Fortune Ku 0099D 16504 DAT

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument

Columbus State University CSU ePress Theses and Dissertations Student Publications 5-2016 The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument Victoria A. Hargrove Follow this and additional works at: https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations Part of the Music Commons Recommended Citation Hargrove, Victoria A., "The Evolution of the Clarinet and Its Effect on Compositions Written for the Instrument" (2016). Theses and Dissertations. 236. https://csuepress.columbusstate.edu/theses_dissertations/236 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Publications at CSU ePress. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of CSU ePress. THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT Victoria A. Hargrove COLUMBUS STATE UNIVERSITY THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT A THESIS SUBMITTED TO HONORS COLLEGE IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE HONORS IN THE DEGREE OF BACHELOR OF MUSIC SCHWOB SCHOOL OF MUSIC COLLEGE OF THE ARTS BY VICTORIA A. HARGROVE THE EVOLUTION OF THE CLARINET AND ITS EFFECT ON COMPOSITIONS WRITTEN FOR THE INSTRUMENT By Victoria A. Hargrove A Thesis Submitted to the HONORS COLLEGE In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for Honors in the Degree of BACHELOR OF MUSIC PERFORMANCE COLLEGE OF THE ARTS Thesis Advisor Date ^ It, Committee Member U/oCWV arcJc\jL uu? t Date Dr. Susan Tomkiewicz A Honors College Dean ABSTRACT The purpose of this lecture recital was to reflect upon the rapid mechanical progression of the clarinet, a fairly new instrument to the musical world and how these quick changes effected the way composers were writing music for the instrument. -

1 Making the Clarinet Sing

Making the Clarinet Sing: Enhancing Clarinet Tone, Breathing, and Phrase Nuance through Voice Pedagogy D.M.A Document Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alyssa Rose Powell, M.M. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2020 D.M.A. Document Committee Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Advisor Dr. Scott McCoy Dr. Eugenia Costa-Giomi Professor Katherine Borst Jones 1 Copyrighted by Alyssa Rose Powell 2020 2 Abstract The clarinet has been favorably compared to the human singing voice since its invention and continues to be sought after for its expressive, singing qualities. How is the clarinet like the human singing voice? What facets of singing do clarinetists strive to imitate? Can voice pedagogy inform clarinet playing to improve technique and artistry? This study begins with a brief historical investigation into the origins of modern voice technique, bel canto, and highlights the way it influenced the development of the clarinet. Bel canto set the standards for tone, expression, and pedagogy in classical western singing which was reflected in the clarinet tradition a hundred years later. Present day clarinetists still use bel canto principles, implying the potential relevance of other facets of modern voice pedagogy. Singing techniques for breathing, tone conceptualization, registration, and timbral nuance are explored along with their possible relevance to clarinet performance. The singer ‘in action’ is presented through an analysis of the phrasing used by Maria Callas in a portion of ‘Donde lieta’ from Puccini’s La Bohème. This demonstrates the influence of text on interpretation for singers. -

RCM Clarinet Syllabus / 2014 Edition

FHMPRT396_Clarinet_Syllabi_RCM Strings Syllabi 14-05-22 2:23 PM Page 3 Cla rinet SYLLABUS EDITION Message from the President The Royal Conservatory of Music was founded in 1886 with the idea that a single institution could bind the people of a nation together with the common thread of shared musical experience. More than a century later, we continue to build and expand on this vision. Today, The Royal Conservatory is recognized in communities across North America for outstanding service to students, teachers, and parents, as well as strict adherence to high academic standards through a variety of activities—teaching, examining, publishing, research, and community outreach. Our students and teachers benefit from a curriculum based on more than 125 years of commitment to the highest pedagogical objectives. The strength of the curriculum is reinforced by the distinguished College of Examiners—a group of fine musicians and teachers who have been carefully selected from across Canada, the United States, and abroad for their demonstrated skill and professionalism. A rigorous examiner apprenticeship program, combined with regular evaluation procedures, ensures consistency and an examination experience of the highest quality for candidates. As you pursue your studies or teach others, you become not only an important partner with The Royal Conservatory in the development of creativity, discipline, and goal- setting, but also an active participant, experiencing the transcendent qualities of music itself. In a society where our day-to-day lives can become rote and routine, the human need to find self-fulfillment and to engage in creative activity has never been more necessary. The Royal Conservatory will continue to be an active partner and supporter in your musical journey of self-expression and self-discovery. -

The Recently Rediscovered Works of Heinrich Baermann by Madelyn Moore Submitted to the Graduate Degree Program in Music And

The Recently Rediscovered Works of Heinrich Baermann By Madelyn Moore Submitted to the graduate degree program in Music and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Music. ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Eric Stomberg ________________________________ Dr. Robert Walzel ________________________________ Dr. Paul Popiel ________________________________ Dr. David Alan Street ________________________________ Dr. Marylee Southard Date Defended: April 1, 2014 The Dissertation Committee for Madelyn Moore certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: The Recently Rediscovered Works of Heinrich Baermann ________________________________ Chairperson Dr. Eric Stomberg Date approved: April 22, 2014 ii Abstract While Heinrich Baermann was one of the most famous virtuosi of the first half of the nineteenth century and is one of the most revered clarinetists of all time, it is not well known that Baermann often performed works of his own composition. He composed nearly 40 pieces of varied instrumentation, most of which, unfortunately, were either never published or are long out of print. Baermann’s style of playing has influenced virtually all clarinetists since his life, and his virtuosity inspired many composers. Indeed, Carl Maria von Weber wrote two concerti, a concertino, a set of theme and variations, and a quintet all for Baermann. This document explores Baermann’s relationships with Weber and other composers, and the influence that he had on performance practice. Furthermore, this paper discusses three of Baermann’s compositions, critical editions of which were made during the process of this research. The ultimate goal of this project is to expand our collective knowledge of Heinrich Baermann and the influence that he had on performance practice by examining his life and three of the works that he wrote for himself. -

David Dzubay

all water has a perfect memory DAVID DZUBAY david Dzubay Disc A 69:46 Disc B 58:29 String Quartet No. 1 “Astral” 1. Double Black Diamond 10:08 common sense COMPOSERS’ COLLECTIVE SPARK 1. Voyage 5:57 Indiana University New Music Ensemble; 2. Starry Night 4:07 David Dzubay, conductor 3. S.E.T.I. 1:50 4. Wintu Dream Song 6:23 Kukulkan II 5. Supernova 3:39 2. Kukulkan’s Ascent (El Castillo March equinox) 2:37 all water has a perfect memory Orion String Quartet 3. Water Run (Profane Well) 3:31 6. all water has a perfect memory 15:12 4. Celestial Determination (El Caracol) 1:56 Voices of Change 5. Processional-Offering (Sacred Well) 4:51 6. Quetzalcoatl’s Sacrifice (The Great Ball Court) 4:13 7. Producing For A While 8:21 7. Kukulkan’s Descent (El Castillo September equinox) 2:13 Voices of Change Indiana University New Music Ensemble 8. Delicious Silence 7:11 Chamber Concerto for Trumpet, Violin & Ensemble Miranda Cuckson, violin 8. Déjà vu (passacaglia sospeso) 13:20 9. Rapprochement (intermezzo) 9:08 9. Lament 9:28 10. Détente(s) (scherzo) 6:31 Barkada Quartet Indiana University New Music Ensemble; 10. Volando 4:27 David Dzubay, conductor Zephyr Simin Ganatra, violin John Rommel, trumpet/flugelhorn/piccolo trumpet 11. Lullaby 3:09 Emily Levin, harp innova 011 © David Dzubay. All Rights Reserved, 2019. innova 024 innova® Recordings is the label of the American Composers Forum. innova.mu pronovamusic.com all water has a perfect memory solo, chamber and ensemble music by David Dzubay Welcome to this survey of some of my music from the narrative-based music remains somewhat abstract and early 21st century! The first disc assembles performanc- personal; the composer and audience may have very es from a variety of chamber ensembles and soloists, different interpretations of the same music because so spanning a period from 2003-2015. -

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter

Beethoven, Bagels & Banter SUN / OCT 21 / 11:00 AM Michele Zukovsky Robert deMaine CLARINET CELLO Robert Davidovici Kevin Fitz-Gerald VIOLIN PIANO There will be no intermission. Please join us after the performance for refreshments and a conversation with the performers. PROGRAM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770-1827) Trio in B-flat major, Op. 11 I. Allegro con brio II. Adagio III. Tema: Pria ch’io l’impegno. Allegretto Olivier Messiaen (1908-1992) Quartet for the End of Time (1941) I. Liturgie de cristal (“Crystal liturgy”) II. Vocalise, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Vocalise, for the Angel who announces the end of time”) III. Abîme des oiseau (“Abyss of birds”) IV. Intermède (“Interlude”) V. Louange à l'Éternité de Jésus (“Praise to the eternity of Jesus”) VI. Danse de la fureur, pour les sept trompettes (“Dance of fury, for the seven trumpets”) VII. Fouillis d'arcs-en-ciel, pour l'Ange qui annonce la fin du Temps (“Tangle of rainbows, for the Angel who announces the end of time) VIII. Louange à l'Immortalité de Jésus (“Praise to the immortality of Jesus”) This series made possible by a generous gift from Barbara Herman. PERFORMANCES MAGAZINE 20 ABOUT THE ARTISTS MICHELE ZUKOVSKY, clarinet, is an also produced recordings of several the Australian National University. American clarinetist and longest live performances by Zukovsky, The Montréal La Presse said that, serving member of the Los Angeles including the aforementioned Williams “Robert Davidovici is a born violinist Philharmonic Orchestra, serving Clarinet Concerto. Alongside her in the most complete sense of from 1961 at the age of 18 until her busy performing schedule, Zukovsky the word.” In October 2013, he retirement on December 20, 2015. -

O Ensino Da Clarineta Em Nível Superior: Materiais Didáticos E O Desenvolvimento Técnico-Interpretativo Do Clarinetista

Universidade Federal da Paraíba Centro de Comunicação, Turismo e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música Mestrado em Música O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista Eduardo Filippe de Lima João Pessoa Março de 2019 Universidade Federal da Paraíba Centro de Comunicação, Turismo e Artes Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música Mestrado em Música O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista Eduardo Filippe de Lima Orientador: Dr. Fábio Henrique Gomes Ribeiro Trabalho apresentado ao Programa de Pós-Graduação em Música da Universidade Federal da Paraíba como requisito para a obtenção do título de Mestre em Música, área de concentração em Educação Musical. João Pessoa Março de 2019 Catalogação na publicação Seção de Catalogação e Classificação L732e Lima, Eduardo Filippe de. O Ensino da Clarineta em Nível Superior: materiais didáticos e o desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinetista / Eduardo Filippe de Lima. - João Pessoa, 2019. 111f. : il. Orientação: Fábio Henrique Gomes Ribeiro. Dissertação (Mestrado) - UFPB/CCTA. 1. Ensino de instrumento musical. 2. Ensino da clarineta em nível superior. 3. Materiais didáticos para clarineta. 4. Desenvolvimento técnico-interpretativo do clarinet. I. Ribeiro, Fábio Henrique Gomes. II. Título. UFPB/BC 3 AGRADECIMENTOS Gostaria de agradecer imensamente a todos que contribuíram de maneira direta e indireta para a conclusão desse curso de mestrado, o qual me trouxe um profundo amadurecimento pessoal e profissional, e que simboliza o encerramento de mais um ciclo na minha carreira musical. À minha família, que sempre me deu apoio e o suporte necessário para continuar com todos os meus projetos, incluindo esse curso; Ao meu orientador, prof. -

The Clarinet World

REVIEWS AUDIO NOTES by Kip Franklin Milton Babbit’s Composition for Four undauntedly masters the rapidly cascading Instruments begins with an extended arpeggios in the scherzando section and Stanley Drucker is unquestionably a titan clarinet passage that Drucker performs conveys control and color in the more of the clarinet world. In addition to his six in an improvisational off-the-cuff lyrical passages. This orchestration is decades with the New York Philharmonic manner. The work features a variety of a refreshing departure from the more (nearly five of them as principal clarinet), instrumental timbres and techniques, traditional clarinet and piano version. his career entails many commissions and resulting in a unique tapestry that Like Nature Moods and Contrasts, recordings. A new double-disc set, Stanley resembles the pointillistic writings of Weigl’s New England Suite showcases Drucker: Heritage Collection 6-7, Webern and Boulez. Valley Weigl’s Nature Drucker’s aptitude as a chamber musician. contains recordings of Drucker playing Moods ensues, with Drucker showcasing Her writing allows each instrument solo many of the most colossal works in the his ability to emulate the human voice. passages while still creating interwoven repertoire, as well as many important and Each of the five movements in this work and complex ensemble textures. Drucker’s rarely-played or obscure smaller works conveys a bucolic ambience with perfectly mellow, deep tone makes this an spanning the entirety of his career. That interwoven counterpoint between the especially memorable piece; at times it Drucker is on display as both a soloist clarinet, voice and violin. The balance in is contemplative and ponderous, and at and chamber musician throughout this this particular work is exceptional, with others jubilant and capricious. -

Courtesy of Eric Nelson, As Posted on Klarinet, 9 and 11 Feb 1997. Eric Nelson Is Clarinetist with the Lightwood Duo, an Actively Touring Clarinet/Guitar Duo

Courtesy of Eric Nelson, as posted on Klarinet, 9 and 11 Feb 1997. Eric Nelson is clarinetist with The Lightwood Duo, an actively touring clarinet/guitar duo. Their CDs are available through their website, http://www.lightwoodduo.com. About two weeks ago, there were some questions about Aage Oxenvad on the list. Having studied Nielsen and clarinet at the Royal Conservatory in Copenhagen [in 1979], I would like to pass on some first-hand information on Oxenvad. There are two major obstacles to acquiring accurate information about Danish music. First, much of the info exists only in the Danish language; not exactly a familiar language to most. Second, the Danes are not inclined to value the sharing of such information. To quote Tage Scharff, the clarinet professor with whom I studied: "You Americans [and English as well] love to get together and give lectures, deliver papers, and hold conferences. Here in Denmark, vi spiller! [we PLAY]". He was quite amused that I, a performing clarinetist, would be so interested in such material. On a posting on this list, Jarle Brosveet wrote: "In the first place Oxenvad did not inspire Nielsen to write the concerto, although he was the first to perform it. It was written at the request of Nielsen's benefactor and one-time student Carl Johan Michaelsen. Second, Oxenvad, who is described as a choleric, made this unflattering remark about Nielsen and the concerto: "He must be able to play the clarinet himself, otherwise the would hardly have been able to find the worst notes to play." Oxenvad performed it on several occasions with no apparent success although he reportedly did all he could, whatever that is supposed to mean. -

Proposal to Create the Doctor of Musical Arts Degree Program

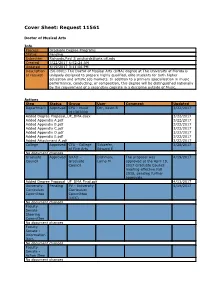

Cover Sheet: Request 11561 Doctor of Musical Arts Info Process Graduate Degree Programs Status Pending Submitter Richards,Paul S [email protected] Created 3/22/2017 6:52:24 AM Updated 4/19/2017 3:11:06 PM Description (50.0901) The Doctor of Musical Arts (DMA) degree at The University of Florida is of request uniquely designed to prepare highly qualified, elite students for both higher education and artistic job markets. In addition to a primary specialization in music performance, conducting, or composition, this degree will be distinguished nationally by the requirement of a secondary cognate in a discipline outside of Music. Actions Step Status Group User Comment Updated Department Approved CFA - Music Orr, Kevin R 3/22/2017 011303000 Added Degree Proposal_UF_DMA.docx 3/22/2017 Added Appendix A.pdf 3/22/2017 Added Appendix B.pdf 3/22/2017 Added Appendix C.pdf 3/22/2017 Added Appendix D.pdf 3/22/2017 Added Appendix E.pdf 3/22/2017 Added Attachment A.pdf 3/22/2017 College Approved CFA - College Schaefer, 3/28/2017 of Fine Arts Edward E No document changes Graduate Approved GRAD - Dishman, The proposal was 4/19/2017 Council Graduate Lorna M approved at the April 19, Council 2017 Graduate Council meeting effective Fall 2018, pending further approvals. Added Degree Proposal_UF_DMA Final.pdf 4/13/2017 University Pending PV - University 4/19/2017 Curriculum Curriculum Committee Committee (UCC) No document changes Faculty Senate Steering Committee No document changes Faculty Senate - Information Item No document changes Faculty Senate - -

A Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in This Issue

Vol. 45 • No. 1 December 2017 Tao AChunxiao: Chinese Clarinet Legend Also in this issue... ClarinetFest® 2017 Report The Genesis of Gustav Jenner’s Clarinet Sonata D’ADDARIO GIVES ME THE FREEDOM TO PRODUCE THE SOUND I HEAR IN MY HEAD. — JONATHAN GUNN REINVENTING CRAFTSMANSHIP FOR THE 21ST CENTURY. President’sThe EDITOR Rachel Yoder [email protected] ASSOCIATE EDITOR Jessica Harrie [email protected] EDITORIAL BOARD Dear ICA Members, Mitchell Estrin, Heike Fricke, Jessica Harrie, ope you are enjoying a wonderful new season Caroline Hartig, Rachel Yoder of music making with fulflling activities and MUSIC REVIEWS EDITOR events. Many exciting things are happening in Gregory Barrett – [email protected] our organization. Te ICA believes that if you Hdo good things, good things happen! I want to thank everyone AUDIO REVIEWS EDITOR who has contributed to our Capital Campaign. We especially Chris Nichols – [email protected] wish to thank Alan and Janette Stanek for their amazing gift of $11,250.00 to fund our competitions for the coming GRAPHIC DESIGN ClarinetFest® 2018. Te ICA is grateful for your generosity Karry Tomas Graphic Design and the generosity of all Capital Campaign donors. Please [email protected] visit www.youcaring.com/internationalclarinetassociation to Caroline Hartig make your donation today. We would love to hear your story ADVERTISING COORDINATOR and look forward to our continued campaign which will last Elizabeth Crawford – [email protected] through ClarinetFest® 2018. Also, visit www.clarinet.org/ donor-wall to check out our donor wall with many photos and thank-yous to those who INDEX MANAGER contributed to the ICA for ClarinetFest® 2017. -

A Survey of Discrepancies Among Solo Parts of Editions and Manuscripts of Carl Maria Von Weber's Concerto No

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1991 A Survey of Discrepancies Among Solo Parts of Editions and Manuscripts of Carl Maria Von Weber's Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 73. Ronnie Everett rW ay Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Wray, Ronnie Everett, "A Survey of Discrepancies Among Solo Parts of Editions and Manuscripts of Carl Maria Von Weber's Concerto No. 1 in F Minor, Op. 73." (1991). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 5285. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/5285 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion.