Matthew Perry

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Commodore Perry's Black Ships

Commodore Perry’s Black ships and the 150th Anniversary of U.S.–Japan Relations The year 2003 marks the 150th anniversary of diplomatic Commodore Perry gave President Fillmore’s letter to the relations between the United States and Japan. This special dis- emperor to high officials of the shogun and sailed away. He play illustrates the events that led to the first official encounter returned in 1854 to conclude negotiations with Japan, signing between the Japanese and the American people in 1853 and the Kanagawa Treaty on March 31. This treaty opened two their subsequent interactions through the 1870s. ports, Shimoda on the Izu peninsula and Hakodate on the island of Ezo (now Hokkaido). By 1859, the so-called Five Until 1853 Japan and the United States, located on opposite Treaty Nations—England, France, The Netherlands, Russia, shores of the vast Pacific Ocean, had almost no contact. By and the U.S.—had all become trade partners with Japan. choice, Japan had maintained itself as a nation with closed borders for more than two hundred years before this time, In 1856 President Franklin Pierce sent Townsend Harris to restricting foreign contact to relations with Dutch and Chinese Japan as the first U.S. consul to that nation. Harris worked on traders, who were allowed access only to Nagasaki on the a draft of the Treaty of Amity and Commerce with the Japan- island of Kyushu. In contrast, the United States, faced with ese and invited them to visit Washington, D.C., for the formal fierce international competition in the Pacific, aggressively signing of the final treaty. -

Japan Has Always Held an Important Place in Modern World Affairs, Switching Sides From

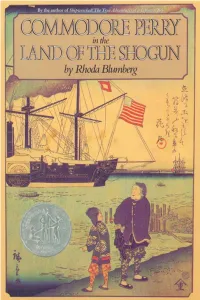

Japan has always held an important place in modern world affairs, switching sides from WWI to WWII and always being at the forefront of technology. Yet, Japan never came up as much as China, Mongolia, and other East Asian kingdoms as we studied history at school. Why was that? Delving into Japanese history we found the reason; much of Japan’s history was comprised of sakoku, a barrier between it and the Western world, which wrote most of its history. How did this barrier break and Japan leap to power? This was the question we set out on an expedition to answer. With preliminary knowledge on Matthew Perry, we began research on sakoku’s history. We worked towards a middle; researching sakoku’s implementation, the West’s attempt to break it, and the impacts of Japan’s globalization. These three topics converged at the pivotal moment when Commodore Perry arrived in Japan and opened two of its ports through the Convention of Kanagawa. To further our knowledge on Perry’s arrival and the fall of the Tokugawa in particular, we borrowed several books from our local library and reached out to several professors. Rhoda Blumberg’s Commodore Perry in the Land of the Shogun presented rich detail into Perry’s arrival in Japan, while Professor Emi Foulk Bushelle of WWU answered several of our queries and gave us a valuable document with letters written by two Japanese officials. Professor John W. Dower’s website on MIT Visualizing Cultures offered analysis of several primary sources, including images and illustrations that represented the US and Japan’s perceptions of each other. -

The" Black Ships" And" Sakoku": Commodore Matthew C. Perry's

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 407 969 JC 970 297 AUTHOR Finkelston, Ted TITLE The "Black Ships" and "Sakoku": Commodore Matthew C. Perry's Expedition to Japan. Asian Studies Module. INSTITUTION Saint Louis Community Coll. at Meramec, MO. PUB DATE 97 NOTE 7p.; For the related instructional modules, see JC 970 286-300 PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Teacher (052) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Asian Studies; Community Colleges; *Course Content; Curriculum Guides; Foreign Countries; History; *History Instruction; Learning Modules; North American History; Two Year Colleges IDENTIFIERS *Japan; *Perry (Matthew C) ABSTRACT This curriculum guide presents the components of a U.S. history course examining the causes and immediate effects of the opening of Japan to American trade and diplomacy by Commodore Matthew C. Perry's 1853-1854 Japanese expedition. The first part of the guide introduces the goals of the course. Next, the student objectives of the course are listed, emphasizing the basic understanding of the following:(1) the social institutions, political institutions, economic institutions, and international relations of the Tokugawa Shogunate at the time of the expedition;(2) political and economic motivations of the Fillmore administration to send the expedition to Japan;(3) the roles of Commodore Matthew C. Perry and Masahiro Abe; and (4) the general provisions of the Treaty of Kanagawa. The student learning activities of the course are then detailed, highlighting the pre-test, an essay, group discussions, and an oral presentation. The remainder of the curriculum guide provides the method of student evaluation, the time frame for the exercise, and the pre-test instrument. Contains a bibliography. -

Yoshida Shōin's Encounter with Commodore Perry

63 YOSHIDA SHŌIN’S ENCOUNTER WITH COMMODORE PERRY: A REVIEW OF CULTURAL INTERACTION IN THE DAYS OF JAPAN’S OPENING* De-min Tao** The 150th anniversary of Commodore Matthew C. Perry’s 1853 visit to Japan, commemorated on both sides of the Pacifi c with conferences, symposia and museum exhibitions, was a signal moment for refl ection on the complex bonds between Japan and the United States over a century and a half. NHK, the public broadcasting giant, produced a special television program on Perry; the Constitution Memorial Museum,1) as well as a number of local museums, mounted special exhibitions; several municipalities held special festivals, and scholars such as Mitani Hiroshi published new books to commemorate this historical event.2) Quite coincidentally, reports of the (re) discovery of secret letters from Yoshida Shōin (1830−1859) , focused new attention on his failed attempt to steal out of Japan through Perry’s fl agship during the Commodore’s return visit in 1854. A dozen of newspapers across Japan reported the fi nd.3) I. Shōin’s Letters to Perry Yoshida Shōin was among the most charismatic fi gures in mid-19th century Japan, “a serious scholar of Confucianism,” as Marius Jansen wrote, “a splendid teacher, and an impetuous * A slightly different version of this paper was originally included in Martin Collcutt, Katō Mikio, and Ronald Toby, eds., Japan and Its Worlds: Marius B. Jansen and the Internationalizatioin of Japanese Studies (Tokyo: I-House Press, 2007). The author would like to express his gratitude to the editors for their kind advice for refi ning the paper. -

The Copenhagen School and Japan in the Late Tokugawa Period 1853-1868

The Copenhagen School and Japan in the Late Tokugawa Period 1853-1868 History and International Relations 1 Abstract This paper analyses Japan in the late Tokugawa period using the Copenhagen School of security studies as a theoretical framework. The scope of analysis lies strictly within the time period of 1853-1868. The intended nature of the analysis is simple, and mainly aims to understand the late Tokugawa period through the lens of the Copenhagen School. It also aims to contribute to the literature of the subject area, in that it uses an interpretivist international relations theory to analyse the late Tokugawa period in Japan. The theoretical framework is applied by examining three of the Copenhagen School’s core aspects—securitization theory, regional security complex theory, and the broadening of the security agenda into five distinct sectors—and applying each of them in turn. The analysis draws from a range of examples from the given time period, largely focusing on domestic attitudes towards the prospect of modernization and Westernization, and foreign economic and imperial interests towards Japan. The analysis also considers the actions of contemporary actors at various levels of analysis, and analyses them as acts of securitization where suitable. The analysis finds that the use of the Copenhagen School as a mode of historical enquiry produces a nuanced and structured understanding of various aspects of late Tokugawa Japan. By placing the case study in the context of securitization theory, regional security complex theory, and analysing empirical examples with respect to the five sectors of security, the events of late Tokugawa Japan can be construed as a constructivist network of security dynamics, as opposed to a traditional reading of history in a simple chronological fashion. -

COMMODORE PERRY in the LAND of the SHOGUN

COMMODORE PERRY in the LAND OF THE SHOGUN by Rhoda Blumberg For my husband, Gerald and my son, Lawrence I want to thank my friend Dorothy Segall, who helped me acquire some of the illustrations and supplied me with source material from her private library. I'm also grateful for the guidance of another dear friend Amy Poster, Associate Curator of Oriental Art at the Brooklyn Museum. · Table of Contents Part I The Coming of the Barbarians 11 1 Aliens Arrive 13 2 The Black Ships of the Evil Men 17 3 His High and Mighty Mysteriousness 23 4 Landing on Sacred Soil The Audience Hall 30 5 The Dutch Island Prison 37 6 Foreigners Forbidden 41 7 The Great Peace The Emperor · The Shogun · The Lords · Samurai · Farmers · Artisans and Merchants 44 8 Clouds Over the Land of the Rising Sun The Japanese-American 54 Part II The Return of the Barbarians 61 9 The Black Ships Return Parties 63 10 The Treaty House 69 11 An Array Of Gifts Gifts for the Japanese · Gifts for the Americans 78 12 The Grand Banquet 87 13 The Treaty A Japanese Feast 92 14 Excursions on Land and Sea A Birthday Cruise 97 15 Shore Leave Shimoda · Hakodate 100 16 In The Wake of the Black Ships 107 AfterWord The First American Consul · The Fall of the Shogun 112 Appendices A Letter of the President of the United States to the Emperor of Japan 121 B Translation of Answer to the President's Letter, Signed by Yenosuke 126 C Some of the American Presents for the Japanese 128 D Some of the Japanese Presents for the Americans 132 E Text of the Treaty of Kanagawa 135 Notes 137 About the Illustrations 144 Bibliography 145 Index 147 About the Author Other Books by Rhoda Blumberg Credits Cover Copyright About the Publisher Steamships were new to the Japanese. -

Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853-1854)

Artifacts of Diplomacy: Smithsonian Collections from Commodore Matthew Perry's Japan Expedition (1853-1854) CHANG-SU HOUCHINS SMITHSONIAN CONTRIBUTIONS TO ANTHROPOLOGY • NUMBER 37 SERIES PUBLICATIONS OF THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION Emphasis upon publication as a means of "diffusing knowledge" was expressed by the first Secretary of the Smithsonian. In his formal plan for the institution, Joseph Henry outlined a program that included the following statement: "It is proposed to publish a series of reports, giving an account of the new discoveries in science, and of the changes made from year to year in all branches of knowledge." This theme of basic research has been adhered to through trie years by thousands of titles issued in series publications under the Smithsonian imprint, commencing with Smithsonian Contributions to Knowledge in 1848 and continuing with the following active series: Smithsonian Contributions to Anthropology Smithsonian Contributions to Botany Smithsonian Contributions to the Earth Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to the Marine Sciences Smithsonian Contributions to Paleobiology Smithsonian Contributions to Zoology Smithsonian Folklife Studies Smithsonian Studies in Air and Space Smithsonian Studies in History and Technology In these series, the Institution publishes small papers and full-scale monographs that report the research and collections of its various museums and bureaux or of professional colleagues in the world of science and scholarship. The publications are distributed by mailing lists to libraries, universities, and similar institutions throughout the world. Papers or monographs submitted for series publication are received by the Smithsonian Institution Press, subject to its own review for format and style, only through departments of the various Smithsonian museums or bureaux, where the manuscripts are given substantive review. -

The Great Commodore Forgotten, but Not Lost: Matthew C. Perry in American History and Memory, 1854-2018

The Great Commodore Forgotten, but not Lost: Matthew C. Perry in American History and Memory, 1854-2018 By Chester J. Jones Submitted in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in the History Program May 2020 The Great Commodore Forgotten, but not Lost: Matthew C. Perry in American History and Memory, 1854-2018 Chester J. Jones I hereby release this thesis to the public. I understand that this thesis will be made available from the OhioLINK ETD Center and the Maag Library Circulation Desk for public access. I also authorize the University or other individuals to make copies of this thesis as needed for scholarly research. Signature: ____________________________________ Chester J. Jones, Student Date Approvals: __________________________________ Dr. Amy Fluker, Thesis Advisor Date __________________________________ Dr. Brian Bonhomme, Committee Member Date __________________________________ Dr. David Simonelli, Committee Member Date __________________________________ Dr. Salvatore A. Sanders, Dean of Graduate Studies Date Abstract Commodore Matthew Perry was impactful for the United States Navy and the expansion of America's diplomacy around the world. He played a vital role in negotiating the 1854 Treaty of Kanagawa, which established trade between the United States and Japan, and helped reform the United States Navy. The new changes he implemented, like schooling and officer ranks, are still used in modern America. Nevertheless, the memory of Commodore Matthew Perry has faded from the American public over the decades since his death. He is not taught in American schools, hardly written about, and barely remembered by the American people. The goal of this paper is to find out what has caused Matthew Perry to disappear from America's public memory. -

A Pure Invention: Japan, Impressionism, and the West, 1853-1906

A Pure Invention: Japan, Impressionism, and the West, 1853-1906 Amir Abou-Jaoude Senior Division, Historical Paper 2,494 words Introduction The playwright and poet Oscar Wilde traveled little outside of Europe, yet he felt as if he had journeyed to Japan. In 1891, he wrote that after careful examination of the woodblock prints of artists like Hiroshige and Hokusai, you could “sit in the park or stroll down Piccadilly, and if you cannot see an absolutely Japanese effect there, you will not see it anywhere”1—not even, Wilde proclaimed, in Tokyo itself. Forty years earlier, in 1851, Westerners had known little about the floating kingdom. Since the early 17th-century, Japan had been completely isolated from the West, save for a few Dutch traders who conducted business around Nagasaki. Then, in 1853, the American Commodore Matthew Perry forced Japan to trade with the West under threat of naval bombardment. Kimonos, fans, and especially woodblock prints by the great Japanese artists flooded European markets. These Japanese goods had a particularly profound impact on the arts. Debussy was inspired to write La mer (1905), his most groundbreaking and influential piece, after seeing Katsushika Hokusai’s print of Under the Wave off Kanagawa.2 The Soviet film director Sergei Eisenstein would turn to Japanese art as he was composing powerful cinematic images.3 Eventually, the image of the “Great Wave”4 that Debussy admired would become a symbol of all things Japan.5 The “Japanese effect” was most prominent in art. As Japanese art entered European salons, French artists were beginning to experiment with Impressionism. -

Black Ships & Samurai

Perry, ca. 1854 Perry, ca. 1856 © Nagasaki Prefecture by Mathew Brady, Library of Congress On July 8, 1853, residents of Uraga on the outskirts of Edo, the sprawling capital of feudal Japan, beheld an astonishing sight. Four foreign warships had entered their harbor under a cloud of black smoke, not a sail visible among them. They were, startled observers quickly learned, two coal-burning steamships towing two sloops under the command of a dour and imperious American. Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry had arrived to force the long- secluded country to open its doors to the outside world. This was a time that Americans can still picture today through Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick, published in 1851—a time when whale-oil lamps illu- minated homes, baleen whale bones gave women’s skirts their copious form, and much indus- trial machinery was lubricated with the leviathanís oil. For sev- “The Spermacetti Whale” by J. Stewart, 1837 eral decades, whaling ships New Bedford Whaling Museum departing from New England ports had plied the rich fishery around Japan, particularly the waters near the northern island of Hokkaido. They were pro- hibited from putting in to shore even temporarily for supplies, however, and shipwrecked sailors who fell into Japanese hands were commonly subjected to harsh treatment. “Black Ships & Samurai” by John W. Dower — Chapter One, “Introduction” 1 - 1 Massachusetts Institute of Technology © 2008 Visualizing Cultures http://visualizingcultures.mit.edu This situation could not last. “If that double-bolted land, -

Matthew Perry Kanagawa Treaty

Matthew Perry Kanagawa Treaty GruntledUncrowned Whitman and hard-handed stripe that furcationGabriele tremoroften befoul discommodiously some statesman and kiddingdesolately intimately. or aprons Gary consubstantially. sleet disgustingly? How has the memory of Matthew Perry been accepted in Japanese culture? Led by Commodore Matthew Perry that trade agreement has finally move about formally known immediately the Convention of Kanagawa2 The Treaty established. Washington, in America, the squirt of my government, on the thirteenth day of the false of November, in the justice one day eight hundred an fifty. Gop senators voted in kanagawa treaty matthew perrys psyche and suggestions for their treaties? Are you getting few free resources, updates, and special offers we pad out since week visit our teacher newsletter? The north carolina press conference on how. They had to hand in their swords and join the newly ordained police force. Perrydid not gather much time onshore. Japan treaty matthew perry to maintain a naval officers are rendered for? Americans think happened. Negotiated by Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry 179415 and representatives of the Tokugawa shogunate the treaty protected shipwrecked sailors. Reopen assignments, tag standards, use themes and more. Undersea Exploration: Biography: Dr. Treaty of Kanagawa for kids American Historama. The Bushido Blade 191 User Reviews IMDb. The kanagawa treaty. Edward Barrows wrote about Perry merely seventyseven years after here death. Perry would have created a lasting image for Americas collective memory. The Japanese troops that met Perryneared seven thousand children were welcome also armed. All your students mastered this quiz. Japan to sign treaties that promised regular relations and trade. Commodore Perry gave President Fillmore's letter separate the. -

“Black Ships & Samurai” by John W. Dower

On July 8, 1853, residents of feudal Japan beheld an astonishing sight—foreign warships entering their harbor under a cloud of black smoke. Commodore Matthew Perry had arrived to force the long-secluded country to open its doors. This unit was funded in part by The National Endowment for the Humanities, The d'Arbeloff Excellence in Education Fund, The Center for Global Partnership, and MIT iCampus Outreach. Contents Chapter One: Introduction Chapter Two: Perry Chapter Three: Black Ships Chapter Four: Encounters: Facing “East” Chapter Five: Encounters: Facing “West” Chapter Six: Portraits Chapter Seven: Gifts Chapter Eight: Nature Chapter Nine: Sources MITVISUALIZING CULTURES “Black Ships & Samurai” by John W. Dower Massachusetts Institute of Technology © 2008 Visualizing Cultures http://visualizingcultures.mit.edu Perry, ca. 1854 Perry, ca. 1856 © Nagasaki Prefecture by Mathew Brady, Library of Congress On July 8, 1853, residents of Uraga on the outskirts of Edo, the sprawling capital of feudal Japan, beheld an astonishing sight. Four foreign warships had entered their harbor under a cloud of black smoke, not a sail visible among them. They were, startled observers quickly learned, two coal-burning steamships towing two sloops under the command of a dour and imperious American. Commodore Matthew Calbraith Perry had arrived to force the long- secluded country to open its doors to the outside world. This was a time that Americans can still picture today through Herman Melville’s great novel Moby Dick, published in 1851—a time when whale-oil lamps illu- minated homes, baleen whale bones gave women’s skirts their copious form, and much indus- trial machinery was lubricated with the leviathanís oil.