On a Quest for a Better Humanity: Introductory Elements for a Deconstructive Reading of Paul Auster’S the Music of Chance

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pastiche in Paul Auster's the New York Trilogy

qw Advances in Language and Literary Studies ISSN: 2203-4714 Vol. 7 No. 5; October 2016 Australian International Academic Centre, Australia Flourishing Creativity & Literacy Pastiche in Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy Maedeh Zare’e (Corresponding author) Islamic Azad University, Tehran Central Branch, Iran E-mail: [email protected] Razieh Eslamieh Islamic Azad University, Parand Branch, Iran Doi:10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.5p.197 Received: 17/06/2016 URL: http://dx.doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.7n.5p.197 Accepted: 28/08/2016 Abstract This article is a Jamesonian study of Auster’s The New York Trilogy in which one of Fredric Jameson’s notions of postmodernism, pastiche, has been applied on three stories of the novel. This novel is one of Auster’s outstanding postmodern works to which Jameson’s theories of postmodernism, in particular, pastiche can be applicable. Pastiche has been defined by Fredric Jameson as an imitation of a strange style and contrasted to the concept of postmodern parody. This article indicates that theory of pastiche can be applied on both the form and content of three stories of the above mentioned novel. Keywords: Pastiche, Parody, Depthlessness, Historicity 1. Introduction Paul Benjamin Auster (1947) is one of the most influential American postmodern authors, whose works mostly mix realism, experimentation, sociology, absurdism, existentialism and crime fiction. Pastiche, intertextuality, aesthetic dignity and Auster’s own appearance in his works, such as City of Glass (1985), are also some of the features of his works. The search for identity and self-discovery can be found in his works such as The New York Trilogy (2015)1, Moon Palace (1989), The Music of Chance (1990), The Book of Illusions (2002), and The Brooklyn Follies (2005). -

Download Article (PDF)

Advances in Social Science, Education and Humanities Research, volume 289 5th International Conference on Education, Language, Art and Inter-cultural Communication (ICELAIC 2018) A Review of Paul Auster Studies* Long Shi Qingwei Zhu College of Foreign Language College of Foreign Language Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan University Pingdingshan, China Pingdingshan, China Abstract—Paul Benjamin Auster is a famous contemporary Médaille Grand Vermeil de la Ville de Paris in 2010, American writer. His works have won recognition from all IMPAC Award Longlist for Man in the Dark in 2010, over the world. So far, the Critical Community contributes IMPAC Award long list for Invisible in 2011, IMPAC different criticism to his works from varied perspectives in the Award long list for Sunset Park in 2012, NYC Literary West and China. This paper tries to make a review of Paul Honors for Fiction in 2012. Auster studies, pointing out the achievement which has been made and others need to be made. II. A REVIEW OF PAUL AUSTER‘S LITERARY CREATION Keywords—a review; Paul Auster; studies In 1982, Paul Auster published The Invention of Solitude which reflected a literary mind that was to be reckoned with. I. INTRODUCTION It consists of two sections. Portrait of an Invisible Man, the first part, is mainly about his childhood in which there is an Paul Benjamin Auster (born February 3, 1947) is a absence of fatherly love and care. His memory of his growth talented contemporary American writer with great is full of lack of fatherly attention: ―for the first years of my abundance of voluminous works. -

An Analysis Of" City of Glass" by Paul Auster in Terms of Postmodernism

International Journal of Languages’ Education and Teaching Volume 5, Issue 1, April 2017, p. 478-486 Received Reviewed Published Doi Number 17.01.2017 16.02.2017 24.04.2017 10.18298/ijlet.1659 AN ANALYSIS OF CITY OF GLASS BY PAUL AUSTER FROM A POSTMODERNIST PERSPECTIVE1 Mehmet Cem ODACIOĞLU 2 & Chek Kim LOI3 & Fadime ÇOBAN4 ABSTRACT This study analyzes City of Glass, a postmodernist detective novella (or anti-detective) of the New York Trilogy by Paul Auster in terms of postmodernist elements and techniques such as metafiction, parody, intertextuality, irony. In doing so, some information about Auster’s life and the plot of the work are also offered to the reader to make the analysis more concrete. Last but not least, this study is also thought to be useful for students enrolled in English Language and Literary Departments for them to understand the movement of postmodernism. Key Words: City of Class, postmodernist detective fiction, anti-detective, metafiction, parody, irony, intertextuality, pastiche. 1.Short Biography of Paul Auster Paul Auster is an American-Jewish essayist, novelist, translator, poet, screenwriter and memoirist, who was born in Newark, New Jersey on February 3, 1947. Auster lived in a middle class family and spent some of his childhood in the Newark suburbs of South Orange and Maplewood. However, in 1959, his family moved into a large Tudor house. Auster's uncle, Allen Mandelbaum was a translator and left his books for him to read there when he decided to make a journey to Europe. Auster read all of these books which encouraged him to be interested in writing and in literature. -

Critics on White Noise and Moon Palace. on Classification and Genre

Universiteit Utrecht MA – Westerse Literatuur en Cultuur: English Sarah Scholliers (3104591) Critics on White Noise and Moon Palace. On Classification and Genre Hans Bertens Onno Kosters July 2007 Table of Contents Introduction: On Classification 1 CHAPTER ONE: Genre(s) and Critics 4 Contemporary Criticism with Regard to Genre 5 Genres, Auster and DeLillo 9 Two Stories 10 Playing with Genres? 11 Moon Palace 11 White Noise 13 Conclusion 14 CHAPTER TWO: French Influences? 16 Derrida and the Instability of Language 17 Derridean Language in Auster and DeLillo 18 Lacan’s Theory of Language and the Unconscious: in Search of the Sublime 19 Lyotard and the Unpresentable 21 Auster’s and DeLillo’s Sublime: Echoes of Lacan and Lyotard, and Derridean examples 23 Baudrillard’s Simulation 27 A Baudrillardean Auster and DeLillo? 28 Conclusion 30 CHAPTER THREE: American Approaches 32 Postmodern Sublime 32 The Romantic Sublime 32 Space 32 Magic and Dread – The Question of Language 35 Systems Theory 39 Conclusion 42 General Conclusion 43 Bibliography 46 I would like to thank Professor Hans Bertens and Dr. Onno Kosters, my supervisor and co-supervisor respectively, for the careful reading of the first versions of my thesis. INTRODUCTION On Classification Most people have clear ideas about the nature of a work of art. They tend to classify it within a particular category with which they are familiar. They do so, based on their own experience with this (and other) artwork, on critics’ opinion, popular media or hearsay. In general, people approach works of art with an unambiguous view, and they classify a film as a comedy or a book as a thriller. -

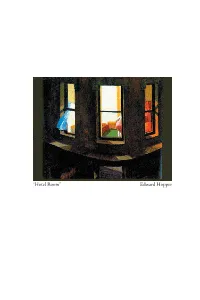

Edward Hopper the Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster

“Hotel Room” Edward Hopper The Light and the Fogg: Edward Hopper and Paul Auster James Peacock University of Edinburgh Auster contributed an extract from Moon Palace to the collection “Edward Hopper and the American Imagination,” and it is clear that Hopper’s images of alienated individuals have had a profound resonance for him. This paper employs two main ideas to compare them. First, a pivotal moment in American literature: the hotel room drama watched by Coverdale in Hawthorne’s Blithedale Romance. Secondly, Aby Warburg’s concept of the “pathos formula” in art, which bypasses the problematic issue of influence, choosing instead to posit sets of inherited cultural memories. It therefore allows discussion of the re-emergence of Hawthorne’s puritan tropes of paranoid specularity and transcendence in the work of Hopper and Auster. I was never able to paint what I set out to paint. (Edward Hopper, quoted in O’Doherty 77) Words are transparent for him, great windows that stand between him and the world, and until now they have never impeded his view, have never even seemed to be there. (G 146) Somewhere in New England in the nineteenth century, a man resumes his “post” (Hawthorne 168) at his hotel room window, there to observe the boarding house opposite. Before long, a “knot of characters” enters one of the rooms, appearing before our observer as if projected onto the physi- cal stage, having been “kept so long upon my mental stage, as actors in a drama.” Longing for “a catastrophe,” some moment of high theatre to fill the epistemological void of his own soul, our voyeur gazes with increasing intensity, fabricating scenarios which, he admits, “might have been alto- gether the result of fancy and prejudice in me.” When, in one of the most compelling and influential moments in all American literature, he is spot- ted by the female protagonist and barred from the scene by the dropping of a curtain, his appetite for narrative resolution remains unsated and he is condemned to brood on his isolation once more. -

“Then Catastrophe Strikes:” Reading Disaster in Paul Auster's Novels and Autobiographies « Then Catastrophe Strikes

Université Paris-Est Northwestern University École doctorale CS – Cultures et Sociétés Weinberg College of Arts & Sciences Laboratoire d’accueil : IMAGER Institut des Comparative Literary Studies Mondes Anglophone, Germanique et Roman, EA 3958 “T HEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES :” READING DISASTER IN PAUL AUSTER ’S NOVELS AND AUTOBIOGRAPHIES « THEN CATASTROPHE STRIKES » : LIRE LE DÉSASTRE DANS L’ŒUVRE ROMANESQUE ET AUTOBIOGRAPHIQUE DE PAUL AUSTER Thèse en cotutelle présentée en vue de l’obtention du grade de Docteur de l’Université de Paris- Est, et de Doctor of Philosophy in Comparative Literature de Northwestern University, par Priyanka DESHMUKH Sous la direction de Mme le Professeur Isabelle ALFANDARY et de M. le Professeur Samuel WEBER Jury Mme Isabelle ALFANDARY , Professeur à l’Université Paris-3 Sorbonne Nouvelle (Directrice de thèse) Mme Sylvie BAUER , Professeur à l’Université Rennes-2 (Rapporteur) Mme Christine FROULA , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) Mme Michal GINSBURG , Professeur à Northwestern University (Examinatrice) M. Jean-Paul ROCCHI , Professeur à l’Université Paris-Est (Examinateur) Mme Sophie VALLAS , Professeur à l’Université d’Aix-Marseille (Rapporteur) M. Samuel WEBER , Professeur à Northwestern University (Co-directeur de thèse) In memory of Matt Acknowledgements I wish I had a more gracious thank-you for: Mme Isabelle Alfandary , who, over the years has allowed me to experience untold academic privileges; whose constant and consistently nurturing presence, intellectual rigor, patience, enthusiasm and invaluable advice are the sine qua non of my growth and, as a consequence, of this work. M. Samuel Weber , whose intellectual generosity, patience and understanding are unparalleled, whose Paris Program in Critical Theory was critical in more ways than one, and without whose participation, the co-tutelle would have been impossible. -

Authorial Turns: Sophie Calle, Paul Auster and the Quest for Identity

Authorial Turns: Sophie Calle, Paul Auster and the Quest for Identity © Anna Khimasia, 2007 Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. Library and Bibliotheque et Archives Canada Archives Canada Published Heritage Direction du Branch Patrimoine de I'edition 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Wellington Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Ottawa ON K1A 0N4 Canada Canada Your file Votre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-36802-2 Our file Notre reference ISBN: 978-0-494-36802-2 NOTICE: AVIS: The author has granted a non L'auteur a accorde une licence non exclusive exclusive license allowing Library permettant a la Bibliotheque et Archives and Archives Canada to reproduce, Canada de reproduire, publier, archiver, publish, archive, preserve, conserve, sauvegarder, conserver, transmettre au public communicate to the public by par telecommunication ou par I'lnternet, preter, telecommunication or on the Internet,distribuer et vendre des theses partout dans loan, distribute and sell theses le monde, a des fins commerciales ou autres, worldwide, for commercial or non sur support microforme, papier, electronique commercial purposes, in microform, et/ou autres formats. paper, electronic and/or any other formats. The author retains copyright L'auteur conserve la propriete du droit d'auteur ownership and moral rights in et des droits moraux qui protege cette these. this thesis. Neither the thesis Ni la these ni des extraits substantiels de nor substantial extracts from it celle-ci ne doivent etre imprimes ou autrement may be printed or otherwise reproduits sans son autorisation. reproduced without the author's permission. In compliance with the Canadian Conformement a la loi canadienne Privacy Act some supporting sur la protection de la vie privee, forms may have been removed quelques formulaires secondaires from this thesis. -

Download the Story of My Typewriter, Paul Auster, Sam Messer, D.A.P

The story of my typewriter, Paul Auster, Sam Messer, D.A.P., 2002, 1891024329, 9781891024320, 63 pages. This is the story of Paul Auster's typewriter. The typewriter is a manual Olympia, more than 25 years old, and has been the agent of transmission for the novels, stories, collaborations, and other writings Auster has produced since the 1970s, a body of work that stands as one of the most varied, creative, and critcally acclaimed in recent American letters. It is also the story of a relationship. A relationship between Auster, his typewriter, and the artist Sam Messer, who, as Auster writes, "has turned an inanimate object into a being with a personality and a presence in the world." This is also a collaboration: Auster's story of his typewriter, and of Messer's welcome, though somewhat unsettling, intervention into that story, illustrated with Messer's muscular, obsessive drawings and paintings of both author and machine. This is, finally, a beautiful object; one that will be irresistible to lovers of Auster's writing, Messer's painting, and fine books in general.. DOWNLOAD http://bit.ly/1bs6nlL Hand to Mouth A Chronicle of Early Failure, Paul Auster, Aug 1, 2003, Biography & Autobiography, 169 pages. From the streets of Manhattan to Paris, a poignant memoir explains a series of ingenious and farfetched attempts to survive on next to no money, showing both the humor and .... Office Collectibles 100 Years of Business Technology, Thomas A. Russo, Jun 1, 2000, , 224 pages. This book presents the most comprehensive collection of antique and collectible office technology that has appeared to date. -

In Search of Self: Explorations of Identity in the Work of Paul Auster

In Search of Self: Explorations of Identity in the Work of Paul Auster THESIS Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS in the Department of English at Rhodes University, Grahamstown, South Africa by Andrew Edward van der Vlies 1998 II ABSTRACT Paul Auster is regarded by some as an important novelist. He has, in a relatively short space of time, produced an intriguing body of work, which has attracted comparatively little critical attention. This study is based on the premise that Auster's art is the record of an entertaining, intelligent and utterly serious engagement with the possibilities of conceiving of the identity of an individual subject in the contemporary, late-twentieth century moment. This study, focussing on Auster's novels, but also considering selected poetry and critical prose, explores the representation of identity in his work. The short Foreword introduces Paul Auster and sketches in outline the concerns of the study. Chapter One explores the manner in which Auster's early (anti-),detective' fiction develops a concern with identity. It is suggested that Squeeze Play, Auster's pseudonymous 'hard-boiled' detective thriller, provided the author with a testing ground for his subsequent appropriation and subversion of the detective genre in The New York Trilogy. Through a close consideration of City of Glass, and an examination of elements in Ghosts, it is shown how the loss of the traditional detective's immunity, and the problematising of strategies which had previously guaranteed him access to interpretive and narrative closure, precipitates a collapse which initiates an interrogation of the nature and construction of ideas about individual identity. -

The Physicality of Writing in Paul Auster's White Spaces and Winter Journal

Angles New Perspectives on the Anglophone World 2 | 2016 New Approaches to the Body The Physicality of Writing in Paul Auster’s White Spaces and Winter Journal François Hugonnier Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/angles/1801 DOI: 10.4000/angles.1801 ISSN: 2274-2042 Publisher Société des Anglicistes de l'Enseignement Supérieur Electronic reference François Hugonnier, « The Physicality of Writing in Paul Auster’s White Spaces and Winter Journal », Angles [Online], 2 | 2016, Online since 01 April 2016, connection on 28 July 2020. URL : http:// journals.openedition.org/angles/1801 ; DOI : https://doi.org/10.4000/angles.1801 This text was automatically generated on 28 July 2020. Angles. New Perspectives on the Anglophone World is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. The Physicality of Writing in Paul Auster’s White Spaces and Winter Journal 1 The Physicality of Writing in Paul Auster’s White Spaces and Winter Journal François Hugonnier “If it really has to be said, it will create its own form.” Paul Auster (1995: 104) 1 White Spaces is a short matrix text written by the poet, novelist and film-maker Paul Auster in the winter of 1978-1979. This meditation on the body, on silence, language and narration is Auster’s immediate reaction to his “epiphanic moment of clarity” (2012: 220, original emphasis) which happened during a dance rehearsal in New York. Initially entitled “Happiness, or a Journey through Space” and “A Dance for Reading Aloud”,1 this hybrid piece of poetic prose was retrospectively considered as “the bridge between writing poetry and writing prose” (1995: 132), and “the bridge to everything you have written in the years since then” (2012: 224). -

The Death of the Other: a Levinasian Reading of Paul Auster's Moon Palace

7KH'HDWKRIWKH2WKHU$/HYLQDVLDQ5HDGLQJRI3DXO $XVWHU V0RRQ3DODFH .DQDH8FKL\DPD MFS Modern Fiction Studies, Volume 54, Number 1, Spring 2008, pp. 115-139 (Article) 3XEOLVKHGE\-RKQV+RSNLQV8QLYHUVLW\3UHVV DOI: 10.1353/mfs.2008.0022 For additional information about this article http://muse.jhu.edu/journals/mfs/summary/v054/54.1uchiyama.html Access provided by University of California, San Diego (18 Feb 2016 08:12 GMT) Uchiyama 115 THE DEATH OF THE OTHER: A LEVINASIAN READING OF f PAUL AUSTER'S MOON PALACE Kanae Uchiyama Introduction: From Identity to Alterity It is widely accepted that Paul Auster's The New York Trilogy echoes the familiar postmodern features—the radical decentering of identity and a skepticism toward ontological language. However, a substantial number of critics, some of whom cite Auster's emerging ethical concerns, agree that it is simplistic to classify Auster's works as postmodernist.1 Postmodern thought, which centers on one of the great motifs of contemporary philosophical thought—the critique or the deconstruction of subjectivity—has often been criticized for its difficultly in dealing with compelling social and political issues without maintaining some notion of the subject. Terry Eagleton, for instance, in After Theory argues that Jacques Derrida's effort to discuss ethics and politics in the realm of deconstruction satisfies neither ethical nor political demands. Derrida asserts there can be no responsibility or ethics without passing through the ordeal of taking infinite respon- sibility for something that one cannot ultimately decide ("Remarks" 86).2 However, Eagleton criticizes Derrida's idea—that justice is an experience of the "undecidable"—for falling outside "all given norms, forms of knowledge and modes of conceptualization" (153). -

Revue LISA/LISA E-Journal, Vol. 18-N°50 | 2020 Money Talks: Language, Work and Authorship from the Music of Chance to Sunset

University of Dundee Money Talks Varvogli, Aliki Published in: Lisa DOI: 10.4000/lisa.11676 Publication date: 2020 Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Link to publication in Discovery Research Portal Citation for published version (APA): Varvogli, A. (2020). Money Talks: Language, Work and Authorship from The Music of Chance to Sunset Park. Lisa, 18(50), 1-17. [8]. https://doi.org/10.4000/lisa.11676 General rights Copyright and moral rights for the publications made accessible in Discovery Research Portal are retained by the authors and/or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. • Users may download and print one copy of any publication from Discovery Research Portal for the purpose of private study or research. • You may not further distribute the material or use it for any profit-making activity or commercial gain. • You may freely distribute the URL identifying the publication in the public portal. Take down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 14. Jun. 2020 Revue LISA/LISA e-journal Littératures, Histoire des Idées, Images, Sociétés du Monde Anglophone – Literature, History of Ideas, Images and Societies of the English-speaking World vol. 18-n°50 | 2020 New Avenues in Paul Auster’s Twenty-First Century Work Money Talks: Language, Work and Authorship from The Music of Chance to Sunset Park L’argent est roi : langage, travail et profession d’auteur de The Music of Chance à Sunset Park Aliki Varvogli Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/lisa/11676 DOI: 10.4000/lisa.11676 ISSN: 1762-6153 Publisher Presses universitaires de Rennes Electronic reference Aliki Varvogli, « Money Talks: Language, Work and Authorship from The Music of Chance to Sunset Park », Revue LISA/LISA e-journal [Online], vol.