Net Loss Population Settlement Patterns and Maintenance of Rural Health Status: a Case Study in Atlantic Canada

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Where to Go for Help – a Resource Guide for Nova Scotia

WHERE TO GO ? FOR HELP A RESOURCE GUIDE FOR NOVA SCOTIA WHERE TO GO FOR HELP A Resource Guide for Nova Scotia v 3.0 August 2018 EAST COAST PRISON JUSTICE SOCIETY Provincial Divisions Contents are divided into the following sections: Colchester – East Hants – Cape Breton Cumberland Valley – Yarmouth Antigonish – Pictou – Halifax Guysborough South Shore Contents General Phone Lines - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 Crisis Lines - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 9 HALIFAX Community Supports & Child Care Centres - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 11 Food Banks / Soup Kitchens / Clothing / Furniture - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 17 Resources For Youth - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 20 Mental, Sexual And Physical Health - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 22 Legal Support - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 28 Housing Information - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 31 Shelters / Places To Stay - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 33 Financial Assistance - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 35 Finding Work - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 36 Education Support - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 39 Supportive People In The Community – Hrm - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 40 Employers who do not require a criminal record check - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - 41 COLCHESTER – EAST HANTS – CUMBERLAND Community Supports And Child Care Centres -

EXPLORER Official Visitors Guide

eFREE 2021 Official Visitors Guide Annapolis Rxploroyal & AreaerFREE Special Edition U BEYO D OQW TITEK A Dialongue of Place & D’iversity Page 2, explorer, 2021 Official Visitors Guide Come in and browse our wonderful assortment of Mens and Ladies apparel. Peruse our wide The unique Fort Anne Heritage Tapestry, designed by Kiyoko Sago, was stitched by over 100 volunteers. selection of local and best sellers books. Fort Anne Tapestry Annapolis Royal Kentville 2 hrs. from Halifax Fort Anne’s Heritage Tapestry How Do I Get To Annapolis Royal? Exit 22 depicts 4 centuries of history in Annapolis Holly and Henry Halifax three million delicate needlepoint Royal Bainton's stitches out of 95 colours of wool. It Tannery measures about 18’ in width and 8’ Outlet 213 St George Street, Annapolis Royal, NS Yarmouth in height and was a labor of love 19025322070 www.baintons.ca over 4 years in the making. It is a Digby work of immense proportions, but Halifax Annapolis Royal is a community Yarmouth with an epic story to relate. NOVA SCOTIA Planning a Visit During COVID-19 ANNAPOLIS ROYAL IS CONVENIENTLY LOCATED Folks are looking forward to Fundy Rose Ferry in Digby 35 Minutes travelling around Nova Scotia and Halifax International Airport 120 Minutes the Maritimes. “Historic, Scenic, Kejimkujik National Park & NHS 45 Minutes Fun” Annapolis Royal makes the Phone: 9025322043, Fax: 9025327443 perfect Staycation destination. Explorer Guide on Facebook is a www.annapolisroyal.com Convenience Plus helpful resource. Despite COVID19, the area is ready to welcome visitors Gasoline & Ice in a safe and friendly environment. -

March 2020 Newsletter.Pub

Municipality of Colchester NOTICE The March 2020 Municipality of Colchester NEWSLETTER (Volume 25 Issue 1) was printed prior to widespread cancellations, closures, and changes to services necessary to prevent the spread of COVID-19. This insert provides updated information as of March 24, 2020. All Municipality of Colchester buildings are closed to the public until further notice. All recreation programming is cancelled until further notice. Municipal essential services will continue during building closures. These include solid waste collection, sewer and water maintenance, snow removal, critical road repairs, building inspection, and bill processing. All Colchester Solid Waste Facilities are closed to the public until further notice. Licensed haulers can still access the facilities. Curbside collection will continue as regularly scheduled. Call the Solid Waste Helpline for additional information: 902-895-4777. The application deadline for the Low-Income Municipal Tax Assistance Program has been extended to May 29, 2020. The property Tax Sale previously scheduled for May 5, 2020 is postponed. Once a new date has been set it will be posted on www.colchester.ca and the Colchester Facebook page. The Municipality is closely following advice from the Province of Nova Scotia as it is continually updated on their COVID-19 website: www.novascotia.ca/coronavirus. Please visit this website for reliable health and safety information. Other NEWSLETTER Updates: Unfortunately, the Colchester Legion Pipes & Drums have had to cancel their April to celebrate the 75th anniversary of the Liberation of the Netherlands. Their hope is that events are rescheduled. The Colchester-Truro Volunteer Award Ceremony that was to take place on April 20, 2020 is postponed. -

Philadelphia Township Grant (Parrsboro, NS

Nova Scotia Archives Finding Aid - Philadelphia Township Grant (Parrsboro, N.S.) collection (Accession 2011-030) Generated by Access to Memory (AtoM) 2.3.1 Printed: July 18, 2017 Language of description: English Nova Scotia Archives 6016 University Ave. Halifax Nova Scotia B3H 1W4 Telephone: (902) 424-6060 Fax: (902) 424-0628 Email: [email protected] http://archives.novascotia.ca/ https://memoryns.ca/index.php/philadelphia-township-grant-parrsboro-n-s-collection Philadelphia Township Grant (Parrsboro, N.S.) collection Table of contents Summary information ...................................................................................................................................... 3 Administrative history / Biographical sketch .................................................................................................. 3 Scope and content ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Notes ................................................................................................................................................................ 3 Physical condition ........................................................................................................................................... 3 Series descriptions ........................................................................................................................................... 4 - Page 2 - Accession 2011-030 Philadelphia Township Grant -

The Whidden Family of Truro, Colchester County, Nova Scotia

Whidden Family Register Report The Whidden Family of Truro, Colchester County, Nova Scotia Prepared by H. Douglas Goff (son of Doris Whidden, #136ii) 7748 Wellington Rd. 22 Guelph, ON Canada N1H 6J2 email goff.doug at gmail.com www.gofffamilyhistory.ca Updated Dec. 23, 2020 Index, pg. 77 There are at least three compilations of Whidden family genealogy, listed below, and it is not my intention here to diminish their work or importance, just to place online a sketch of the Whidden family of Nova Scotia to help people who are doing internet searches to find their ancestors and to make readers aware of these more thorough and detailed sources. 1. The Whidden Family of Nova Scotia, 1973, by Miss Helen H. Whidden and her nephew Phillip Whidden Barlow. Private Printing. 2. The Whidden Family of Colchester, by Jane Currie Wile. https://colchesterhistoreum.ca/book-mart/ 3. Whidden, Paul David and Raymond Marvin Whidden. 2007. Whidden: NH, NS and beyond, 1662-2002. A Family Odyssey. 2 Volumes. Private Printing. Sources for this genealogy include the above three, although not all the detail has been copied, plus: 1. Miller, Thomas. 1873. Historical and Genealogical Record of the first settlers of Colchester County. Halifax, NS , A. and W. MacKinlay, Publ. Facsimilie Edition by Mika Studio, Belleville, Ont., 1972. 2. www.novascotiagenealogy.com - Nova Scotia Historical Vital Statistics (NSHVS) – b,m,d data 3. http://www.bac-lac.gc.ca/eng/census/Pages/census.aspx - Nova Scotia census data 4. www.familysearch.org - United States b,m,d and census data, publically accessible. -

Fort Beausejour National Historic Park Aulac, New Brunswick Canada

Fort Beausejour National Historic Park Aulac, New Brunswick Canada Issued under the authority of the HONOURABLE ARTHUR LAING, P.C., M.P., B.S.A. Minister of Indian Affairs and Northern Development Original Earthen Bastion of French Period Fort Beausejour National Historic Park Aulac, New Brunswick At the middle of the 18th century the dividing line between French and British influence in Acadia lay along the Missaguash River, one of the four rivers that drain the southern slope of the Isthmus of Chignecto. In 1710 New England militiamen and British regulars had captured the French Port Royal, thus in one engagement effecting the conquest of the Nova Scotia main- land. The Treaty of Utrecht, concluded three years later, formally transferred Acadia to Great Britain. But what was Acadia? The British hopefully believed parts of what is now New Brunswick were included. The French, confident that they would soon win back the Nova Scotia mainland, could not consider such a broad definition of the geographical limits of Acadia. They were determined to hold as much ground as they could. Time seemed to be in their favor. Against the weak and ill-disciplined garrison at Annapolis Royal and the few detachments occupying isolated posts in the peninsula, the French could send Indian raiding parties. While the British struggled against the harassments of the Indians, the population of Acadia—over whelmingly French—could be provoked to at least passive resistance against their alien conquerors. French power preserved at the Fortress of Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island and at the settlements of New France along the St. -

(MEDC) AGENDA September 12, 2017 at 6:00 Pm Members: Chai

Town of Annapolis Royal Marketing and Economic Development Committee September 12, 2017 Town of Annapolis Royal Marketing and Economic Development Committee (MEDC) AGENDA September 12, 2017 at 6:00 pm Members: Chair Councillor Owen Elliot, Vice-Chair Amy Barr, Councillor Holly Sanford, Mayor MacDonald, Diana Lewis, Samantha Myhre and Benjamin Boysen. Administration: CAO Greg Barr and Recording Secretary Sandi Millett-Campbell. 1. CALL TO ORDER 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA 3. APPROVAL OF THE MINUTES – July 11, 2017 (Tab 1) 4. PUBLIC INPUT 5. PRESENTATIONS i. Twinning Committee Update – Christine Igot (Tab 2) 6. BUSINESS ARISING i. Workplan – Population Strategies (Tab 3) ii. Natal Day Wrap Up – Councillor Sanford iii. Tall Ships Wrap Up – Sandi Millett-Campbell iv. Community Identity Signage v. Town Crier Expanded Distribution 7. NEW BUSINESS i. Ghost Town ii. Doers & Dreams 2018 (Tab 4) iii. MEDC/ABoT Fall Luncheon – Proposed date October 11, 2017 8. TWINNING COMMITTEE MINUTES – (Tab 5) 9. CORRESPONDENCE FOR INFORMATION 10. ADJOURNMENT 11. Next Meeting: MEDC – October 10, 2017 at 6:00 pm Town of Annapolis Royal Marketing and Economic Development Committee July 11, 2017 Town of Annapolis Royal Marketing and Economic Development Committee (MEDC) AGENDA July 11, 2017 at 6:00 pm Members: Chair Councillor Owen Elliot, Vice-Chair Amy Barr, Councillor Holly Sanford, Samantha Myhre and Benjamin Boysen. Administration: CAO Greg Barr and Recording Secretary Courtney Campbell. Regrets: Diana Lewis, Mayor Bill MacDonald 1. CALL TO ORDER: Chair Elliot called the meeting to order at 6:02pm. 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA: MOTION #MEDC-2017-JUL-11-1 It was moved by Councillor Sanford, seconded by Amy Barr, to approve the July 11, 2017 agenda as presented. -

Nova Scotia Inland Water Boundaries Item River, Stream Or Brook

SCHEDULE II 1. (Subsection 2(1)) Nova Scotia inland water boundaries Item River, Stream or Brook Boundary or Reference Point Annapolis County 1. Annapolis River The highway bridge on Queen Street in Bridgetown. 2. Moose River The Highway 1 bridge. Antigonish County 3. Monastery Brook The Highway 104 bridge. 4. Pomquet River The CN Railway bridge. 5. Rights River The CN Railway bridge east of Antigonish. 6. South River The Highway 104 bridge. 7. Tracadie River The Highway 104 bridge. 8. West River The CN Railway bridge east of Antigonish. Cape Breton County 9. Catalone River The highway bridge at Catalone. 10. Fifes Brook (Aconi Brook) The highway bridge at Mill Pond. 11. Gerratt Brook (Gerards Brook) The highway bridge at Victoria Bridge. 12. Mira River The Highway 1 bridge. 13. Six Mile Brook (Lorraine The first bridge upstream from Big Lorraine Harbour. Brook) 14. Sydney River The Sysco Dam at Sydney River. Colchester County 15. Bass River The highway bridge at Bass River. 16. Chiganois River The Highway 2 bridge. 17. Debert River The confluence of the Folly and Debert Rivers. 18. Economy River The highway bridge at Economy. 19. Folly River The confluence of the Debert and Folly Rivers. 20. French River The Highway 6 bridge. 21. Great Village River The aboiteau at the dyke. 22. North River The confluence of the Salmon and North Rivers. 23. Portapique River The highway bridge at Portapique. 24. Salmon River The confluence of the North and Salmon Rivers. 25. Stewiacke River The highway bridge at Stewiacke. 26. Waughs River The Highway 6 bridge. -

R E P O R T S 112 Structure of the Minas Passage, Bay of Fundy: A

Reports 112 Structure of the Minas Passage, Bay of Fundy: A Preliminary Report* DONALD J. P. SWIFT Duke University, Durham, N. C. FRANK L. JAGODITS Huntec Limited, Toronto, Ont. BERNARD L. MANISTRE Lockwood Survey Corporation Limited, Toronto, Ont. NORMAN R. PATERSON Huntec Limited, Toronto, Ont. Introduction From July, 1965 to March, 1966, a joint geological-geophysical study of the Minas Passage, Bay of Fundy, was undertaken by Huntec Limited of Toronto for the Atlantic Development Board of Canada. The purpose of the project was to test the feasibility of a tidal power station in the Passage. This paper presents a portion of the study, namely the structure of the geologically critical Minas Passage area and its bearing on regional structure. The Bay of Fundy is a funnel-shaped body of water lying between Nova Scotia and New Brunswick (Fig. 1). Fundy proper is 144 kilometers long, 100 kilometers wide at the base, and averages 75 meters in depth. The northeast end bifurcates into northeast-trending Chignecto Bay, and the east-trending Minas Basin. Three distinct bodies of water are included within the latter; the Minas Basin proper; the Minas Channel, separated from the basin by the great curved peninsula of Cape Blomidon-Cape Split; and the Minas Passage, connecting the Channel and the Basin (Fig. 2). ^Manuscript received 12 January, 1968. Reports 113 -V. N - ~M ' , , , - I . , I - I Figure 2 - The Minas Passage with Cape Split in the background. Stratigraphy Three well-defined bedrock sequences occur in the Minas Passage area. The Cobequid Complex is a lower Paleozoic metamorphic and igneous complex comprising the upraised Cobequid Fault Block (Fig. -

Cultural Assets of Nova Scotia African Nova Scotian Tourism Guide 2 Come Visit the Birthplace of Canada’S Black Community

Cultural Assets of NovA scotiA African Nova scotian tourism Guide 2 Come visit the birthplace of Canada’s Black community. Situated on the east coast of this beautiful country, Nova Scotia is home to approximately 20,000 residents of African descent. Our presence in this province traces back to the 1600s, and we were recorded as being present in the provincial capital during its founding in 1749. Come walk the lands that were settled by African Americans who came to the Maritimes—as enslaved labour for the New England Planters in the 1760s, Black Loyalists between 1782 and 1784, Jamaican Maroons who were exiled from their home lands in 1796, Black refugees of the War of 1812, and Caribbean immigrants to Cape Breton in the 1890s. The descendants of these groups are recognized as the indigenous African Nova Scotian population. We came to this land as enslaved and free persons: labourers, sailors, farmers, merchants, skilled craftspersons, weavers, coopers, basket-makers, and more. We brought with us the remnants of our cultural identities as we put down roots in our new home and over time, we forged the two together and created our own unique cultural identity. Today, some 300 years later, there are festivals and gatherings throughout the year that acknowledge and celebrate the vibrant, rich African Nova Scotian culture. We will always be here, remembering and honouring the past, living in the present, and looking towards the future. 1 table of contents Halifax Metro region 6 SoutH SHore and YarMoutH & acadian SHoreS regionS 20 BaY of fundY & annapoliS ValleY region 29 nortHuMBerland SHore region 40 eaStern SHore region 46 cape Breton iSland region 50 See page 64 for detailed map. -

They Planted Well: New England Planters in Maritime Canada

They Planted Well: New England Planters in Maritime Canada. PLACES Acadia University, Wolfville, Nova Scotia, 9, 10, 12 Amherst Township, Nova Scotia, 124 Amherst, Nova Scotia, 38, 39, 304, 316 Andover, Maryland 65 Annapolis River, Nova Scotia, 22 Annapolis Township, Nova Scotia, 23, 122-123 Annapolis Valley, Nova Scotia, 10, 14-15, 107, 178 Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, 20, 24-26, 28-29, 155, 258 Annapolis Gut, Nova Scotia, 43 Annapolis Basin, Nova Scotia, 25 Annapolis-Royal (Port Royal-Annapolis), 36, 46, 103, 244, 251, 298 Atwell House, King's County, Nova Scotia, 253, 258-259 Aulac River, New Brunswick, 38 Avon River, Nova Scotia, 21, 27 Baie Verte, Fort, (Fort Lawrence) New Brunswick, 38 Barrington Township, Nova Scotia, 124, 168, 299, 315, Beaubassin, New Brunswick (Cumberland Basin), 36 Beausejour, Fort, (Fort Cumberland) New Brunswick, 17, 22, 36-37, 45, 154, 264, 277, 281 Beaver River, Nova Scotia, 197 Bedford Basin, Nova Scotia, 100 Belleisle, Annapolis County, Nova Scotia, 313 Biggs House, Gaspreau, Nova Scotia, 244-245 Blomidon, Cape, Nova Scotia, 21, 27 Boston, Massachusetts, 18, 30-31, 50, 66, 69, 76, 78, 81-82, 84, 86, 89, 99, 121, 141, 172, 176, 215, 265 Boudreau's Bank, (Starr's Point) Nova Scotia, 27 Bridgetown, Nova Scotia, 196, 316 Buckram (Ship), 48 Bucks Harbor, Maine, 174 Burton, New Brunswick, 33 Calkin House, Kings County, 250, 252, 259 Camphill (Rout), 43-45, 48, 52 Canning, Nova Scotia, 236, 240 Canso, Nova Scotia, 23 Cape Breton, Nova Scotia, 40, 114, 119, 134, 138, 140, 143-144 2 Cape Cod-Style House, 223 -

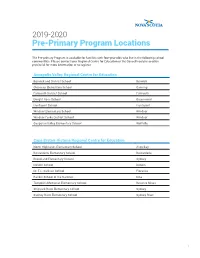

2019-2020 Pre-Primary Program Locations

2019-2020 Pre-Primary Program Locations The Pre-primary Program is available for families with four-year-olds who live in the following school communities. Please contact your Regional Centre for Education or the Conseil scolaire acadien provincial for more information or to register. Annapolis Valley Regional Centre for Education Berwick and District School Berwick Glooscap Elementary School Canning Falmouth District School Falmouth Dwight Ross School Greenwood Hantsport School Hantsport Windsor Elementary School Windsor Windsor Forks District School Windsor Gasperau Valley Elementary School Wolfville Cape Breton-Victoria Regional Centre for Education North Highlands Elementary School Aspy Bay Boularderie Elementary School Boularderie Brookland Elementary School Sydney Donkin School Donkin Dr. T.L. Sullivan School Florence Rankin School of the Narrows Iona Tompkins Memorial Elementary School Reserve Mines Shipyard River Elementary School Sydney Sydney River Elementary School Sydney River 1 Chignecto-Central Regional Centre for Education West Colchester Consolidated School Bass River Cumberland North Academy Brookdale Great Village Elementary School Great Village Uniacke District School Mount Uniacke A.G. Baillie Memorial School New Glasgow Cobequid District Elementary School Noel Parrsboro Regional Elementary School Parrsboro Salt Springs Elementary School Pictou West Pictou Consolidated School Pictou Scotsburn Elementary School Scotsburn Tatamagouche Elementary School Tatamagouche Halifax Regional Centre for Education Sunnyside Elementary School Bedford Alderney Elementary School Dartmouth Caldwell Road Elementary School Dartmouth Hawthorn Elementary School Dartmouth John MacNeil Elementary School Dartmouth Mount Edward Elementary School Dartmouth Robert K. Turner Elementary School Dartmouth Tallahassee Community School Eastern Passage Oldfield Consolidated School Enfield Burton Ettinger Elementary School Halifax Duc d’Anville Elementary School Halifax Elizabeth Sutherland Halifax LeMarchant-St.