Represent!: Hip-Hop and the Self-Aesthetic Relation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Claimed Studios Self Reliance Music 779

I / * A~V &-2'5:~J~)0 BART CLAHI I.t PT. BT I5'HER "'XEAXBKRS A%9 . AFi&Lkz.TKB 'GMIG'GCIKXIKS 'I . K IUOF IH I tt J It, I I" I, I ,I I I 681 P U B L I S H E R P1NK FLOWER MUS1C PINK FOLDER MUSIC PUBLISH1NG PINK GARDENIA MUSIC PINK HAT MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PINK 1NK MUSIC PINK 1S MELON PUBL1SHING PINK LAVA PINK LION MUSIC PINK NOTES MUS1C PUBLISHING PINK PANNA MUSIC PUBLISHING P1NK PANTHER MUSIC PINK PASSION MUZICK PINK PEN PUBLISHZNG PINK PET MUSIC PINK PLANET PINK POCKETS PUBLISHING PINK RAMBLER MUSIC PINK REVOLVER PINK ROCK PINK SAFFIRE MUSIC PINK SHOES PRODUCTIONS PINK SLIP PUBLISHING PINK SOUNDS MUSIC PINK SUEDE MUSIC PINK SUGAR PINK TENNiS SHOES PRODUCTIONS PiNK TOWEL MUSIC PINK TOWER MUSIC PINK TRAX PINKARD AND PZNKARD MUSIC PINKER TONES PINKKITTI PUBLISH1NG PINKKNEE PUBLISH1NG COMPANY PINKY AND THE BRI MUSIC PINKY FOR THE MINGE PINKY TOES MUSIC P1NKY UNDERGROUND PINKYS PLAYHOUSE PZNN PEAT PRODUCTIONS PINNA PUBLISHING PINNACLE HDUSE PUBLISHING PINOT AURORA PINPOINT HITS PINS AND NEEDLES 1N COGNITO PINSPOTTER MUSIC ZNC PZNSTR1PE CRAWDADDY MUSIC PINT PUBLISHING PINTCH HARD PUBLISHING PINTERNET PUBLZSH1NG P1NTOLOGY PUBLISHING PZO MUSIC PUBLISHING CO PION PIONEER ARTISTS MUSIC P10TR BAL MUSIC PIOUS PUBLISHING PIP'S PUBLISHING PIPCOE MUSIC PIPE DREAMER PUBLISHING PIPE MANIC P1PE MUSIC INTERNATIONAL PIPE OF LIFE PUBLISHING P1PE PICTURES PUBLISHING 882 P U B L I S H E R PIPERMAN PUBLISHING P1PEY MIPEY PUBLISHING CO PIPFIRD MUSIC PIPIN HOT PIRANA NIGAHS MUSIC PIRANAHS ON WAX PIRANHA NOSE PUBL1SHING P1RATA MUSIC PIRHANA GIRL PRODUCTIONS PIRiN -

Cathy Grier & the Troublemakers I'm All Burn CG

ad - funky biscuit … Frank Bang | Crazy Uncle Mikes Photo: Chris Schmitt 4 | www.SFLMusic.com 6 | www.SFLMusic.com Turnstiles | The Funky Biscuit Photo: Jay Skolnick Oct/Nov 2020 4. FRANK BANG 8. MONDAY JAM Issue #97 10. KEVIN BURT PUBLISHERS Jay Skolnick 12. DAYRIDE RITUAL [email protected] 18. VANESSA COLLIER Gary Skolnick [email protected] 22. SAMANTHA RUSSELL BAND EDITOR IN CHIEF Sean McCloskey 24. RED VOODOO [email protected] 28. CATHY GRIER SENIOR EDITOR Todd McFliker 30. LISA MANN [email protected] DISTRIBUTION MANAGER 32. LAURA GREEN Gary Skolnick [email protected] 34. MUSIC & COVID OPERATIONS MAGAGER 48. MONTE MELNICK Jessica Delgadillo [email protected] 56. TYLER BRYANT & THE SHAKEDOWN ADVERTISING [email protected] 60. SOCIALLY RESPONSIBLE FUN CONTRIBUTORS 62. THE REIS BROTHERS Brad Stevens Ray Anton • Debbie Brautman Message to our readers and advertisers Lori Smerilson Carson • Tom Craig Jessie Finkelstein As SFL Music Magazine adjusts to the events transpiring over the last several Peter “Blewzzman” Lauro weeks we have decided to put out the April issue, online only. We believe that Alex Liscio • Janine Mangini there is a need to continue to communicate what is happening in the music Audrey Michelle • Larry Marano community we love so dearly and want to be here for all of you, our readers Romy Santos • David Shaw and fellow concert goers and live music attendees, musicians, venues, clubs, Darla Skolnick and all the people who make the music industry what it is. SFL is dependent on its advertisers to bring you our “in print” all music maga- COVER PHOTO zine here in South Florida every month. -

Peasant Identities in Russia's Turmoil

PEASANT IDENTITIES IN RUSSIA’S TURMOIL: STATUS, GENDER, AND ETHNICITY IN VIATKA PROVINCE, 1914-1921 DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Aaron Benyamin Retish, M.A. The Ohio State University, 2003 Dissertation Committee: Approved by Professor David Hoffmann, Adviser Professor Eve Levin _________________ Professor Nicholas Breyfogle Adviser Department of History Copyright by Aaron Benyamin Retish 2003 ABSTRACT From 1914-21, the Russian countryside underwent an enormous social and political transformation. World War I and civil war led to conscription into the tsarist, Bolshevik, and anti-Bolshevik armies, removing over fourteen million young male peasants from their villages. Revolution destroyed the centuries-old peasant-landlord relationship, redistributed land among the peasantry, democratized the countryside, and allowed villages to install autonomous governing bodies. War and social turmoil also brought massive famine and government requisitioning of grain and possessions, killing thousands of peasants and destroying their means of existence. The Bolshevik victory, a defining event of the twentieth century, was ultimately determined by the temporary support of the peasantry, the vast majority of Russia's population. This project studies the interaction between peasants and government in the Russian province of Viatka from the beginning of World War I to the end of the Civil War in 1921. In doing so, it will advance how scholars understand the nature of the Revolution, peasant-state relations, and peasant society and culture in general. On the ii one hand, I analyze Russia’s changes through a study of peasant responses to tsarist, Provisional Government, and Soviet recruitment into the armed forces; requisitioning of grain and possessions; and establishment of local administrations. -

Mul Timedia Superstores Have It

$5.50 (U.S.), $6.50 (CAN.), £4.50 (U.K.) IN MUSIC NEWS Estefan $S» CCVR ******XM 3 -DIGIT 908 SGEE4EM740M09907441 002 0675 000 BI MAR 2396 1 03 Epic Set MONTY GREENLY 3740 ELM AVE APT A LONG BEACH, CA 90807 -3402 Opens Doors To Variety Of Sounds 1 SEE PAGE 10 THE INTERNATIONAL NEWSWEEKLY OF MUSIC, VIDEO AND HOME ENTERTAINMENT SEPTEMBER 2, 1995 ADVERTISEMENTS Mul timedia Superstores Have It All RCA's McBride Book /Music Giants The New Rage In Retail Banks On `Angels' BY ED CHRISTMAN Borders Books & Music, which has mu- departments can be found in many in- BY DEBORAH EVANS PRICE sic in 69 of its 90 superstores, and New dependent bookstores around the NEW YORK -A plethora of retail York -based Barnes & Noble, which has country. NASHVILLE -In the wake of chains has decided to embrace book music departments in approximately 60 Among music chains, the Minneapo- her successful sophomore album, "The Way That I Am," RCA has .3 Barnes (;,Noble,,,, BORDERS* Booksellers Since /873 hás;tings Philip Anselmo. Pepper Keenan. Kirk Windstein. Todd Strange. Jimmy Bower and music superstores as the shopping of its 280 superstores. In addition, Flo- lis -based Musicland Group has been environments of the future. rence, Ala. -based Books -A- Million and racing to build giant Media Play outlets McBRIDE Ì Over the last three years, at least two Atlanta -based Waterstone's are exper- and small-town On Cue stores; both are major book chains have added music, imenting with music in some of their multimedia stores that have music and high expectations for Martina The album featuring video, and other home entertainment stores. -

Djat/MUSICA Gum/CAPITOL KONTROLL

die österreichischen Club- & Dancecharts KW 09/10/2004 K O N T R O L L - L I S T E Plz LW WoC Title Artist Label/Distribution PP 1 ➔ 1 8 Get Busy GAMBAS & ALVARO DJat/MUSICA 1 2 ▲ 3 8 Just A Little More Love DAVID GUETTA Gum/CAPITOL 1 3 ▲ NEW 0 Alive STARSPLASH Kontor/EDEL 3 4 ▲ 9 8 Kill The Silence LICHTENFELS Club Cult./WARNER 2 5 ▲ 13 10 Traffic DJ TIESTO Magic Muzik/IMPORT 5 6 ▼ 4 6 Pretty Green Eyes ULTRABEAT Kontor/EDEL 4 7 ➔ 7 6 Silence EP GIGI D’AGOSTINO Media Records/ECHO ZYX 4 8 ▲ 28 6 Are Am Eye 2.3 COMMANDER TOM A45/EDEL 8 9 ▼ 2 4 Geschwindigkeitsrausch ZIGGY X Aqualoop/IMPORT 2 10 ▲ NEW 0 Wir Brauchen Bass DICKHEADZ Mental Madness/n.a. 10 11 ▲ 18 2 Nobody (Likes The Record That I Play) DJ TOCADISCO Superstar/WARNER 11 12 ▲ 40 4 Freaks MOGUAI Superstar/WARNER 12 13 ▼ 10 10 Gipsy GIPSY Polo/IMPORT 8 14 ▲ NEW 0 Words MARK’ OH FT. TJERK Orbit/SONY MUSIC 14 15 ▲ 27 6 Music & You ROOM 5 ft. OLIVER CHEATHAM Noise Traxx/PIAS/MUSICA 15 16 ▼ 15 10 Jigga Jigga! SCOOTER Sheffield Tunes/EDEL 3 17 ▲ 22 4 Surrender LASGO EMI/CAPITOL 16 18 ▼ 12 2 Sun Comes Out PHATS & SMALL BMG ARIOLA 12 19 ▼ 6 8 Ballet Dancer MASTER BLASTER vs. TURBO B. Clubland/SONY MUSIC 4 20 ▼ 14 2 Knockin´ 2004 SILICON BROTHERS FEAT. PAMELA N´JOY/EDEL 14 Plz LW WoC Title Artist Label/Distribution Plz Title Artist Label/Distribution 21 ▲ NEW 0 Gonna Make You Sweat OLIVER MOLDAN Superstar/WARNER 61 Funk That ARMANI & GHOST Byte/IMPORT 22 ▲ 23 2 The Nighttrain KADOC Dos Or Die/IMPORT 62 The Sun Always Shines On TV MILK INC. -

Tony's Itunes Library

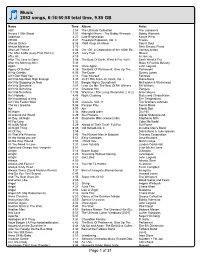

Music 2053 songs, 6:16:50:58 total time, 9.85 GB Name Time Album Artist ABC 2:54 The Ultimate Collection The Jackson 5 Across 110th Street 3:51 Midnight Mover - The Bobby Womack ... Bobby Womack Addiction 4:27 Late Registration Kanye West AEIOU 8:41 Freestyle Explosion, Vol. 3 Freeze African Dance 6:08 1989 Keep On Movin' Soul II Soul African Mailman 3:10 Nina Simone Piano Afro Loft Theme 6:06 Om 100: A Celebration of the 100th Re... Various Artists The After 6 Mix (Juicy Fruit Part Ll) 3:25 Juicy Fruit Mtume After All 4:19 Al Jarreau After The Love Is Gone 3:58 The Best Of Earth, Wind & Fire Vol.II Earth Wind & Fire After the Morning After 5:33 Maze ft Frankie Beverly Again 5:02 Once Again John Legend Agony Of Defeet 4:28 The Best Of Parliament: Give Up The ... Parliament Ai No Corrida 6:26 The Dude Quincy Jones Ain't Gon' Beg You 4:14 Free Yourself Fantasia Ain't No Mountain High Enough 3:30 25 #1 Hits From 25 Years, Vol. I Diana Ross Ain't No Stopping Us Now 7:03 Boogie Nights Soundtrack McFadden & Whitehead Ain't No Sunshine 2:07 Lean On Me: The Best Of Bill Withers Bill Withers Ain't No Sunshine 3:44 Greatest Hits Dangelo Ain't No Sunshine 11:04 Wattstax - The Living Word (disc 2 of 2) Isaac Hayes Ain't Nobody 4:48 Night Clubbing Rufus and Chaka Kahn Ain't too proud to beg 2:32 The Temptations Ain't We Funkin' Now 5:36 Classics, Vol. -

The Sunclub Wetsuit Mp3, Flac, Wma

The Sunclub Wetsuit mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Wetsuit Country: Netherlands Released: 1999 Style: Trance, Euro House MP3 version RAR size: 1588 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1947 mb WMA version RAR size: 1488 mb Rating: 4.8 Votes: 378 Other Formats: DTS FLAC MOD WMA TTA AIFF DXD Tracklist Hide Credits Wetsuit (Jaydee Vs The H-Man Edit) 1 3:12 Edited By – Jaydee, The H-ManRemix – 3 Drives On A Vinyl* Wetsuit (Jaydee's Slight Diversion) 2 3:23 Mixed By – Atbe, Jaydee, TyparRemix – Jaydee Companies, etc. Published By – Next Mission Published By – Nanada Music Published By – Impression First Published By – TBM Publishing Phonographic Copyright (p) – Sony Music Entertainment (Holland) B.V. Copyright (c) – Sony Music Entertainment (Holland) B.V. Distributed By – Sony Music Credits Artwork [Animated & Visualized] – Desmond Vandenberg Design [Character Exclusively Designed For Dance Pool] – Dennis Van De Sande Design [Cover Design] – Chantal Creemers Producer, Mixed By, Written-By, Arranged By – Atbe, Jaydee, Typar Notes Animated & Visualized @ C3Pmania Published by Next Mission / Nanada, Impression First / TBM. ℗ 1999 Sony Music Entertainment (Holland) B.V. © 1999 Sony Music Entertainment (Holland) B.V. Distribution: Sony music Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Text): 5 099766 680415 Barcode (String): 5099766680415 Label Code: LC 06772 Rights Society: BIEM STEMRA Other (Distribution Code): CB 602 Other versions Title Category Artist Label Category Country Year (Format) DAN 666804 6, Dance Pool, DAN 666804 -

Derwood Love N Revenge

interested in working on a whole album with him. “He agreed so I took a break from the studio and headed back to my home town to do some more writing and a few months later I had another five song ideas so I was back in the studio for two more weeks,” he tells me. They now had six solid songs and he needed a break from the studio at this point to rest the musical part of his brain and he headed home again and began work on the last half of the album. It took Derwood another two Alchemy Studio’s Calgary who did all the drum and lead months to get some good ideas together then headed guitar work on the album by the way.” he explains to me. back to Calgary to finish recording the album. The guys DERWOOD The guys later had the style and sound that they both worked for another week and a half together and finally wanted for the album a sound template for the rest of finished the recordings. Derwood took another short the song ideas came pretty easily. He recycled a few of break of about a week or two then drove back to Calgary his older songs that he wrote when he was playing in to spend three solid days mastering with Jeff who also a grunge band and came up with a few new ideas. “I produced the album. would later return to Calgary for two more two week Looking forward to the future of this album and what long recording sessions and I finally had a professional the band will morph into, Derwood would like to be on studio album… and yes I’m very proud of it,” he smiles. -

Filmswelike Cg Cinéma Presents

A film by Mia Hansen-Løve filmswelike cg CinémA presenTs A film by miA HAnsen-løve WORLD PREMIERE AT TORONTO INTERNATIONAL FILM FESTIVAL - special presentation fRAnCe, 2014 french, english 131 minutes | Colour | DCP (D-Cinema) Produced by: Charles Gillibert (CG Cinéma) Press in Toronto & NYFF screenplay: mia Hansen-løve, sven Hansen-løve Ryan Werner Cinematographer: Denis lenoir [email protected] + 1 917 254 7653 editor: marion monnier Charlie Olsky Production Designer: Anna falguères [email protected] + 1 917 545 7260 sound: vincent vatoux, Damien Tronchot, Caroline Reynaud Production music: Daft Punk, Joe smooth, frankie Knuckles, CG Cinéma Terry Hunter, mK... Charles Gillibert Principal Cast: felix De Givry, Pauline etienne, vin- [email protected] cent macaigne, Greta Gerwig, Golshifteh farahani, laura smet, vincent lacoste Sales (international + Us) Kinology Aspect ratio: 2.39 Grégoire melin sound format: 5.1 [email protected] +33 6 87 51 03 96 Gaëlle mareschi [email protected] +33 6 63 03 28 97 Ram murali [email protected] +1 9172167471 tracklisting 1) Plastic Dreams (original version) - Jaydee 2) sueno latino (illusion first mixt) - sueno latino 3) follow me (club mix) - Aly Us 4) A Huge evergrowing Pulsating brain That Rules from The Centre Of The Ultraworld (Orbital Dance mix) - The Orb 5) The Whistle song (original version) - frankie Knuckles 6) Going Round (UbQ original mix) - Aaron smith feat D’bora 7) Caught in the middle (Gospel revival remix) - Juliet Roberts 8) Promised land (club mix) - Joe smooth -

A History of the Mt. Diablo Unitarian Universalist Church, 1951–1984

This book is dedicated to the memory of those who founded and nurtured this Fellowship and the church they created—those persistent seekers whose desire to search together gave us this building, whose search for truth shaped this questing religion, whose vision for themselves and their children created this sacred space that is our community, our shared church family. Our present is lit by their dreams and their deeds. [Adapted from the words of Emmy Lou Belcher] Scanned, transcribed and edited by Daniel B. Zwickel The text is set in Palatino Linotype, originally called Palatino when designed in 1948 by German graphic designer Hermann Zapf, then revised 1999 for Linotype and Microsoft. Named after 16th century Italian master of calligraphy Giambattista Palatino, the font is based on the humanist fonts of the Italian Renaissance, which mirror the letters formed by a broad nib pen; this gives it a calligraphic grace. (Wikipedia) Published by MDUUC Press, Mt. Diablo Unitarian Universalist Church 55 Eckley Lane, Walnut Creek, California 94596 (925) 934-3135 * [email protected] * www.mduuc.org Copyright © 1984 by Beverly Jeanne Scaff Copyright © 2015 by Mt. Diablo Unitarian Universalist Church All rights reserved Contents Chapter I The Fellowship Years, 1951–1960 1 Chapter II The Gilmartin Years Part 1 The Early Years, 1961–1967 49 Part 2 The Later Years, 1967–1974 101 Chapter III The Road to Eckley Lane 149 Chapter IV Years of Transition, 1975–1984 Part 1 Josiah Bartlett, Interim Minister, 1975 167 Part 2 Peter Christiansen, Minister, 1976–1982 -

Nummer Previous Position Titel Artiest Jaartal 1 11 Mary Go Wild

2015 nummer Previous Position titel artiest jaartal 1 11 Mary Go Wild Grooveyard 2 5 Don't you want me Felix 3 3 Energy Flash Joey Beltram 4 6 Insomnia Faithless 5 2 Plastic Dreams Jaydee 6 1 Age of love Age of love 7 8 Go Moby 8 10 Solid Session Format #1 9 4 Born Slippy Underworld 10 23 Love Stimulation (Paul van Dyk remix) Humate 11 103 Silence (DJ Tiësto mix) Delerium Ft. Sarah Mclachlan 12 9 Café del Mar Energy 52 13 12 The House Of God D.H.S. 14 7 Pull Over Speedy J 15 28 God Is A DJ Faithless 16 13 Dominator Human Resource 17 38 No Good (Start The Dance) Prodigy 18 14 James Brown is dead LA Style 19 24 Flight 643 Tiësto 20 87 Passion Gat Decor 21 15 Charly Prodigy 22 26 The First Rebirth Jones & Stephenson 23 17 Quadrophonia Quadrophonia 24 53 Mentasm Second Phase 25 70 Didn't I Give You Love Luvspunge 26 18 Loops And Things Jens 27 147 As The Rush Comes Motorcycle 28 64 Vallee De Larmes Rene & Gaston 29 51 Promised Land Joe Smooth 30 21 Android Prodigy 31 30 Greece 2000 Three Drives On A Vinyl 32 62 For An Angel Paul van Dyk 33 40 Better Off Alone Alice Deejay feat DJ Jurgen 34 48 Yaaah D-Shake 35 78 Zombie Nation Kernkraft 400 36 34 Firestarter Prodigy 37 98 Universal Nation Push 38 31 Out of Space Prodigy 39 72 Show Me Love Robin S 40 90 You Don't Know Me Armand Van Helden 41 125 Throw Paperclip People 42 19 Schöneberg Marmion 43 39 Get ready for this 2 Unlimited 44 120 Unfinished Sympathy Massive Attack 45 137 Sandstorm Darude 46 42 Burning Mk 47 68 The Nighttrain Kadoc 2015 nummer Previous Position titel artiest jaartal 48 45 Pump Up The Jam Technotronic 49 115 Der Klang der Familie 3 Phase feat Dr Motte 50 79 Time Problem Alice D in Wonderland 51 35 Give It Up Good Men, the 52 50 French Kiss Lil' Louis 53 206 Goodbye Thing 2 Men Will Move You 54 75 Children Robert Miles 55 47 Das Boot U96 56 27 Let's Groove (Morel's 4) Morels Groove 57 132 Seven Days & One Week B.B.E. -

Jaydee Plastic Dreams Mp3, Flac, Wma

Jaydee Plastic Dreams mp3, flac, wma DOWNLOAD LINKS (Clickable) Genre: Electronic Album: Plastic Dreams Country: France Released: 1996 Style: House MP3 version RAR size: 1308 mb FLAC version RAR size: 1361 mb WMA version RAR size: 1239 mb Rating: 4.4 Votes: 966 Other Formats: WAV ADX MP2 MP4 RA XM APE Tracklist A Plastic Dreams (Long Version) 10:35 B1 Plastic Dreams (Groove Mix) 6:00 B2 Plastic Dreams (Tribal Mix) 6:21 Credits Written-By, Producer, Mixed By – Robin "Jaydee" Albers* Notes Licensed from R & S Records All tracks written, produced & remixed by Robin "Jaydee" Albers Recorded & mixed at Binnenplaats - Vianen (Holland) by Jaydee Published in France by Scorpio Music (Black Scorpio) Sacem Distributed in France by Scorpoi Music (Polygram Distribution) Dedicated to every person who believes in me, my family, my doggie and my sincere friends (P) & (C) 1993 & 1996 R & S Records / Belgium. French re-press of this house-classic. Sleeve is exact copy of original R&S-sleeve back from 1993. Barcode and Other Identifiers Barcode (Scanned): 3 259119 213512 Matrix / Runout (Side A): 192135 -1 A Matrix / Runout (Side B): 192135 -1 B Other versions Category Artist Title (Format) Label Category Country Year RS 92027 Jaydee Plastic Dreams (12") R & S Records RS 92027 Belgium 1992 Plastic Dreams (CD, SPV 055-66613 Jaydee Total Recall SPV 055-66613 Germany 1993 Maxi) Plastic Dreams (12", JD 02 PROMO Jaydee R & S Records JD 02 PROMO Belgium 1997 Promo) Plastic Dreams (Hoxton Whore House none Jaydee Whores & HXTN Remix) none 2015 Recordings (File,