Natural Curiosity. Unseen Art of Australia's First Fleet

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

AUSTRALIA DAY HOMEWORK CONTRACT – Week 1

HOMEWORK CONTRACT – Week 1 Write your spelling words each day using LOOK – SAY – COVER – WRITE - CHECK Monday Tuesday Wednesday Thursday AUSTRALIA DAY On the 26th January 1788, Captain Arthur 1) When is Australia Day ? Phillip and the First Fleet arrived at Sydney ______________________________________ Cove. The 26th January is celebrated each 2) Why do we celebrate Australia Day? year as Australia Day. This day is a public ______________________________________ holiday. There are many public celebrations to take part in around the country on 3) What ceremonies take place on Australia Day? Australia Day. Citizenship ceremonies take ______________________________________ place on Australia Day as well as the 4) What are the Australian of the Year and the presentation of the Order of Australia and Order of Australia awarded for? Australian of the Year awards for ______________________________________ outstanding achievement. It is a day of 5) Name this year’s Australian of the Year. great national pride for all Australians. ______________________________________ Correct the following paragraph. Write the following words in Add punctuation. alphabetical order. Read to see if it sounds right. Australia __________________ our family decided to spend australia day at the flag __________________ beach it was a beautiful sunny day and the citizenship __________________ celebrations __________________ beach was crowded look at all the australian ceremonies __________________ flags I said. I had asked my parents to buy me Australian __________________ a towel with the australian flag on it but the First Fleet __________________ shop had sold out awards __________________ Circle the item in each row that WAS NOT invented by Australians. boomerang wheel woomera didgeridoo the Ute lawn mower Hills Hoist can opener Coca-Cola the bionic ear Blackbox Flight Recorder Vegemite ©TeachThis.com.au HOMEWORK CONTRACT – Week 1 Created by TeachThis.com.au Number Facts Problem solving x 4 3 5 9 11 1. -

Parramatta's Archaeological Landscape

Parramatta’s archaeological landscape Mary Casey Settlement at Parramatta, the third British settlement in Australia after Sydney Cove and Norfolk Island, began with the remaking of the landscape from an Aboriginal place, to a military redoubt and agricultural settlement, and then a township. There has been limited analysis of the development of Parramatta’s landscape from an archaeological perspective and while there have been numerous excavations there has been little exploration of these sites within the context of this evolving landscape. This analysis is important as the beginnings and changes to Parramatta are complex. The layering of the archaeology presents a confusion of possible interpretations which need a firmer historical and landscape framework through which to interpret the findings of individual archaeological sites. It involves a review of the whole range of maps, plans and images, some previously unpublished and unanalysed, within the context of the remaking of Parramatta and its archaeological landscape. The maps and images are explored through the lense of government administration and its intentions and the need to grow crops successfully to sustain the purposes of British Imperialism in the Colony of New South Wales, with its associated needs for successful agriculture, convict accommodation and the eventual development of a free settlement occupied by emancipated convicts and settlers. Parramatta’s river terraces were covered by woodlands dominated by eucalypts, in particular grey box (Eucalyptus moluccana) and forest -

EORA Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770–1850 Exhibition Guide

Sponsored by It is customary for some Indigenous communities not to mention names or reproduce images associated with the recently deceased. Members of these communities are respectfully advised that a number of people mentioned in writing or depicted in images in the following pages have passed away. Users are warned that there may be words and descriptions that might be culturally sensitive and not normally used in certain public or community contexts. In some circumstances, terms and annotations of the period in which a text was written may be considered Many treasures from the State Library’s inappropriate today. Indigenous collections are now online for the first time at <www.atmitchell.com>. A note on the text The spelling of Aboriginal words in historical Made possible through a partnership with documents is inconsistent, depending on how they were heard, interpreted and recorded by Europeans. Original spelling has been retained in quoted texts, while names and placenames have been standardised, based on the most common contemporary usage. State Library of New South Wales Macquarie Street Sydney NSW 2000 Telephone (02) 9273 1414 Facsimile (02) 9273 1255 TTY (02) 9273 1541 Email [email protected] www.sl.nsw.gov.au www.atmitchell.com Exhibition opening hours: 9 am to 5 pm weekdays, 11 am to 5 pm weekends Eora: Mapping Aboriginal Sydney 1770–1850 was presented at the State Library of New South Wales from 5 June to 13 August 2006. Curators: Keith Vincent Smith, Anthony (Ace) Bourke and, in the conceptual stages, by the late Michael -

History of New South Wales from the Records

This is a digital copy of a book that was preserved for generations on library shelves before it was carefully scanned by Google as part of a project to make the world's books discoverable online. It has survived long enough for the copyright to expire and the book to enter the public domain. A public domain book is one that was never subject to copyright or whose legal copyright term has expired. Whether a book is in the public domain may vary country to country. Public domain books are our gateways to the past, representing a wealth of history, culture and knowledge that's often difficult to discover. Marks, notations and other marginalia present in the original volume will appear in this file - a reminder of this book's long journey from the publisher to a library and finally to you. Usage guidelines Google is proud to partner with libraries to digitize public domain materials and make them widely accessible. Public domain books belong to the public and we are merely their custodians. Nevertheless, this work is expensive, so in order to keep providing this resource, we have taken steps to prevent abuse by commercial parties, including placing technical restrictions on automated querying. We also ask that you: + Make non-commercial use of the files We designed Google Book Search for use by individuals, and we request that you use these files for personal, non-commercial purposes. + Refrain from automated querying Do not send automated queries of any sort to Google's system: If you are conducting research on machine translation, optical character recognition or other areas where access to a large amount of text is helpful, please contact us. -

Intermediate a New Life Australia Worksheet 8: the First Fleet

Intermediate A New Life Australia Worksheet 8: The First Fleet Copyright With the exception of the images contained in this document, this work is © Commonwealth of Australia 2011. You may download, display, print and reproduce this material in unaltered form only for your personal, non- commercial use or use within your organisation for the purposes of the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP). Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. Use of all or part of this material must include the following attribution: © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This document must be attributed as [Intermediate A New Life Australia – Worksheet 8: The First Fleet]. Any enquiries concerning the use of this material should be directed to: The Copyright Officer Department of Education and Training Location code C50MA10 GPO Box 9880 Canberra ACT 2601 or emailed to [email protected]. Images ©2011 Photos.com, a division of Getty Images. All rights reserved. Images reproduced with permission. Acknowledgements The AMEP is funded by the Australian Government Department of Education and Training. Disclaimer While the Department of Education and Training and its contributors have attempted to ensure the material in this booklet is accurate at the time of release, the booklet contains material on a range of matters that are subject to regular change. No liability for negligence or otherwise is assumed by the department or its contributors should anyone suffer a loss or damage as a result of relying on the information provided in this booklet. References to external websites are provided for the reader’s convenience and do not constitute endorsement of the information at those sites or any associated organisation, product or service. -

MOYLE, Edward Aboard First Fleet Scarborough 1788

EDWARD MOYLE - FIRST FLEET - One of 208 Convicts Transported on “Scarborough” 1788 Sentenced to 7 years at Cornwall Assizes Transported to New South Wales NAME: EDWARD MOYLE ALIAS: Edward Miles KNOWN AS: Edward was tried as MOYLE but used the name MILES from the time of his arrival at Port Jackson AGE: 24 BORN: 1761; (or, about 1757 at Launceston-Cornwall (Convict Stockade) BAPTISED: 6 April 1761, Wendron-Cornwall * DIED: 19 August 1838, Windsor-NSW BURIED: August 1838, St Matthews, Windsor-NSW * The IGI shows this family as Edward Moyle and Elizabeth Uren, with eight children including Edward Moyle, baptised 5 April 1761 at Wendron, and buried 20 November 1785 – possibly the wrong family or just the wrong burial, as there is more than one Edward Moyle in Wendron - http://archiver.rootsweb.ancestry.com/th/read/AUS-CONVICTS/2004-02/1076207727 TRIED: 19 March 1785, Launceston-Cornwall SENTENCE: Death Sentence recorded. Reprieved. Transportation for 7 years CRIME: Stealing two cloth waistcoats and other items TRIED WITH: John Rowe BODMIN GAOL: 19 March 1785, Edward Moyle for stealing 2 cloth waistcoats and other items, Death commuted to 7 years transportation SHIP: Taken aboard the “Charlotte” before being transferred to “Scarborough” - Departed Portsmouth on 13 May 1787, carrying 208 male convicts (no deaths) and arrived in New South Wales on 26 January 1788. Master John Marshall, Surgeon Denis Considen THE FIRST FLEET - Six transport ships, two naval escorts, and three supply ships – began the European colonisation of the Australian continent. New South Wales was proclaimed upon their arrival at Sydney Cove on 26 January 1788. -

Promiscuous Provenance, Anna Glynn

Colonial Hybrid Reimagined from Raper – Gum-plant, & kangooroo of New-Holland 1789, 2017 Ink, watercolour and pencil on Arches paper 66 x 51 cm FOREWORD Anna Glynn has been a firm supporter of the Anna’s work has been described variously as ‘a Shoalhaven Regional Gallery since it opened in 2004. romantic and beautiful style’ (Zhang Tiejun, General Her exhibitions and commissions have always been Manager, Harmony Art and Culture, 2012), ‘derived well received and her increasing profile as an from a physical and mental excursion into the Australian artist of note has been a source of pride Australian landscape and its myths’ (Arthur Boyd, for many in the community. 1997) and ‘a pure and innovative realm through which When invited to view some of Anna’s new works people can understand nature and life’ (Wang Wuji, and asked to offer comment on the direction she was 2012). In Promiscuous Provenance, Anna has drawn on exploring in her pen and ink pieces, I was delighted to her wide ranging art practise and brought her sense of PROMISCUOUS PROVENANCE view two works that clearly referenced Australian humour and delicate touch to works that are colonial works. These pieces stood out both in the challenging, engaging and intellectually rigorous. detail and beauty of the work, but also for the care It is important that in modern Australia we stop at 4 that had been taken in the research and observation regular intervals and review our history. That we find 5 of the oddities of colonial interpretations of different ways to shine a light on the difficult and ugly Australian animals. -

![An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/2437/an-account-of-the-english-colony-in-new-south-wales-volume-1-822437.webp)

An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1]

An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country. To Which are Added, Some Particulars of New Zealand: Complied by Permission, From the Mss. of Lieutenant-Governor King Collins, David (1756-1810) A digital text sponsored by University of Sydney Library Sydney 2003 colacc1 http://purl.library.usyd.edu.au/setis/id/colacc1 © University of Sydney Library. The texts and images are not to be used for commercial purposes without permission Prepared from the print edition published by T. Cadell Jun. and W. Davies 1798 All quotation marks are retained as data. First Published: 1798 F263 Australian Etext Collections at Early Settlement prose nonfiction pre-1810 An Account of the English Colony in New South Wales [Volume 1] With Remarks on the Dispositions, Customs, Manners &c. of the Native Inhabitants of that Country. To Which are Added, Some Particulars of New Zealand: Complied by Permission, From the Mss. of Lieutenant-Governor King Contents. Introduction. SECT. PAGE I. TRANSPORTS hired to carry Convicts to Botany Bay. — The Sirius and the Supply i commissioned. — Preparations for sailing. — Tonnage of the Transports. — Numbers embarked. — Fleet sails. — Regulations on board the Transports. — Persons left behind. — Two Convicts punished on board the Sirius. — The Hyæna leaves the Fleet. — Arrival of the Fleet at Teneriffe. — Proceedings at that Island. — Some Particulars respecting the Town of Santa Cruz. — An Excursion made to Laguna. — A Convict escapes from one of the Transports, but is retaken. — Proceedings. — The Fleet leaves Teneriffe, and puts to Sea. -

Australia Day

Australia Day Days and weeks celebrated or commemorated in Australia (including Australia Day. ANZAC Day. Harmony Week. Notional Reconciliation Week, NAIDOC Week and Notional Sorry Day) and the importance of symbols and emblems 01~ (ACHHK063) Time line Teacher information (Events connected with Elaboration Australia Day) Understands the significance of Australia Day and some arguments for and against the woy it is celebrated. .···• 13 May 1787 Ships of the First Fleet. Key Inquiry questions under the command of Who lived here first and ho v do we know? Captain Arthur Phillip. leave Portsmouth. England Ho v and why do people choose to remember significant events of the post? Historical skills 26 January 1788 !····• • Use historical terms (ACHHS066) D . First Fleet arrives in Port Jackson. Sydney Cove • looote relevant information from sources provided (ACHHS068) • Identify different points of view (ACHHS069) • :····• 1818 • Develop texts. particularly narratives (ACHHS070) . First official celebrations to mark 30th anniversary of • Use a range of communication forms (oral. graphic. written) white seHiement and digital technologies (ACHHS071) Historical concepts :····• 1938 • Sources • Continuity and change • Couse and effect • Significance Aboriginal activists organise o 'Day of ourning· protest on • Empathy • Perspectives 150th anniversary of while seHiement rB Background information ----------------- ; ••••• 1930 • Captain Arthur Phillip. o former and sailor. led the First Fleet of 11 ships of approximately 1500 All states/territories recognise men. women and children. Six of the ships vere for convicts. Captain Phillip become the leader the ondoy closest to 26 of the settlement at Port Jackson (renamed Sydney). January as o notional public • Australia Day hos become Australia's single biggest day of celebration ond has become holiday to celebrate Australia synonymous with community. -

Course Number and Title: CAS AH 374 Australian Art and Architecture

Course Number and Title: CAS AH 374 Australian Art and Architecture Instructor/s Name/s: Peter Barnes Course Dates: Spring Semester, Fall Semester Office Location: BU Sydney Programs, Australia, a division of BU Study Abroad Course Time: Two sessions per week in accordance with class schedule: one session of 4 + hours and one session of 2 hours in a 7-8 week teaching half of a semester. Location: Classrooms, BU Sydney Academic Centre, Sydney, Australia, and multiple out-of-classroom field trips as scheduled, one of which is a 12 hour day long field trip outside the city to Canberra, Australia’s national capital and home to National Art Galleries, and Museums. Course Credits: 4 BU credits plus 2 BU Hub units Contact Information: [email protected] Office Hours: 15 minutes prior to and following course delivery or by appointment. TA/TF/Learning Assistant information, if relevant: 0 Principal Lecturers: Peter Barnes Guest Lecturers: Vary in accordance with available artists. One example is: Tom Carment, a working artist Question-driven Course Description: *How have European art traditions influenced the art practice of Australia’s indigenous peoples and how in turn has Aboriginal culture impacting the art of non-indigenous Australians? *The 18th century voyages to the southern ocean placed artists in a prominent role as practitioners of the new science of observation and experimentation promoted by the Royal Society. How does this differ from the idealist aesthetics of the Royal academy and what impact did this have on art in Australia during -

L3-First-Fleet.Pdf

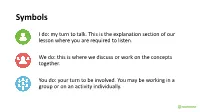

Symbols I do: my turn to talk. This is the explanation section of our lesson where you are required to listen. We do: this is where we discuss or work on the concepts together. You do: your turn to be involved. You may be working in a group or on an activity individually. Life in Britain During the 1700s In the 1700s, Britain was the wealthiest country in the world. Rich people could provide their children with food, nice clothes, a warm house and an education. While some people were rich, others were poor. Poor people had no money and no food. They had to work as servants for the rich. Poor children did not attend school. When machines were invented, many people lost their jobs because workers were no longer needed. Health conditions during the 1700s were very poor. There was no clean water due to the pollution from factories. Manure from horses attracted flies, which spread diseases. A lack of medical care meant many people died from these diseases. Life in Britain During the 1700s • The overcrowded city streets were not a nice place to be during the 1700s. High levels of poverty resulted in a lot of crime. • Harsh punishments were put in place to try to stop the crime. People were convicted for crimes as small as stealing bread. Soon, the prisons became overcrowded with convicts. • One of the most common punishments was transportation to another country. Until 1782, Britain sent their convicts to America. After the War of Independence in 1783, America refused to take Britain’s convicts. -

Excavation of Buildings in the Early Township of Parramatta

AUSTRALIAN HISTORICAL ARCHAEOLOGY, 5,1987 The Excavation of Buildings in the Early Township of Parramatta, New South Wales, 1790-1820s EDWARD HIGGINBOTHAM This paper describes the excavation of a convict hut, erected in 1790 in Parramatta, together with an adjoining contemporary out-building or enclosure. It discusses the evidence for repair, and secondary occupation by free persons, one of whom is tentatively identified. The site produced the first recognised examples of locally manufactured earthenware. The historical and archaeological evidence for pottery manufacture in New South Wales between 1790 and 1830 is contained in an appendix. INTRODUCTION Before any archaeological excavation could take place, it was necessary to research the development of the township In September 1788 the wheat crop failed at Sydney Cove from historical documentation, then to establish whether any and also at Norfolk Island, partly because the seed had not items merited further investigation, and finally to ascertain been properly stored during the voyage of the First Fleet. As whether any archaeological remains survived later soon as this was known the Sirius was sent to the Cape of development. Good Hope for both flour and seed grain.' Also in November Preliminary historical research indicated that the area 1788 an agricultural settlement was established at Rose Hill available for archaeological investigation was initially (Parramatta).2 The intention was to clear sufficient land in occupied by a number of huts for convict accommodation, advance of the ship's return, so that the grain could be and subsequently by residential development.8 This paper is immediately sown. The early settlement at Rose Hill was an therefore mainly concerned with the development of convict attempt to save the penal colony from starvation, and and then domestic occupation in Parramatta.