Fellowship Bible Church

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jacob Goes to Haran

Jacob Goes to Haran Scripture Reference: Genesis 28:10-33:20 and Genesis 35:1-12. Suggested Emphasis or Theme: Sometimes we learn lessons from bad things that happen to us. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. ….. Story Overview: Having deceived his brother and father Jacob escaped to relatives in Haran. During the journey Jacob dreamed of a stairway between heaven and earth on which angels were ascending and descending to the Lord at the top. God reassured Jacob of his blessing and promise. Undeserving as he was this promise sustained Jacob over the next twenty years as he worked for his uncle Laban and built a family and wealth. Eventually, Jacob returned to his home and was surprised to find that his brother, Esau, welcomed him with open arms. Background Study: This lesson takes up where the story of Jacob, Esau and the Birthright left off. After deceiving his father and brother Jacob left his family home and makes his way North to his mother’s relatives in Haran. The official reason that he is looking for a wife but it is evident that he is fleeing the wrath of his brother. Many important events happen on his trip to Haran, his life there and years later upon his eventual return to face his brother. The following events begin and end in Bethel. Jacob’s Stairway Dream at Bethel (Genesis 28:10-22) Jacob Meets His Relatives in Haran (Genesis 29:1-14) Jacob is Tricked by Laban and Marries both Rachel and Leah (Genesis 29:14-30) Jacob’s Children are Born (Genesis 29:31-30:4) Jacob Schemes and Increases His Flocks (Genesis 30:25-43) Jacob Flees and Laban Pursues (Genesis 31:1-55) Jacob Prepares to Meet Esau Again (Genesis 32:1-21) Jacob Wrestles With God (Genesis 32:22-32) Jacob and Esau Make Peace (Genesis 33:1-20) Eventually, Jacob Becomes “Israel” and Moves to Bethel (Genesis 35:1-12) Although there are many important events that take place in Genesis 28-33 trying to cover all of them in one lesson would be confusing. -

French Guineas Sweep for Godolphin Cont

MONDAY, 13 MAY 2019 CLEAN SWEEP FOR O=BRIEN FRENCH GUINEAS SWEEP By Tom Frary FOR GODOLPHIN AThere are a lot of horses there@, commented Aidan O=Brien in his typically understated way at Leopardstown on Sunday as he pondered the stable=s tsunami of Epsom Derby hopefuls including the easy G3 Derrinstown Stud Derby Trial S. scorer Broome (Ire) (Australia {GB}). Ballydoyle have now won every recognised Derby trial in Britain and Ireland in 2019 and this talented and progressive colt is responsible for two having rated a very impressive winner of the Apr. 6 G3 Ballysax S. over this course and distance. Uncovering which of the yard=s plethora of contenders for the blue riband will come out on top was an already taxing pursuit, but after another convincing prep performance from Broome it is fitting more into the unsolvable conundrum criteria. Cont. p6 Persian King justifies favouritism in the Poulains | Scoop Dyga By Tom Frary IN TDN AMERICA TODAY Testing conditions at ParisLongchamp on Sunday created by a THE WEEK IN REVIEW deluge of rain meant that equine pyrotechnics were unlikely With litigation likely in the wake of a controversial finish to the despite the formidable presence of Persian King (Ire) (Kingman GI Kentucky Derby, fans should get tied on for a long ride. {GB}). Hot favourite for the G1 The Emirates Poule d=Essai des Click or tap here to go straight to TDN America. Poulains, Godolphin and Ballymore Thoroughbred Ltd=s >TDN Rising Star= duly won, but it was more a case of a thankless task being carried out in professional manner as he delivered a first Classic success for his exhilarating sire. -

Chayei Sara 5769

A Muse: Chayei Sarah “Then Rebecca arose with her maidens; they rode upon the camels and proceeded after the man; the servant took Rebecca and went. Now Isaac came from having gone to Beer-lahai-roi, for he dwelt in the south of the country. Isaac went out to supplicate in the fields towards evening and he raised his eyes and saw, and behold! Camels were coming. And Rebecca raised her eyes and saw Isaac; she fell while on the camel and she said to the servant who is that man walking in the field toward us? And the servant said ‘he is my master’. She took the veil and covered herself. The servant told Isaac all the things he had done. And Isaac brought her in to the tent of Sarah his mother; he married Rebecca, she became his wife and he loved her…” (Genesis 24:61-67) This narrative while providing some information leaves out a lot of the detail, thus presenting a sketchy picture which begs to be filled in and texturized. The Torah doesn’t elaborate on Rebecca’s journey back to Isaac, or the dynamics between Rebecca and Eliezer, Isaac’s servant during the course of the journey. It appears as though the narrative was holding back some of the details. The text provides some vague information about Isaac going out to the field to “supplicate”, and later the text even relates that Eliezer informs Isaac of everything that happened on the journey. What did happen? This, the text doesn’t reveal. Some of the language employed in the text is problematic as well. -

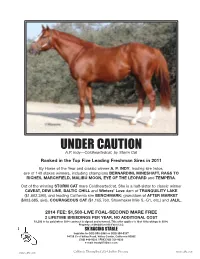

UNDER CAUTION:Layout 1 12/4/13 10:08 AM Page 1

UNDER CAUTION:Layout 1 12/4/13 10:08 AM Page 1 UNDER CAUTION A.P. Indy—Coldheartedcat, by Storm Cat Ranked in the Top Five Leading Freshman Sires in 2011 By Horse of the Year and classic winner A. P. INDY, leading sire twice, sire of 140 stakes winners, including champions BERNARDINI, MINESHAFT, RAGS TO RICHES, MARCHFIELD, MALIBU MOON, EYE OF THE LEOPARD and TEMPERA. Out of the winning STORM CAT mare Coldheartedcat. She is a half-sister to classic winner CAVEAT, DEW LINE, BALTIC CHILL and Winters’ Love dam of TRANQUILITY LAKE ($1,662,390), and leading California sire BENCHMARK; granddam of AFTER MARKET ($903,685, sire), COURAGEOUS CAT ($1,165,760, Shoemaker Mile S.-G1, etc.) and JALIL. 2014 FEE: $1,500-LIVE FOAL-SECOND MARE FREE 2 LIFETIME BREEDINGS PER YEAR, NO ADDITIONAL COST $1,500 to be paid when 2014 contract is signed and returned. This offer applies to first 10 bookings in 2014. Property of Medallion Hill Farm LLC SK RACING STABLE Inquiries to (925) 550-2383 or (925) 354-5237 14728 Cool Valley Road, Valley Center, California 92082 (760) 443-9523 / FAX (760) 751-9523 e-mail: [email protected] 184 www.ctba.com California Thoroughbred 2014 Stallion Directory www.ctba.com UnderCautioncs406201ORIGJockeyClubPageSent11-8-2013-NoChange11-27-2013-1245pm :Layout 1 11/27/13 12:48 PM Page1 UNDER CAUTION 2001 Chestnut - Height 16.1 - Dosage Profile: 7-14-19-0-0; DI: 3.21; CD: +0.70 RACE AND (STAKES) RECORD Bold Ruler Boldnesian Age Starts 1st 2nd 3rd Earnings Alanesian Bold Reasoning 2 3 1 0 0 $18,300 Hail to Reason 61 foals, 10 SWs 3 3 0 1 0 2,200 Reason to Earn Sailing Home Seattle Slew Round Table 4 11 2 1 1 36,045 1050 foals, 114 SWs Poker Glamour 5 14 2 1 3 41,700 My Charmer Jet Action 31 5 3 4 $98,245 12 foals, 4 SWs Fair Charmer Myrtle Charm A.P. -

Women of the Bible Dinah & Tamar Pastor Ritva Williams March 2016 � � RECAP Rebekakh Sends Jacob to Haran to Marry One of Her Brother, Laban’S Daughters

Women of the Bible Dinah & Tamar Pastor Ritva Williams March 2016 ! ! RECAP Rebekakh sends Jacob to Haran to marry one of her brother, Laban’s daughters. Jacob falls in love with Rachel, and offers to work for 7 years in exchange for Rachel’s hand in marriage. Laban agrees, but on their wedding night substitutes Leah for Rachel, excusing his deceit by asserting that it is not proper for the younger girl to marry before the elder. In !order to marry Rachel, Jacob works another 7 years. ! • Bride price = money, property, goods, or in this case 7 years of (unpaid) labor given by the groom (groom’s family) to the bride’s family. In tribal societies bride price is often explained as compensation for the loss of the bride’s labor and fertility within her kin group. • Dowry = a bride’s share of her family’s wealth, e.g. money, property, goods, or in the case of Leah and Rachel, the slaves/servants their father gives them when they marry. Leah! is unloved but highly fertile. Rachel is dearly loved but infertile. Their relationship is one of rivalry for Jacob’s attention, respect, and love in which the sisters come to use their slaves, Bilhah and Zilpah, as surrogate mothers. The result: ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! In order to provide for his growing household, Jacob makes a deal with Laban whereby his wages will consist of all the newborn speckled, spotted, or black sheep and goats. Through careful breeding practices, Jacob becomes “exceedingly rich,” making his in-laws envious. After consulting with Leah and Rachel, Jacob takes his wives and children, and heads back to Canaan. -

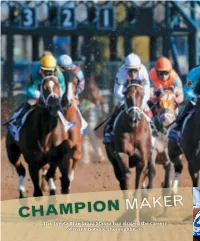

Champion Maker

MAKER CHAMPION The Toyota Blue Grass Stakes has shaped the careers of many notable Thoroughbreds 48 SPRING 2016 K KEENELAND.COM Below, the field breaks for the 2015 Toyota Blue Grass Stakes; bottom, Street Sense (center) loses a close 2007 running. MAKER Caption for photo goes here CHAMPION KEENELAND.COM K SPRING 2016 49 RICK SAMUELS (BREAK), ANNE M. EBERHARDT CHAMPION MAKER 1979 TOBY MILT Spectacular Bid dominated in the 1979 Blue Grass Stakes before taking the Kentucky Derby and Preakness Stakes. By Jennie Rees arl Nafzger’s short list of races he most send the Keeneland yearling sales into the stratosphere. But to passionately wanted to win during his Hall show the depth of the Blue Grass, consider the dozen 3-year- of Fame training career included Keeneland’s olds that lost the Blue Grass before wearing the roses: Nafzger’s Toyota Blue Grass Stakes. two champions are joined by the likes of 1941 Triple Crown C winner Whirlaway and former record-money earner Alysheba Instead, with his active trainer days winding down, he has had to (disqualified from first to third in the 1987 Blue Grass). settle for a pair of Kentucky Derby victories launched by the Toyota Then there are the Blue Grass winners that were tripped Blue Grass. Three weeks before they entrenched their names in his- up in the Derby for their legendary owners but are ensconced tory at Churchill Downs, Unbridled finished third in the 1990 Derby in racing lore and as stallions, including Calumet Farm’s Bull prep race, and in 2007 Street Sense lost it by a nose. -

Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’S Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes

Northern Dancer 90th May 2, 1964 THE WINNER’S PEDIGREE AND CAREER HIGHLIGHTS Pharos Nearco Nogara Nearctic *Lady Angela Hyperion NORTHERN DANCER Sister Sarah Polynesian Bay Colt Native Dancer Geisha Natalma Almahmoud *Mahmoud Arbitrator YEAR AGE STS. 1ST 2ND 3RD EARNINGS 1963 2 9 7 2 0 $ 90,635 1964 3 9 7 0 2 $490,012 TOTALS 18 14 2 2 $580,647 At 2 Years WON Summer Stakes, Coronation Futurity, Carleton Stakes, Remsen Stakes 2ND Vandal Stakes, Cup and Saucer Stakes At 3 Years WON Kentucky Derby, Flamingo Stakes, Florida Derby, Blue Grass Stakes, Preakness, Queen’s Plate 3RD Belmont Stakes Horse Eq. Wt. PP 1/4 1/2 3/4 MILE STR. FIN. Jockey Owner Odds To $1 Northern Dancer b 126 7 7 2-1/2 6 hd 6 2 1 hd 1 2 1 nk W. Hartack Windfields Farm 3.40 Hill Rise 126 11 6 1-1/2 7 2-1/2 8 hd 4 hd 2 1-1/2 2 3-1/4 W. Shoemaker El Peco Ranch 1.40 The Scoundrel b 126 6 3 1/2 4 hd 3 1 2 1 3 2 3 no M. Ycaza R. C. Ellsworth 6.00 Roman Brother 126 12 9 2 9 1/2 9 2 6 2 4 1/2 4 nk W. Chambers Harbor View Farm 30.60 Quadrangle b 126 2 5 1 5 1-1/2 4 hd 5 1-1/2 5 1 5 3 R. Ussery Rokeby Stables 5.30 Mr. Brick 126 1 2 3 1 1/2 1 1/2 3 1 6 3 6 3/4 I. -

Part 3 BECOMING a FRIEND of the FAITHFUL GOD a STUDY on ABRAHAM

Part 3 Becoming a Friend of the Faithful God A STUDY on Abraham i In & Out® GENESIS Part 3 BECOMING A FRIEND OF THE FAITHFUL GOD A STUDY ON ABRAHAM ISBN 978-1-62119-760-7 © 2015, 2018 Precept Ministries International. All rights reserved. This material is published by and is the sole property of Precept Ministries International of Chattanooga, Tennessee. No part of this publication may be reproduced, translated, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Precept, Precept Ministries International, Precept Ministries International The Inductive Bible Study People, the Plumb Bob design, Precept Upon Precept, In & Out, Sweeter than Chocolate!, Cookies on the Lower Shelf, Precepts For Life, Precepts From God’s Word and Transform Student Ministries are trademarks of Precept Ministries International. Unless otherwise noted, all Scripture quotations are from the New American Standard Bible, ©1960, 1962, 1963, 1968, 1971, 1972, 1973, 1975, 1977, 1995 by the Lockman Foundation. Used by permission. www.lockman.org 2nd edition Printed in the United States of America ii CONTENTS PAGE CONTENTS L ESSONS 1 LESSON ONE: An Extraordinary Promise 9 LESSON TWO: Covenant with God 17 LESSON THREE: “Is anything too difficult for the LORD?” 21 LESSON FOUR: What Does God Say about Homosexuality? 27 LESSON FIVE: Is There a Bondwoman in Your Life? 35 LESSON SIX: The Promised Son A PPENDIX 40 Explanations of the New American Standard Bible Text Format 41 Observation Worksheets 77 Abraham’s Family Tree 79 Journal on God 83 From Ur to Canaan 84 Abraham’s Sojournings 85 Genesis 1–25 at a Glance iii iv Precept Ministries International Becoming a Friend P.O. -

COOL SLEW Barn 22 Hip No. 3671

Consigned by Hill 'n' Dale Sales Agency, Agent Hip No. COOL SLEW Barn 3671 Dark Bay or Brown Mare; foaled 1999 22 Boldnesian Bold Reasoning ................ Reason to Earn Seattle Slew ...................... Poker My Charmer ...................... Fair Charmer COOL SLEW Cannonade Caveat .............................. Cold Hearted Icy Warning ...................... (1990) Northern Jove Northern Sting .................. Suebee By SEATTLE SLEW (1974). Horse of the year, Triple Crown winner of $1,208,- 726, Kentucky Derby -G1 , etc. Leading sire, sire of 24 crops of racing age, 1103 foals, 783 starters, 111 black-type winners, 8 champions, 537 win - ners of 1544 races and earning $83,853,811. Leading broodmare sire 3 times in U.S. and U.A.E., sire of dams of 221 black-type winners, including champions Cigar, Lemon Drop Kid, Hishi Akebono, Kawakami Princess, Escena, Golden Attraction, Mulca, Slew of Reality (ARG), Hello Seattle. 1st dam ICY WARNING , by Caveat. 9 wins, 2 to 6, $516,202, River Downs Budweiser Breeders' Cup S. [L] (RD, $94,620), Variety Queen S.-R (HOL, $31,450), 2nd Nijana S. [G3] , Spicy Living H. [G3] , etc. Sister to OPS SMILE [G1] ($785,246), Northern Flair , half-sister to TESTING [L] ($544,945). Dam of 13 registered foals, 13 of racing age, 11 to race, 8 winners, incl.-- SNOW CONE (f. by Cryptoclearance). 4 wins, 2 to 4, $353,110, Judy's Red Shoes S. [L] (CRC, $54,500), GTOBA Debutante S.-R (CRC, $36,000), 2nd Calder Oaks [L] (CRC, $39,200), South Beach S.-R (GP, $15,000), etc. DEVOTION UNBRIDLED (f. by Unbridled). 4 wins, $163,500, Miss Liberty S. -

Complete Dissertation

VU Research Portal Abraham in Narrative Worldviews: Doing Comparative Theology through Christian- Muslim Dialogue in Turkey Bristow, G.F.V. 2015 document version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in VU Research Portal citation for published version (APA) Bristow, G. F. V. (2015). Abraham in Narrative Worldviews: Doing Comparative Theology through Christian- Muslim Dialogue in Turkey. General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in the public portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from the public portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal ? Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. E-mail address: [email protected] Download date: 03. Oct. 2021 VRIJE UNIVERSITEIT Abraham in Narrative Worldviews: Doing Comparative Theology through Christian-Muslim Dialogue in Turkey ACADEMISCH PROEFSCHRIFT ter verkrijging van de graad Doctor aan de Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, op gezag van de rector magnificus prof.dr. F.A. van der Duyn Schouten, in het openbaar te verdedigen ten overstaan van de promotiecommissie van de Faculteit der Godgeleerdheid op donderdag 28 mei, 2015 om 11.45 uur in de aula van de universiteit, De Boelelaan 1105 door George Farquhar Vance Bristow Jr geboren te Pennsylvania, Verenigde Staten promotoren: prof.dr. -

Heavenly Priesthood in the Apocalypse of Abraham

HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM The Apocalypse of Abraham is a vital source for understanding both Jewish apocalypticism and mysticism. Written anonymously soon after the destruction of the Second Jerusalem Temple, the text envisions heaven as the true place of worship and depicts Abraham as an initiate of the celestial priesthood. Andrei A. Orlov focuses on the central rite of the Abraham story – the scapegoat ritual that receives a striking eschatological reinterpretation in the text. He demonstrates that the development of the sacerdotal traditions in the Apocalypse of Abraham, along with a cluster of Jewish mystical motifs, represents an important transition from Jewish apocalypticism to the symbols of early Jewish mysticism. In this way, Orlov offers unique insight into the complex world of the Jewish sacerdotal debates in the early centuries of the Common Era. The book will be of interest to scholars of early Judaism and Christianity, Old Testament studies, and Jewish mysticism and magic. ANDREI A. ORLOV is Professor of Judaism and Christianity in Antiquity at Marquette University. His recent publications include Divine Manifestations in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Selected Studies in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2009), Concealed Writings: Jewish Mysticism in the Slavonic Pseudepigrapha (2011), and Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology (2011). Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. http://ebooks.cambridge.org/ebook.jsf?bid=CBO9781139856430 Cambridge Books Online © Cambridge University Press, 2013 HEAVENLY PRIESTHOOD IN THE APOCALYPSE OF ABRAHAM ANDREI A. ORLOV Downloaded from Cambridge Books Online by IP 130.209.6.50 on Thu Aug 08 23:36:19 WEST 2013. -

THE Cupolacooperstown, New York Vol

The Bulletin of The Medical Alumni Association of Bassett Medical Center Summer 2020 THE CUPOLACooperstown, New York Vol. XXIV No. 2 A Tribute to Theodore (Ted) Peters, Jr., Ph.D., (1922 – 2020) Bassett’s Selfless Biochemist Extraordinaire Theodore (Ted) Peters, Jr., Ph.D., Soft spoken, cheerful, and always humble, Ted Peters “retired” arrived in Cooperstown with his family in 1988 but did not leave his office as research emeritus until in 1955, recruited to The Mary Imogene about 2010. He was incredibly helpful to thousands of individuals Bassett Hospital from Harvard Medical through his years of research, clinical and administrative roles School by research physician, Joe at Bassett and in the wider Cooperstown community. Ferrebee, M.D., his former Harvard In a recent letter to John Davis, M.D., William (Buck) Greenough, colleague. As Peters recalled in an M.D., research fellow assigned to Bassett by the U.S. Public interview years later, “I wondered Research Service (1959-61) and currently professor of Medicine what kind of a wilderness this is at The Johns Hopkins School of Medicine, put it this way: “In we’re going to?” July of 1959, I arrived in Cooperstown with my wife, Jane and Hired as research biochemist, three young children. Ted Peters made time and met with me Peters soon teamed up with weekly to teach me the mysteries of protein chemistry… He associate pathologist Charles Ashley, was always available to me and helped enormously as I carried M.D., to use the institution’s new out experiments seeking a protein precursor in hemoglobin electron microscope for enhancing synthesis.