March 1949 Full Issue

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Alumni News University Publications

La Salle University La Salle University Digital Commons La Salle College Alumni News University Publications 3-1949 Alumni News: March 1949 La Salle University Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/alumni_news Recommended Citation La Salle University, "Alumni News: March 1949" (1949). La Salle College Alumni News. 2. http://digitalcommons.lasalle.edu/alumni_news/2 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at La Salle University Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in La Salle College Alumni News by an authorized administrator of La Salle University Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. LUNCH BANQUET CLUB MAY 16th APR. 4 t h ALUMNI NEWS BROADWOOD VOL. III MARCH, 1949 No. 2 President Plans Banner A lumni Y ear Levy Appoints Chairmen of Open House: Medal, Banquet and Breakfast Events FIRST AFFAIR IN MAY Following a full Board meeting of Class representatives, held at LaSalle College on February 28th, Oscar F. Levy ’38, Alumni P resi dent, formally announced the cal endar of Alumni social activities for the coming year. The Open House, an annual sports affair, will be held soon after Easter, with James J. McKeegan ’40, as Chair m an. Nationally famous columnist and television star Ed Sullivan receives the LaSalle The Annual Alumni Banquet will COLLEGIAN Public Service in Journalism Award from editor Walter J. Brough, as Brother G. Paul, President of LaSalle, looks on. Sullivan was invited to par be held on May 16th, Founders Day. ticipate in LaSalle’s observance of Catholic Press Month by virtue of his work in Chairman Al Whalen '20, is work combating juvenile delinquency, and for his efforts on behalf of Catholic and other ing out the details for the location charities in New York. -

Secretaries of Defense

Secretaries of Defense 1947 - 2021 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Contents Historical Origins of the Secretary of Defense . iii Secretaries of Defense . 1 Secretaries of Defense Demographics . 28 History of the Positional Colors for the Office of the Secretary of Defense . 29 “The Secretary of Defense’s primary role is to ensure the national security . [and] it is one of the more difficult jobs anywhere in the world. He has to be a mini-Secretary of State, a procurement expert, a congressional relations expert. He has to understand the budget process. And he should have some operational knowledge.” Frank C. Carlucci former Secretary of Defense Prepared by Dr. Shannon E. Mohan, Historian Dr. Erin R. Mahan, Chief Historian Secretaries of Defense i Historical Origins of the Secretary of Defense The 1947 National Security Act (P.L. 80-253) created the position of Secretary of Defense with authority to establish general policies and programs for the National Military Establishment. Under the law, the Secretary of Defense served as the principal assistant to the President in all matters relating to national security. James V. Forrestal is sworn in as the first Secretary of Defense, September 1947. (OSD Historical Office) The 1949 National Security Act Amendments (P.L. 81- 216) redefined the Secretary of Defense’s role as the President’s principal assistant in all matters relating to the Department of Defense and gave him full direction, authority, and control over the Department. Under the 1947 law and the 1949 Amendments, the Secretary was appointed from civilian life provided he had not been on active duty as a commissioned officer within ten years of his nomination. -

Yale Stuart Papers

YALE STUART COLLECTION 2 manuscript boxes Processed: January 1966 Accession Number 159 By: WWP The papers of Yale Stuart were deposited with the Labor History Archives in May 1965 by Mr. Stuart, who at one time served as president of the Detroit J o i n t Board, U n i t ed P u b l i c Workers - CIO. The collection covers the period from 1945 to 1949. The papers are copies of o r i g i n a l s retained by Mr. Stuart. They document the activities of the United Public Workers and of Mr. Stuart as representatives of the employees of the C i t y of Detroit. The correspondence, arranged chronologically, is a f i l e of outgoing letters, in the main, to o f f i c i a l s of the Detroit government. The remainder of the material is also arranged chronologically. It covers such areas as wage increases, right of municipal employes to enter into collective bargaining, representation elections and loyality oaths. YALE STUART COLLECTION Box 1, Correspondence, May, November and December 1945 September-December 1946 January-May 1947 June-December 1947 January-March 1948 April-September 1948 October-December 1948 January 1949 February-March 1949 April-June 1949 July-December 1949 Press Releases, December 1946 - April 1949 Resolutions, 1947-1949 Circulars, late 1940's Box 2, Circulars, late 1940's (3 folders) By-laws Detroit Joint Board, UPW-CIO Proposals re: Sanitation Division of DPW, 1945-1949 Proposal to Common Council for Maintenance of Take Home Pay, December 13, 1945 Right of Municipal Employees to Enter into Collective Bargaining, 1946 DPW Representation Election, May 21, 1946 Statement on House B i l l 418 Citizens Committee re: Ci ty Employees' Weges, March 1946 Statement on School Lunchroom Wages and Hot Lunch Program, March 21, 1947 UPW Proposals to Common Council re: Budget, March 1947 Statement before Common Council, July 10, 1947 Statement to Board of Education re: Budget, November 18, 1947 Proposed Study of Cit y and County Welfare Administration, November 25 and Dec. -

Convention on International Civil Aviation Signed at Chicago on 7 December 1944

CONVENTION ON INTERNATIONAL CIVIL AVIATION SIGNED AT CHICAGO ON 7 DECEMBER 1944 Entry into force: The Convention entered into force on 4 April 1947. Status: 193 parties. This list is based on information received from the depositary, the Government of the United States of America Date of deposit of instrument of ratification or notification of State adherence (A) Afghanistan 4 April 1947 Albania 28 March 1991 (A) Algeria 7 May 1963 (A) Andorra 26 January 2001 (A) Angola 11 March 1977 (A) Antigua and Barbuda 10 November 1981 (A) Argentina 4 June 1946 (A) Armenia 18 June 1992 (A) Australia 1 March 1947 Austria 27 August 1948 (A) Azerbaijan 9 October 1992 (A) Bahamas 27 May 1975 (A) Bahrain 20 August 1971 (A) Bangladesh 22 December 1972 (A) Barbados 21 March 1967 (A) Belarus 4 June 1993 (A) Belgium 5 May 1947 Belize 7 December 1990 (A) Benin 29 May 1961 (A) Bhutan 17 May 1989 (A) Bolivia (Plurinational State of) 4 April 1947 Bosnia and Herzegovina 13 January 1993 (A) Botswana 28 December 1978 (A) Brazil 8 July 1946 Brunei Darussalam 4 December 1984 (A) Bulgaria 8 June 1967 (A) Burkina Faso 21 March 1962 (A) Burundi 19 January 1968 (A) Cabo Verde 19 August 1976 (A) Cambodia 16 January 1956 (A) Cameroon 15 January 1960 (A) Canada 13 February 1946 Central African Republic 28 June 1961 (A) Chad 3 July 1962 (A) Chile 11 March 1947 China (1) 20 February 1946 Colombia 31 October 1947 Comoros 15 January 1985 (A) Congo 26 April 1962 (A) Cook Islands 20 August 1986 (A) Costa Rica 1 May 1958 Côte d’Ivoire 31 October 1960 (A) Croatia 9 April 1992 (A) -

Scanned Using Fujitsu 6670 Scanner and Scandall Pro Ver 1.7

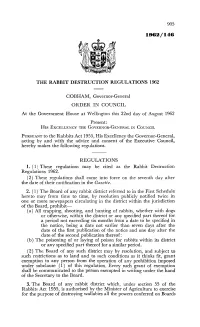

905 1962/146 THE RABBIT DESTRUCTION REGULATIONS 1962 COBHAM, Governor-General ORDER IN COUNCIL At the Government House at Wellington this 22nd day of August 1962 Present: HIS EXCELLENCY THE GOVERNOR-GENERAL IN COUNCIL PURSUANT to the Rabbits Act 1955, His Excellency the Governor-General, acting by and with the advice and consent of the Executive Council, hereby makes the following regulations. REGULATIONS 1. (1) These regulations may be cited as the Rabbit Destruction Regulations 1962. (2) These regulations shall come into force on the seventh day after the date of their notification in the Gazette. 2. (1) The Board of any rabbit district referred to in the First Schedule hereto may from time to time, by resolution publicly notified twice in one or more newspapers circulating in the district within the jurisdiction of the Board, prohibit- (a) All trapping, shooting, and hunting of rabbits, whether with dogs or otherwise, within the district or any specified part thereof for a period not exceeding six months from a date to be specified in the notice, being a date not earlier than seven days after the date of the first publication of the notice and one day after the date of the second publication thereof: (b) The poisoning of or laying of poison for rabbits within its district or any specified part thereof for a similar period. (2) The Board of any such district may by resolution, and subject to such restrictions as to land and to such conditions as it thinks fit, grant exemption to any person from the operation of any prohibition imposed under subclause (1) of this regulation. -

March 1949) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 3-1-1949 Volume 67, Number 03 (March 1949) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, and the Music Performance Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 67, Number 03 (March 1949)." , (1949). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/164 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. aenor *,v CJbe (Celebrated JOHN CHURCH COMPANY SONG COLLECTIONS SONG CLASSICS heavy paper covers and Bound substantially in Edited by Horatio Parker engraved plates on quality printed from beautifully Tenor, Bass necessity to the singer Soprano, Alto, these volumes are a Four Volumes: - paper, established artist, this vo well-balanced repertoire. For either the budding or desiring a and comprehensive group- ume offers a convenient choice of songs, Mr. accepted classics. In his ing of value E. Krehbiel ‘classic’ > ts fue FAMOUS SONGS Edited by H. Parker considered the work literature, or ^art, of the first “a standard work of Volumes: Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass foremost composers, from Four class” Notable songs by eminent the nucleus of a reper- available collections by an Bach through Wolf, supply One of the finest presented both m a former critic for best songs. -

NATO in the Beholder's Eye: Soviet Perceptions and Policies, 1949-1956

WOODROW WILSON INTERNATIONAL CENTER FOR SCHOLARS Christian Ostermann, Lee H. Hamilton, NATO in the Beholder’s Eye: Director Director Soviet Perceptions and Policies, 1949-56 BOARD OF ADVISORY TRUSTEES: COMMITTEE: Vojtech Mastny Joseph A. Cari, Jr., William Taubman Chairman (Amherst College) Steven Alan Bennett, Working Paper No. 35 Chairman Vice Chairman PUBLIC MEMBERS Michael Beschloss (Historian, Author) The Secretary of State Colin Powell; The Librarian of James H. Billington Congress (Librarian of Congress) James H. Billington; The Archivist of the United States Warren I. Cohen John W. Carlin; (University of Maryland- The Chairman of the Baltimore) National Endowment for the Humanities Bruce Cole; John Lewis Gaddis The Secretary of the (Yale University) Smithsonian Institution Lawrence M. Small; The Secretary of James Hershberg Education (The George Washington Roderick R. Paige; University) The Secretary of Health & Human Services Tommy G. Thompson; Samuel F. Wells, Jr. (Woodrow Wilson PRIVATE MEMBERS Washington, D.C. Center) Carol Cartwright, John H. Foster, March 2002 Sharon Wolchik Jean L. Hennessey, (The George Washington Daniel L. Lamaute, University) Doris O. Mausui, Thomas R. Reedy, Nancy M. Zirkin COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT THE COLD WAR INTERNATIONAL HISTORY PROJECT WORKING PAPER SERIES CHRISTIAN F. OSTERMANN, Series Editor This paper is one of a series of Working Papers published by the Cold War International History Project of the Woodrow Wilson International Center for Scholars in Washington, D.C. Established in 1991 by a grant from the John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation, the Cold War International History Project (CWIHP) disseminates new information and perspectives on the history of the Cold War as it emerges from previously inaccessible sources on “the other side” of the post-World War II superpower rivalry. -

Decade 1940 to 1949

Decade 1940 to 1949 Development 1940 U.S. Census puts Harlingen's population at 13,306. It is characterized as 62% American, 36% Latin-American and 2% Negro. 9/40 Mayor Hugh Ramsey makes a definitive proposal to the War Department to establish an Army Air Field at Harlingen. On 6/17/40 he had reported to the C of C that land suitable for a base had been pinpointed and that the city was attempting to acquire it. 12/17/40 The Hug-the Coast Highway opens. It runs from Orange, TX (just across the Louisiana state line) to Brownsville and in parts is predecessor to US Highway 77. 1941 Mayor Ramsey and Harlingen City Commissioners J.L. Head, Guy Leggett, Bouldin C. Mothershead, W.E. Gaines, W.C. Anderson, and Arthur Dabney together with U.S. Senators Tom Connally and Morris Shepherd go to Washington to present the city's plans to the War Department. 3/41 Army Air Corps officials in Washington announce approval of Harlingen Air Training Base and in May this is confirmed. Later authority to proceed comes with the approval of a $3.8 million appropriation. 6/30/41 A contract is let for Morgan and Zachary, El Paso and Laredo, builders to start the military airfield construction. 7/41 Harlingen Army Airfield is established for the training of gunnery students. By 1945 more than 48,000 gunners have utilized the facility, now the Valley International Airport. With its palm-lined streets and flowering shrubs it was known as the "showplace of the air force." 11/28/41 Col. -

Special Libraries, March 1949 Special Libraries Association

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1949 Special Libraries, 1940s 3-1-1949 Special Libraries, March 1949 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1949 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, March 1949" (1949). Special Libraries, 1949. Book 3. http://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1949/3 This Magazine is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1940s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1949 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Special Libraries VOLUME40 . Established 1910 . NUMBER3 CONTENTS FOR MARCH 1949 Some Remarks on Subject Headings . C. D. GULL Patent Searching . C. D. STORES Microcards and the Special Library . MARJORIEC. KEENLEYSIDE Translating as a Business Profession . CHARLESA. MEYER SLA Fortieth Annual Convention . KATHLEENB. STEBBINS New Institutional Members . SLA Chapter Highlights . SLA Publications in Print . Comments from Members . Events and Publications Announcements . Indexed in Industrial Arts Index, Public &airs Information Service, and Library Literature ALMA CLARVOEMITCHILL KATHLEENBROWN STEBBINS Editor Advertising Manager The articles which appear in SPECIAL LIBRARIESexpress the views of the authors, and do not necessarily represent the opinion or the policy of the editorial staff and publisher. SLA OFFICERS, 1948-49 ROSE L. VORMELKER,President Business Information Bureau, Cleveland Public Library, Cleveland 14, Ohio MRS. RUTH I5 HOOKER,First Vice-president and President-Elect Naval Research Laboratory, Washington 20, D. C. MELVINJ. -

19Th Annual Report of the Bank for International Settlements

BANK FOR INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENTS NINETEENTH ANNUAL REPORT 1st APRIL 1948 — 31st MARCH 1949 BASLE 13th June 1949 BANK FOR INTERNATIONAL SETTLEMENTS, BASLE NINETEENTH ANNUAL REPORT ERRATA: Page 17: in the table, a footnote reference (2) should be added to the heading "Direct aid"; in the column "Countries", instead of: Germany (2), read: Germany (3). Page 60: in the table, instead of: Raw materials and imported products, read: Raw materials and semi-finished goods. Page 66: table - "United Kingdom: Gross national product", under "Resources", instead of: Provision for depreciation and maintenance of buildings, read: Provision for depreciation and maintenance paragraph 2, line 2, instead of: . personal consumption rose only by about £320 million and government consumption is found to have declined by £165 million ... read: . personal consumption rose only by about £540 million and government consumption is found to have declined by £155 million ... paragraph 2, line 5, instead of: Economic Survey for 1948 . read: Economic Survey for 1949 • . Page 107: table - "Wage increases", add to "France", as footnote (1), i1) Figures for 1947. table - "Amount of wheat covered by the Wheat Agreement", United States, in millions of bushels, instead of: 68, read: 168. Page 108: line 4, instead of: ... delivered as follows by the exporting countries, read: . delivered by the exporting countries as shown in the table on the preceding page. Page no: in the table - "Terms of trade", the heading should be corrected as follows : Average Values of Terms of Year Imports U.K.Exports Page 124: paragraph 5, line 1, instead of: DM 3.33 = $ 1, read: RM 3.33 = $ 1. -

Western Aust A

[1097] OF WESTERN AUST A (Published by Authority at 3.30 p.m.) (REGISTERED AT THE GENERAL POST OFFICE, PERTH, FOR TRANSMISSION BY POST AS A NEWSPAPER) PERTH: TUESDAY, 27th APRIL Crown Law Department, Perth, 14th April, 1965. THE undermentioned regulations made under the provisions of the Milk Act, 1946-1964, and amended from time to time prior to the 1st March, 1965, are reprinted pursuant to the Reprinting of Regulations Act, 1954, by authority of the Minister for Justice. R. C. GREEN, Under Secretary for Law. MILK ACT, 1946-1964. MIL ACT REGULATIONS. (Published in sets of regulations in the Government Gazette as follows:- On the 21st February, 1947, regulations cited as the Milk Act, 1946, Regulations No. 1; On the 18th July, 1947, regulations cited as the Milk Act, 1946, Regulations No. 2; On the 12th December, 1947, regulations cited as the Milk Act, 1946, Regulations No. 3; On the 15th October, 1948, regulations cited as the Milk Act, 1946- 1947, Regulations No. 4; On the 18th March, 1949, regulations cited as the Milk Act, 1946- 1948, Regulations No. 5; On the 3rd June, 1949, regulations cited as the Milk Act, 1946-1948, Regulations No. 6; On the 22nd July, 1949, regulations cited as the Milk Act, 1946-1948, Regulations No. 7; On the 17th March, 1950, regulations cited as the Milk Act, 1946- 1948, Regulations No. 8; and On the 2nd February, 1962, regulations cited as the Milk Act, 1946- 1960, Regulations No. 9; and incorporating the amendments published in the Government Gazette on the 28th November, 1947, the 18th March, 1949, -

Employers, Workers, and Wages, April-June 1949

all instances they represent a “bar- Employers, Workers, from April-June 1948 and January- gain” to the annuitant. These arbi- March 1949, respectively. The total trary factors were undoubtedly and Wages, April-June number of workers employed in cov- introduced for ease in administration, ered industries, estimated at 38.8 mil- but they do create significant inequi- 1949 - * - lion, was 4.4 percent smaller than in ties as between different individuals. Workers with taxable wages in the second quarter of 1948 and 0.5 The following tabulation shows, for April-June 1949 numbered an esti- percent less than in the first quarter certain combinations of ages of male mated 38.5 million, representing a of 1949. These contraseasonal de- employee and wife, the factors that drop of 4.5 percent and 1.3 percent clines result from continuing adjust- will be applicable according to the law and those developed on a reasonable Table l.-Old-age and survivors insurance: Estimated number of employers * actuarial basis. and workers and estimated amount of wages in covered industries, by speci- fied period, 1940-49 In some instances the factors in the (Corrected to Nov. 1,1949] law are more generous by as much as - - - 80 or 90 percent, while for what might All Total pay rolls in Work- i vorkcrs r overed industries 8 be considered the typical case of a E I?rs with nplosed - - -- male employee aged 65 and his wife, 1.nxehle in I- NILWR overcd aged 60, the differential is more than Year and quarter during dust& (P xriod 2 Total 1l-wage iwing Total 1ivcrage 25 percent.