Arteriosclerosis: Facts and Fancy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Threshold for Diagnosis of Stenosis Or Thrombosis Within Six Months of Access Flow Measurement in Arteriovenous Fistulae

J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 3264–3269, 2003 Best Threshold for Diagnosis of Stenosis or Thrombosis within Six Months of Access Flow Measurement in Arteriovenous Fistulae MARCELLO TONELLI,*†‡ GIAN S. JHANGRI,§ DAVID J. HIRSCH,ʈ¶ JOANNE MARRYATT,¶ PAULA MOSSOP,¶ COLLEEN WILE,¶ and KAILASH K. JINDAL* *Department of Medicine, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada; †Department of Critical Care, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada; ‡Institute of Health Economics, Edmonton, Canada; §Department of Public Health Sciences, University of Alberta, Edmonton, Canada; ʈDepartment of Medicine, Dalhousie University, Halifax, Canada; and ¶Queen Elizabeth II Health Sciences Centre, Halifax, Canada Abstract. Canadian clinical practice guidelines recommend within 6 mo, and both seemed superior to Ͻ400 ml/min. performing angiography when access blood flow (Qa) is Ͻ500 However, the frequency of the composite definition of stenosis ml/min in native vessel arteriovenous fistulae (AVF), but data among AVF with Qa between 500 and 600 ml/min was only 6 on the value of Qa that best predicts stenosis are sparse. (25%) of 24, as compared with 58 (76%) of 76 when Qa was Because correction of stenosis in AVF improves patency rates, Ͻ500 ml/min. This suggests that most lesions that would be this issue seems worthy of investigation. Receiver-operating found using a threshold of Ͻ600 ml/min occurred in AVF with characteristic curves were constructed to examine the relation- Qa Ͻ500 ml/min and that the small gain in sensitivity associ- ship between different threshold values of Qa and stenosis in ated with the Ͻ600-ml/min threshold would be outweighed by 340 patients with AVF. -

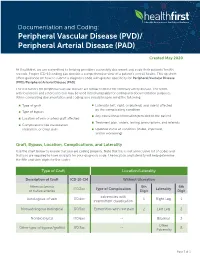

Documentationand Coding Tips: Peripheral Vascular Disease

Documentation and Coding: Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD)/ Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD) Created May 2020 At Healthfirst, we are committed to helping providers accurately document and code their patients’ health records. Proper ICD-10 coding can provide a comprehensive view of a patient’s overall health. This tip sheet offers guidance on how to submit a diagnosis code with greater specificity for Peripheral Vascular Disease (PVD)/Peripheral Arterial Disease (PAD). The risk factors for peripheral vascular disease are similar to those for coronary artery disease. The terms arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis may be used interchangeably for coding and documentation purposes. When completing documentation and coding, you should keep in mind the following: Type of graft Laterality (left, right, or bilateral) and side(s) affected by the complicating condition Type of bypass Any educational information provided to the patient Location of vein or artery graft affected Treatment plan, orders, testing, prescriptions, and referrals Complications like claudication, ulceration, or chest pain Updated status of condition (stable, improved, and/or worsening) Graft, Bypass, Location, Complications, and Laterality Use the chart below to ensure that you are coding properly. Note that this is not an inclusive list of codes and that you are required to have six digits for your diagnosis code. The location and laterality will help determine the fifth and sixth digits for the codes. Type of Graft Location/Laterality Description of Graft ICD-10-CM Without -

Everything I Need to Know About Renal Artery Stenosis

Patient Information Renal Services Everything I need to know about renal artery stenosis What is renal artery stenosis? Renal artery stenosis is the narrowing of the main blood vessel running to one or both of your kidneys. Why does renal artery stenosis occur? It is part of the process of arteriosclerosis (hardening of the arteries), that develops in very many of us as we get older. As well as becoming thicker and harder, the arteries develop fatty deposits in their walls which can cause narrowing. If the kidneys are affected there is generally also arterial disease (narrowing of the arteries) in other parts of the body, and often a family history of heart attack or stroke, or poor blood supply to the lower legs. Arteriosclerosis is a consequence of fat in our diet, combined with other factors such as smoking, high blood pressure and genetic factors inherited, it may develop faster if you have diabetes. What are the symptoms? You may have fluid retention, where the body holds too much water and this can cause breathlessness, however often there are no symptoms. The arterial narrowing does not cause pain, and urine is passed normally. As a result this is usually a problem we detect when other tests are done, for example, routine blood test to measure how well your kidneys are working. What are the complications of renal artery stenosis? Kidney failure, if the kidneys have a poor blood supply, they may stop working. This can occur if the artery blocks off suddenly or more gradually if there is serious narrowing. -

Hereditary Hemorrhagic Telangiectasia: Diagnosis and Management From

REVIEW ARTICLE Hereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia: Ferrata Storti diagnosis and management from Foundation the hematologist’s perspective Athena Kritharis,1 Hanny Al-Samkari2 and David J Kuter2 1Division of Blood Disorders, Rutgers Cancer Institute of New Jersey, New Brunswick, NJ and 2Hematology Division, Massachusetts General Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA, USA ABSTRACT Haematologica 2018 Volume 103(9):1433-1443 ereditary hemorrhagic telangiectasia (HHT), also known as Osler- Weber-Rendu syndrome, is an autosomal dominant disorder that Hcauses abnormal blood vessel formation. The diagnosis of hered- itary hemorrhagic telangiectasia is clinical, based on the Curaçao criteria. Genetic mutations that have been identified include ENG, ACVRL1/ALK1, and MADH4/SMAD4, among others. Patients with HHT may have telangiectasias and arteriovenous malformations in various organs and suffer from many complications including bleeding, anemia, iron deficiency, and high-output heart failure. Families with the same mutation exhibit considerable phenotypic variation. Optimal treatment is best delivered via a multidisciplinary approach with appropriate diag- nosis, screening and local and/or systemic management of lesions. Antiangiogenic agents such as bevacizumab have emerged as a promis- ing systemic therapy in reducing bleeding complications but are not cur- ative. Other pharmacological agents include iron supplementation, antifibrinolytics and hormonal treatment. This review discusses the biol- ogy of HHT, management issues that face -

Report on the Cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms And

Report on the Cooperative Study of Intracranial Aneurysms and Subarachnoid Hemorrhage SECTION VIII, Part I Results of the Treatment of Intracranial Aneurysms by Occlusion of the Carotid Artery in the Neck HIRO NISHIOKA, M.D.* Introduction In a late postoperative study of retinal artery CCLUSION of the cervical portion of the pressures in 13 patients with carotid liga- carotid artery has been employed tion, Christiansson '6~ found eight patients O since 1885 as a definitive treatment who had maintained pressure drops of 20 per for intracranial aneurysm. The resultant re- cent or more over a period of from 1 to 13 duction of intra-arterial pressure is expected years. The observation that there was stasis to reduce the likelihood of subsequent of blood within the aneuwsmal sac after hemorrhage. The alteration of blood flow carotid occlusion was made at angiography characteristics within the aneurysmal sac by Eeker and Riemenschneider '51. During may encourage thrombosis with organization digital carotid occlusion, they found that and fibrosis, which would strengthen the wall Diodrast remained within the sac for over a or obliterate the sac. That pressure can be minute, and, in the same patient, angiog- reduced effectively in the internal carotid raphy performed one week after partial artery by proximal internal or common ca- occlusion of the common carotid by a tan- rotid occlusion has been substantiated amply talum clip showed no filling of the aneurysm. by the works of many authors. However, Aneurysms may decrease visibly in size or pressure reductions distal to the bifurcation become progressively thrombosed after ca- of the internal carotid artery following ca- rotid ligation. -

Peripheral Arterial Disease

SEMINAR Seminar Peripheral arterial disease Kenneth Ouriel Lower extremity peripheral arterial disease (PAD) most frequently presents with pain during ambulation, which is known as “intermittent claudication”. Some relief of symptoms is possible with exercise, pharmacotherapy, and cessation of smoking. The risk of limb-loss is overshadowed by the risk of mortality from coexistent coronary artery and cerebrovascular atherosclerosis. Primary therapy should be directed at treating the generalised atherosclerotic process, managing lipids, blood sugar, and blood pressure. By contrast, the risk of limb-loss becomes substantial when there is pain at rest, ischaemic ulceration, or gangrene. Interventions such as balloon angioplasty, stenting, and surgical revascularisation should be considered in these patients with so-called “critical limb ischaemia”. The choice of the intervention is dependent on the anatomy of the stenotic or occlusive lesion; percutaneous interventions are appropriate when the lesion is focal and short but longer lesions must be treated with surgical revascularisation to achieve acceptable long-term outcome. Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) comprises those entities ankle systolic pressure measured with a blood pressure at which result in obstruction to blood flow in the arteries, the malleolar level by the higher of the two brachial exclusive of the coronary and intracranial vessels. pressures. Defining PAD by an ankle-brachial index of Although the definition of PAD technically includes less than 0·95, a frequency of 6·9% was observed in problems within the extracranial carotid circulation, the patients aged 45–74 years, only 22% of whom had upper extremity arteries, and the mesenteric and renal symptoms.5 The frequency of intermittent claudication circulation, we will focus on chronic arterial occlusive increases dramatically with advancing age, ranging from disease in the arteries to the legs. -

Hypertension and Coronary Heart Disease

Journal of Human Hypertension (2002) 16 (Suppl 1), S61–S63 2002 Nature Publishing Group All rights reserved 0950-9240/02 $25.00 www.nature.com/jhh Hypertension and coronary heart disease E Escobar University of Chile, Santiago, Chile The association of hypertension and coronary heart atherosclerosis, damage of arterial territories other than disease is a frequent one. There are several patho- the coronary one, and of the extension and severity of physiologic mechanisms which link both diseases. coronary artery involvement. It is important to empha- Hypertension induces endothelial dysfunction, exacer- sise that complications and mortality of patients suffer- bates the atherosclerotic process and it contributes to ing a myocardial infarction are greater in hypertensive make the atherosclerotic plaque more unstable. Left patients. Treatment should be aimed to achieve optimal ventricular hypertrophy, which is the usual complication values of blood pressure, and all the strategies to treat of hypertension, promotes a decrease of ‘coronary coronary heart disease should be considered on an indi- reserve’ and increases myocardial oxygen demand, vidual basis. both mechanisms contributing to myocardial ischaemia. Journal of Human Hypertension (2002) 16 (Suppl 1), S61– From a clinical point of view hypertensive patients S63. DOI: 10.1038/sj/jhh/1001345 should have a complete evaluation of risk factors for Keywords: hypertension; hypertrophy; coronary heart disease There is a strong and frequent association between arterial hypertension.8 Hypertension is frequently arterial hypertension and coronary heart disease associated to metabolic disorders, such as insulin (CHD). In the PROCAM study, in men between 40 resistance with hyperinsulinaemia and dyslipidae- and 66 years of age, the prevalence of hypertension mia, which are additional risk factors of atheroscler- in patients who had a myocardial infarction was osis.9 14/1000 men in a follow-up of 4 years. -

Peripheral Arterial Disease

Peripheral arterial disease (Poor blood supply) Information sheet What is it? Peripheral arterial disease (PAD) is the narrowing of one or more arteries (blood vessels). It affects arteries that take blood to the legs, reducing the oxygen that gets to the foot that helps keep the tissues healthy. Also known as 'peripheral vascular disease' and sometimes called 'hardening of the arteries'. What causes it? The narrowing of the arteries is caused by atheroma. Atheroma is like fatty patches or 'plaques' that develop inside the lining of arteries. A patch of atheroma starts quite small, and causes no problems at first. Over the years it can thicken up and start to affect the blood flow through the arteries. (It is a bit like limescale that forms on the inside of water pipes). What are the symptoms? The typical symptom is like a ‘cramping’ sensation in the calves when walking a short distance. It is called 'intermittent claudication'. The pain is relieved when you stop walking. In more serious cases, cramp can be felt in the calf muscles during rest and at night. How can I help prevent it? The best way to help prevent this is to: Stop smoking Exercise regularly Maintain a healthy weight Eat a healthy diet Limit the amount of alcohol you drink (Contact your practice nurse for any further advice on the above) Take care of your feet www.oxleas.nhs.uk How do I take care of my feet? Try not to injure your feet as this can lead to an ulcer or infection developing more easily if the blood supply to the feet is reduced. -

A Successful Intra-Pleural Fibrinolytic Therapy with Alteplase in a Patient with Empyematous Multiloculated Chylothorax

CASE REPORT East J Med 24(3): 379-382, 2019 DOI: 10.5505/ejm.2019.72621 A Successful Intra-Pleural Fibrinolytic Therapy With Alteplase in A Patient with Empyematous Multiloculated Chylothorax Mohamed Faisal1*, Rayhan Amiseno1, Nurashikin Mohammad2 1Respiratory Unit, Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia Medical Centre, Malaysia 2Medical Department, Universiti Sains Malaysia ABSTRACT Chylothorax is a collection of chyle in the pleural cavity resulting from leakage of lymphatic vessels, usually from the thoracic duct. In majority of cases, chylothorax is a bacteriostatic pleural effusion. Incidence of infected or even empyematous chylothorax are not common. Here, we report a case of a 57-year-old man with end stage renal disease and complete central venous stenosis who presented with recurrent right-sided chylothorax. It was complicated with sepsis and multilocated empyema and treated successfully with intra-pleural fibrinolytic therapy using alteplase. Key Words: Chylothorax, empyema, intrapleural fibrinolysis Introduction effusions and empyema in the adult population for the outcomes of treatment failure (surgical Chyle is a non-inflammatory, bacteriostatic fluid intervention or death) and surgical intervention with a variable protein, fat and a lymphocyte alone (4). Our patient had chylothorax which was predominance of the total nucleated cells. (1,2) complicated with empyema and treated with Incidence data are available for only post- combination of intravenous antibiotic and operative chylothorax, which can occur after sequential intra-pleural alteplase (without almost any surgical operation in the chest. It is deoxyribonuclease) administered to different most often observed after esophagectomy (about pleural locules. 3% of cases), or after heart surgery in children (up to about 6% of cases) (1). -

Left Atheroma Mass and Occurrence Out-Of-Office Hypertension in an Extensive Population Raimondo Thomas*

Editorial iMedPub Journals Journal of Cardiovascular Medicine and Therapy 2021 www.imedpub.com Vol.4 No.1:e001 Left Atheroma Mass and Occurrence Out-of-Office Hypertension in an Extensive Population Raimondo Thomas* Department of Cardiology, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia *Corresponding author: Thomas R, Department of Cardiology, Alfaisal University, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia, E-mail: [email protected] Received date: February 01, 2021; Accepted date: February 15, 2021; Published date: February 22, 2021 Citation: Thomas R (2021) Left Atheroma Mass and Occurrence out- - of Office Hypertension in an Extensive Population. J Cardiovasc Med Ther Vol.4 No.1: e001 supplementation, physical activity, reduced alcohol consumption, and low-fat diets rich in fruits and vegetables have Abstract been effective in lowering BP and avert hypertension. Hypertension is an important risk factor for the development of cardiovascular disease, and is a major cause Discussion of morbidity and mortality worldwide. Traditionally, The current array of drug and nondrug therapeutic options hypertension diagnosis and treatment and clinical permit for control of hypertension to currently recommended evaluations of antihypertensive efficacy have been based on office blood pressure (BP) measurements; however, there is goal BP levels in all but the rarest patient and supply the increasing evidence that office measures may provide capacity to decrease BP to levels much lower than current inadequate or misleading estimates of a patient’s true BP guidelines recommend. Despite this capability, the vast majority status and level of cardiovascular risk. The introduction, and of patients with hypertension worldwide are untreated or badly endorsement by treatment guidelines, of 24-hour treated. -

Risk Factors in Abdominal Aortic Aneurysm and Aortoiliac Occlusive

OPEN Risk factors in abdominal aortic SUBJECT AREAS: aneurysm and aortoiliac occlusive PHYSICAL EXAMINATION RISK FACTORS disease and differences between them in AORTIC DISEASES LIFESTYLE MODIFICATION the Polish population Joanna Miko ajczyk-Stecyna1, Aleksandra Korcz1, Marcin Gabriel2, Katarzyna Pawlaczyk3, Received Grzegorz Oszkinis2 & Ryszard S omski1,4 1 November 2013 Accepted 1Institute of Human Genetics, Polish Academy of Sciences, Poznan, 60-479, Poland, 2Department of Vascular Surgery, Poznan 18 November 2013 University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, 61-848, Poland, 3Department of Hypertension, Internal Medicine, and Vascular Diseases, Poznan University of Medical Sciences, Poznan, 61-848, Poland, 4Department of Biochemistry and Biotechnology of the Poznan Published University of Life Sciences, Poznan, 60-632, Poland. 18 December 2013 Abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and aortoiliac occlusive disease (AIOD) are multifactorial vascular Correspondence and disorders caused by complex genetic and environmental factors. The purpose of this study was to define risk factors of AAA and AIOD in the Polish population and indicate differences between diseases. requests for materials should be addressed to J.M.-S. he total of 324 patients affected by AAA and 328 patients affected by AIOD was included. Previously (joannastecyna@wp. published population groups were treated as references. AAA and AIOD risk factors among the Polish pl) T population comprised: male gender, advanced age, myocardial infarction, diabetes type II and tobacco smoking. This study allowed defining risk factors of AAA and AIOD in the Polish population and could help to develop diagnosis and prevention. Characteristics of AAA and AIOD subjects carried out according to clinical data described studied disorders as separate diseases in spite of shearing common localization and some risk factors. -

Association Between Multi-Site Atherosclerotic Plaques and Systemic Arteriosclerosis

Association between multi-site atherosclerotic plaques and systemic arteriosclerosis: results from the BEST study (Beijing Vascular Disease Patients Evaluation Study) huan liu Peking University Shougang Hospital https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6223-7677 Jinbo Liu Peking University Shougang Hospital Wei Huang Peking University Shougang Hospital Hongwei Zhao Peking University Shougang Hospital Na zhao Peking University Shougang Hospital Hongyu wang ( [email protected] ) Research Keywords: arteriosclerosis, atherosclerosis, atherosclerotic plaque, carotid femoral artery pulse wave velocity CF-PWV Posted Date: June 8th, 2020 DOI: https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-31641/v1 License: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Read Full License Version of Record: A version of this preprint was published on August 1st, 2020. See the published version at https://doi.org/10.1186/s12947-020-00212-3. Page 1/18 Abstract Background Arteriosclerosis can be reected in various aspect of the artery, including atherosclerotic plaque formation or stiffening on the arterial wall. Both arteriosclerosis and atherosclerosis are important and closely associated with cardiovascular disease (CVD). The aim of the study was to evaluate the association between systemic arteriosclerosis and multi-site atherosclerotic plaques. Methods The study was designed as an observational cross-sectional study. A total of 1178 participants (mean age 67.4 years; 52.2% male) enrolled into the observational study from 2010 to 2017. Systemic arteriosclerosis was assessed by carotid femoral artery pulse wave velocity (CF-PWV) and multi-site atherosclerotic plaques (MAP, >=2 of the below sites) were reected in the carotid or subclavian artery, abdominal aorta and lower extremities arteries using ultrasound equipment.