Lady Smith Woodward's Biography

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Forgotten Crocodile from the Kirtland Formation, San Juan Basin, New

posed that the narial cavities of Para- Wima1l- saurolophuswere vocal resonating chambers' Goniopholiskirtlandicus Apparently included with this material shippedto Wiman was a partial skull that lromthe Wiman describedas a new speciesof croc- forgottencrocodile odile, Goniopholis kirtlandicus. Wiman publisheda descriptionof G. kirtlandicusin Basin, 1932in the Bulletin of the GeologicalInstitute KirtlandFormation, San Juan of IJppsala. Notice of this specieshas not appearedin any Americanpublication. Klilin NewMexico (1955)presented a descriptionand illustration of the speciesin French, but essentially repeatedWiman (1932). byDonald L. Wolberg, Vertebrate Paleontologist, NewMexico Bureau of lVlinesand Mineral Resources, Socorro, NIM Localityinformation for Crocodilian bone, armor, and teeth are Goni o p holi s kir t landicus common in Late Cretaceous and Early Ter- The skeletalmaterial referred to Gonio- tiary deposits of the San Juan Basin and pholis kirtlandicus includesmost of the right elsewhere.In the Fruitland and Kirtland For- side of a skull, a squamosalfragment, and a mations of the San Juan Basin, Late Creta- portion of dorsal plate. The referral of the ceous crocodiles were important carnivores of dorsalplate probably represents an interpreta- the reconstructed stream and stream-bank tion of the proximity of the material when community (Wolberg, 1980). In the Kirtland found. Figs. I and 2, taken from Wiman Formation, a mesosuchian crocodile, Gonio- (1932),illustrate this material. pholis kirtlandicus, discovered by Charles H. Wiman(1932, p. 181)recorded the follow- Sternbergin the early 1920'sand not described ing locality data, provided by Sternberg: until 1932 by Carl Wiman, has been all but of Crocodile.Kirtland shalesa 100feet ignored since its description and referral. "Skull below the Ojo Alamo Sandstonein the blue Specimensreferred to other crocodilian genera cley. -

Brains and Intelligence

BRAINS AND INTELLIGENCE The EQ or Encephalization Quotient is a simple way of measuring an animal's intelligence. EQ is the ratio of the brain weight of the animal to the brain weight of a "typical" animal of the same body weight. Assuming that smarter animals have larger brains to body ratios than less intelligent ones, this helps determine the relative intelligence of extinct animals. In general, warm-blooded animals (like mammals) have a higher EQ than cold-blooded ones (like reptiles and fish). Birds and mammals have brains that are about 10 times bigger than those of bony fish, amphibians, and reptiles of the same body size. The Least Intelligent Dinosaurs: The primitive dinosaurs belonging to the group sauropodomorpha (which included Massospondylus, Riojasaurus, and others) were among the least intelligent of the dinosaurs, with an EQ of about 0.05 (Hopson, 1980). Smartest Dinosaurs: The Troodontids (like Troödon) were probably the smartest dinosaurs, followed by the dromaeosaurid dinosaurs (the "raptors," which included Dromeosaurus, Velociraptor, Deinonychus, and others) had the highest EQ among the dinosaurs, about 5.8 (Hopson, 1980). The Encephalization Quotient was developed by the psychologist Harry J. Jerison in the 1970's. J. A. Hopson (a paleontologist from the University of Chicago) did further development of the EQ concept using brain casts of many dinosaurs. Hopson found that theropods (especially Troodontids) had higher EQ's than plant-eating dinosaurs. The lowest EQ's belonged to sauropods, ankylosaurs, and stegosaurids. A SECOND BRAIN? It used to be thought that the large sauropods (like Brachiosaurus and Apatosaurus) and the ornithischian Stegosaurus had a second brain. -

Sandra Carreras*

2019. Revista Encuentros Latinoamericanos, segunda época. Vol. III, Nº 1, enero/junio ISSN1688-437X DOI---------------------------------------- De los viajes de exploración a la experimentación genética. El papel de los científicos alemanes en la conformación de saberes transnacionales en Argentina, Chile y Uruguay (siglo XIX a comienzos del XX) From the exploratory routes to the genetic experimentation. The rol of german scientists in the conformation of transnational knowledge in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay (19th century to beginning of 20th) Sandra Carreras * Ibero-Amerikanisches Institut Preußischer Kulturbesitz. [email protected] Recibido: 29.01.18 Aceptado: 29.05.19 Sandra Carreras. De los viajes de exploración a la experimentación genética. 117-141 Resumen Este artículo trata la actuación e inserción de científicos de origen alemán en Argentina, Chile y Uruguay entre principios del siglo XIX y comienzos del XX, distinguiendo tres momentos. El primero corresponde a los viajes de exploración de Friedrich Sellow y Hermann Burmeister. La segunda fase fue protagonizada por tres naturalistas que dirigieron los museos nacionales de cada país: Rudolph AmandusPhilippi, Hermann Burmeister y Carl Berg. La tercera etapa se caracteriza por la contratación de cuerpos de profesores de origen alemán organizar la Academia de Ciencias de Córdoba, el Instituto Pedagógico de Santiago, el Instituto Nacional del Profesorado Secundario en Buenos Aires y la Facultad de Agronomía en Montevideo. Además de actuar en su ámbito local, los científicos alemanes radicados en los tres países mantuvieron una activa red de relaciones entre sí y con sus colegas en Alemania, actuando como intermediadores entre distintos ámbitos. Palabras clave: Mediadores culturales; Científicos alemanes; Viajes de exploración; Instituciones científicas; Redes transnacionales; Ciencias Naturales Abstract In this article I analyze the action and engagement of German-speaking scientists in Argentina, Chile and Uruguay between the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th centuries. -

The Dates of the Discovery of the First Peking Man Fossil Teeth

The Dates of the Discovery of the First Peking Man Fossil Teeth Qian WANG,LiSUN, and Jan Ove R. EBBESTAD ABSTRACT Four teeth of Peking Man from Zhoukoudian, excavated by Otto Zdansky in 1921 and 1923 and currently housed in the Museum of Evolution at Uppsala University, are among the most treasured finds in palaeoanthropology, not only because of their scientific value but also for their important historical and cultural significance. It is generally acknowledged that the first fossil evidence of Peking Man was two teeth unearthed by Zdansky during his excavations at Zhoukoudian in 1921 and 1923. However, the exact dates and details of their collection and identification have been documented inconsistently in the literature. We reexamine this matter and find that, due to incompleteness and ambiguity of early documentation of the discovery of the first Peking Man teeth, the facts surrounding their collection and identification remain uncertain. Had Zdansky documented and revealed his findings on the earliest occasion, the early history of Zhoukoudian and discoveries of first Peking Man fossils would have been more precisely known and the development of the field of palaeoanthropology in early twentieth century China would have been different. KEYWORDS: Peking Man, Zhoukoudian, tooth, Uppsala University. INTRODUCTION FOUR FOSSIL TEETH IDENTIFIED AS COMING FROM PEKING MAN were excavated by palaeontologist Otto Zdansky in 1921 and 1923 from Zhoukoudian deposits. They have been housed in the Museum of Evolution at Uppsala University in Sweden ever since. These four teeth are among the most treasured finds in palaeoanthropology, not only because of their scientific value but also for their historical and cultural significance. -

Wren's Nest at 60

SCIENTISTVOLUME 27 NO 7 ◆ August 2017 ◆ WWW.GEOLSOC.ORG.UK/GEOSCIENTIST GEOThe Fellowship Magazine of the Geological Society of London UK / Overseas where sold to individuals: £3.95 ] [REVIEWS SPECIAL! Wren’s Nest at 60 Celebrating the World’s first National Nature Reserve ONLINE SPECIAL FELLOWS’ ROOM HUTTON’S DEBT The long road from Society reoccupies Did Hutton crib his famous ‘disposal’ to ‘recovery’ a valuable amenity line from Browne? GEOSCIENTIST CONTENTS 17 24 10 25 REGULARS IN THIS ISSUE... 05 Welcome Ted Nield says true ‘scientific outreach’ is integral, not a strap-on prosthetic. 06 Society News What your Society is doing at home and abroad, in London and the regions. 09 Soapbox Mike Leeder discusses Hutton’s possible debt to Sir Thomas Browne ON THE COVER: 16 Calendar Society activities this month 10 CATCHING THE DUDLEY BUG 20 Letters New The state of Geophysics MSc courses in the Andrew Harrison looks back on the UK; The new CPD system (continued). 61st year of the World’s first NNR 22 Books and arts Thirteen new books reviewed by Dawn Brooks, Malcolm Hart, Gordon Neighbour, Calymene blumenbachii or ‘Dudley Bug’. James Montgomery, Wendy Cawthorne, Jeremy Joseph, David Nowell, Martin Brook, Alan Golding, Mark Griffin, Courtesy, Dudley Museum Services Hugh Torrens, Nina Morgan and Amy-Jo Miles 24 People Geoscientists in the news and on the move 27 Obituary Robin Temple Hazell 1927 - 2017 RECOVERY V. DISPOSAL William Braham 1957 -2016 NLINE Chris Berryman on applying new guidance 27 Obituary affecting re-use of waste soil materials. -

La Entomología En La Argentina Hasta La Creación De La Sociedad Entomológica Argentina

Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina ISSN: 0373-5680 ISSN: 1851-7471 [email protected] Sociedad Entomológica Argentina Argentina La entomología en la Argentina hasta la creación de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina. Un panorama histórico DE ASÚA, Miguel La entomología en la Argentina hasta la creación de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina. Un panorama histórico Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina, vol. 80, núm. 1, 2021 Sociedad Entomológica Argentina, Argentina Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=322065128001 PDF generado a partir de XML-JATS4R por Redalyc Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto Foro La entomología en la Argentina hasta la creación de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina. Un panorama histórico e Entomology in Argentina until the creation of the Sociedad Entomológica Argentina. A historical survey Miguel DE ASÚA [email protected] Centro de Investigaciones Filosóficas, Academia Nacional de Ciencias de Buenos Aires (CONICET)-Instituto de Investigación e Ingeniería Ambiental (3IA), Universidad Nacional de San Martín., Argentina Resumen: Este trabajo es una mirada histórica al crecimiento de los estudios entomológicos en Argentina, desde el s. XVIII hasta 1925, año de creación de la Sociedad Entomológica Argentina. En este panorama se distinguen tres períodos: (a) Revista de la Sociedad Entomológica la investigación sobre insectos en el Río de la Plata durante la época colonial y de la Argentina, vol. 80, núm. 1, 2021 Independencia, y -

Histoire(S) De Collecfions

Colligo Histoire(s) de Collections Colligo 3 (3) Hors-série n°2 2020 PALÉONTOLOGIE How to build a palaeontological collection: expeditions, excavations, exchanges. Paleontological collections in the making – an introduction to the special issue Irina PODGORNY, Éric BUFFETAUT & Maria Margaret LOPES P. 3-5 La guerre, la paix et la querelle. Les sociétés A Frenchman in Patagonia: the palaeontological paléontologiques d'Auvergne sous la Seconde expeditions of André Tournouër (1898-1903) Restauration Irina PODGORNY Éric BUFFETAUT P. 7-31 P. 67-80 Two South American palaeontological collections Paul Carié, Mauritian naturalist and forgotten in the Natural History Museum of Denmark collector of dodo bones Kasper Lykke HANSEN Delphine ANGST & Éric BUFFETAUT P. 33-44 P. 81-88 Cataloguing the Fauna of Deep Time: Researchers following the Glossopteris trail: social Paleontological Collections in Brazil in the context of the debate surrounding the continental Beginning of the 20th Century drift theory in Argentina in the early 20th century Maria Margaret LOPES Mariana F. WALIGORA P. 45-56 P. 89-103 The South American Mammal collection at the Natural history collecting by the Navy in French Museo Geologico Giovanni Capellini (Bologna, Indochina Italy) Virginia VANNI et al. Marie-Béatrice FOREL P. 57-66 P. 105-126 1 SOMMAIRE Paleontological collections in the making – an introduction to the special issue Collections paléontologiques en développement – introduction au numéro spécial Irina PODGORNY, Éric BUFFETAUT & Maria Margaret LOPES P. 3-5 La guerre, la paix et la querelle. Les sociétés paléontologiques d'Auvergne sous la Seconde Restauration War, Peace, and Quarrels: The paleontological Societies in Auvergne during the Second Bourbon Restoration Irina PODGORNY P. -

Catalog of the Types of Curculionoidea (Insecta, Coleoptera) Deposited at the Museo Argentino De Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia”, Buenos Aires

Rev. Mus. Argentino Cienc. Nat., n.s. 15(2): 209-280, 2013 ISSN 1514-5158 (impresa) ISSN 1853-0400 (en línea) Catalog of the types of Curculionoidea (Insecta, Coleoptera) deposited at the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia”, Buenos Aires Axel O. BACHMANN 1 & Analía A. LANTERI 2 1Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales, División Entomología, Buenos Aires C1405DJR. Universidad de Buenos Aires, Facultad de Ciencias Exactas y Naturales, Buenos Aires C1428EHA, e-mail: [email protected]. uba.ar. 2 Museo de La Plata, División Entomología, Paseo del Bosque s/n, La Plata, B1900FWA, Argentina, e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The type specimens of Curculionoidea (Apionidae, Brentidae, Anhribidae, Curculionidae, Platypodidae, and Scolytidae) from the Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales (MACN), corresponding to all current categories, are herein catalogued. A total of 344 specific and subspecific names are alphabetically recorded, for their original binomina or trinomina, and spellings. Later combinations and synonyms are mentioned, as well as the informa- tion of all the labels associated to the specimens. In order to assist future research, three further lists are added: 1. specimens deemed to be deposited at MACN but not found in the collection; 2. specimens labeled as types of species which descriptions have probably never been published (non available names); and 3. specimens of dubi- ous type status, because the information on the labels does not agree with that of the original publication. Key words: Type specimens, Curculionoidea, Coleoptera, Insecta. Resumen: Catálogo de los tipos de Curculionoidea (Insecta, Coleoptera) depositados en el Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia”, Buenos Aires. -

Portraits from Our Past

M1634 History & Heritage 2016.indd 1 15/07/2016 10:32 Medics, Mechanics and Manchester Charting the history of the University Joseph Jordan’s Pine Street Marsden Street Manchester Mechanics’ School of Anatomy Medical School Medical School Institution (1814) (1824) (1829) (1824) Royal School of Chatham Street Owens Medicine and Surgery Medical School College (1836) (1850) (1851) Victoria University (1880) Victoria University of Manchester Technical School Manchester (1883) (1903) Manchester Municipal College of Technology (1918) Manchester College of Science and Technology (1956) University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology (1966) e University of Manchester (2004) M1634 History & Heritage 2016.indd 2 15/07/2016 10:32 Contents Roots of the University 2 The University of Manchester coat of arms 8 Historic buildings of the University 10 Manchester pioneers 24 Nobel laureates 30 About University History and Heritage 34 History and heritage map 36 The city of Manchester helped shape the modern world. For over two centuries, industry, business and science have been central to its development. The University of Manchester, from its origins in workers’ education, medical schools and Owens College, has been a major part of that history. he University was the first and most Original plans for eminent of the civic universities, the Christie Library T furthering the frontiers of knowledge but included a bridge also contributing to the well-being of its region. linking it to the The many Nobel Prize winners in the sciences and John Owens Building. economics who have worked or studied here are complemented by outstanding achievements in the arts, social sciences, medicine, engineering, computing and radio astronomy. -

Catalogue of the Papers of Professor Sir William Boyd Dawkins in the John Rylands University Library of Manchester

CATALOGUE OF THE PAPERS OF PROFESSOR SIR WILLIAM BOYD DAWKINS IN THE JOHN RYLANDS UNIVERSITY LIBRARY OF MANCHESTER GEOFFREY TWEEDALE DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY, UNIVERSITY OF SHEFFIELD AND TIMOTHY PROCTER HISTORY GRADUAND, CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF OXFORD INTRODUCTION* According to a recent study, 'the history of the rise of geology over the past 200 years can, through British eyes at least, be seen to comprise two different but closely interconnected strands'. 1 The first relates more to Natural History and looks toward the scientific or 'pure' front. The second connects with mining and the search for raw materials and is slanted towards the industrial or 'applied' horizon. In contemplating these two strands of geological history it is interesting to note that it is the scientific branch of geology that has traditionally brought fame and fortune. In the nineteenth century it was the Victorian 'gentleman' geologist who enjoyed the greatest respect and power. Some became national figures, as their work on rock strata, geological surveys and minerals was found useful in the drive for 'imperial' expansion. These were the men who filled museums with their geological specimens, engaged in the most prominent controversies of the day, wrote books and articles and left papers - and naturally won prestige, influence and honours. 2 These protagonists of scientific geology have also been the chief interest of historians. This is despite the fact that the growth of * \\'e are grateful to Jack Morrell (Bradford University > and Hugh Torrens (Keele University) for providing references for this paper. 1 U.S. Torrens, 'Hawking history: a vital future for geology's past', Modem Geology, 13 (1988), 83-93. -

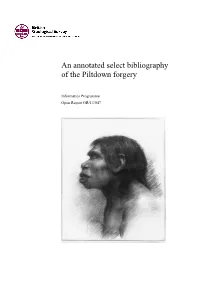

An Annotated Select Bibliography of the Piltdown Forgery

An annotated select bibliography of the Piltdown forgery Informatics Programme Open Report OR/13/047 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY INFORMATICS PROGRAMME OPEN REPORT OR/13/47 An annotated select bibliography of the Piltdown forgery Compiled by David G. Bate Keywords Bibliography; Piltdown Man; Eoanthropus dawsoni; Sussex. Map Sheet 319, 1:50 000 scale, Lewes Front cover Hypothetical construction of the head of Piltdown Man, Illustrated London News, 28 December 1912. Bibliographical reference BATE, D. G. 2014. An annotated select bibliography of the Piltdown forgery. British Geological Survey Open Report, OR/13/47, iv,129 pp. Copyright in materials derived from the British Geological Survey’s work is owned by the Natural Environment Research Council (NERC) and/or the authority that commissioned the work. You may not copy or adapt this publication without first obtaining permission. Contact the BGS Intellectual Property Rights Section, British Geological Survey, Keyworth, e-mail [email protected]. You may quote extracts of a reasonable length without prior permission, provided a full acknowledgement is given of the source of the extract. © NERC 2014. All rights reserved Keyworth, Nottingham British Geological Survey 2014 BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY The full range of our publications is available from BGS shops at British Geological Survey offices Nottingham, Edinburgh, London and Cardiff (Welsh publications only) see contact details below or shop online at www. geologyshop.com BGS Central Enquiries Desk Tel 0115 936 3143 Fax 0115 936 3276 The London Information Office also maintains a reference collection of BGS publications, including maps, for consultation. email [email protected] We publish an annual catalogue of our maps and other publications; this catalogue is available online or from any of the Environmental Science Centre, Keyworth, Nottingham BGS shops. -

Meteorite Iron in Egyptian Artefacts

SCIENTISTu u GEO VOLUME 24 NO 3 APRIL 2014 WWW.GEOLSOC.ORG.UK/GEOSCIENTIST The Fellowship Magazine of the Geological Society of London UK / Overseas where sold to individuals: £3.95 READ GEOLSOC BLOG! [geolsoc.wordpress.com] Iron from the sky Meteorite iron in Egyptian artefacts FISH MERCHANT WOMEN GEOLOGISTS BUMS ON SEATS Sir Arthur Smith Woodward, Tales of everyday sexism If universities think fieldwork king of the NHM fishes - an Online Special sells geology, they’re mistaken GEOSCIENTIST CONTENTS 06 22 10 16 FEATURES IN THIS ISSUE... 16 King of the fishes Sir Arthur Smith Woodward should be remembered for more than being caught by the Piltdown Hoax, says Mike Smith REGULARS 05 Welcome Ted Nield has a feeling that some eternal verities have become - unsellable 06 Society news What your Society is doing at home and abroad, in London and the regions 09 Soapbox Jonathan Paul says universities need to beef up their industrial links to attract students ON THE COVER: 21 Letters Geoscientist’s Editor in Chief sets the record straight 10 Iron from the sky 22 Books and arts Four new books reviewed by Catherine Meteoritics and Egyptology, two very different Kenny, Mark Griffin, John Milsom and Jason Harvey disciplines, recently collided in the laboratory, 25 People Geoscientists in the news and on the move write Diane Johnson and Joyce Tyldesley 26 Obituary Duncan George Murchison 1928-2013 27 Calendar Society activities this month ONLINE SPECIALS Tales of a woman geologist Susan Treagus recalls her experiences in the male-dominated groves of