14370 Acadiensis Cover

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Modernism on the 'Margin' – the 'Margin' on Modernism

MTA Doktora Pályázat (dc_1044_15) Modernism on the 'Margin' – The 'Margin' on Modernism. Manifestations in Canadian Culture Válasz az opponensi véleményekre Mindenek előtt köszönettel tartozom opponenseimnek, hogy vállalták dolgozatom értékelését, bár más tudományterületre, illetve más kultúrába kellett átlépniük, mint talán szűkebben vett kutatási területük. Köszönöm Oliver Botar elismerő szavait az elméleti és történelmi háttér kidolgozására vonatkozóan. A kanadai professzor ugyanakkor nem rejti véka alá hiányérzeteit: megjegyzi, hogy a 'faji', 'etnicitásbeli', illetve a 'társadalmi nem'-et érintő szempontok egyenetlen mértékben érvényesülnek az elemzések során – ez részemről tudatos döntés volt, amint azt a Bevezetés utolsó bekezdésében (12.o.) kifejtettem, egyrészt amiatt, hogy ezek önálló szakterületek a tudományágon belül (Jewish Studies, Gender Studies, Etnic/Minority/Indigenous Studies), ily módon létezik szakirodalom ezeket részleteiben bemutatva, másrészt az érvelés koherenciája sérült volna beemelésükkel. Emily Carr-ral több tanulmány is foglalkozik az őslakos művészet és a nem-őslakos művész problematikájával összefüggésben (pl. Charles C. Hill az 1927-es National Gallery-ben rendezett kiállítást elemezve az Emily Carr. New Perspectives on a Canadian Icon című kötetben), ennek okából már nem kívántam kitérni erre az aspektusra. Lévén, hogy szakterületem az összehasonlító irodalomtudomány, nem érzem magam megfelelően kompetensnek képzőművészeti életművek értékelését illetően, mint amilyen a torontói Francis Loring és Florence -

Proquest Dissertations

UNIVERSITY OF CALGARY Prize Possession: Literary Awards, the GGs, and the CanLit Nation by Owen Percy A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF ENGLISH CALGARY, ALBERTA JANUARY 2010 ©OwenPercy 2010 Library and Archives Bibliotheque et 1*1 Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington OttawaONK1A0N4 OttawaONK1A0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre inference ISBN: 978-0-494-64130-9 Our file Notre r6f6rence ISBN: 978-0-494-64130-9 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library and permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par Nnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet, distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans le loan, distribute and sell theses monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, sur worldwide, for commercial or non support microforme, papier, electronique et/ou commercial purposes, in microform, autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in this et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. Ni thesis. Neither the thesis nor la these ni des extraits substantiels de celle-ci substantial extracts from it may be ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement printed or otherwise reproduced reproduits sans son autorisation. -

2 BC BOOKWORLD SPRING 2011 Awards STANDING up for SCIENCE

2 BC BOOKWORLD SPRING 2011 awards STANDING UP FOR SCIENCE eligion won’t save us. Or politics. R Or business. According to David Suzuki, the 74-year-old environmentalist who re- ceived the 18th annual George Wood- cock Lifetime Achievement Award in February, it all comes down to science. If politicians had listened to Suzuki and other scientific-minded futurists about thirty years ago, Kyoto Protocol standards would have been achievable. Now Suzuki still clings to a “very slen- der thread” of hope. The human race can still endure, IF we immediately en- act rational strategies. “Science is by far the most important factor for shaping our lives and society today… (but) decisions are made for po- litical expediency,” he says. “What’s hap- pening now is absolutely terrifying.” Suzuki recalled the advice of 300 cli- matologists who met in Toronto in the 1970s and identified global warming as the greatest threat to human survival, next to atomic bombs. “(But) the fossil fuel industry, the auto sector and neo- conservatives like the Koch brothers in Margaret Atwood New York began to invest tens of mil- presents this year’s George lions of dollars in a campaign of decep- Woodcock Award to tion,” Suzuki said. “You can find the best scientist and educator evidence of this in Jim Hoggan’s book, David Suzuki, at the Fairmont Climate Cover-Up, and in Nancy Hotel Vancouver. “We are Oreskes’ Merchants of Doubt.” going backwords,” he PHOTOGRAPHY D “Now we have public opinion on warned the audience. these issues driven by organizations like WENDY The Fraser Institute, the Heartland In- stitute, the Competitive Enterprise In- Campbell with a set of leather bound stitute. -

Download Download

The Governor General’s Literary Awards: English-Language Winners, 1936–2013 Andrew David Irvine* Entries are now being received for the Governor-General’s Annual Literary Awards for 1937, arranged by the Canadian Author’s Association. Medals will be given for the best books of fiction, poetry and general literature, respectively. The book must have been published during the calendar year 1937; and the author must be a Canadian. … There is no particular closing date. When the judges have read all the books, they will name the winners and that will end the matter. William Arthur Deacon1 This list2 of Governor General’s Literary Award–winning books differs from previous lists in several ways. It includes • five award-winning books from 1948, 1963, 1965, and 1984 (three in English and two in French) inadvertently omitted from previous lists; • the division of winning titles into historically accurate award categories; • a full list of books by non-winning finalists who have received cash prizes, a practice that began in 2002; • a full list of declined awards; • more detailed bibliographical information than can be found in most other lists; and 1* Andrew Irvine holds the position of professor and head of Economics, Philosophy, and Political Science at the University of British Columbia, Okanagan. Errata may be sent to the author at [email protected]. 11 William Arthur Deacon, The Fly Leaf, Globe and Mail, 9 April 1938, 15. 12 The list is split between two articles. The current article contains bibliographical information about English-language books that have won Governor General’s Literary Awards between 1936 and 2013. -

Unit-1 Canadian Poetry

UNIT-1 CANADIAN POETRY Structure 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Pre-Confederation Period 1.2.1 The First Stirrings of the Poetic Culture 1.3 Confederation Period 1.3.1 Emergence of a National Literature 1.4 Modernist Period: 1.4.1 First Phase 1.4.2 Second Phase 1.4.3 Third Phase 1.5 Postmodernist /Contemporary Period 1.6 Let Us Sum Up 1.7 Review Questions 1.8 Bibliography 1.0 Objectives · To introduce the students to an understanding of the phases of Canadian poetic culture; · To familiarize them with the representative poets of the different periods; · To help them understand Canadian response towards nature. · To enable the students to gain a knowledge of Canadian spirit in poetry. 1.1 Introduction Canadian poetry over the last two centuries divides roughly in four main periods : the pre- Confederation period, the Confederation period, the modernist period and the postmodernist period. Each period has the same integrity, the same skilful moderation that is aware of the continuity of its heritage and a recalcitrance of personality. This division of Canadian poetry does not mean the water- tight compartmentalization, rather, it is a continuous growth of Canadian poetry contributing to the cumulative identity that is Canadian. Canadian poetic culture is a growth having its first stirrings of poetics culture, emergence of a national poetic culture, transitional poetic culture, modernist poetic culture and post modernist or contemporary poetic culture. 1 1.2 Pre-Confederation Period The pre-Confederation period had the first stirrings of a poetic culture before Canada became a nation. -

Beyond the 49Th Parallel: Many Faces of the Canadian North Au-Dela Du

: Beyond the 49th Parallel: Parallel th Many Faces of the Canadian North Au-dela du 49eme parallele : multiples visages du Nord canadien Beyond the 49 Many Faces of the Canadian North Many Faces of the Canadian North Edited by / Edité par Évaine Le Calvé-Ivičević + Vanja Polić : parallele eme Au-dela du 49 multiples visages du Nord canadien zagreb_2019cover.indd 1 24.1.2019 14:25:20 Beyond the 49th Parallel: Many Faces of the Canadian North Au-dela du 49eme parallele : multiples visages du Nord canadien Edited by / Edité par Évaine Le Calvé-Ivičević + Vanja Polić Central European Association for Canadian Studies Association d’Etudes Canadiennes en Europe Centrale Masaryk University / Université Masaryk Brno 2018 zagreb_2019_text.indd 1 19.2.2019 11:07:07 Beyond the 49th Parallel: Many Faces of the Canadian North Au-delà du 49ème parallèle : multiples visages du Nord canadien Editors / Éditrices : Évaine Le Calvé-Ivičević (Université de Zagreb) Vanja Polić (University of Zagreb) Technical Editor/Rédacteur technique : Pavel Křepela (Czech Republic/République tchèque) Cover&typo/Maquette de la couverture et mise en page : Pavel Křepela (Czech Republic/République tchèque) Contact/Contact : www.cecanstud.cz [email protected] 1st edition, 2018. Circulation 100 copies / 1ère édition, 2018. Tirage 100 exemplaires Published by/Publié par Masaryk University, Brno 2018 Printed by/Imprimé par Ctrl P s.r.o., Bezručova 17a, 602 00 Brno Copyright © 2018 Central European Association for Canadian Studies Copyright © 2018 Masarykova univerzita ISBN 978-80-210-9192-4 (paperback) ISBN 978-80-210-9193-1 (online : pdf) zagreb_2019_text.indd 2 19.2.2019 11:07:07 content — table des matières Introduction / Introduction Évaine Le Calvé-Ivičević and / et Vanja Polić ............................................................................. -

Chronological Table

Chronological table Abbreviations: (D) = drama, (P) = prose, (V) = verse DATE AUTHOR AND TITLE EVENT 13000 BC Niagara Falls forms as glaciers retreat 11000 Earliest records of the Bluefish Cave people (Yukon) 10000 Receding of the last ice sheet 9000 Earliest records of the Fluted Point people (Ontario) 7000 Earliest records of human habitation on the West Coast of Canada Nomadic 'Archaic Boreal' Indian culture moves in to Arctic mainland 3000 Indian habitation in the Maritimes 0800 Dorset culture develops around Hudson Strait 0300 AD Village tradition established on prames 0499 Chinese Buddhist monk Hui Shen reputed to have sailed to Fu-Sang (possibly America) 0500 Beans, corn and squash cultivated in Eastern Woodlands 0875 Irish monks land on Magdalen Islands 0995 Leif Erikson sets out on expedition to Vinland 298 DATE AUTHOR AND TITLE EVENT 1000 Viking settlement at L'Anse aux Meadows, Nfld- possibly Leif Ericson's Vinland Thule culture replaces Dorset culture in Arctic 1390 Mohawk, Oneida, Cayuga, Onondaga and Seneca establish the Iroquois confederacy (Tuscarora join in 1722) 1400 West Coast tribes establish trading network 1431 Joan of Arc is burned at Rauen 1497 John Cabot discovers the Grand Banks 1504 Est. of StJohn's as English fisheries base in Newfoundland 1513 Balboa crosses Panama to the Pacific 1516 More: Utopia 1517 Beginnings of Protestant Reformation 1519 Cortez conquers Mexico 1526 Founding of the Moghul Empire 1532 Machiavelli: The Prince Rabelais: Pantagruel 1534 Est. ofJesuit order Jacques Cartier explores St Lawrence River 1537 Est. of Ursuline order 1541 John Calvin introduces Reformation into Geneva 1544 English translation of the Bible 1556 Ramusio's Italian translation of Cartier's journal 1564 D. -

Governor General's Literary Awards

Governor General’s Literary Awards | Prix littéraires du Gouverneur géneral Year/Année Category/Catégorie Laureates/Lauréats Children’s Literature – Illustrated JonArno Lawson for / pour Sidewalk Flowers 2015 Books (Groundwood Books / House of Anansi Press) Children’s Literature – Text Caroline Pignat for / pour The Gospel Truth (Red Deer Press) Drama David Yee for / pour carried away on the crest of a wave (Playwrights Canada Press) Essais Jean-Philippe Warren for / pour Honoré Beaugrand : la plume et l'épée (1848-1906) (Les Éditions du Boréal) Fiction Guy Vanderhaeghe for / pour Daddy Lenin and Other Stories (McClelland & Stewart / Penguin Random House Canada) Littérature jeunesse – livres André Marois for / pour Le voleur de sandwichs (Les illustrés Éditions de la Pastèque) Littérature jeunesse – livres Patrick Doyon for / pour Le voleur de sandwichs (Les illustrés Éditions de la Pastèque) Littérature jeunesse – texte Louis-Philippe Hébert for / pour Marie Réparatrice (Les Éditions de La Grenouillère) Non-fiction Mark L. Winston for / pour Bee Time: Lessons from the Hive (Harvard University Press) Poésie Joël Pourbaix for / pour Le mal du pays est un art oublié (Éditions du Noroît) Poetry Robyn Sarah for / pour My Shoes Are Killing Me (Biblioasis) Romans et nouvelles Nicolas Dickner for / pour Six degrés de liberté (Éditions Alto) Théâtre Fabien Cloutier for / pour Pour réussir un poulet (Les éditions de L'instant même et Dramaturges Éditeurs) Traduction de l’anglais vers le Lori Saint-Martin for / pour Solomon Gursky (Les français -

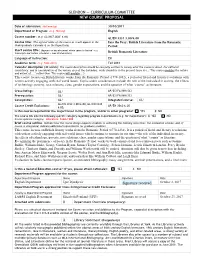

Glendon — Curriculum Committee New Course Proposal

GLENDON — CURRICULUM COMMITTEE NEW COURSE PROPOSAL Date of submission: (dd/mm/yy) 30/10/2017 Department or Program: (e.g. History) English Course number: (e.g. GL/HIST 2XXX 6.00) GL/EN 3331 3.00/6.00 Course title: (The official name of the course as it will appear in the Into the Fray: British Literature from the Romantic Undergraduate Calendar & on the Repository) Period Short course title: (Appears on any document where space is limited - e.g. transcripts and lecture schedules — max 40 characters) British Romantic Literature Language of instruction: EN Academic term: (e.g. FALL 2012) Fall 2018 Calendar description (40 words): The course description should be carefully written to convey what the course is about. For editorial consistency, and in consideration of the various uses of the Calendars, verbs should be in the present tense (i.e., "This course analyzes the nature and extent of...," rather than "This course will analyze...") This course focuses on British literary works from the Romantic Period (1770-1832), a period of literal and literary revolutions with writers actively engaging with real world issues. Topics under consideration include the role of the individual in society, the effects of technology, poverty, race relations, class, gender expectations, and the question of what “counts” as literature. Cross-listings: GL/ AP/ES/FA/HH/SC/ Prerequisites: GL/ AP/ES/FA/HH/SC/ Corequisites: GL/ Integrated course: GS/ GL/EN 3322 3.00/6.00; GL/EN 3330 Course Credit Exclusions: AP/EN 3560 6.00 6.00; Is this course required for the major/minor in the program, and/or in other programs? YES X NO The course fits into the following specific category regarding program requirements (e.g.