Human Rights Issues in Constitutional Courts: Why Amici Curiae Are Important in the U.S., and What Australia Can Learn from the U.S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commission's Submission

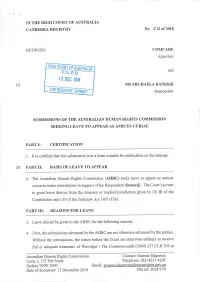

IN THE HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA CANBERRA REGISTRY No. C12 of 2018 BETWEEN: COMCARE Appellant HIGH COURT OF AUSTRALIA and FILED 12 DEC 2018 10 MS MICHAELA BANERTI THE REGISTRY SYDNEY Respondent SUBMISSIONS OF THE AUSTRALIAN HUMAN RIGHTS COMMISSION SEEKING LEAVE TO APPEAR AS AMICUS CURIAE PART I: CERTIFICATION 1. It is certified that this submission is in a form suitable for publication on the internet. 20 PART II: BASIS OF LEAVE TO APPEAR 2. The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) seeks leave to appear as amicus curiae to make submissions in support of the Respondent (Banerji). The Court's power to grant leave derives from the inherent or implied jurisdiction given by Ch III of the Constitution and s 30 of the Judiciary Act 1903 (Cth). PART III: REASONS FOR LEAVE 3. Leave should be given to the AHRC for the following reasons. 4. First, the submissions advanced by the AHRC are not otherwise advanced by the parties. Without the submissions, the issues before the Court are otherwise unlikely to receive full or adequate treatment: cf Wurridjal v The Commonwealth (2009) 237 CLR 309 at Australian Human Rights Commission Contact: Graeme Edgerton Level 3, 175 Pitt Street Telephone: (02) 8231 4205 Sydney NSW 2000 Email: [email protected] Date of document: 12 December 2018 File ref: 2018/179 -2- 312-3. The Commission’s submissions aim to assist the Court in a way that it may not otherwise be assisted: Levy v State of Victoria (1997) 189 CLR 579 at 604 (Brennan CJ). 5. Secondly, the proposed submissions are brief and limited in scope. -

Colette Langos* & Paul Babie**

SOCIAL MEDIA, FREE SPEECH AND RELIGIOUS FREEDOM Colette Langos* & Paul Babie** INTRODUCTION Social media forms part of the fabric of 21st century global life. People the world over use it to disseminate any number of ideas, views, and anything else, ranging from the benign to the truly malign.1 One commentator even diagnoses its ubiquity as a disease, and prescribes remedies for individual users and society as a whole.2 Yet, despite such concerns, little direct governmental regulation exists to control the power of social media to spread ideas and messages. To date, this responsibility has fallen largely on social media platform providers themselves, with the inevitable outcome being a disparate patchwork of approaches driven more by corporate expediency and the corresponding profit motive than a rational comprehensive policy integrated at the national and international levels.3 What little governmental control there is comes either * Senior Lecturer in Law, Adelaide Law School, The University of Adelaide. ** Adelaide Law School Professor of the Theory and Law of Property, The University of Adelaide. 1 See GLENN HARLAN REYNOLDS, THE SOCIAL MEDIA UPHEAVAL at 1, 38, 63 (Encounter Books 2019); SARAH T. ROBERTS, BEHIND THE SCREEN CONTENT MODERATION IN THE SHADOWS OF SOCIAL MEDIA at 33-35 (Yale Univ. Press 2019). 2 Reynolds, supra note 1, at 7, 63. 3 See Sofia Grafanaki, Platforms, the First Amendment and Online Speech: Regulating the Filters, 39 PACE L. REV. 111, 147 (2018); Eugene Volokh, Government-Run Fora on Private Platforms, in the @RealDonaldTrump User Blocking Controversy, THE VOLOKH CONSPIRACY (July 9, 2019, 3:09 PM), https://reason.com/2019/07/09/government-run-fora-on-private-platforms-in-the- realdonaldtrump-user-blocking-controversy/; Fiona R. -

PRIVATE RIGHTS, PROTEST and PLACE in BROWN V TASMANIA

PRIVATE RIGHTS, PROTEST AND PLACE IN BROWN v TASMANIA PATRICK EMERTON AND MARIA O’SULLIVAN* I INTRODUCTION Protest is an important means of political communication in a contemporary democracy. Indeed, a person’s right to protest goes to the heart of the relationship between an individual and the state. In this regard, protest is about power. On one hand, there is the power of individuals to act individually or a collective to communicate their concerns about the operation of governmental policies or business activities. On the other, the often much stronger power wielded by a state to restrict that communication in the public interest. As part of this, state authorities may seek to limit certain protest activities on the basis that they are disruptive to public or commercial interests. The question is how the law should reconcile these competing interests. In this paper, we recognise that place is often integral to protest, particularly environmental protest. In many cases, place will be inextricably linked to the capacity of protest to result in influence. This is important given that the central aim of protest is usually to be an agent of change. As a result, the purpose of any legislation which seeks to protect business activities from harm and disruption goes to the heart of contestations about protest and power. In a recent analysis of First Amendment jurisprudence, Seidman suggests that [t]here is an intrinsic relationship between the right to speak and the ownership of places and things. Speech must occur somewhere and, under modern conditions, must use some things for purposes of amplification. -

Before the High Court

Before the High Court Comcare v Banerji: Public Servants and Political Communication Kieran Pender* Abstract In March 2019 the High Court of Australia will, for the first time, consider the constitutionality of limitations on the political expression of public servants. Comcare v Banerji will shape the Commonwealth of Australia’s regulation of its 240 000 public servants and indirectly impact state and local government employees, cumulatively constituting 16 per cent of the Australian workforce. But the litigation’s importance goes beyond its substantive outcome. In Comcare v Banerji, the High Court must determine the appropriate methodology to apply when considering the implied freedom of political communication’s operation on administrative decisions. The approach it adopts could have a significant impact on the continuing development of implied freedom jurisprudence, as well as the political expression of public servants. I Introduction Australian public servants have long endured an ‘obligation of silence’.1 Colonial civil servants were subject to strict limitations on their ability to engage in political life.2 Following Federation, employees of the new Commonwealth of Australia were not permitted to ‘discuss or in any way promote political movements’.3 While the more draconian of these restrictions have been gradually eased, limitations remain on the political expression of public servants. Until now, these have received surprisingly little judicial scrutiny. Although one of the few judgments in this field invalidated the impugned regulation,4 the Australian Public Service (‘APS’) has continued to limit the speech of its employees. * BA (Hons) LLB (Hons) (ANU); Legal Advisor, Legal Policy & Research Unit, International Bar Association, London, England. -

The High Court on Constitutional Law: the 2019 Statistics

1226 UNSW Law Journal Volume 43(4) THE HIGH COURT ON CONSTITUTIONAL LAW: THE 2019 STATISTICS ANDREW LYNCH* This article presents data on the High Court’s decision-making in 2019, examining institutional and individual levels of unanimity, concurrence and dissent. It points out distinctive features of those decisions – noting particularly the high frequency of both seven- member benches and the number of cases decided by concurrence over 2019. The latter suggests the possibility of greater judicial individualism re-emerging on the Court despite the clear endorsement of the ‘collegiate approach’ by Chief Justice Kiefel and its practice in the first two years of her tenure as the Chief Justice. This article is the latest instalment in a series of annual studies conducted by the authors since 2003. I INTRODUCTION This article reports the way in which the High Court as an institution and its individual judges decided the matters that came before them in 2019. It continues a series which began in 2003.1 The High Court’s decisions and the subset of constitutional matters decided in the calendar year are tallied to reveal how the institution has responded to the cases that came before it and where each individual member of the Court sits within those institutional decisions. The purpose of these articles is to provide the reader with the level of consensus, including the degree to which this is unanimous or fragmented, and dissent, and also the relative rates of joining by individual Justices in the same set of reasons for judgment. The latter can indicate the existence of regular coalitions on the bench. -

The Sydney Law Review

volume 42 number 4 december 2020 the sydney law review articles Dignity and the Australian Constitution – Scott Stephenson 369 Three Recent Royal Commissions: The Failure to Prevent Harms and Attributions of Organisational Liability – Penny Crofts 395 The Hidden Sexual Offence: The (Mis)Information of Fraudulent Sex Criminalisation in Australian Universities – Jianlin Chen 425 review essays Judging the New by the Old in the Judicial Review of Executive Action – Stephen Gageler AC 469 Pioneers, Consolidators and Iconoclasts of Tort Law – Barbara McDonald 483 EDITORIAL BOARD Elisa Arcioni (Editor) Kristin Macintosh Celeste Black (Editor) Tanya Mitchell Ben Chen Michael Sevel Emily Hammond Belinda Smith Jason Harris Yane Svetiev Ghena Krayem Kimberlee Weatherall STUDENT EDITORIAL COMMITTEE Margery Ai Mischa Davenport Thomas Dickinson Jessica Bi Matthew Del Gigante Oliver Hanrahan Sydney Colussi Thomas Dews Alice Strauss Before the High Court Editor: Emily Hammond Book Review Editor: Yane Svetiev Publishing Manager: Cate Stewart Correspondence should be addressed to: Sydney Law Review Sydney Law School Building F10, Eastern Avenue UNIVERSITY OF SYDNEY NSW 2006 AUSTRALIA Email: [email protected] Website and submissions: <https://sydney.edu.au/law/our- research/publications/sydney-law-review.html> For hardcopy subscriptions outside North America: [email protected] For hardcopy subscriptions in North America: [email protected] The Sydney Law Review is a refereed journal. © 2020 Sydney Law Review and authors. ISSN 0082–0512 (PRINT) ISSN 1444–9528 (ONLINE) Dignity and the Australian Constitution Scott Stephenson Abstract Today dignity is one of the most significant constitutional principles across the world given that it underpins and informs the interpretation of human rights. -

1 Implied Freedom of Political Communication

1 Implied freedom of Political Communication – development of the test and tools Chris Bleby 1. The implied freedom of political communication was first announced in Nationwide News v Wills1 and Australian Capital Television Pty Ltd v The Commonwealth.2 As Brennan J described the freedom at this nascent stage:3 “the legislative powers of the Parliament are so limited by implication as to preclude the making of a law trenching upon that freedom of discussion of political and economic matters which is essential to sustain the system of representative government prescribed by the Constitution.” 2. ACTV concerned Part IIID of the Broadcasting Act 1942 (Cth), which was introduced by the Political Broadcasts and Political Disclosures Act 1991 (Cth). It contained various prohibitions, with exemptions, on broadcasting on behalf of the Commonwealth government in an election period, and prohibited a broadcaster from broadcasting a “political advertisement” on behalf of a person other than a government or government authority or on their own behalf. 3. Chief Justice Mason’s judgment remains the starting point of the implied freedom for its analysis based in ss 7 and 24 of the Constitution. His Honour also ventured a test to be applied for when the implied freedom could be said to be infringed. This was a lengthy, descriptive test. Critically, he observed that the freedom was only one element of a society controlled by law:4 Hence, the concept of freedom of communication is not an absolute. The guarantee does not postulate that the freedom must always and necessarily prevail over competing interests of the public. -

Implied Freedom of Communication in Australia

The Rule of Law and the Implied Freedom of Communication in Australia Magna Carta 1215 “[the] right of free speech is one which it is for the public interest that individuals should possess, and indeed that they should exercise it without impediment, so long as no wrongful act is done.” No free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned, or disseised, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any other way ruined, nor will we go against him Lord Coleridge in Bonnard v Perryman [1891] 2 Ch 269, 284) or send against him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the “the end of law is not to abolish or restrain, but to preserve and enlarge freedom. For in all the states of created land. [39] beings, capable of laws, where there is no law there is no freedom.” John Locke, Two Treatises of Government (1689) Preamble of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights (1948): ‘To sustain a representative democracy embodying the principles prescribed by the Constitution, freedom of public discussion of political and economic matters is essential’ Brennan J in Nationwide News Pty Ltd v Wills [1992] HCA 46 ‘it is essential, if man is not to be compelled to have ‘...ss 7 and 24 and the related sections of the Constitution necessarily protect that freedom of recourse, as a last resort, to communication between the people concerning political or government matters which enables rebellion against tyranny the people to exercise a free and informed choice as electors.’ and oppression, that human rights should be Brennan CJ, Dawson, Toohey, Gaudron, McHugh, Gummow and Kirby JJ in Lange v Australian Broadcasting Corporation protected by the rule [1997] HCA 25 of law.’ ‘One might wish for more rationality, less superficiality, diminished invective and increased logic and persuasion in political discourse. -

VICTORIAN BAR NEWS WINTER 2021 ISSUE 169 WINTER 2021 VICTORIAN BAR Editorial

169 VICTORIAN BAR NEWS BAR VICTORIAN ISSUE 169 WINTER 2021 Sexual The Annual Bar VICTORIAN Harassment: Dinner is back! It’s still happening BAR By Rachel Doyle SC NEWS WINTER 2021 169 Plus: Vale Peter Heerey AM QC, founder of Bar News ISSUE 169 WINTER 2021 VICTORIAN BAR editorial NEWS 50 Evidence law and the mess we Editorial are in GEOFFREY GIBSON Not wasting a moment 5 54 Amending the national anthem of our freedoms —from words of exclusion THE EDITORS to inclusion: An interview with Letters to the Editors 7 the Hon Peter Vickery QC President’s message 10 ARNOLD DIX We are Australia’s only specialist broker CHRISTOPHER BLANDEN 60 2021 National Conference Finance tailored RE-EMERGE 2021 for lawyers. With access to all major lenders Around Town and private banks, we’ll secure the best The 2021 Victorian Bar Dinner 12 Introspectives JUSTIN WHEELAHAN for legal professionals home loan tailored for you. 12 62 Choices ASHLEY HALPHEN Surviving the pandemic— 16 64 Learning to Fail JOHN HEARD Lorne hosts the Criminal Bar CAMPBELL THOMSON 68 International arbitration during Covid-19 MATTHEW HARVEY 2021 Victorian Bar Pro 18 Bono Awards Ceremony 70 My close encounters with Nobel CHRISTOPHER LUM AND Prize winners GRAHAM ROBERTSON CHARLIE MORSHEAD 72 An encounter with an elected judge Moving Pictures: Shaun Gladwell’s 20 in the Deep South portrait of Allan Myers AC QC ROBERT LARKINS SIOBHAN RYAN Bar Lore Ful Page Ad Readers’ Digest 23 TEMPLE SAVILLE, HADI MAZLOUM 74 No Greater Love: James Gilbert AND VERONICA HOLT Mann – Bar Roll 333 34 BY JOSEPH SANTAMARIA -

Human Rights Issues in Constitutional Courts: Why Amici Curiae Are Important in the U.S., and What Australia Can Learn from the U.S

Received: June 5 May, Date of acceptance: September 25, 2020, Date of publication: November 30 2020, DOI: https://doi.org/10.26826/law-in-context.v37i1.127 Human Rights Issues in Constitutional Courts: Why Amici Curiae are Important in the U.S., and What Australia Can Learn from the U.S. Experience By H. W. Perry Jr1, University Distinguished Teaching Professor, Associate Professor of Law, Associate Professor of Government at The University of Texas at Austin, Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2947-8668 and Patrick Keyzer2, Research Professor of Law and Public Policy at La Trobe University, Orcid: https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0807-8366 1 The University of Texas at Austin, USA 2 La Trobe University ABSTRACT Unlike thirty years ago, human rights issues are now routinely raised in Australian constitutional cases. In this ar- ticle, the authors examine the role of the amicus curiae in the United States Supreme Court and consider how far and to what extent the amicus curiae device has been accepted in decisions of the High Court of Australia. The authors analyse the High Court’s treatment of applications for admissions as amici curiae, noting the divergent approaches - plicants who seek admission to make oral submissions. Human rights cases raise questions of minority rights that shouldtaken by not Chief be adjudicated Justice Brennan without and input Justice from Kirby, those and minorities. drawing attentionThe authors to therecommend practical thatdifficulties Australia faced adopt by apthe U.S. approach, to admit written submissions as a matter of course, and to allow applicants to make oral submissions establishing legal policy norms for the entire nation, including for the identity groups that increasingly occupy the Court’swhen they attention. -

Silencing the Sovereign People*

SILENCING THE SOVEREIGN PEOPLE* P A Keane† Colleagues, ladies and gentlemen, May I say how honoured I am to have been asked to deliver this year's Spigelman Oration. It was my great good fortune to appear on several occasions on the same side as Jim Spigelman in the High Court when he was a de facto Solicitor-General for New South Wales in the 1990s. Mr Spigelman QC was one of the most compelling advocates of his time. His colleagues from the other States were in awe of him. Honesty compels me to say, however, that I cannot recall that the deployment of his formidable skills as an advocate in the interests of the States ever resulted in our actually winning any cases. Jim's efforts did, however, inspire the rest of our tatterdemalion little band with a deep and abiding admiration for his intellectual depth and acuity as a lawyer as well as his skills as an advocate. Later, I came to value, even more highly, the intellectual leadership that he brought as Chief Justice of New South Wales to the resolution of the problems that challenged the administration of criminal justice at around the turn of the century in relation to the revelations of sexual abuse of children in both domestic and institutional settings. His leadership of the Court of Criminal Appeal helped to ensure that the legacies in our criminal law of the inveterate misogyny of the great sages of the common law were not allowed to prevent dark crimes committed in secret against children from being brought to justice. -

Regulating Truth and Lies in Political Advertising: Implied Freedom Considerations

REGULATING TRUTH AND LIES IN POLITICAL ADVERTISING: IMPLIED FREEDOM CONSIDERATIONS KIERAN PENDER* ABSTRACT Contemporary politics is increasingly described as ‘post-truth’. In Australia and elsewhere, misleading or false statements are being deployed in electoral campaigning, with troubling democratic consequences. Presently, two Australian jurisdictions have laws that require truth in political advertising; there have been proposals for such regulation in several more, including at a federal level. This Article considers whether these laws are consistent with the implied freedom of political communication in the Constitution. It suggests that the existing provisions, in South Australia (SA) and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), would likely satisfy the proportionality test currently favoured by the High Court. However, the Article identifies several implied freedom concerns which could prevent more onerous limitations on misleading political campaigning. Legislatures therefore find themselves between a rock and a hard place: minimalistic regulation may be insufficient to curtail the rise of electoral misinformation, while more robust laws risk invalidity. I INTRODUCTION [T]he deliberate falsehood and the outright lie used as legitimate means to achieve political ends, have been with us since the beginning of recorded history. Truthfulness has never been counted among the political virtues – Hannah Arendt1 There is no human right to disseminate information that is not true – Lord Hobhouse2 Navigating the streets of Canberra in 2020, an observant driver might have spotted an advertisement from The Australia Institute (TAI), a progressive think-tank, on the side of a parked van. In bold font, it observed: ‘It’s perfectly legal to lie in a political ad and it shouldn’t be.