Poemgroups in No Thanks Michael Webster

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MLA In-Text Citations

1 MLA In-Text Collin College–Frisco, Lawler Hall 141 972-377-1080 ▪ [email protected] Citations Appointments: collin.mywconline.net Short Quotations Prose: Less than four (4) typed lines of prose is considered to be a short quotation. • Quotations should always be incorporated into a sentence of your original prose. A quotation should never stand alone in a sentence. • Follow each quotation with a parenthetical in-text citation containing: o Author’s last name (unless the author is introduced in your sentence) o Page number from which the quotation was taken. • The period comes after the parenthetical citation. A question mark or exclamation point should be placed within the quotation if it is part of the quoted section, with a period following the parenthetical citation. Example: According to John Brown, the writing center proves to be a “calm and quiet area to learn more about writing techniques” (22). Poetry: Three (3) lines or less of a poem is a short quotation. • In the parenthetical citation, use line number(s) instead of page numbers • The first time you quote a poem, use the word “line” or “lines.” In subsequent references, only include the actual line numbers. • Indicate each line break with a slash (/), placing a space both before and after it. • Use two slashes to indicate a stanza break. • A verse play, such as those written by Shakespeare, follows the rules for poetry. Example: The closing lines of Frost’s poem have a sleepy, dream-like quality: “The only other sound’s the sweep / Of easy wind and downy flake // The woods are lovely, dark and deep” (lines 11-13). -

Introduction to Meter

Introduction to Meter A stress or accent is the greater amount of force given to one syllable than another. English is a language in which all syllables are stressed or unstressed, and traditional poetry in English has used stress patterns as a fundamental structuring device. Meter is simply the rhythmic pattern of stresses in verse. To scan a poem means to read it for meter, an operation whose noun form is scansion. This can be tricky, for although we register and reproduce stresses in our everyday language, we are usually not aware of what we’re going. Learning to scan means making a more or less unconscious operation conscious. There are four types of meter in English: iambic, trochaic, anapestic, and dactylic. Each is named for a basic foot (usually two or three syllables with one strong stress). Iambs are feet with an unstressed syllable, followed by a stressed syllable. Only in nursery rhymes to do we tend to find totally regular meter, which has a singsong effect, Chidiock Tichborne’s poem being a notable exception. Here is a single line from Emily Dickinson that is totally regular iambic: _ / │ _ / │ _ / │ _ / My life had stood – a loaded Gun – This line serves to notify readers that the basic form of the poem will be iambic tetrameter, or four feet of iambs. The lines that follow are not so regular. Trochees are feet with a stressed syllable, followed by an unstressed syllable. Trochaic meter is associated with chants and magic spells in English: / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Double, double, toil and trouble, / _ │ / _ │ / _ │ / _ Fire burn and cauldron bubble. -

The Waste Land by T

The Waste Land by T. S. Eliot Copyright Notice ©1998−2002; ©2002 by Gale. Gale is an imprint of The Gale Group, Inc., a division of Thomson Learning, Inc. Gale and Design® and Thomson Learning are trademarks used herein under license. ©2007 eNotes.com LLC ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. No part of this work covered by the copyright hereon may be reproduced or used in any form or by any means graphic, electronic, or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, taping, Web distribution or information storage retrieval systems without the written permission of the publisher. For complete copyright information on these eNotes please visit: http://www.enotes.com/waste−land/copyright Table of Contents 1. The Waste Land: Introduction 2. Text of the Poem 3. T. S. Eliot Biography 4. Summary 5. Themes 6. Style 7. Historical Context 8. Critical Overview 9. Essays and Criticism 10. Topics for Further Study 11. Media Adaptations 12. What Do I Read Next? 13. Bibliography and Further Reading 14. Copyright Introduction Because of his wide−ranging contributions to poetry, criticism, prose, and drama, some critics consider Thomas Sterns Eliot one of the most influential writers of the twentieth century. The Waste Land can arguably be cited as his most influential work. When Eliot published this complex poem in 1922—first in his own literary magazine Criterion, then a month later in wider circulation in the Dial— it set off a critical firestorm in the literary world. The work is commonly regarded as one of the seminal works of modernist literature. Indeed, when many critics saw the poem for the first time, it seemed too modern. -

Quoting Literature –Basic MLA Rules

QUOTING LITERATURE: Basic MLA Rules Prepared by Dr. Mira Sakrajda, Professor, English Department, Westchester Community College ______________________________________________________________ I. POETRY When you quote poetry, pay close attention to the poem’s original division into lines. If you quote one line of a poem, incorporate it into your sentence, using quotation marks and the line number in parentheses. If the quote ends your sentence, place the period after the parenthetical reference, not before it. From an essay on William Blake’s “The Clod and the Pebble”: Having focused on the selflessness of love in the first stanza, Blake challenges the reader’s understanding of this concept by saying that “Love seeketh only self to please” (9). If you quote two to three lines, add slash marks, with a space on either side, to indicate line division. From an essay on Emily Dickinson’s “Much Madness is divinest Sense –”: Dickinson draws a sharp contrast between society’s treatment of conformists and nonconformists: “Assent – and you are sane. / Demure – you are straightway dangerous and handled with a chain” (6-7). If you quote more than three lines, set the quote off one inch from the left margin (double the typical paragraph indent). The set-off quote should look like a perfect photocopy of the original in terms of layout, capitalization, and line division. Do not use quotation marks for a set-off quote, but do indicate line numbers in parentheses after the quote. From an essay on Robert Frost’s “Birches”: I have two children, three part-time jobs and four mid-terms next week, but I love my life and I totally identify with the speaker of “Birches” when he says: I’d like to get away from earth awhile And then come back to it and begin over. -

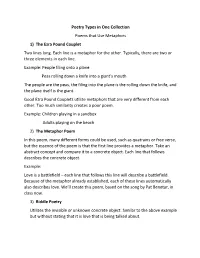

Poetry Types in One Collection Poems That Use Metaphors 1) the Ezra Pound Couplet Two Lines Long. Each Line Is a Metaphor for the Other

Poetry Types in One Collection Poems that Use Metaphors 1) The Ezra Pound Couplet Two lines long. Each line is a metaphor for the other. Typically, there are two or three elements in each line. Example: People filing onto a plane Peas rolling down a knife into a giant’s mouth The people are the peas, the filing into the plane is the rolling down the knife, and the plane itself is the giant. Good Ezra Pound Couplets utilize metaphors that are very different from each other. Too much similarity creates a poor poem. Example: Children playing in a sandbox Adults playing on the beach 2) The Metaphor Poem In this poem, many different forms could be used, such as quatrains or free verse, but the essence of the poem is that the first line provides a metaphor. Take an abstract concept and compare it to a concrete object. Each line that follows describes the concrete object. Example: Love is a battlefield – each line that follows this line will describe a battlefield. Because of the metaphor already established, each of these lines automatically also describes love. We’ll create this poem, based on the song by Pat Benetar, in class now. 3) Riddle Poetry Utilizes the invisible or unknown concrete object. Similar to the above example but without stating that it is love that is being talked about. Dylan Thomas portraits – this is a three line poem that asks a question which is answered by 4-6 word pairs ending in “ing”. Here is an example: Have you ever seen the rain? Life-giving, ground-soaking Mud-making, tires-spinning Haiku – Japanese three line poem with a 5-7-5 syllable pattern. -

Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion

APPENDIX B Basic Guide to Latin Meter and Scansion Latin poetry follows a strict rhythm based on the quantity of the vowel in each syllable. Each line of poetry divides into a number of feet (analogous to the measures in music). The syllables in each foot scan as “long” or “short” according to the parameters of the meter that the poet employs. A vowel scans as “long” if (1) it is long by nature (e.g., the ablative singular ending in the first declen- sion: puellā); (2) it is a diphthong: ae (saepe), au (laudat), ei (deinde), eu (neuter), oe (poena), ui (cui); (3) it is long by position—these vowels are followed by double consonants (cantātae) or a consonantal i (Trōia), x (flexibus), or z. All other vowels scan as “short.” A few other matters often confuse beginners: (1) qu and gu count as single consonants (sīc aquilam; linguā); (2) h does NOT affect the quantity of a vowel Bellus( homō: Martial 1.9.1, the -us in bellus scans as short); (3) if a mute consonant (b, c, d, g, k, q, p, t) is followed by l or r, the preced- ing vowel scans according to the demands of the meter, either long (omnium patrōnus: Catullus 49.7, the -a in patrōnus scans as long to accommodate the hendecasyllabic meter) OR short (prō patriā: Horace, Carmina 3.2.13, the first -a in patriā scans as short to accommodate the Alcaic strophe). 583 40-Irby-Appendix B.indd 583 02/07/15 12:32 AM DESIGN SERVICES OF # 157612 Cust: OUP Au: Irby Pg. -

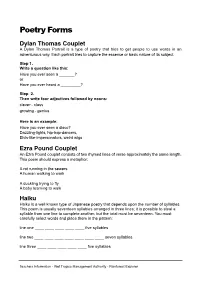

Poetry Forms Dylan Thomas Couplet a Dylan Thomas Portrait Is a Type of Poetry That Tries to Get People to Use Words in an Adventurous Way

Poetry Forms Dylan Thomas Couplet A Dylan Thomas Portrait is a type of poetry that tries to get people to use words in an adventurous way. Each portrait tries to capture the essence or basic nature of its subject. Step 1. Write a question like this: Have you ever seen a _______? or Have you ever heard a _________? Step 2. Then write four adjectives followed by nouns: clever - class growing - genius Here is an example: Have you ever seen a disco? Dazzling-lights, hip-hop-dancers, Elvis-like-impersonators, weird wigs Ezra Pound Couplet An Ezra Pound couplet consists of two rhymed lines of verse approximately the same length. This poem should express a metaphor: A rat running in the sewers A human walking to work A duckling trying to fly A baby learning to walk Haiku Haiku is a well known type of Japanese poetry that depends upon the number of syllables. This poem is usually seventeen syllables arranged in three lines; it is possible to steal a syllable from one line to complete another, but the total must be seventeen. You must carefully select words and place them in the pattern: line one ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ five syllables line two ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ seven syllables line three ____ ____ ____ ____ ____ five syllables Teachers Information - Wet Tropics Management Authority - Rainforest Explorer The first two lines should create a vivid picture and the third line should provide some insight into the picture. These poems should concern themselves with nature. Shape Poem This is a free-form poem published in the shape of something which exists in real life, in this instance it could be in the shape of a leaf, animal or buttress root. -

Elements of Poetry.Pdf

Elements of Poetry Alliteration is a repetition of the same consonant sounds in a sequence of words, usually at the beginning of a word or stressed syllable: “descending dew drops;” “luscious lemons.” Alliteration is based on the sounds of letters, rather than the spelling of words; for example, “keen” and “car” alliterate, but “car” and “cite” do not. Assonance is the repetition of similar internal vowel sounds in a sentence or a line of poetry, as in “I rose and told him of my woe.” Figurative language is a form of language use in which the writers and speakers mean something other than the literal meaning of their words. Two figures of speech that are particularly important for poetry are simile and metaphor. A simile involves a comparison between unlike things using like or as. For instance, “My love is like a red, red rose.” A metaphor is a comparison between essentially unlike things without a word such as like or as. For example, “My love is a red, red rose.” Synecdoche is a type of metaphor in which part of something is used to signify the whole, as when a gossip is called a “wagging tongue.” Metonymy is a type of metaphor in which something closely associated with a subject is substituted for it, such as saying the “silver screen” to mean motion pictures. Imagery is the concrete representation of a sense impression, feeling, or idea that triggers our imaginative ere-enactment of a sensory experience. Images may be visual (something seen), aural (something heard), tactile (something felt), olfactory (something smelled), or gustatory (something tasted). -

Shakespeare's Language

This document is designed as a resource for teachers which can be adapted to use with your students. Shakespeare's Language Introduction In Shakespeare's words lie all the clues to character and situation that any reader or actor needs. It's simply a matter of knowing how to find them. The clues are not necessarily in the meanings of the words - the rhythms of the language and the patterns and sounds of the words contain a great deal of valuable information. Here are some suggestions for finding the clues in Shakespeare's language: Blank verse Both written and spoken language use rhythm - a pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. Most forms of poetry or verse take rhythm one step further and regularise the rhythm into a formal pattern of stressed and unstressed syllables. A formal pattern of rhythm is called metre. Shakespeare writes either in blank verse, in rhymed verse or in prose. Blank verse is unrhymed but uses a regular pattern of rhythm or metre. In the English language, blank verse is iambic pentameter. Pentameter means there are five poetic feet. In iambic pentameter each of these five feet is composed of two syllables: the first unstressed; the second stressed. The opening line of Twelfth Night, is a perfect iambic line : 'If music be the food of love play on' With its unstressed and stressed syllables marked or 'scanned', it looks like this: / ں / ں / ں / ں / ں 'If mu sic be the food of love play on' weak / = strong = ں The rhythm of blank verse is conversational and with its dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM, dee DUM rhythm, it imitates the heartbeat. -

The Annotated Waste Land with Eliot's Contemporary Prose

the annotated waste land with eliot’s contemporary prose edited, with annotations and introduction, by lawrence rainey The Annotated Waste Land with Eliot’s Contemporary Prose Second Edition yale university press new haven & london First published 2005 by Yale University Press. Second Edition published 2006 by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2005, 2006 by Lawrence Rainey. All rights reserved. This book may not be reproduced, in whole or in part, including illustrations, in any form (beyond that copying permitted by Sections 107 and 108 of the U.S. Copyright Law and except by reviewers for the public press), without written permission from the publishers. Set in Scala by Duke & Company, Devon, Pennsylvania Printed in the United States of America. Library of Congress Control Number: 2006926386 A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library. The paper in this book meets the guidelines for permanence and durability of the Commit- tee on Production Guidelines for Book Longevity of the Council on Library Resources. ISBN-13: 978-0-300-11994-7 (pbk. : alk. paper) ISBN-10: 0-300-11994-1 (pbk. : alk. paper) 10987654321 contents introduction 1 A Note on the Text 45 the waste land 57 Editor’s Annotations to The Waste Land 75 Historical Collation 127 eliot’s contemporary prose London Letter, March 1921 135 The Romantic Englishman, the Comic Spirit, and the Function of Criticism 141 The Lesson of Baudelaire 144 Andrew Marvell 146 Prose and Verse 158 vi contents London Letter, May 1921 166 John Dryden 172 London Letter, July 1921 183 London Letter, September 1921 188 The Metaphysical Poets 192 Notes to Eliot’s Contemporary Prose 202 selected bibliography 251 general index 261 index to eliot’s contemporary prose 267 Illustrations follow page 74 the annotated waste land with eliot’s contemporary prose Introduction Lawrence Rainey when donald hall arrived in London in September 1951, bear- ing an invitation to meet the most celebrated poet of his age, T. -

Alliteration 2

HOW TO WRITE POETRY 1 Alliteration This verse uses alliteration and counting, beginning at one and working up to ten. Each word in each line begins with the sound that the number begins with. For example: One wild walrus or One wandering wolf or One wily woodpecker. Notice that although the word “one” begins with the letter “o”, the sound is “w”. Look at the example. One wandering wallaby, Two terrible tarantulas, Three thriving thrips, Four frantic flamingos, Five fierce falcons, Six slippery sturgeon, Seven silent stingrays, Eight aging aphid, Nine naughty newts, Ten terrible toads, All came home for tea. ……………………………………… 2 Definition Poems This form is built up in the following way: • Think of a subject • Think of three words the describe the subject • Add a group of words, or phrase to complete the image. My Kitten Soft, Black, Fluffy Snoozing in the sun. The new Chick Soft, Yellow, Fluffy, Wobbling on new feet. © Ziptales Pty Ltd 2008 1 ……………………………………… 3 Cinquain Cinquain (pronounced san-kane) is a form of poetry that is based on a set pattern. It has five lines and a set number of words in each line. The pattern is as follows: Line 1, one word title Line 2, two words describing the subject Line 3, three words expressing action Line 4, action line (often a group of words or phrase) Line 5, The one-word title or another word for the subject of the title. Clouds Witch Dull, oppressive, Black-clad, hunchback, Building, bruising, boiling, Cackling, mumbling, chanting, Rolling from the west, Stirring up a brew. -

Types of Poems

Types of Poems poemofquotes.com/articles/poetry_forms.php This article contains the many different poem types. These include all known (at least to my research) forms that poems may take. If you wish to read more about poetry, these articles might interest you: poetry technique and poetry definition. ABC A poem that has five lines and creates a mood, picture, or feeling. Lines 1 through 4 are made up of words, phrases or clauses while the first word of each line is in alphabetical order. Line 5 is one sentence long and begins with any letter. Acrostic Poetry that certain letters, usually the first in each line form a word or message when read in a sequence. Example: Edgar Allan Poe's "A Valentine". Article continues below... Ballad A poem that tells a story similar to a folk tale or legend which often has a repeated refrain. Read more about ballads. Ballade Poetry which has three stanzas of seven, eight or ten lines and a shorter final stanza of four or five. All stanzas end with the same one line refrain. Blank verse A poem written in unrhymed iambic pentameter and is often unobtrusive. The iambic pentameter form often resembles the rhythms of speech. Example: Alfred Tennyson's "Ulysses". Bio A poem written about one self's life, personality traits, and ambitions. Example: Jean Ingelow's "One Morning, Oh! So Early". Burlesque Poetry that treats a serious subject as humor. Example: E. E. Cummings "O Distinct". Canzone Medieval Italian lyric style poetry with five or six stanzas and a shorter ending stanza.