Studiesineducation.Pdf

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Latin America Spanish Only

Newswire.com LLC 5 Penn Plaza, 23rd Floor| New York, NY 10001 Telephone: 1 (800) 713-7278 | www.newswire.com Latin America Spanish Only Distribution to online destinations, including media and industry websites and databases, through proprietary and news agency networks (DyN and Notimex). In addition, the circuit features the following complimentary added-value services: • Posting to online services and portals. • Coverage on Newswire's media-only website and custom push email service, Newswire for Journalists, reaching 100,000 registered journalists from more than 170 countries and in more than 40 different languages. • Distribution of listed company news to financial professionals around the world via Thomson Reuters, Bloomberg and proprietary networks. Comprehensive newswire distribution to news media in 19 Central and South American countries: Argentina, Bolivia, Chile, Colombia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Domincan Republic, Ecuador, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Mexico, Nicaragua, Panama, Paraguay, Peru, Puerto Rico, Uruguay and Venezuela. Translated and distributed in Spanish. Please note that this list is intended for general information purposes and may adjust from time to time without notice. 4,028 Points Country Media Point Media Type Argentina 0223.com.ar Online Argentina Acopiadores de Córdoba Online Argentina Agensur.info (Agencia de Noticias del Mercosur) Agencies Argentina AgriTotal.com Online Argentina Alfil Newspaper Argentina Amdia blog Blog Argentina ANRed (Agencia de Noticias Redacción) Agencies Argentina Argentina Ambiental -

(OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (Inside) Interior Design

Publication Magazine Genre Frequency Language $10 DINNERS (OR LESS!) Food & Cooking English One-Off (inside) interior design review Art & Photo English Bimonthly . -

Future Publishing Statement for IPSO – April 2016

Future Publishing Statement for IPSO – April 2016 About Future Future plc is an international publishing and media group, and a leading digital company. Celebrating over 30 years in business, Future was founded in 1985 with one magazine – we now create over 200 print publications, apps, websites and events through operations in the UK, US and Australia. The company employs approximately 500 employees. Future’s leadership structure is outlined in Appendix C (the structure has changed slightly since our last statement in December 2015). Our portfolio covers consumer technology, games/entertainment, music, creative/design and photography. 48 million users globally access Future’s digital sites each month, we have over 200,000 digital subscriptions worldwide, and a combined social media audience of 20+ million followers (a list of our titles/products can be found under Appendix A). For the purpose of this statement, Future’s ‘responsible person’ is Nial Ferguson, Content Director, Media. Future’s editorial standards Through our expertise in five portfolios, Future produces engaging, informative and entertaining content to a high standard. The business is driven by a core strategy - ‘Content that Connects’ - that has been in place since 2014 (see Appendix B). This puts content at the heart of what we do, and is an approach we reiterate through staff communication. In creating content that connects, Future takes all reasonable and appropriate steps to verify what we publish. Such steps include double sourcing where necessary, and rigorous scrutiny of information and sources to ensure the accuracy of the articles we publish. Editorial process for contentious issues involves second reading by editorial. -

Category Listing March 2018

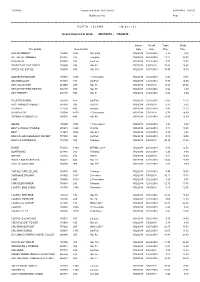

Category Listing March 2018 All Recommended Retail Prices (Inc GST), Trade (Exc GST) and/or Barcodes are subject to change at any time. G&G Title Catalogue 2/03/2018 Total Titles 2488 Count Sub Category Title Code Title Frequency RRP (inc GST) Trade ( Exc GST) Barcode Publisher 1 Adult Colouring Titles 174606 BDM POCKET SERIES Quarterly $8.99 $5.863 9772396742000 Comag Magazine Marketing NZ$ 2 Adult Colouring Titles 174387 CALM COLOUR CREATE> Bi monthly $8.99 $5.863 9772059260001 Comag Magazine Marketing NZ$ 3 Adult Colouring Titles 174360 RELAX WITH ART Monthly $7.95 $5.185 9772058811006 MARKET FORCE (UK) LTD - SEA 4 Adult Colouring Titles 174460 RELAX WITH ART HOLIDAY SPECIAL Bi monthly $13.95 $9.098 9772059059001 MARKET FORCE (UK) LTD - SEA 5 Adult Colouring Titles 174560 RELAX WITH ART PKT COLLECTION Bi monthly $9.50 $6.196 9772059058004 MARKET FORCE (UK) LTD - SEA 6 Adult Colouring Titles 174660 YOU'RE NEVER TOO GROWN UP TO Monthly $9.99 $6.515 9772059839016 Comag Magazine Marketing NZ$ 7 Agriculture 164890 BRAND Bi monthly $36.99 $24.124 9772226654008 SEYMOUR INTERNATIONAL LTD - SEA 8 Agriculture 516211 COUNTRY WIDE Monthly $12.00 $7.826 9771179985009 NZ Farm Life Media Ltd 9 Agriculture 108650 CREATIVE REVIEW Monthly $17.90 $11.674 9770262103146 MARKET FORCE (UK) LTD - SEA 10 Agriculture 109120 FARMERS WEEKLY Weekly $10.20 $6.652 9770014847908 MARKET FORCE (UK) LTD - SEA 11 Agriculture 507790 NZ LIFESTYLE BLOCK SPECIAL Annual $19.90 $12.978 9414666009122 STUFF LIMITED 12 Agriculture 508635 NZ LIFESTYLE BLOCK> Monthly $7.90 $5.152 -

Distribution List Page - 1

R56891A Gordon and Gotch (NZ) Limited 30/01/2018 8:56:53 Distribution List Page - 1 =========================================================================================================================================================== N O R T H I S L A N D ( M i d w e e k ) Issues invoiced in week 28/01/2018 - 3/02/2018 =========================================================================================================================================================== Invoice Recall Trade Retail Title Details Issue Details Date Date Price Price 2000 AD WEEKLY 105030 1025 NO. 2058 1/02/2018 12/02/2018 5.74 8.80 A/F THE AUTOMOBILE 818315 315 February 1/02/2018 26/02/2018 13.17 20.20 ADV MOTO 778879 195 Jan/Feb 1/02/2018 12/03/2018 9.78 15.00 ADVENTURE BIKE RIDER 255600 280 NO. 43 1/02/2018 5/03/2018 10.83 16.60 AFTER THE BATTLE 180480 430 NO. 178 1/02/2018 19/03/2018 10.40 15.95 AMATEUR PHOTOGR 105515 1030 11 November 1/02/2018 12/02/2018 6.98 10.70 ARCHAEOLOGY 710153 710 Jan/Feb 1/02/2018 12/03/2018 9.75 14.95 ART COLLECTOR 414050 270 NO. 83 1/02/2018 7/05/2018 16.63 25.50 ART OF KNITTING NEW ED 298470 570 NO. 95 1/02/2018 12/02/2018 6.52 9.99 ART THERAPY 298475 550 NO. 91 1/02/2018 12/02/2018 6.52 9.99 ATLANTIS RISING 726780 475 Jan/Feb 1/02/2018 12/03/2018 11.54 17.70 AUST WOMENS WEEKLY 507870 325 FEB 18 1/02/2018 5/03/2018 5.35 8.20 AUTABUY 777756 480 January 1/02/2018 26/02/2018 8.93 13.70 AUTOCAR S/F 105590 1030 15 November 1/02/2018 5/02/2018 9.78 14.99 BATMAN AUTOMOBILIA 264510 440 NO. -

Libby Magazine Titles As of January 2021

Libby Magazine Titles as of January 2021 $10 DINNERS (Or Less!) 3D World AD France (inside) interior design review 400 Calories or Less: Easy Italian AD Italia .net CSS Design Essentials 45 Years on the MR&T AD Russia ¡Hola! Cocina 47 Creative Photography & AD 安邸 ¡Hola! Especial Decoración Photoshop Projects Adega ¡Hola! Especial Viajes 4x4 magazine Adirondack Explorer ¡HOLA! FASHION 4x4 Magazine Australia Adirondack Life ¡Hola! Fashion: Especial Alta 50 Baby Knits ADMIN Network & Security Costura 50 Dream Rooms AdNews ¡Hola! Los Reyes Felipe VI y Letizia 50 Great British Locomotives Adobe Creative Cloud Book ¡Hola! Mexico 50 Greatest Mysteries in the Adobe Creative Suite Book ¡Hola! Prêt-À-Porter Universe Adobe Photoshop & Lightroom 0024 Horloges 50 Greatest SciFi Icons Workshops 3 01net 50 Photo Projects Vol 2 Adult Coloring Book: Birds of the 10 Minute Pilates 50 Things No Man Should Be World 10 Week Fat Burn: Lose a Stone Without Adult Coloring Book: Dragon 100 All-Time Greatest Comics 50+ Decorating Ideas World 100 Best Games to Play Right Now 500 Calorie Diet Complete Meal Adult Coloring Book: Ocean 100 Greatest Comedy Movies by Planner Animal Patterns Radio Times 52 Bracelets Adult Coloring Book: Stress 100 greatest moments from 100 5280 Magazine Relieving Animal Designs Volume years of the Tour De France 60 Days of Prayer 2 100 Greatest Sci-Fi Characters 60 Most Important Albums of Adult Coloring Book: Stress 100 Greatest Sci-Fi Characters Of NME's Lifetime Relieving Dolphin Patterns All Time 7 Jours Adult Coloring Book: Stress -

Magazine Titles Available Through Flipster

Magazine Titles Available Through Flipster 3D World AARP: The Magazine All About Space Allrecipes Allure America in WWII American Craft Archaeology Atlantic Backpacker Bead&Button Beanz Better Homes & Gardens Better Nutrition Bicycling Bird Watching Bloomberg Businessweek Boating Bon Appetit Brainspace Car & Driver Clean Eating Conde Nast Traveler Consumer Reports Buying Guide Cosmopolitan Country Gardens Country Living Cricket Crochet! Cruising World Diabetic Living Discover Do It Yourself Dr. Oz: The Good Life Dwell Eating Well Elle March 2020 Elle Decor Entertainment Weekly Entrepreneur Epicure Esquire Essence Family Handyman Family Tree Magazine Fast Company Field & Stream Fine Cooking Fine Gardening Fine Homebuilding Food & Travel Magazine Food & Wine Food Network Magazine Forbes Fortune Gluten-Free Living Golf Digest Good Housekeeping Good Organic Gardening GQ: Gentlemen's Quarterly Guitar Player Harper's Bazaar Harvard Health Letter Harvard Women's Health Watch Health HGTV Magazine Highlights Homes & Gardens House Beautiful In Touch Weekly InStyle Interweave Knits iPhone Life J-14 Kiplinger's Personal Finance Kiplinger's Retirement Report March 2020 Kitchens & Bathrooms Quarterly Knitscene Ladybug Lonely Planet Traveller Macworld Marie Claire (US Edition) Martha Stewart Living McCall's Quilting Men's Health Men's Journal Mindful Mother Jones Motor Trend National Geographic National Geographic Kids National Review National Wildlife (World Edition) New York Review of Books New Yorker Newsweek Global O, The Oprah Magazine Official -

Overdrive Magazine Title List, As of 11/16/2020 $10 DINNERS (OR LESS

OverDrive Magazine Title List, as of 11/16/2020 $10 DINNERS (OR LESS!) Adult Coloring Book: Stress Angels on Earth magazine (United States) Relieving Patterns (United (United States) States) 101 Bracelets, Necklaces, Animal Designs, Volume 1 and Earrings (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Stress Celebration Edition (United Relieving Patterns, Volume 2 States) 400 Calories or Less: Easy (United States) Italian (United States) Animal Tales (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Stress 50 Greatest Mysteries in the Antique Trader (United Relieving Peacocks (United Universe (United States) States) States) 52 Bracelets (United States) Aperture (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Stress 5280 Magazine (United Relieving Tropical Travel Apple Magazine (United States) Patterns (United States) States) 60 Days of Prayer (United Adweek (United States) Arabian Horse World (United States) States) Aero Magazine International Adirondack Explorer (United (United States) Arc (United States) States) AFAR (United States) ARCHAEOLOGY (United Adirondack Life (United States) Air & Space (United States) States) Architectural Digest (United Airways Magazine (United ADMIN Network & Security States) States) (United States) Art Nouveau Birds: A Stress All-Star Electric Trains Adult Coloring Book: Birds of Relieving Adult Coloring Book (United States) the World (United States) (United States) Allure (United States) Adult Coloring Book: Dragon Artists Magazine (United World (United States) America's Civil War (United States) States) Adult Coloring Book: Ocean ASPIRE -

Channel Changers Meg Morrison and Four Other Grads Redefine the Tv Career

people technology innovation v9.2 2016 $4.95 techlifemag.ca RINGSIDE FOR THE FINAL MOMENTS OF LIFE AS A PRO WRESTLER CHANNEL CHANGERS MEG MORRISON AND FOUR OTHER GRADS REDEFINE THE TV CAREER HOW TO SEE CANADA BY BICYCLE NAIT BAKERS GO FOR GOLD IN PARIS THE FINE ART OF THE TRADES P. 26 + UNCONDITIONAL CRITTER CARE P. 30 A LIFETIME OF GIVING Sylvia Krikun (Medical X-ray Technology ‘68) and husband Mickey took their passion to help others to the small town they loved. Leaders in their community, the Krikuns made an impact by selflessly volunteering for decades. Seeing other family members also benefit from NAIT, Sylvia plans to include the institution as a beneficiary in her will. Read more about the Krikuns’ inspirational story and how you can leave a legacy of generosity at nait.ca/giving FIELD SPECIALISTS AND MAINTENANCE TECHNICIANS Who are we? We are the world’s largest oilfield services company1. Working globally—often in remote and challenging locations—we invent, design, engineer, and apply technology to help our customers find and produce oil and gas safely. Who are we looking for? We’re looking for high-energy, motivated individuals who want to begin careers as Field Specialists or Maintenance Technicians. In these positions, years of you’ll apply your technical expertise and troubleshooting skills to ensure quality service delivery. n Do you want a high level of responsibility early and the opportunity 85 to make a real difference on the job? n Are you interested in an unusual career with a sense of adventure? innovation n Do you hold an associate’s degree or diploma in a relevant technical discipline or have equivalent formal military training? >120,000 employees If the answer is yes, apply for a position as a Maintenance >140 nationalities Technician or Field Specialist. -

Net Amazing Wellness 3D Artist America in WWII 3D Worl

FLIPSTER TITLE LIST Updated July 2019 .net Amazing Wellness 3D Artist America in WWII 3D World American Art Collector 5 Ingredients 15 Minutes American Craft 50 United States Coloring Book American Girl 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens American History Workbook AARP Bulletin The American Poetry Review AARP: The Magazine American Presidents - The Leaders of History's Greatest Nation Coloring & Activity Book ABC-123 Learn My Letter & Numbers American Scientist Really Big Coloring Book Adult Coloring Book: Doodle American Survival Guide Inspirations Adult Coloring Book: Stress Relieving American Theatre Ocean Animal Patterns Adult Coloring Book: Stress Relieving Animal Tales Paisley Patterns Adult Coloring Book: Stress Relieving Animation Patterns Adult Coloring Book: Stress Relieving AppleMagazine Patterns Volume 2 Adult Coloring Book: Stress Relieving Architectural Digest Tropical Travel Patterns All About History Aromatherapy Thymes All About Space Artist's Back to Basics Allure Artist's Drawing & Inspiration Alternative Medicine Magazine The Artist's Magazine Amateur Photographer Artist's Palette Ask Black Belt Ask Teacher's Guide Black Enterprise Astronomy Black EOE Journal The Atlantic Bloomberg Businessweek Automobile Magazine Boating Babybug Bon Appetit Back Stage Boys' Life Baseball Digest Brain World Basketball Times Brainspace BBC Good Food Bride & Groom Bead&Button Brides Beadwork Butterflies & Birds Really Big Coloring Book Better Homes & Gardens Cake Decorating Heaven Better Nutrition Cake Decoration & Sugarcraft Bicycling -

Interior Design Review Every Other Month Magazine SU

Title Frequency if provided Format Lending Model (inside) interior design review Every other month Magazine SU ¡Hola! Especial Viajes Twice per year Magazine SU ¡HOLA! FASHION Monthly Magazine SU ¡Hola! Fashion: Especial Alta Costura Twice per year Magazine SU ¡Hola! Mexico Every other week Magazine SU 0024 Horloges Twice per year Magazine SU 01net Every other week Magazine SU 11 Freunde Monthly Magazine SU 220 Triathlon Monthly Magazine SU 24H Brasil Weekly Magazine SU 25 Beautiful Homes Monthly Magazine SU 2nd セカンド Monthly Magazine SU 3D World Monthly Magazine SU 4x4 magazine Every other month Magazine SU 4x4 Magazine Australia Monthly Magazine SU 5280 Magazine Monthly Magazine SU 60 Days of Prayer Every other month Magazine SU 7 Jours Weekly Magazine SU 7 TV-Dage Weekly Magazine SU a+u Architecture and Urbanism Monthly Magazine SU ABC Organic Gardener Magazine Every other month Magazine SU ABC 互動英語 Monthly Magazine SU Accion Cine-Video Monthly Magazine SU AD (D) Monthly Magazine SU AD España Monthly Magazine SU AD France Every other month Magazine SU AD Italia Monthly Magazine SU AD Russia Monthly Magazine SU AD 安邸 Monthly Magazine SU Adega Monthly Magazine SU Adirondack Explorer Every other month Magazine SU Adirondack Life Monthly Magazine SU ADMIN Network & Security Every other month Magazine SU AdNews Every other month Magazine SU Advanced 彭蒙惠英語 Monthly Magazine SU Adventure Magazine Every other month Magazine SU Adweek Weekly Magazine SU AERO Magazine Monthly Magazine SU AERO Magazine América Latina Every other month Magazine SU -

FLIPSTER TITLES April 2018 .Net 3D Artist 3D World 5 Ingredients 15

FLIPSTER TITLES .net AppleMagazine April 2018 3D Artist Architectural Digest 3D World Artist's Back to Basics 5 Ingredients 15 Minutes Artist's Drawing & Inspiration 50 United States Coloring Book Artist's Palette 7 Habits of Highly Effective Teens Workbook Ask AARP Bulletin Ask Teacher's Guide AARP: The Magazine The Atlantic ABC-123 Learn My Letter & Numbers Really Big Automobile Magazine Coloring Book Babybug Adult Coloring Book: Doodle Inspirations Baseball Digest Adult Coloring Book: Stress Relieving Ocean Basketball Times Animal Patterns BBC Good Food Adult Coloring Book: Stress Relieving Paisley Patterns Bead&Button Adult Coloring Book: Stress Relieving Patterns Beadwork Adult Coloring Book: Stress Relieving Patterns Better Homes & Gardens Volume 2 Better Nutrition Adult Coloring Book: Stress Relieving Tropical Travel Patterns Bicycling Allure Bird Watcher's Digest Alternative Medicine Magazine Bird Watching Amateur Photographer Birds & Blooms Amazing Wellness Bitch Magazine: Feminist Response to Pop Culture American Art Collector Black Beauty & Hair American Craft Black Belt The American Poetry Review Black Enterprise American Presidents - The Leaders of History's Greatest Nation Coloring & Activity Book Bloomberg Businessweek American Survival Guide Boating Animation Bon Appetit Boys' Life Brain World Color, Cut & Fold Sugar Skulls Brainspace Columbia Journalism Review Bride & Groom Comics & Gaming Magazine Brides Communication Arts Butterflies & Birds Really Big Coloring Book Computer Music Cake Decorating Heaven Conde Nast Traveler