SAHS Transactions Volume

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Burton Upon Trent Tales of the Town Ebook

BURTON UPON TRENT TALES OF THE TOWN PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Geoffrey Sowerby | 128 pages | 30 Apr 1998 | The History Press Ltd | 9780752410975 | English | Stroud, United Kingdom Burton Upon Trent Tales of the Town PDF Book The property also benefits from uPVC double glazing. Condition: Good. The 4-a. The wall up the stairs is adorned with pictures of most recent mayors with the current one at the end of the ascending line. On the whole, the town hall had a very classical touch to it, complete with an east end traditional fire-place and a fitted chimney, above which hung the portrait of the first Marquess of Anglesey — Lord Henry Paget. See all our books here, order more than 1 book and get discounted shipping. United Kingdom. Condition: NEW. Newton Fallowell are pleased to be able to offer to the rental market this superb room in this well presented house share in Stapenhill. Administered by The National Trust. Come and see the Staffordshire Regiment Museum tell the story of the bravery, tenacity…. Lichfield Cathedral is a medieval Cathedral with 3 spires set in its own Close and is…. A visit to Tamworth Castle takes you back in time and offers a perfect blend of…. By a strip of land along the riverbank near the present municipal cemetery had been laid out by Edward Cliff, a beerhouse keeper, as a public pleasure ground. Are Beer Festivals a thing of the past, well at least for the foreseeable future? Leave a Reply Cancel reply You must be logged in to post a comment. -

STAFFORDSHIRE. [ KELLY's

312 l'ENN, STAFFORDSHIRE. [ KELLY's Sparrow Mrs. Beckminster house Weller John H. Kelston house, Gold- Harley Wm. (Mrs.), aparts. Oak villa Spencer Mrs. Rose cottage, Penn road thorn hill Hint on Mary, Rose & Ellen (Misstls ), Start Harry, Milton villas Wilcock Robt. Alfred, Goldthorn hill school, Oxford lodge Steadman Joseph, 5 Spring Hill ter Wildman George Charleton,The Cedars Keay Fredk. Wm. farmer, Colway frm Stroud Charles, Penn road Wilke11 Thomas, 3 Milton villas Lowe Samuel, machine proprietor, The Taylor Frederick Davis, Leamcroft Wilkie Miss, Grosvenor house Old farm Taylor Samuel Robt. Worcester lodge Williams Edward, Fern cottage Monk Maryl (Miss), draper, I St. Thorn James, Ashcroft house Williams Thos. Vale ho. Goldthorn hl Phillip's terrace 1'hompson Arthur H. Willow cotta5!.' Witton William, Clifton villas Morris William, shoe maker Thompson James, Apsley house N ash Thomas J oseph, cab proprietor Thompson John, The Uplands COMMERCIAL. Palmer George, commercial traveller, Thompson William, Clifton villa Boucher Mary (Miss), dress maker Elford villas Thurston Chas. Fredk. 2 Church viis Bowdler Joseph, hay & straw dealer Scott Emily (Miss), private school, Tonks Thomas James, Redcliffe Bason Wm. David F.D.H.S. mushroom Clar~nce villas Townsend Mrs. 4 Church road spawn manufactur.. '?, Finchfield Smith Lacey, baker, Ladref house Trezise Mrs. Evelyn cottage Corfield Elizabeth (Miss),dress maker, Spackman Henry Rbt. L.R.C.P.Lond., Underhill Edward M.A. Springfield ho Fair view M.R.C.S.Eng., L.S.A. surgeon & Vaughan Alfred, Leaholm Deam Joseph, decorator, Rookery cot m•3dical officer, Seisdon & \Vom Vaughan William Alfred, Blenheim Evans William, farmer, Finchfield frm bourn •listrict Wakefield Geo. -

Records of the Chicheley Plowdens A.D. 1590-1913; with Four

DUKE UNIVERSITY LIBRARY J ^e \°0 * \ RECORDS OF THE CHICHELEY PLOWDENS, a.d. 1590-1913 /{/w v » Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2018 with funding from hb Duke University Libraries https://archive.org/details/recordsofchichel01plow RECORDS it OF THE Chicheley Plowdens A.D. I59O-I9I3 With Four Alphabetical Indices, Four Pedigree Sheets, and a Portrait of Edmund, the great Elizabethan lawyer BY WALTER F. C. CHICHELEY PLOWDEN (Late Indian Army) PRINTED FOR PRIVATE CIRCULATION HEATH, CRANTON & OUSELEY LTD. FLEET LANE, LONDON, E. C. 1914 ?7 3AV CONTENTS PAGB Introduction ....... i PART I FIRST SERIES The Plowdens of Plowden ..... 6 SECOND SERIES The Chicheley Plowdens . .18 THIRD SERIES The Welsh Plowdens . .41 FOURTH SERIES The American Plowdens ..... 43 PART II CHAPTER I. Sir Edmund Plowden of Wanstead, Kt. (1590-1659) 51 II. Francis the Disinherited and his Descendants, the Plowdens of Bushwood, Maryland, U.S.A. 99 III. Thomas Plowden of Lasham .... 107 IV. Francis of New Albion and his Descendants in Wales . - .112 V. The first two James Plowdens, with some Account OF THE CHICHELEYS AND THE STRANGE WlLL OF Richard Norton of Southwick . .116 VI. The Rev. James Chicheley Plowden, and his Descendants by his Eldest Son, James (4), with an Account of some of his Younger Children . 136 v Contents CHAPTER PAGE VII. Richard and Henry, the Pioneers of the Family in India, and their Children . 151 VIII. The Grandchildren of Richard Chicheley, the H.E.I.C. Director . , . .176 IX. The Grandchildren of Trevor, by his Sons, Trevor (2) and George ..... 186 Conclusion . .191 VI EXPLANATION OF THE SHIELD ON COVER The various arms, twelve in number, in the Chicheley Plowden shield, reading from left to right, are : 1. -

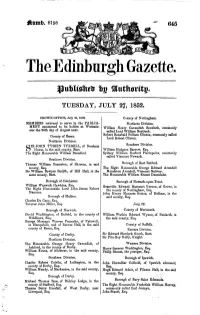

Theedinburgh Gazette. |3Ufcltsltctr Fcg Stutitoritp

Jltttttb. 6198 645 TheEdinburgh Gazette. |3ufcltsltctr fcg Stutitoritp. TUESDAY, JULY 27, 1852, CROWN-OFFICE, July 21, 1852. County of Nottingham. MEMBERS returned to serve in the PARLIA- Northern Division. MENT summoned to be holden at Westmin- William Henry Cavendish Bentinck, commonly ster the 20th day of August next. called Lord William Bentinck. County of Essex. Robert Renebald Pelham Clinton, commonly called Lord Robert Clinton. Northern Division. IR JOHN TYSSEN TYRRELL, of Boreham Southern Division. S House, in the said county, Bart. William Hodgson Barrow, Esq. The Right Honourable William Beresford. Sydney William Herbert Pierrepoint, commonly called Viscount Newark. Southern Division. Thomas William Bramston, of Skreens, in said Borough of East Retford. county, Esq. The Right Honourable George Edward Arundell Sir William Bowyer Srnijth, of Hill Hall, in the Monckton Arundell, Viscount Galway. same county, Bart. The Honourable William Ernest Duncombe. Borough of Colchester. Borough of Newark-upon-Trent. William Warwick Hawkins, Esq. Granville Edward Harcourt Vernon, of Grove, in The Right Honourable Lord John James Robert the county of Nottingham, Esq. Manners. John Henry Manners Sutton, of Kelham, in the Borough of Maldon. said county, Esq. Charles Du Cane, Esq. Tavener John Miller, Esq. July 22. Borough of Harwich. County of Merioneth. David Waddington, of Enfield, in the county of William Watkin Edward Wynne, of Peniarth, in Middlesex, Esq. the said county, Esq. George Montagu Warren Peacocke, of Pylewell, in Hampshire, and of Reeves Hall, in the said County of Suffolk. county of Essex, Esq. Eastern Division. County of Derby. Sir Edward Sherlock Gooch, Bart. Sir Fitz-Roy Kelly, Knight. -

Download Derby Walks

The City Circuit 24 Iron Gate 8 Michael Thomas Bass 16 The Old Bell Hotel 21 The former Boots Building 25 Bonnie Prince Charlie Statue 30 An early 18th century house which was statue This is the last coaching Inn to survive in Derby. Built for the Nottingham based A magnificent life-size statue set up Assembly Rooms/Derby Sales & 1 once the home of horologer, scientist and A statue of Michael Thomas Bass MP for Built in 1680, it was extended with an ornate chemists at the beginning of the high upon a stone plinth. Glossop born Information Centre philosopher, John Whitehurst FRS (1713 – Derby 1847 – 1883 is situated next to the ballroom in 1776 and acquired its timber façade 20th century. The top of the building sculptor, Anthony Stones created the work 1788). In 1855, the roof was removed and the Derby Museum and Library. He funded the in 1929. A meeting was held here in 1884 by displays statues of important which was unveiled in December 1995. The Assembly Rooms complex the Derby Midland Cricket Club. It was during Derby people who have influenced This landmark signifies Bonnie Prince present glass structure substituted to make construction of this fine gothic building. is an award winning architectural a studio for Richard Keene (1825 – 1894) this meeting that the members elected to progress within the city – Florence Charlie’s fateful return to Scotland in design by Casson and Conder Derby’s pioneer Victorian photographer. form their own football team – the evolution of Nightingale, John Lombe (co-founder 1745. He arrived in Derby on 4 December built in 1977. -

Demo Version

DEMO VERSION This file was created with the DEMO VERSION of CAD-KAS PDFs 2 One. This is the reason why this file contains this page. The order the full version please visit our website under http://www.cadkas.com ACCOU NTANT Subject Caption Print No. Year Artist Foster, Mr. Harry Seymour An Undersheriff 1783 1891 SPY AMBASSADORS FROM ENGLAND 1459 Doyle, Mr. Percy William,C. B. Diplomacy 1873 Unsigned Durand, The Right Hon. Sir Henry Mortimer, Washington Post 1543 1904 SPY G.C.M.G., K.C.S.I., K.C.I.E. Elliot, The Right Hon. Sir Henry George, G.C.B. Ambassador To The 6-203 1877 SPY Porte Herbert, Sir Michael Henry, P.C., K.C.M.G. Washington 901 1903 SPY Hudson, Sir James, G.C.B. Ill-Used B-142 1874 APE Last~elles,Sir Frank Cavendish, P.C., G.C.B., G.C.M.G. Berlin B-285 1902 SPY Lyons, Lord Dip3macy 1739 1878 APE MacDonald, Sir Claude Maxwell, K.C.B. Tokio B-86 1901 SPY Malet, Sir Edward Baldwin, K.C.B. Justice! Justice! B-289 1884 SPY O’Conor, The Rt. Hon. Sir Nicholas. G.C.M.G. Diplomacy B-348 1907 SPY Russell, The Right Hon. Lord Odo William Odo 1410 1877 SPY Dwand. He,,~y Leopold, G.C.B. ‘~ Thornton, H.E. The Right Hon. Sir Edward, G.C.B. A Safe Ambassador 6-47 1886 APE Wellesley, Colonel the Hon. Frederick Arthur Promotion by Merit 1574 1878 APE Wyke, Sir Charles Lennox, K.C.B., G.C.M.G. -

Hoteliers and Hotels: Case Studies the Growth and Development of U.K. Hotel Companies 1945 - 1989

HOTELIERS AND HOTELS: CASE STUDIES THE GROWTH AND DEVELOPMENT OF U.K. HOTEL COMPANIES 1945 - 1989 DONALD A STEWART Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the University of Glasgow Faculty of Social Sciences Department of Economic History October 1994 (c) Donald A Stewart (1994) ProQuest Number: 13818405 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818405 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 {GLASGOW { u n i v e r s i t y \ ti m r TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE LIST OF TABLES iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS vii ABSTRACT ix Introduction 1 Chapter 1 The Development of the UK 5 Hotel Industry Chapter 2 The Independent Sector 69 Introduction 1. The Goring Hotel, London 2. The Lygon Arms, Broadway, Worcestershire 3. The Metropole, Llandrindod Wells 4. The Open Arms, Dirleton Conclusions on Independent Sector Chapter 3 Hotel Groups Geared To The UK Market 156 Introduction 1. Mount Charlotte Investments Pic 2. Norfolk Capital Group Pic 3. Centre Hotels, Comfort Hotels, Friendly Hotels 4. -

Station Street & Borough Road Burton Upon Trent

Station Street & Borough Road Burton upon Trent Conservation Area Appraisal July 2015 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION.................................................. 2 2 PLANNING POLICY CONTEXT ............................. 4 3 DEFINITION OF SPECIAL INTEREST ..................... 6 4 LOCATION & SETTING ........................................ 7 5 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT ............................ 10 6 TRADITIONAL SHOPFRONTS ............................ 17 7 TOWNSCAPE ASSESSMENT .............................. 18 8 LANDSCAPE & PUBLIC REALM ASSESSMENT ... 30 9 HERITAGE ASSETS ............................................ 31 10 CAPACITY TO ACCOMODATE CHANGE ............ 36 11 MANAGEMENT RECOMMENDATION .............. 37 12 DESIGN GUIDANCE .......................................... 38 Document: 5895 FIN Station Street & APPENDIX I REFERENCES & SOURCES ...................... 39 IBI Taylor Young Borough Road Conservation Area Appraisal APPENDIX II HISTORIC ENVIRONMENT RECORD ..... 40 Compiled by: LW Chadsworth House FIGURES Reviewed by: AC Wilmslow Road Date: July 2015 Handforth 1 HERITAGE ASSETS .................... ......................... 3 Cheshire SK9 3HP 2 CONSERVATION AREA CONTEXT ....................... 9 Tel: 01625 542200 Fax: 01625 542250 3 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT............................15 E mail: [email protected] 4 -8 HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT ............................ 16 9 TOWNSCAPE ANALYSIS .................................... 29 Page 1 Station Street & Borough Road Conservation Area Appraisal 1 INTRODUCTION 1.6 The appraisal -

Vebraalto.Com

THE COACH HOUSE RANGEMORE HALL DUNSTALL ROAD RANGEMORE DE13 9RH ACCOMMODATION An impressive three-bedroom residence with breathtaking gardens located on the grounds of the prestigious Rangemore Hall. Ground floor: reception hall. First floor: open plan drawing room, dining room, kitchen/breakfast room, and bedroom one with en-suite bathroom. Second floor: bedroom two and three both with en-suite shower room, open plan mezzanine forming study/entertainment room. Outside: private gated communal driveway, communal grounds with landscaped gardens, woodland, and lake, private landscaped gardens, three allocated parking spaces. Approximate gross internal floor area 2,242 square feet (208 square metres). EPC rating Exempt. Situation flagstone tiled drawing room/sitting room and dining area. A beautiful slate Rangemore Hall is located in a beautiful stretch of Staffordshire countryside fire surround (created from original slate taken from Rangemore Hall close to the renowned St George's Park, an extensive sports centre serving scullery) houses a log burner with exposed brick decor. Large sash picture the FA but also having prestigious hotels, bar and restaurant, sports and windows provide views of the impressive gardens and grounds beyond to the leisure facilities. The nearby village of Barton under Needwood offers every front and Georgian windows are to the rear. day amenities with shops, post office, chemist, library, GP surgery, churches, and excellent schools. There is ample space for a dining area, making this an ideal space for The location allows for easy travel to the facilities and amenities of Lichfield receiving and entertaining family and friends. The bespoke designed kitchen and Burton upon Trent. -

Church Bells, 9

December5, 1884.] Church Bells, 9 SUBSTITUTION OF VOLUNTARY OFFERINGS FOR LEGAL DUES. BELLS AND BELL - RINGING. Paper read by the Chancellor of Lichfield at the Diocesan Conference. It may seem rather curious to discuss now the question whether Church The late Mr. G. Stockham. fees should be voluntary, inasmuch as all fees are in their inception On Monday, the 1 st inst., ten members of the St. James’s Society rang a voluntary, but being' paid for many years by different persons, have peal of 5129 Grandsire Caters, with the bells half muffled, in 3 hrg. id mins. eventually become customary, and when the custom can be proved are J. B. Haworth, 1; J. Mansfield, 2 ; C. F. Winny, 3 ; W. Weatherstone, 4 ; recoverable by legal process. If, however, they are to become purely E. Horrex, 5; E. French, 6 ; J. Martin Routh, Esq., 7; J. M. Hayes (con voluntary, unless a fresh custom should be established, there seems to be ductor), 8 ; G. Banks, 9 ; E. Albone, 10. It was rung at St. Clement Danes, danger that they might disappear altogether like Easter offerings, or Strand, London, in memory of Mr. Stockham, who had been a member of partially as fees at Archdeacons’ Visitations, or possibly become unduly the above Society and steeple-keeper of the above church for about fifty years. He died 011 the 15th of November, and was buried at Highgate Cemetery on large by mere force of habit. tlie 22nd, The legatees of Mr. Stockham will—under the superintendence It happens often enough that A regulates his payment by the amount of Mr. -

White's 1857 Directory of Derbyshire

HISTORY OF THE BOROUGH OF DERBY. DERBY, a municipal and parliamentary borough and market town, is the capital of the county to which it gives name, in the hundred of Morleston and Litchurch, 52° 50′ north latitude, and 1° 27′ west longitude, from Greenwich; 132 miles by railway and 126 miles N.W. by the old road from London, 13 miles S.E. from Ashbourn, 25 miles S. from Bakewell, 24 miles S. by W. from Chesterfield, 10½ miles N.E. from Burton on Trent, 15½ miles W. by S. from Nottingham, and 29 miles N.W. from Leicester. It is an ancient town and formerly had a castle. The streets of the old part are crooked and narrow, but the new streets are well built and many of the modern houses are spacious and handsome. The Markeaton brook, running through the town, issues into the Derwent at the cast extremity; it is crossed by seven stone bridges, erected by a general subscription, with one of wood, and an elegant bridge of three elliptical arches over the Derwent; which with the silk mills, the wears, and broad expanse of the river, forms a handsome entrance to the town from Nottingham. The town is lighted with gas, and the streets are regularly paved, and considerable improvements and additions have, during the last 10 years, been made to the buildings of this busy and flourishing borough; which is plentifully supplied with water from the new works erected in 1850, at Little Eaton, at a cost of £40,000. The vale of the Derwent on the south presents an extensive level district, and the walks in the vicinity of the town are very pleasant. -

MBAS July 2003 Newsletter

Warren Becker and Bill Coleman present a iii|||ÇÇÇàààtttzzzxxx UUUxxxxxxÜÜÜ gggtttáááààà|||ÇÇÇzzz January 22, 2005 Bass Ratcliff Ale - 1869 hard for a few. For some who could not support themselves and their Bass Kings Ale - 1902 families the Workhouse could be an unhappy last resort. The brewery owners, although mostly rich men, were often liberal minded & con- H&G Simonds Ltd. Coronation Ale - 1911 tributed to the community, serving as MPs and donating large sums to Bass Prince Ale - 1929 civic & community projects. Both the very rich and the very poor Worthington Burton Strong Ale - 1930 played their part in making Burton upon Trent a lively and successful Charrington's Prince's Brew - 1932 town of late Victorian Britain. Ind Coope & Allsopp Ltd. Jubilee Ale - 1935 Courage Founder's Ale - 1937 Fremlins Ltd. Christmas Ale - 1950 Truman's No.1 Burton Barley Wine - 1950 ER Coronation Ale - 1953 Bass Jubilee Strong Ale - 1977 Home Brewery Jubilee Strong Ale - 1977 Wadsworth Queens Ale - 1977 Cameron's Harelepool Crown Ale - 1978 Ansells Strong Ale - Silver Jubilee - 1978 St. Austell Princess Barleywine - 1979 Greene King Audit Barleywine - 1980 Bass & Co Ltd, 137 High Street, Burton upon Trent, Staffs These bottles represent some of the earliest commemorative bottles, in this case marking the visits to the brewery of the King and the Prince of Wales in the years noted. The Bass Commemorative Ales http://www.royal-ales.com/ Over the years brewed several Commemorative Ales have been specially brewed to mark an important occasion such as a royal visit, a brewing cen- tenary or to honor retiring staff.