5 Department of Neurology, CHOP, Complejo Hospitalario Universitario de Pontevedra, 36002 Pontevedra, Spain; [email protected] (I.C.L.); [email protected] (M.J.G.P.) * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +34-646-173-341 Citation: Santos García, D.; Yáñez Abstract: Background and objective: Pain is a frequent and disabling symptom in Parkinson’s disease Baña, R.; Labandeira Guerra, C.; (PD) patients. Our aim was to analyze the effectiveness of safinamide on pain in PD patients from Cimas Hernando, M.I.; Cabo López, the SAFINONMOTOR (an open-label study of the effectiveness of SAFInamide on NON-MOTOR I.; Paz González, J.M.; Alonso Losada, symptoms in Parkinson´s disease patients) study. -

AMYOTROPHIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS Spin21 (1)

AMYOTROPHIC LATERAL SCLEROSIS Spin21 (1) Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis (ALS) Synonyms: CHARCOT'S DISEASE (in Europe), LOU GEHRIG'S DISEASE (in USA) Last updated: April 22, 2019 ETIOPATHOPHYSIOLOGY, PATHOLOGY .................................................................................................. 1 GENETICS ............................................................................................................................................... 3 EPIDEMIOLOGY ........................................................................................................................................ 3 Genetics ............................................................................................................................................ 3 CLINICAL FEATURES ............................................................................................................................... 3 EL ESCORIAL WORLD FEDERATION OF NEUROLOGY CRITERIA .............................................................. 4 CLINICAL COURSE & PROGNOSIS ........................................................................................................... 4 VARIANTS .............................................................................................................................................. 5 DIAGNOSIS................................................................................................................................................ 5 TREATMENT ............................................................................................................................................ -

Voice of the Patient Report for Spinal Muscular Atrophy

V OICE OF THE PATIENT REPORT A summary report resulting from an Externally-Led Patient Focused Drug Development Meeting reflecting the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Patient-Focused Drug Development Initiative Spinal Muscular Atrophy (SMA) Externally Led Public Meeting: April 18, 2017 Report Date: January 10, 2018 Title of Resource: The Voice of the Patient Report for Spinal Muscular Atrophy Authors: Contributors to the collection of the information and development of the document are: Cure SMA: Rosangel Cruz, Megan Lenz, Lisa Belter, Kenneth Hobby, Jill Jarecki Medical Writer: Theo Smart Cruz, Lenz, Belter, Hobby, and Jarecki are all employees of Cure SMA and have no disclosures. Cure SMA has received funding from certain companies for work on projects unrelated to the Patient-Focused Drug Development meeting. Funding Received: The report was funded by grants received from the SMA Industry Collaboration to support Cure SMA’s production and execution of the Externally-Led Patient-Focused Drug Development initiative for SMA and the engagement of an outside medical writing professional to assist in the development, editing, and production of The Voice of the Patient report for SMA. The members of the SMA Industry Collaboration are Astellas Pharmaceuticals, AveXis, Inc., Biogen, Genentech/Roche Pharmaceuticals, Cytokinetics Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals, and Ionis Pharmaceuticals, Inc. Version Date: January 10, 2018 Revision Statement: This resource document has not been revised and/or modified in any way after January 10, 2018. Statement of Use: Cure SMA has the necessary permissions to submit the “The Voice of the Patient for SMA” report to the U.S. FDA. -

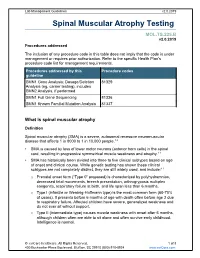

Spinal Muscular Atrophy Testing

Lab Management Guidelines v2.0.2019 Spinal Muscular Atrophy Testing MOL.TS.225.B v2.0.2019 Procedures addressed The inclusion of any procedure code in this table does not imply that the code is under management or requires prior authorization. Refer to the specific Health Plan's procedure code list for management requirements. Procedures addressed by this Procedure codes guideline SMN1 Gene Analysis; Dosage/Deletion 81329 Analysis (eg, carrier testing), includes SMN2 Analysis, if performed SMN1 Full Gene Sequencing 81336 SMN1 Known Familial Mutation Analysis 81337 What is spinal muscular atrophy Definition Spinal muscular atrophy (SMA) is a severe, autosomal recessive neuromuscular disease that affects 1 in 8000 to 1 in 10,000 people.1,2 SMA is caused by loss of lower motor neurons (anterior horn cells) in the spinal cord, resulting in progressive symmetrical muscle weakness and atrophy.1-3 SMA has historically been divided into three to five clinical subtypes based on age of onset and clinical course. While genetic testing has shown these clinical subtypes are not completely distinct, they are still widely used, and include:1-3 o Prenatal onset form (“Type 0” proposed) is characterized by polyhydramnios, decreased fetal movements, breech presentation, arthrogryposis multiplex congenita, respiratory failure at birth, and life span less than 6 months. o Type I (infantile or Werdnig-Hoffmann type) is the most common form (60-70% of cases). It presents before 6 months of age with death often before age 2 due to respiratory failure. Affected children have severe, generalized weakness and do not ever sit without support. -

ALS and Other Motor Neuron Diseases Can Represent Diagnostic Challenges

Review Article Address correspondence to Dr Ezgi Tiryaki, Hennepin ALS and Other Motor County Medical Center, Department of Neurology, 701 Park Avenue P5-200, Neuron Diseases Minneapolis, MN 55415, [email protected]. Ezgi Tiryaki, MD; Holli A. Horak, MD, FAAN Relationship Disclosure: Dr Tiryaki’s institution receives support from The ALS Association. Dr Horak’s ABSTRACT institution receives a grant from the Centers for Disease Purpose of Review: This review describes the most common motor neuron disease, Control and Prevention. ALS. It discusses the diagnosis and evaluation of ALS and the current understanding of its Unlabeled Use of pathophysiology, including new genetic underpinnings of the disease. This article also Products/Investigational covers other motor neuron diseases, reviews how to distinguish them from ALS, and Use Disclosure: Drs Tiryaki and Horak discuss discusses their pathophysiology. the unlabeled use of various Recent Findings: In this article, the spectrum of cognitive involvement in ALS, new concepts drugs for the symptomatic about protein synthesis pathology in the etiology of ALS, and new genetic associations will be management of ALS. * 2014, American Academy covered. This concept has changed over the past 3 to 4 years with the discovery of new of Neurology. genes and genetic processes that may trigger the disease. As of 2014, two-thirds of familial ALS and 10% of sporadic ALS can be explained by genetics. TAR DNA binding protein 43 kDa (TDP-43), for instance, has been shown to cause frontotemporal dementia as well as some cases of familial ALS, and is associated with frontotemporal dysfunction in ALS. Summary: The anterior horn cells control all voluntary movement: motor activity, res- piratory, speech, and swallowing functions are dependent upon signals from the anterior horn cells. -

Taste and Smell Disorders in Clinical Neurology

TASTE AND SMELL DISORDERS IN CLINICAL NEUROLOGY OUTLINE A. Anatomy and Physiology of the Taste and Smell System B. Quantifying Chemosensory Disturbances C. Common Neurological and Medical Disorders causing Primary Smell Impairment with Secondary Loss of Food Flavors a. Post Traumatic Anosmia b. Medications (prescribed & over the counter) c. Alcohol Abuse d. Neurodegenerative Disorders e. Multiple Sclerosis f. Migraine g. Chronic Medical Disorders (liver and kidney disease, thyroid deficiency, Diabetes). D. Common Neurological and Medical Disorders Causing a Primary Taste disorder with usually Normal Olfactory Function. a. Medications (prescribed and over the counter), b. Toxins (smoking and Radiation Treatments) c. Chronic medical Disorders ( Liver and Kidney Disease, Hypothyroidism, GERD, Diabetes,) d. Neurological Disorders( Bell’s Palsy, Stroke, MS,) e. Intubation during an emergency or for general anesthesia. E. Abnormal Smells and Tastes (Dysosmia and Dysgeusia): Diagnosis and Treatment F. Morbidity of Smell and Taste Impairment. G. Treatment of Smell and Taste Impairment (Education, Counseling ,Changes in Food Preparation) H. Role of Smell Testing in the Diagnosis of Neurodegenerative Disorders 1 BACKGROUND Disorders of taste and smell play a very important role in many neurological conditions such as; head trauma, facial and trigeminal nerve impairment, and many neurodegenerative disorders such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson Disorders, Lewy Body Disease and Frontal Temporal Dementia. Impaired smell and taste impairs quality of life such as loss of food enjoyment, weight loss or weight gain, decreased appetite and safety concerns such as inability to smell smoke, gas, spoiled food and one’s body odor. Dysosmia and Dysgeusia are very unpleasant disorders that often accompany smell and taste impairments. -

Short Course 10 Metaplasia in The

0 3: 436-446 Rev Esp Patot 1999; Vol. 32, N © Prous Science, SA. © Sociedad Espajiola de Anatomia Patot6gica Short Course 10 © Sociedad Espafiola de Citologia Metaplasia in the gut Chairperson: NA. Wright, UK. Co-chairpersons: G. Coggi, Italy and C. Cuvelier, Belgium. Overview of gastrointestinal metaplasias only in esophagus but also in the duodenum, intestine, gallbladder and even in the pancreas. Well established is columnar metaplasia J. Stachura of esophageal squamous epithelium. Its association with increased risk of esophageal cancer is widely recognized. Recent develop- Dept. of Pathomorphology, Jagiellonian University ments have suggested, however, that only the intestinal type of Faculty of Medicine, Krakdw, Poland. metaplastic epithelium (classic Barrett’s esophagus) predisposes to cancer. Another field of studies is metaplasia in the short seg- ment at the esophago-cardiac junction, its association with Metaplasia is a reversible change in which one aduit cell type is Helicobacter pylon infection and/or reflux disease and intestinal replaced by another. It is always associated with some abnormal metaplasia in the cardiac and fundic areas. stimulation of tissue growth, tissue regeneration or excessive hor- Studies on gastric mucosa metaplasia could be divided into monal stimulation. Heterotopia, on the other hand, takes place dur- those concerned with pathogenesis and detailed structural/func- ing embryogenesis and is usually supposed not to be associated tional features and those concerned with clinical significance. with tissue damage. Pancreatic acinar cell clusters in pediatric gas- We know now that gastric mucosa may show not only complete tric mucosa form another example of aberrant cell differentiation. and incomplete intestinal metaplasia but also others such as ciliary Metaplasia is usually divided into epithelial and connective tis- and pancreatic metaplasia. -

Approach to a Patient with Hemiplegia and Monoplegia

CHAPTER Approach to a Patient with Hemiplegia and Monoplegia 27 Sudhir Kumar, Subhash Kaul INTRODUCTION 4. Injury to multiple cervical nerve roots. Monoplegia and hemiplegia are common neurological 5. Functional or psychogenic. symptoms in patients presenting to the emergency department as well as outpatient department. Insidious onset, gradually progressive monoplegia affecting lower limb can be caused by the following Monoplegia refers to weakness of one limb (either arm or conditions: leg) and hemiplegia refers to weakness of one arm and leg on the same side of body (either left or right side). 1. Tumor of the contralateral frontal lobe. There are a variety of underlying causes for monoplegia 2. Tumor of spinal cord at thoracic or lumbar level. and hemiplegia. The causes differ in different age groups. 3. Chronic infection of brain (frontal lobe) or spinal The causes also differ depending on the onset, progression cord (thoracic or lumbar level), such as tuberculous. and duration of weakness. Therefore, one needs to adopt a systematic approach during history taking and 4. Lumbosacral-plexopathy, due to diabetes mellitus. examination in order to arrive at the correct diagnosis. Insidious onset, gradually progressive monoplegia, Appropriate investigations after these would confirm the affecting upper limb, can be caused by one of the following diagnosis. conditions: The aim of this chapter is to systematically look at the 1. Tumor of the contralateral parietal lobe. differential diagnosis of monoplegia and hemiplegia and outline the approach needed to pinpoint the exact 2. Compressive lesion (tumor, large disc, etc) in underlying cause. cervical cord region. 3. Chronic infection of the brain (parietal lobe) or APPROACH TO THE DIAGNOSIS OF MONOPLEGIA spinal cord (cervical region), such as tuberculous. -

Additional Antidepressant Pharmacotherapies According to A

orders & is T D h e n r Werner and Coveñas, Brain Disord Ther 2016, 5:1 i a a p r y B Brain Disorders & Therapy DOI: 10.4172/2168-975X.1000203 ISSN: 2168-975X Review Article Open Access Additional Antidepressant Pharmacotherapies According to a Neural Network Felix-Martin Werner1, 2* and Rafael Coveñas2 1Higher Vocational School of Elderly Care and Occupational Therapy, Euro Academy, Pößneck, Germany 2Laboratory of Neuroanatomy of the Peptidergic Systems, Institute of Neurosciences of Castilla y León (INCYL), University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain Abstract Major depression, a frequent psychiatric disease, is associated with neurotransmitter alterations in the midbrain, hypothalamus and hippocampus. Deficiency of postsynaptic excitatory neurotransmitters such as dopamine, noradrenaline and serotonin and a surplus of presynaptic inhibitory neurotransmitters such as GABA and glutamate (mainly a postsynaptic excitatory and partly a presynaptic inhibitory neurotransmitter), can be found in the involved brain regions. However, neuropeptide alterations (galanin, neuropeptide Y, substance P) also play an important role in its pathogenesis. A neural network is described, including the alterations of neuroactive substances at specific subreceptors. Currently, major depression is treated with monoamine reuptake inhibitors. An additional therapeutic option could be the administration of antagonists of presynaptic inhibitory neurotransmitters or the administration of agonists/antagonists of neuropeptides. Keywords: Acetylcholine; Bupropion; Dopamine; GABA; Galanin; in major depression and to point out the coherence between single Glutamate; Hippocampus; Hhypothalamus; Major depression; neuroactive substances and their corresponding subreceptors. A Midbrain; Neural network; Neuropeptide Y; Noradrenaline; Serotonin; question should be answered, whether a multimodal pharmacotherapy Substance P with an agonistic or antagonistic effect at several subreceptors is higher than the current conventional antidepressant treatment. -

Retrograde Transport of Plasticity Signals in Ap/Ysia Sensory Neurons Following Axonal Injury

The Journal of Neuroscience, January 1995, 15(i): 439-448 Retrograde Transport of Plasticity Signals in Ap/ysia Sensory Neurons Following Axonal Injury John D. Gunstream, Gilbert A. Castro, and Edgar T. Walters Department of Physiology and Cell Biology, University of Texas-Houston Medical School, Houston, Texas 77225 Following injury to their peripheral branches, mechanosen- 1990). Becausemany of these alterations involve changesin sory neurons in Aplysia display long-term plasticity that is geneexpression and protein synthesis(e.g., Watson, 1968; Her- expressed as soma hyperexcitability, synaptic facilitation, degen et al., 1992; Haas et al., 1993) pathways must exist that and neurite outgrowth. To investigate the nature of signals inform the nucleus of cellular damage occurring far from the that convey information about distant axonal injury, we have soma. Many potential injury signalsexist, which may act singly investigated the development of injury-induced soma hy- or in concert (e.g., Cragg, 1970; Lieberman, 1971; Aldskogius perexcitability in two in vitro preparations. In isolated gan- et al., 1992). However, it is useful to distinguish two classesof glia, proximal nerve crush caused hyperexcitability to ap- axonal signals (e.g., Wu et al., 1993). Negative injury signals pear sooner than did distal crush, and the difference in result from an interruption of retrograde transport of chemical development of hyperexcitability indicated that the injury signals,such as trophic substances,that normally are continu- signal moved at a rate (36 mm/d) similar to previously re- ously conveyed from distal parts of an uninjured axon to the ported rates of retrograde axonal transport in this animal.