App. 1 DA 17-0603 in the SUPREME COURT of the STATE OF

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Unofficial 2018 General Election Results

Unofficial 2018 General Election Results Updated 11/13/2018 POSITION AND CANDIDATES WHO HAVE FILED TERM LENGTH TOTAL # OF UNITED STATES SENATOR 6 YEAR TERM VOTES RICK BRECKENRIDGE LIBERTARIAN 227 MATT ROSENDALE REPUBLICAN 3854 JON TESTER DEMOCRAT 2070 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 2 YEAR TERM GREG GIANFORTE REPUBLICAN 4075 ELINOR SWANSON LIBERTARIAN 210 KATHLEEN WILLIAMS DEMOCRAT 1852 CLERK OF THE SUPREME COURT 6 YEAR TERM BOWEN GREENWOOD REPUBLICAN 3969 REX RENK DEMOCRAT 1501 ROGER ROOTS LIBERTARIAN 373 SUPREME COURT JUSTICE #4 8 YEAR TERM BETH BAKER - YES N/P 4234 BETH BAKER - NO N/P 1127 SUPREME COURT JUSTICE #2 8 YEAR TERM INGRID GUSTAFSON - YES N/P 4125 INGRID GUSTAFSON - NO N/P 1166 20TH DISTRICT COURT JUDGE, DEPT 2 6 YEAR TERM DEBORAH "KIM" CHRISTOPHER N/P 3733 ASHLEY D MORIGEAU N/P 1803 STATE REPRESENTATIVE - HOUSE DISTRICT 13 2 YEAR TERM BOB BROWN REPUBLICAN 2592 CHRIS GROSS DEMOCRAT 986 Unofficial 2018 General Election Results Updated 11/13/2018 POSITION AND CANDIDATES WHO HAVE FILED TERM LENGTH TOTAL # OF STATE REPRESENTATIVE - HOUSE DISTRICT 14 DENLEY M. LOGE REPUBLICAN 1790 DIANE L. MAGONE DEMOCRAT 633 COMMISSIONER Dist #1 6 YEAR TERM CAROL A. BROOKER N/P 3129 PAUL C FIELDER N/P 2785 COUNTY CLERK & RECORDER/TREASURER / SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS 4 YEAR TERM NICHOL SCRIBNER N/P 4811 COUNTY SHERIFF/CORONER 4 YEAR TERM DARLENE LEE N/P 1598 TOM RUMMEL N/P 4350 COUNTY ATTORNEY/PUBLIC ADMINISTRATOR 4 YEAR TERM NAOMI R. LEISZ N/P 4557 JUSTICE OF THE PEACE 4 YEAR TERM DOUGLAS DRYDEN N/P 3641 MARK T FRENCH N/P 2054 LEGISLATIVE REFERENDUM NO. -

R--6Ta•--Df Clerk Justice Ingrid Gustafson Delivered the Opinion of the Court

10/15/2019 DA 18-0573 Case Number: DA 18-0573 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF MONTANA 2019 MT 249N GEO R. PIERCE, INC., Plaintiff and Appellee, v. PAMELA JO POLEJEWSKI, Defendant and Appellant. APPEAL FROM: District Court of the Eighth Judicial District, In and For the County of Cascade, Cause No. DDV 18-0201(b) Honorable Elizabeth A. Best, Presiding Judge COUNSEL OF RECORD: For Appellant: Pamela Jo Polejewski, Self-represented, Great Falls, Montana For Appellee: Kelly J. Varnes, Hendrickson Law Firm, P.C., Billings, Montana Submitted on Briefs: September 25, 2019 Decided: October 15, 2019 Filed: __________________________________________r--6ta•--df Clerk Justice Ingrid Gustafson delivered the Opinion of the Court. ¶1 Pursuant to Section I, Paragraph 3(c), Montana Supreme Court Internal Operating Rules, this case is decided by memorandum opinion and shall not be cited and does not serve as precedent. Its case title, cause number, and disposition shall be included in this Court’s quarterly list of noncitable cases published in the Pacific Reporter and Montana Reports. ¶2 Pamela Jo Polejewski, appearing pro se, appeals the September 5, 2018 Order Affirming Justice Court Ruling from the Eighth Judicial District Court, Cascade County. Geo R. Pierce, Inc., sued Polejewski for damages and to recover possession of a storage container, when Polejewski failed to make monthly payments on a two-year purchase option lease agreement for the storage container. The Justice Court issued its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law and Judgment on March 9, 2018. Polejewski raises various claims challenging the award of $3,850 in damages, plus attorney fees and costs, as well as awarding possession of the storage container at issue to Geo R. -

Initial Report to the 67Th Montana Legislature

April 2021 SPECIAL JOINT SELECT COMMITTEE ON JUDICIAL TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY INITIAL REPORT TO THE 67TH MONTANA LEGISLATURE INITIAL REPORT ON JUDICIAL TRANSPARENCY AND ACCOUNTABILITY 1 The 67th Montana Legislature PAGE HELD FOR FINAL TABLE OF CONTENTS 2 The 67th Montana Legislature SPECIAL JOINT SELECT COMMITTEE ON JUDICIAL ACCOUNTABILITY AND TRANSPARENCY COMMITTEE MEMBERS The President of the Senate and the Speaker of the House created the Special Joint Select Committee on Judicial Transparency and Accountability on April 14, 2021. Senate Members House Members Senator Greg Hertz, Chair Representative Sue Vinton, Vice Chair Polson, MT Billings, MT Ph: (406) 253-9505 Ph: (406) 855-2625 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Senator Tom McGillvray Representative Amy Regier Billings, MT Kalispell, MT Ph: (406) 698-4428 Ph: (406) 253-8421 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Senator Diane Sands Representative Kim Abbott Missoula, MT Helena, MT Ph: (406) 251-2001 Ph: (406) 439-8721 Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 3 The 67th Montana Legislature Introduction. This report is a summary of the work of the Special Joint Select Committee on Judicial Accountability and Transparency. Members received additional information and testimony during their investigation, and this report is an effort to highlight key information and the processes followed by the Select Committee in reaching its conclusions. To review additional information, including audio minutes, and exhibits, visit -

Rocket Docket Hon. Jason Marks Fourth Judicial District Missoula, MT

MRCP Rule 6 – Rocket Docket Hon. Jason Marks Fourth Judicial District Missoula, MT Dylan McFarland Knight Nicastro LLC Missoula, MT Moderator: Lindsay Ward, Helena Pre-Litigation MTLA Spring 2021 Seminar – April 23, 2021 Live Streaming Only 10/29/2019 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF MONTANA Case Number: AF 07-0110 AF 07-0110 IN RE THE MONTANA UNIFORM O R D E R DISTRICT COURT RULES On May 2, 2019, the Uniform District Court Rules Commission submitted proposed revisions to the Montana Uniform District Court Rules. The Court opened a 60-day comment period on the revisions, and after review and consideration of the revisions in a public meeting held on September 24, 2019, the Court determined the revisions were well taken, and approved them with some revisions. IT IS ORDERED that the proposed revisions as approved by the Court are ADOPTED. The Montana Uniform District Court Rules are amended to read as shown in the attachment to this Order, effective January 1, 2020. This Order and the attached rules shall be posted on the Court’s website. In addition, the Clerk is directed to provide copies of this Order and the attachment to the State Law Library, to Todd Everts and Connie Dixon at Montana Legislative Services, to Chad Thomas at Thomson Reuters, to Patti Glueckert and the Statute Legislation department at LexisNexis, and to the State Bar of Montana, with the request that the State Bar provide notice of the revised rules on its website and in the next available issue of the Montana Lawyer. -

2018 General Election Candidate List (Note: This List Contains the Federal, State, State District, and Legislative Races)

2018 General Election Candidate List (Note: This list contains the federal, state, state district, and legislative races) Federal, State, and State District Candidates Office Name Incumbent? Party Mailing Address City State Zip Phone Email Web Address US Senate Rick Breckenridge L PO Box 181 Dayton MT 59914 261-7758 [email protected] mtlp.org US Senate Matt Rosendale R 1954 Hwy 16 Glendive MT 59330 763-1234 [email protected] mattformontana.com US Senate Jon Tester YD 709 Son Lane Big Sandy MT 59520 378-3182 [email protected] jontester.com US House Greg Gianforte YR PO Box 877 Helena MT 59624 414-7150 [email protected] www.gregformontana.com US House Elinor Swanson L PO Box 20562 Billings MT 59104 598-0515 [email protected] www.swanson4liberty.com US House Kathleen Williams D PO Box 548 Bozeman MT 59771 686-1633 [email protected] kathleenformontana.com Public Service Commissioner #1 Doug Kaercher D PO Box 1707 Havre MT 59501 265-1009 [email protected] Not Provided Public Service Commissioner #1 Randy Pinocci R 66 Sun River Cascade Road Sun River MT 59483 264-5391 [email protected] Not Provided Public Service Commissioner #5 Brad Johnson YR 3724B Old Hwy 12 E East Helena MT 59635 422-5933 [email protected] Not Provided Public Service Commissioner #5 Andy Shirtliff D 1319 Walnut Street #1 Helena MT 59601 249-4546 [email protected] andyshirtliff.com Clerk of the Supreme Court Bowen Greenwood R 415 Cat Avenue #A Helena MT 59602 465-1578 [email protected] greenwoodformontana.com Clerk of the Supreme Court Rex Renk D PO Box 718 Helena MT 59624 459-7196 [email protected] www.rexformontana.com Clerk of the Supreme Court Roger Roots L 113 Lake Drive East Livingston MT 59047 224-3105 [email protected] rogerroots.com Supreme Court Justice #4 Beth Baker Y NP PO Box 897 Helena MT 59624 Not Listed [email protected] bakerforjustice.com Supreme Court Justice #2 Ingrid Gustafson Y NP 626 Lavender St. -

App. 1 in the SUPREME COURT of the STATE of MONTANA DA 17

App. 1 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF MONTANA DA 17-0492 ----------------------------------------------------------------------- KENDRA ESPINOZA, JERI ELLEN ANDERSON and JAIME SCHAEFER, Plaintiffs and Appellees, v. ORDER MONTANA DEPARTMENT (Filed Jan. 24, 2019) OF REVENUE and GENE WALBORN, in his official capacity as DIRECTOR of the MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF REVENUE, Defendants and Appellants. ----------------------------------------------------------------------- On December 12, 2018, this Court issued its Opin- ion in Espinoza v. Mont. Dep’t of Revenue, 2018 MT 306, 393 Mont. 466, ___ P.3d ___, concluding that § 15-30- 3111, MCA (the Tax Credit Program), was unconstitu- tional because it violated Article X, Section 6, of the Montana Constitution. Appellees (collectively, Plain- tiffs) filed a Motion to Stay Judgment Pending United States Supreme Court Review. Appellant, the Depart- ment of Revenue (the Department), filed a response in- dicating it does not oppose a reasonable stay to allow for efficient administration of the Tax Credit Program. The Department represents that it has already com- pleted state tax returns, forms, and instructions for tax App. 2 year 2018, which provide taxpayers with the ability to claim tax credits based on their donations to Student Scholarship Organizations. The Department repre- sents that the most efficient course of action would be for it to administer the Tax Credit Program in tax year 2018. This Court has authority to stay or postpone judgment to prevent disruption of the Department’s efficient administration of the Tax Credit Program. See Mont. Cannabis Indus. Ass’n, 382 Mont. 297, 297a- 297d, 368 P.3d 1131, 1161-63 (April 25, 2016); Helena Elementary Sch. -

Unofficial 2018 General Election Results

Unofficial 2018 General Election Results Updated 11/06/2018 POSITION AND CANDIDATES WHO HAVE FILED TERM LENGTH TOTAL # OF UNITED STATES SENATOR 6 YEAR TERM VOTES RICK BRECKENRIDGE LIBERTARIAN 225 MATT ROSENDALE REPUBLICAN 3829 JON TESTER DEMOCRAT 2047 UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE 2 YEAR TERM GREG GIANFORTE REPUBLICAN 4047 ELINOR SWANSON LIBERTARIAN 206 KATHLEEN WILLIAMS DEMOCRAT 1834 CLERK OF THE SUPREME COURT 6 YEAR TERM BOWEN GREENWOOD REPUBLICAN 3942 REX RENK DEMOCRAT 1486 ROGER ROOTS LIBERTARIAN 368 SUPREME COURT JUSTICE #4 8 YEAR TERM BETH BAKER - YES N/P 4202 BETH BAKER - NO N/P 1114 SUPREME COURT JUSTICE #2 8 YEAR TERM INGRID GUSTAFSON - YES N/P 4094 INGRID GUSTAFSON - NO N/P 1152 20TH DISTRICT COURT JUDGE, DEPT 2 6 YEAR TERM DEBORAH "KIM" CHRISTOPHER N/P 3713 ASHLEY D MORIGEAU N/P 1783 STATE REPRESENTATIVE - HOUSE DISTRICT 13 2 YEAR TERM BOB BROWN REPUBLICAN 2584 CHRIS GROSS DEMOCRAT 981 Unofficial 2018 General Election Results Updated 11/06/2018 POSITION AND CANDIDATES WHO HAVE FILED TERM LENGTH TOTAL # OF STATE REPRESENTATIVE - HOUSE DISTRICT 14 DENLEY M. LOGE REPUBLICAN 1767 DIANE L. MAGONE DEMOCRAT 620 COMMISSIONER Dist #1 6 YEAR TERM CAROL A. BROOKER N/P 3102 PAUL C FIELDER N/P 2768 COUNTY CLERK & RECORDER/TREASURER / SUPERINTENDENT OF SCHOOLS 4 YEAR TERM NICHOL SCRIBNER N/P 4770 COUNTY SHERIFF/CORONER 4 YEAR TERM DARLENE LEE N/P 1579 TOM RUMMEL N/P 4323 COUNTY ATTORNEY/PUBLIC ADMINISTRATOR 4 YEAR TERM NAOMI R. LEISZ N/P 4518 JUSTICE OF THE PEACE 4 YEAR TERM DOUGLAS DRYDEN N/P 3615 MARK T FRENCH N/P 2035 LEGISLATIVE REFERENDUM NO. -

Download Case

DA 18-0462 04/09/2019 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF MONTANA Case Number: DA 18-0462 2019 MT 81 UPPER MISSOURI WATERKEEPER, Plaintiff and Appellant, v. MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY, Defendant and Appellee, FILED and APR 0 9 2019 THE CITY OF BILLINGS, Eiow..rn Greenwood Clerk of Supreme Court State nf montena Defendant, Intervenor and Appellee. APPEAL FROM: District Court of the Eighteenth Judicial District, In and For the County of Gallatin, Cause No. DV-16-983B Honorable Rienne H. McElyea, Presiding Judge COUNSEL OF RECORD: For Appellant: Guy Alsentzer, Upper Missouri Waterkeeper, Bozeman, Montana For Appellee: William W. Mercer, Brianne McClafferty, Holland & Hart LLP, Billings, Montana (for City of Billings) Kurt R. Moser, Montana Department of Environmental Quality, Helena, Montana Submitted on Briefs: February 13, 2019 Decided: April 9, 2019 Filed: Clerk Justice Ingrid Gustafson delivered the Opinion of the Court. ¶1 Plaintiff Upper Missouri Waterkeeper (Waterkeeper) appeals the order of the Eighteenth District Court, Gallatin County, denying Waterkeeper's Motion for Summary Judgment, granting the Cross-Motions for Summary Judgment of the Defendant Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and Intervenor-Defendant the City of Billings, and affirming DEQ's decision to issue Montana Pollutant Discharge Elimination System(MPDES) Permit No. MTR040000 (the General Permit). We affirm. ¶2 We restate the issues on appeal as follows: I. nether the General Permit complies with public participation requirements? 2. Whether DEQ's decision to incorporate construction and post-construction storm water pollution controls into the General Permit was unlawful, arbitrary, or capricious? 3. Whether DEQ incorporating Total Maximum Daily Loads (TMDLs) into the General Permit was unlawful, arbitrary, or capricious? 4. -

IN the SUPREME COURT of the STATE of MONTANA Case Number: OP 21-0182 OP 21-0182 ______

04/29/2021 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF MONTANA Case Number: OP 21-0182 OP 21-0182 _________________ HAMLIN CONSTRUCTION AND DEVELOPMENT COMPANY, INC., a Montana Corporation; JERRY HAMLIN and BARBARA HAMLIN, Individually, and as TRUSTEES OF THE HAMLIN FAMILY REVOCABLE LIVING TRUST, Petitioners, O R D E R v. MONTANA FIRST JUDICIAL DISTRICT COURT, LEWIS AND CLARK COUNTY, HON. CHRISTOPHER ABBOTT, Presiding, Respondent. _________________ The above-captioned Petitioners (“Hamlins”), via counsel, seek a writ of supervisory control over the First Judicial District Court, Lewis and Clark County, in its Cause No. DDV-2018-980. Hamlins maintain this case should be consolidated with another case also pending in the First Judicial District Court under Cause No. XBDV-2018-1429. Hamlins have also petitioned for a writ of supervisory control over that matter and have moved this Court to consolidate both petitions for supervisory control. Hamlins further request that this District Court matter be stayed pending the resolution of this petition. Supervisory control is an extraordinary remedy that is sometimes justified when urgency or emergency factors exist making the normal appeal process inadequate, when the case involves purely legal questions, and when the other court is proceeding under a mistake of law and is causing a gross injustice, constitutional issues of state-wide importance are involved, or, in a criminal case, the other court has granted or denied a motion to substitute a judge. M. R. App. P. 14(3). Whether supervisory control is appropriate is a case-by-case decision. Stokes v. Mont. Thirteenth Judicial Dist. Court, 2011 MT 182, ¶ 5, 361 Mont. -

Supreme Court No. DA 19-0553: Opinion

11/17/2020 DA 19-0553 Case Number: DA 19-0553 IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF MONTANA 2020 MT 288 MONTANA ENVIRONMENTAL INFORMATION CENTER, SAVE OUR CABINETS, AND EARTHWORKS, Plaintiffs, Appellees, and Cross-Appellants, v. MONTANA DEPARTMENT OF ENVIRONMENTAL QUALITY and MONTANORE MINERALS CORP., Defendants, Appellants, and Cross-Appellees. APPEAL FROM: District Court of the First Judicial District, In and For the County of Lewis and Clark, Cause No. CDV 2017-641 Honorable Kathy Seeley, Presiding Judge COUNSEL OF RECORD: For Defendants, Appellants, and Cross-Appellees: William W. Mercer, Kyle Anne Gray, Brianne C. McClafferty, Victoria A. Marquis, Holland & Hart LLP, Billings, Montana (for Montanore Minerals Corp.) Kurt R. Moser, Special Assistant Attorney General, Helena, Montana (for Montana Department of Environmental Quality) For Plaintiffs, Appellees, and Cross-Appellants: Katherine O’Brien, Timothy J. Preso, Jenny K. Harbine, Earthjustice Northern Rockies Office, Bozeman, Montana For Amicus Montana Chamber of Commerce: Steven T. Wade, M. Christy S. McCann, Browning, Kaleczyc, Berry & Hoven, P.C., Helena, Montana Submitted on Briefs: July 22, 2020 Decided: November 17, 2020 Filed: __________________________________________c.,.--.6-- 4( Clerk 2 Justice Ingrid Gustafson delivered the Opinion of the Court. ¶1 Defendants, Appellants, and Cross-Appellees Montana Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) and Montanore Minerals Corp. (MMC) appeal the Order on Cross-Motions for Summary Judgment issued by the First Judicial District Court, Lewis and Clark County, on July 24, 2019, which denied DEQ’s and MMC’s cross-motions for summary judgment and vacated DEQ’s 2017 issuance of Montana Pollution Discharge Elimination System (MPDES) Permit No. -

Summit Speaker Bios

Summit Speakers Tina Amberboy has served as the Executive Director of the Supreme Court of Texas Permanent Judicial Commission for Children, Youth and Families (Children’s Commission) and the Court Improvement Director for Texas since 2007. She is responsible for developing and executing strategies of the Children's Commission, as well as the day to day operations of the Commission, which is charged with improving child welfare outcomes for children and families through judicial system reform and leadership. Prior to working for the Supreme Court, she worked as an attorney representing children and parents involved the Texas child welfare system. She earned a Juris Doctorate from Baylor Law School in 1996 and a Bachelor of Arts in Government from the University of Texas at Austin in 1993. Justice Max Baer was elected to the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania in November of 2003, assumed his duties on January 5, 2004 and was retained in 2013. Prior to his elevation to the Supreme Court, Justice Baer served on the Court of Common Pleas of Allegheny County from January of 1990 to December of 2003. He spent the first 9½ of those years in Family Division, and was the Administrative Judge of the Division for 5½ years. During his tenure, Justice Baer implemented far-reaching reforms to both Juvenile Court and Domestic Relations, earning him statewide and national recognition. Justice Baer eventually was assigned to the Civil Division, where he continued to distinguish himself until assuming his new duties on the Supreme Court. In acknowledgement of his innovations in family court, in 1997, Justice Baer was named Pennsylvania’s Adoption Advocate of the Year. -

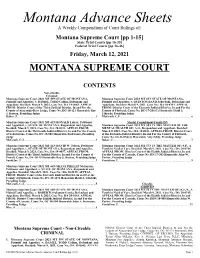

Sample Edition

Montana Advance Sheets A Weekly Compendium of Court Rulings of: Montana Supreme Court [pp 1-15] State Trial Courts [pp 16-35] Federal Trial Courts [pp 36-46] Friday, March 12, 2021 _______________________________________________ MONTANA SUPREME COURT CONTENTS Non-citeable Criminal Montana Supreme Court 2021 MT 59N STATE OF MONTANA, Montana Supreme Court 2021 MT 63N STATE OF MONTANA, Plaintiff and Appellee, v. DANIEL TODD Collins, Defendant and Plaintiff and Appellee, v. QUINTON RAND Sederdahl, Defendant and Appellant. Decided: March 9, 2021. Case No.: DA 19-0643. APPEAL Appellant. Decided: March 9, 2021. Case No.: DA 18-0393. APPEAL FROM: District Court of the Third Judicial District, In and For the FROM: District Court of the Eleventh Judicial District, In and For the County of Anaconda-Deer Lodge, Cause No. DC-18-121 Honorable Ray County of Flathead, Cause No. DC-17-205(C) Honorable Heidi J. J. Dayton, Presiding Judge Ulbricht, Presiding Judge Baker, J. 1 McGrath, C.J. 6 Montana Supreme Court 2021 MT 62N RONALD Latray, Petitioner Mental Commitment/Family/DN and Appellant, v. STATE OF MONTANA, Respondent and Appellee. Montana Supreme Court 2021 MT 58N IN THE MATTER OF THE Decided: March 9, 2021. Case No.: DA 20-0131. APPEAL FROM: MENTAL HEALTH OF: A.O., Respondent and Appellant. Decided: District Court of the Thirteenth Judicial District, In and For the County March 9, 2021. Case No.: DA 19-0141. APPEAL FROM: District Court of Yellowstone, Cause No. DV 19-985 Honorable Rod Souza, Presiding of the Eleventh Judicial District, In and For the County of Flathead, Judge Cause No.