HEALTHY PARKS, SCHOOLS and COMMUNITIES: Mapping Green Access and Equity for Southern California

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Campground East of Highway

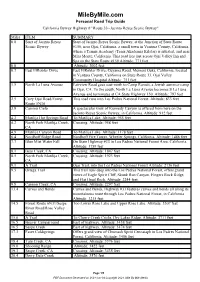

MileByMile.com Personal Road Trip Guide California Byway Highway # "Route 33--Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway" Miles ITEM SUMMARY 0.0 Start of Jacinto Reyes Start of Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway, at the Junction of State Route Scenic Byway #150, near Ojai, California, a small town in Ventura County, California, where a Tennis Academy (Tenis Akademia Kilatas) is situated, and near Mira Monte, California. This road lies just across Ojai Valley Inn and Spa on the State Route #150 Altitude: 771 feet 0.0 Altitude: 3002 feet 0.7 East ElRoblar Drive East ElRoblar Drive, Cuyama Road, Meiners Oaks, California, located in Ventura County, California on State Route 33, Ojai Valley Community Hospital Altitude: 751 feet 1.5 North La Luna Avenue Fairview Road goes east-north to Camp Ramah, a Jewish summer camp in Ojai, CA. To the south, North La Luna Avenue becomes S La Luna Avenue and terminates at CA State Highway 150. Altitude: 797 feet 2.5 Cozy Ojai Road/Forest This road runs into Los Padres National Forest. Altitude: 833 feet Route 5N34 3.9 Camino Cielo A spectacular view of Kennedy Canyon is offered from here on the Jacinto Reyes Scenic Byway, in California. Altitude: 912 feet 4.2 Matilija Hot Springs Road To Matilija Lake. Altitude: 955 feet 4.2 North Fork Matilija Creek, Crossing. Altitude: 958 feet CA 4.9 Matilija Canyon Road To Matilija Lake. Altitude: 1178 feet 6.4 Nordhoff Ridge Road Nordhoff Fire Tower, Wheeler Springs, California. Altitude: 1486 feet 7.7 Blue Mist Water Fall On State Highway #33 in Los Padres National Forest Area, California. -

Table of Contents

4.4 Recreation 1 4.4 RECREATION 2 This section addresses a variety of offshore and onshore recreational activities that 3 could be impacted by the Proposed Project. Recreational facilities and activities in the 4 region are described in Section 4.4.1. The impacts of the Proposed Project on 5 recreational activities are evaluated, and the need for mitigation is discussed in Section 6 4.4.4. Alternatives to the Proposed Project are analyzed in Section 4.4.5. 7 4.4.1 Description of Resource/Environmental Setting 8 Southern California residents derive enjoyment from active and passive recreational use 9 of the natural and semi-natural areas in the coastal environment. The mild climate and 10 the attractions of the ocean and environs draw many people to the coast in the vicinity 11 of the Proposed Project. 12 Generally, the land uses along the coastline are public beaches, marinas, and/or 13 harbors. MCB Camp Pendleton has 18 miles (29 km) of coastline and prohibits public 14 access to the beach. Inland from the immediate coastline, the land use pattern is 15 typically mixed with residential and supporting commercial uses (City of San Clemente 16 1992a). 17 Recreation Facilities 18 A wide variety of public facilities are available for recreation in the vicinity of the 19 Proposed Project. Those nearest to the shore have the potential to be affected by the 20 proposed activities (Figure 4.4-1). A list of public parks and their proximity to the project 21 site is provided in Table 4.4-1. -

Chamber Addresses Jobs and the Economy at L.A. City Hall Standing

Chamber VOICE IN THIS ISSUE: 10 ways the Chamber helped L.A. business this quarter 3 Chamber Southern California Leadership Network grooms leaders 4 Chamber forms new Non Profit Council 6 FALL 2007 • VolumE 6 • issue 4 VOICE A quarterly publication of the Los Angeles Area Chamber of Commerce Chamber addresses jobs and the economy at L.A. Standing with the City Hall Governor on health care reform The Chamber advocated for issues important to the City of Los Angeles at annual Access L.A. City Hall event he Los early 400 business leaders Garcetti echoed the need for more Angeles gathered for the Los collaboration, mentioning his efforts to Area Angeles Area Chamber make the council more aware of business Chamber of of Commerce’s annual issues through the creation of the Jobs, Commerce Access L.A. City Hall event Business Growth and Tax Reform endorsed Gov. committee. Chick suggested Arnold Schwarzenegger’s the need for a citywide health care reform economic development proposal in September, making it one of the first policy that would help business organizations to businesses grow and plan for come out in support of their future. the plan. Throughout the morning, The proposal includes a Chamber members heard 4 percent payroll fee on REFORMING HEALTH CARE. Chamber Board Chair David Fleming, Latham & Watkins, LLP, and Chamber President & CEO Gary Toebben discuss health care from more than 30 civic employers with 10 or with Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger after a Capitol News Conference on Sept. 17. leaders and lawmakers on more employees who do key issues in Los Angeles. -

U.S. Mayors to Meet with President Barack Obama at the White House on Friday, February 20, 2009

For Immediate Release: Contact: Elena Temple Wednesday, February 19, 2009 202-309-4906 ([email protected]) Carlos Vogel 202-257-9797 ([email protected]) U.S. MAYORS TO MEET WITH PRESIDENT BARACK OBAMA AT THE WHITE HOUSE ON FRIDAY, FEBRUARY 20, 2009 Washington, D.C. – The nation’s mayors have been invited by U.S. President Barack Obama and U.S. Vice President Joseph Biden to the White House for a meeting with The Conference of Mayors leadership on the morning of Friday, February 20, 2009. Led by U.S. Conference of Mayors President Miami Mayor Manny Diaz, over 60 mayors will also meet with Attorney General Eric H. Holder, Jr., Housing and Urban Development Secretary Shaun Donovan, Transportation Secretary Ray LaHood, Energy Secretary Dr. Steven Chu, Education Secretary Arne Duncan and White House Senior Staff. The mayors meeting with President Obama and Vice President Biden will take place from 10:30 a.m. to 11:15 a.m. in the East Room of the White House and will be OPEN to the press. The mayors will also hold a press availability at the White House at 11:30 a.m. immediately following the meeting (location is TBD). Following the White House meeting, the mayors will gather at the Capitol Hilton in Washington, D.C. for a session with U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Administrator Lisa Jackson, U.S. Department of Energy Weatherization Program Director Gil Sperling, and U.S. Department of Justice COPS Office Acting Director Tim Quinn. This meeting is CLOSED to the press. The nation’s mayors commend President Obama and Congress for the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act, which is in line with the U.S. -

UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes Among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Santa Barbara Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by Kristina Marie Gill Committee in charge: Professor Michael A. Glassow, Chair Professor Michael A. Jochim Professor Amber M. VanDerwarker Professor Lynn H. Gamble September 2015 The dissertation of Kristina Marie Gill is approved. __________________________________________ Michael A. Jochim __________________________________________ Amber M. VanDerwarker __________________________________________ Lynn H. Gamble __________________________________________ Michael A. Glassow, Committee Chair July 2015 Ancient Plant Use and the Importance of Geophytes among the Island Chumash of Santa Cruz Island, California Copyright © 2015 By Kristina Marie Gill iii DEDICATION This dissertation is dedicated to my Family, Mike Glassow, and the Chumash People. iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people who have provided guidance, encouragement, and support in my career as an archaeologist, and especially through my undergraduate and graduate studies. For those of whom I am unable to personally thank here, know that I deeply appreciate your support. First and foremost, I want to thank my chair Michael Glassow for his patience, enthusiasm, and encouragement during all aspects of this daunting project. I am also truly grateful to have had the opportunity to know, learn from, and work with my other committee members, Mike Jochim, Amber VanDerwarker, and Lynn Gamble. I cherish my various field experiences with them all on the Channel Islands and especially in southern Germany with Mike Jochim, whose worldly perspective I value deeply. I also thank Terry Jones, who provided me many undergraduate opportunities in California archaeology and encouraged me to attend a field school on San Clemente Island with Mark Raab and Andy Yatsko, an experience that left me captivated with the islands and their history. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

12Th Grade Curriculum

THE TOM BRADLEY PROJECT STANDARDS: 12.6.6 Evaluate the rolls of polls, campaign advertising, and controversies over campaign funding. 12.6.6 Analyze trends in voter turnout. COMMON CORE STATE KEY TERMS AND ESSAY QUESTION STANDARDS CONTENT Reading Standards for Literacy in elections History/Social Studies 6-12 How did the election of Tom shared power Bradley in 1973 reflect the local responsibilities and Writing Standard for Literacy in building of racial coalitions in authority History/Social Studies 6-12 voting patterns in the 1970s and Text Types and Purpose the advancement of minority 2. Write informative/explanatory texts, opportunities? including the narration of historical events, scientific procedures/experiments, or technical processes. B. Develop the topic with relevant, well-chosen facts, definitions, concrete details, quotations, or other information and expamples LESSON OVERVIEW MATERIALS Doc. A LA Times on Voter turnout, May 15, 2003 Day 1 View Module 2 of Tom Bradley video. Doc. B Voter turnout spreadsheet May 15, 2003 (edited) Read Tom Bradley biography. Doc. C Statistics May 15,2003 Day 2 Doc. D Tom Bradley biography Analyze issues related to voter turnout in Doc. E Census, 2000 2013 Los Angeles Mayoral Election and Doc, F1973 Mayoral election connections to the 1973 campaign for Doc .G Interview 1973 Mayor. Doc. H Election Night speech 1989 Day 3 Doc I LA Times Bradley’s first year 1974 Analyze issues in 1973 campaign. Doc. J LA Times Campaign issues 1973 Analyze building of racial coalitions Doc K LA Times articles 1973 among voters. Day 4 Doc. L LA Times campaign issues 1973 Write essay. -

Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo

PACIFYING PARADISE: VIOLENCE AND VIGILANTISM IN SAN LUIS OBISPO A Thesis presented to the Faculty of California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in History by Joseph Hall-Patton June 2016 ii © 2016 Joseph Hall-Patton ALL RIGHTS RESERVED iii COMMITTEE MEMBERSHIP TITLE: Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo AUTHOR: Joseph Hall-Patton DATE SUBMITTED: June 2016 COMMITTEE CHAIR: James Tejani, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Murphy, Ph.D. Associate Professor of History COMMITTEE MEMBER: Kathleen Cairns, Ph.D. Lecturer of History iv ABSTRACT Pacifying Paradise: Violence and Vigilantism in San Luis Obispo Joseph Hall-Patton San Luis Obispo, California was a violent place in the 1850s with numerous murders and lynchings in staggering proportions. This thesis studies the rise of violence in SLO, its causation, and effects. The vigilance committee of 1858 represents the culmination of the violence that came from sweeping changes in the region, stemming from its earliest conquest by the Spanish. The mounting violence built upon itself as extensive changes took place. These changes include the conquest of California, from the Spanish mission period, Mexican and Alvarado revolutions, Mexican-American War, and the Gold Rush. The history of the county is explored until 1863 to garner an understanding of the borderlands violence therein. v TABLE OF CONTENTS Page CHAPTER INTRODUCTION…………………………………………………………... 1 PART I - CAUSATION…………………………………………………… 12 HISTORIOGRAPHY……………………………………………........ 12 BEFORE CONQUEST………………………………………..…….. 21 WAR……………………………………………………………..……. 36 GOLD RUSH……………………………………………………..….. 42 LACK OF LAW…………………………………………………….…. 45 RACIAL DISTRUST………………………………………………..... 50 OUTSIDE INFLUENCE………………………………………………58 LOCAL CRIME………………………………………………………..67 CONCLUSION………………………………………………………. -

Archdiocese of Los Angeles Catholic Directory 2020-2021

ARCHDIOCESE OF LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY 2020-2021 Mission Basilica San Buenaventura, Ventura See inside front cover 01-FRONT_COVER.indd 1 9/16/2020 3:47:17 PM Los Angeles Archdiocesan Catholic Directory Archdiocese of Los Angeles 3424 Wilshire Boulevard Los Angeles, CA 90010-2241 2020-21 Order your copies of the new 2020-2021 Archdiocese of Los Angeles Catholic Directory. The print edition of the award-winning Directory celebrates Mission San Buenaventura named by Pope Francis as the first basilica in the Archdiocese. This spiral-bound, 272-page Directory includes Sept. 1, 2020 assignments – along with photos of the new priests and deacons serving the largest Archdiocese in the United States! The price of the 2020-21 edition is $30.00 (shipping included). Please return your order with payment to assure processing. (As always, advertisers receive one complimentary copy, so consider advertising in next year’s edition.) Directories are scheduled to begin being mailed in October. _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Please return this portion with your payment REG Archdiocese of Los Angeles 2020-2021 LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY ORDER FORM YES, send the print version of the 2020-21 ARCHDIOCESE OF LOS ANGELES CATHOLIC DIRECTORY at the flat rate of $30.00 each. Please return your order with payment to assure processing. -

Native Sustainment: the North Fork Mono Tribe's

Native Sustainment The North Fork Mono Tribe's Stories, History, and Teaching of Its Land and Water Tenure in 1918 and 2009 Jared Dahl Aldern Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy from Prescott College in Education with a Concentration in Sustainability Education May 2010 Steven J. Crum, Ph.D. George Lipsitz, Ph.D. Committee Member Committee Member Margaret Field, Ph.D. Theresa Gregor, Ph.D. External Expert Reader External Expert Reader Pramod Parajuli, Ph.D. Committee Chair Native Sustainment ii Copyright © 2010 by Jared Dahl Aldern. All rights reserved. No part of this dissertation may be used, reproduced, stored, recorded, or transmitted in any form or manner whatsoever without written permission from the copyright holder or his agent(s), except in the case of brief quotations embodied in the papers of students, and in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles and reviews. Requests for such permission should be addressed to: Jared Dahl Aldern 2658 East Alluvial Avenue, #103 Clovis, CA 93611 Native Sustainment iii Acknowledgments Gratitude to: The North Fork Mono Tribe, its Chairman, Ron Goode, and members Melvin Carmen (R.I.P.), Lois Conner, Stan Dandy, Richard Lavelle, Ruby Pomona, and Grace Tex for their support, kindnesses, and teachings. My doctoral committee: Steven J. Crum, Margaret Field, Theresa Gregor, George Lipsitz, and Pramod Parajuli for listening, for reading, and for their mentorship. Jagannath Adhikari, Kat Anderson, Steve Archer, Donna Begay, Lisa -

Adopt-A-Beach Packet Final

The Adopt-A-Beach Program The Adopt-A-Beach Program is a statewide educational program coordinated by the California Coastal Commission. In San Diego County, this program is locally managed by I Love A Clean San Diego (ILACSD). To “adopt” a beach, volunteers agree to clean their beach at least three times over one year (school groups need only to commit to one cleanup). This program provides a unique opportunity for volunteers of all ages to be part of the solution to marine pollution. It’s as easy as 1, 2, 3… Check out the attached list of local beaches you can adopt. ILACSD will help you determine days and times for your cleanups, provide you with supplies and help arrange for trash and recycling pick-up. Recruit friends, co-workers, classmates and rela- tives to get involved in your beach cleanup. The more people you have cleaning, the more debris you can remove from the beach, saving animals from becoming entangled or injured. Clean your beach! Wear comfortable clothes that you don’t mind getting dirty, a hat, sunscreen and closed-toe shoes. Pick up trash & recyclables (e.g. bottles, cans, clean paper). And most importantly, have fun! The Adopt-A-Beach Program By adopting a beach, you will... Reduce ocean pollution Protect marine life Have fun & make a difference Want to learn more? I Love A Clean San Diego offers free presentations to groups adopting a beach. If your group is interested in learning more about your impact on the marine environment, please contact the ILACSD Volunteer Coordinator at (619) 291-0103 ext. -

IMPORTANT DATES: Mission Santa Barbara Structure and Legacy 1542 Santa Barbara Channel Is Discovered by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo

The Indians of IMPORTANT DATES: Mission Santa Barbara Structure and Legacy 1542 Santa Barbara Channel is discovered by Juan Rodríguez Cabrillo. The Indians residing in the Santa Barbara ARCHITECTURE: 1602 Sebastián Vizcaíno named the new area were Chumash, or Canalino. They were a hunting, fishing, and gathering In laying out the design of the church, Father Antonio Ripoll channel--- Canal de Santa Barbara. society. Between the years of 1786-1846, consulted at length and drew freely from Vetruvius‘ book on 1769 Portola Expedition camped in Santa Barbara en 4,715 Chumash Indians became architecture, written in the time of Caesar Augustus, about 25 B.C. What you witness today in this building is 2000 years of route to Monterey. Spain ruled over California Christians. Many are buried in the Mission cemetery. architectural design beginning in Greece, taken over by Rome, until 1821. passed along to Spain, and ending up in California. The facade of the Mission church was also taken from this classic work. The 1782 El Presidio of Santa Bárbara was founded by AGRICULTURE AND WATER SYSTEMS: architectural manual was translated from Latin into Spanish and Governor Felipe de Neve. Saint Junípero Serra is preserved in the historic Mission Archive Library to this day. The architectural style of the Mission combines elements of raised the cross. The Franciscans introduced Agriculture to the Chumash, primarily growing wheat, barley, corn, Greek, Roman, Spanish, moorish, and native influences. The result 1786 Mission Santa Barbara Founded by Fr. Fermín beans, and peas. Livestock at the Mission consisted of cattle, is a testimony to the blending of the imaginative abilities of the Spaniards and the advanced skills of the Chumash.