Semi-Annual Report #12

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stream Name Category Name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---TNT-SAT ---|EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU|

stream_name category_name Coronavirus (COVID-19) |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- TNT-SAT ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TF1 FULL HD 1 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 2 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 3 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 4 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE 5 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE O FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT M6 FHD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT PARIS PREMIERE FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TMC 1 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT 6TER FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CHERIE 25 FULL HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ARTE FR |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT RMC STORY SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT ---------- Information ---------- |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT TV5 MONDE FBS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT CNEWS HD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT France 24 |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO SD |EU| FRANCE TNTSAT FRANCE INFO HD -

Draft STRATEGY for TRANSITION to DIGITAL TERRESTRIAL

IMC-S/2015 Draft STRATEGY FOR TRANSITION TO DIGITAL TERRESTRIAL BROADCASTING IN THE REPUBLIC OF KOSOVA March 2015 Page 1 of 46 Komisioni i Pavarur i Mediave/Nezavisna Komisija za Medije/Independent Media Commission, Rr.Ul.Str. Perandori Justinian Nr. 14 Qyteza, Pejton, 10000 Prishtinë- Prištin- Pristina/Kosovë-Kosovo, Tel: (+381) (0) 38 245 031, Fax: (+381) (0) 38 245 034, E-mail: [email protected]; www.kpm-ks.org CONTENTS Introduction ................................................................................................................. 4 Definitions ................................................................................................................... 6 Drafting of the strategy ............................................................................................... 7 INDEPENDENT MEDIA COMMISSION ................................................................ 8 Broadcast Regulatory Authority in the Republic of Kosova ...................................... 8 MEDIA SECTOR IN KOSOVA ................................................................................ 8 Tv channels with terrestrial broadcast ........................................................................ 8 Radio channels with terrestrial broadcast ................................................................. 11 Distribution of program content to cable networks .................................................. 11 Program Service Providers........................................................................................ 11 Broadcasting -

00001. Rugby Pass Live 1 00002. Rugby Pass Live 2 00003

00001. RUGBY PASS LIVE 1 00002. RUGBY PASS LIVE 2 00003. RUGBY PASS LIVE 3 00004. RUGBY PASS LIVE 4 00005. RUGBY PASS LIVE 5 00006. RUGBY PASS LIVE 6 00007. RUGBY PASS LIVE 7 00008. RUGBY PASS LIVE 8 00009. RUGBY PASS LIVE 9 00010. RUGBY PASS LIVE 10 00011. NFL GAMEPASS 1 00012. NFL GAMEPASS 2 00013. NFL GAMEPASS 3 00014. NFL GAMEPASS 4 00015. NFL GAMEPASS 5 00016. NFL GAMEPASS 6 00017. NFL GAMEPASS 7 00018. NFL GAMEPASS 8 00019. NFL GAMEPASS 9 00020. NFL GAMEPASS 10 00021. NFL GAMEPASS 11 00022. NFL GAMEPASS 12 00023. NFL GAMEPASS 13 00024. NFL GAMEPASS 14 00025. NFL GAMEPASS 15 00026. NFL GAMEPASS 16 00027. 24 KITCHEN (PT) 00028. AFRO MUSIC (PT) 00029. AMC HD (PT) 00030. AXN HD (PT) 00031. AXN WHITE HD (PT) 00032. BBC ENTERTAINMENT (PT) 00033. BBC WORLD NEWS (PT) 00034. BLOOMBERG (PT) 00035. BTV 1 FHD (PT) 00036. BTV 1 HD (PT) 00037. CACA E PESCA (PT) 00038. CBS REALITY (PT) 00039. CINEMUNDO (PT) 00040. CM TV FHD (PT) 00041. DISCOVERY CHANNEL (PT) 00042. DISNEY JUNIOR (PT) 00043. E! ENTERTAINMENT(PT) 00044. EURONEWS (PT) 00045. EUROSPORT 1 (PT) 00046. EUROSPORT 2 (PT) 00047. FOX (PT) 00048. FOX COMEDY (PT) 00049. FOX CRIME (PT) 00050. FOX MOVIES (PT) 00051. GLOBO PORTUGAL (PT) 00052. GLOBO PREMIUM (PT) 00053. HISTORIA (PT) 00054. HOLLYWOOD (PT) 00055. MCM POP (PT) 00056. NATGEO WILD (PT) 00057. NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC HD (PT) 00058. NICKJR (PT) 00059. ODISSEIA (PT) 00060. PFC (PT) 00061. PORTO CANAL (PT) 00062. PT-TPAINTERNACIONAL (PT) 00063. RECORD NEWS (PT) 00064. -

International Premium Israel

INTERNATIONAL PREMIUM ISRAEL AFGHANISTAN ITALY AFRICA KOREA KURDISTAN ALBANIA MACEDONIA ARABIC MALAYSIA ARGENTINA MALTA AUSTRALIA NETHERLANDS AUSTRIA NEW ZEALAND BELGIUM NORWAY BRAZIL PAKISTAN BULGARIA PHILIPPINES CANADA POLAND CARRIBEAN PORTUGAL CHINA ROMANIA CZECH REPUBLIC RUSSIA SPAIN DENMARK SWEDEN FINLAND SWITZERLAND FRANCE THAILAND GERMANY TURKEY GREECE UNITED KINGDOM HUNGARY UNITED STATES INDONESIA VIETNAM AFGHANISTAN AFG: Arezo AFG: ARIANA INTERNATIONAL AFG: Aryana TV AFG: ATN AFGHAN AFG: ATN EUROPE AFG: ATN USA AFG: Jawan TV AFG: KHURSHID TV AFG: LEMAR AFG: NEGAAH AFG: PASHTO TV AFG: SHAMSHAD AFG: SROOD AFG: TAMADON TV AFG: Trace Naija HD AFG: RTA Afghanistan AF: IL TV AF: Mouridiyah tv (Senegal) AFRICA AF: EBC ETHIOPIA AF: Music TV Singhal AF: Vox Africa AF: AITInt'l AF: Ndiouroul TV (Senegal) AF: RTS 1 AFRICA AF: SOMALI CABLE AF: Neem TV Congo AF: ORTM AFRICA AF: Gabon TV AF: Nigezie TV (Nigeria) AF: AFRICA 24 AF: CRTV TV AF: NollyWood French AF: Africable AF: Equinoxe AF: Nollywood Movies AF: Africahwood TV AF: Maisha TV AF: Gtv Sports Plus (Ghana) AF: Erbu Africa AF: RTNC AF: Novelas TV AF: Africa Today TV AF: TVT International (Togo) AF: NTAi (Nigeria) AF: Africa TV AF: AIT International (Nigeria) AF: NTV (Uganda) AF: Africa TV 2 AF: Burkina Info (Burkina Faso) AF: Ole Tfm AF: Africa TV 3 AF: CANAL 225 (BENIN) AF: Oromia Sudan AF: ANN 7 South Africa AF: Channels 24 TV (Nigeria) AF: Qacaid TV AF: IBN TV Africa AF: ENN AF: RTN TV (Gabon) AF: Trace Africa AF: Espace TV (Guinee) AF: Rwanda tv AF: Rave TV (Nigeria) AF: Lamp Fall -

Bachelorarbeit, Medienlandschaft Im Kosovo Von Donika Cetaj

BACHELOR ARBEIT Frau Donika Cetaj Medienlandschaft im Kosovo 201 3 Fakultät: Medien BACHELORARBEIT Medienlandschaft im Kosovo Autorin: Frau Donika Cetaj Studiengang: Angewandte Medien Seminargruppe: AM10wM2-B Erstprüfer: Prof. Dr. Detlef Gwosc Zweitprüfer: StR. Marta da Ponte Einreichung: Hamburg, 23.07.2013 Faculty of Media BACHELOR THESIS Media environment in Kosovo author: Ms. Donika Cetaj course of studies: applied media seminar group: AM10wM2-B first examiner: Prof. Dr. Detlef Gwosc second examiner: StR. Marta da Ponte submission: Hamburg, 23.07.2013 Bibliografische Angaben Donika Cetaj Medienlandschaft im Kosovo Media environment in Kosovo 62 Seiten, 15.048 Wörter, Hochschule Mittweida, University of Applied Sciences, Fakultät Medien, Bachelorarbeit, 2013 Kurzreferat Die vorliegende Arbeit befasst sich mit der Medienlandschaft im Kosovo. Der jüngste Staat Europas ist immer noch im Konflikt mit Serbien. Dieser Konflikt und viele weitere geschichtliche Themen sind sehr wichtig für den Kosovo. Es gibt vieles, was man über dieses Land nicht weiß. Um den Aufbau und Strukturierung der Medienlandschaft und ihre Probleme zu verstehen muss man sein Wissen über den Kosovo erweitern. Diese Arbeit soll dieses Wissen vermitteln und eine Übersicht über die im Kosovo vorhandenen Medien geben. Der Kosovo hat sich im Jahre 2008 für unabhängig erklärt und somit von Serbien abgespalten. Dieser Konflikt ist im Jahre 2013 immer noch sehr aktuell. Der völkerrechtliche Status des Kosovo ist immer noch nicht fest abgeklärt. Die Medien im Land sind daher auch international gesehen eine wichtige Informationsquelle. Um so wichtiger ist es zu erfahren, wie diese Medien arbeiten und sich in diesem noch jungen Staat Kosovo in Zukunft entwickeln. Inhaltsverzeichnis V Inhaltsverzeichnis Inhaltsverzeichnis ..................................................................................................... -

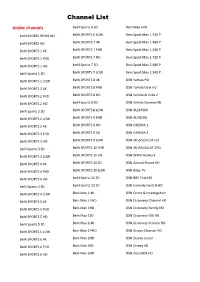

Channel List

Channel List Arabic channels beiN Sports 6 SD BeIn Max 4HD beIN SPORTS NEWS HD BeIN SPORTS 6 LOW Bein Sport Max 1 720 P beIN SPORTS HD BeIN SPORTS 7 4K Bein Sport Max 1 480 P BeIN SPORTS 1 4K BeIN SPORTS 7 FHD Bein Sport Max 1 240 P BeIN SPORTS 1 FHD BeIN SPORTS 7 HD Bein Sport Max 2 720 P BeIN SPORTS 1 HD beiN Sports 7 SD Bein Sport Max 2 480 P beiN Sports 1 SD BeIN SPORTS 7 LOW Bein Sport Max 2 240 P BeIN SPORTS 1 LOW BeIN SPORTS 8 4K OSN YaHala HD BeIN SPORTS 2 4K BeIN SPORTS 8 FHD OSN YaHala Oula HD BeIN SPORTS 2 FHD BeIN SPORTS 8 HD OSN YaHala Al Oula 2 BeIN SPORTS 2 HD beiN Sports 8 SD OSN YaHala Cinema HD beiN Sports 2 SD BeIN SPORTS 8 LOW OSN ALSAFWA BeIN SPORTS 2 LOW BeIN SPORTS 9 FHD OSN ALYOUM BeIN SPORTS 3 4K BeIN SPORTS 9 HD OSN CINEMA 1 BeIN SPORTS 3 FHD BeIN SPORTS 9 SD OSN CINEMA 2 BeIN SPORTS 3 HD BeIN SPORTS 9 LOW OSN MUSALSALAT HD beiN Sports 3 SD BeIN SPORTS 10 FHD OSN MUSALSALAT 2HD BeIN SPORTS 3 LOW BeIN SPORTS 10 HD OSN WWE Network BeIN SPORTS 4 4K BeIN SPORTS 10 SD OSN Animal Planet HD BeIN SPORTS 4 FHD BeIN SPORTS 10 LOW OSN Baby TV BeIN SPORTS 4 HD beiN Sports 11 SD OSN BBC First HD beiN Sports 4 SD beiN Sports 12 SD OSN Comedy Central HD BeIN SPORTS 4 LOW BeIn Max 1 4K OSN Crime & Investigation BeIN SPORTS 5 4K Bein Max 1 FHD OSN Discovery Channel HD BeIN SPORTS 5 FHD BeIn Max 1HD OSN Discovery Family HD BeIN SPORTS 5 HD BeIn Max 1SD OSN Discovery IDX HD beiN Sports 5 SD BeIn Max 2 4K OSN Discovery Science HD BeIN SPORTS 5 LOW Bein Max 2 FHD OSN Disney Channel HD BeIN SPORTS 6 4K BeIn Max 2HD OSN Disney Junior -

LEGAL VACUUM and LACK of TRANSPARENCY 2 23 Concentration

MEDIA OWNERSHIP AND FINANCES IN KOSOVO LEGAL VACUUM AND LACK OF TRANSPARENCY by ISUF BERISHA INTRODUCTION Media ownership and finances are two crucial aspects of media develop- ment in Kosovo that influence or even determine media freedom and inde- pendence. Various patterns of media ownership and financing have been used in Kosovo by the centres of political and financial power in order to influence the media and prevent them from serving the public interest and fulfilling their democratic role. This report is a result of research on media ownership and finances in Kosovo that was carried out from mid-July until mid-October 2015 within the South East European Media Observatory project. A lack of transparency in media ownership and in the forms of their financ- ing seems to be one of the main problems affecting the media field in Kosovo. It is a result of the existing legal vacuum concerning these issues. Limited avail- able data on media ownership and finances are mostly unreliable. To compen- sate for the scarcity and unreliability of information on these issues, a number of interviews with media representatives, media analysts and media market ex- perts were carried out during the process of data collection. However, media representatives were reluctant to answer questions about the issues addressed by this research. At best, they answered only parts of the questions. There were cases where they either avoided responding or clearly declined to respond. Owing to this climate of sensitivity and tension, some media analysts and me- dia market experts that we approached agreed to answer our questions only on condition of anonymity. -

Strategija Za Prelazak Na Digitalno Zemaljsko

KPM-S/2017 STRATEGIJA ZA PRELAZAK NA DIGITALNO ZEMALJSKO EMITOVANJE U REPUBLICI KOSOVO Komisioni i Pavarur i Mediave/Nezavisna Komisija za Medije/Independent Media Commission, Rr.Ul.Str. Perandori Justinian Nr. 124 Qyteza, Pejton, 10000 Prishtinë-Priština-Pristina/Kosovë-Kosovo, Tel: (+381) (0) 38 245 031, Fax: (+381) (0) 38 245 034, E-mail: [email protected];, www.kpm-ks.org; 1/47 Decembar 2017 Sadržaj Lista Definicija ..................................................................................................................................... 4 Lista skraćenica .................................................................................................................................... 6 Izvršni Rezime ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Metodologjia ......................................................................................................................................... 8 1. 1. UVOD .................................................................................................................................. 10 1. 1.1 Nezavisna Komisija za Medije .......................................................................................... 10 1.2 Pravni Okvir ................................................................................................................................. 11 2. Tehnički Okvir za zemaljsko televizijsko emitovanje ................................................................... -

Wars, Divisions, Integration (1990-2008)

TEACHING CONTEMPORARY SOUTHEAST EUROPEAN HISTORY SOURCE BOOKS FOR HISTORY TEACHERS VOLUME 2 WARS, DIVISIONS, INTEGRATION (1990-2008) 281011_WARS-DIVISIONS-INTEGRATION_I.indd 1 ѥ Publisher: Center for Democracy and Reconciliation in Southeast Europe (CDRSEE) English Language Editor: John White, Philip Carabott English Language Proofreader: Nerina Kioseoglou Page Layout: Ioanna Ghika Graphic Design: LYNX, Karavasiloglou Ioulia, Eressou 65, 10683, Athens, Greece Printing House: SAITI Publications S.A., Ermou 4, Metamorfosi 14452, Athens, Greece Print Run: 1,500 “This publication has been produced with the assistance of the European Union. The contents of this publication are the sole responsibility of the authors and can in no way be taken to reflect the views of the European Union.” CDRSEE Rapporteur to the Board for the Joint History Project: Costa Carras CDRSEE Executive Director: Zvezdana Kovac CDRSEE project team: Antonis Hadjiyannakis, Jenny Demetriou, Susan Nadeau, Ruth Sutton, Sasa Kulenovic, Michaela Zervidou and Elena Farini THE BOOK HAS BEEN PRODUCED ALSO WITH THE SUPPORT OF: Disclaimer: The designations employed and presentation of the material in the book do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the publisher (CDRSEE) nor on the sponsors. This book contains the views expressed by the authors in their individual capacity and may not necessarily reflect the views of the CDRSEE and the sponsoring agencies. The book is based on different contributions by our partners who provide content, warrant and represent that the content provided does not infringe any third party’s rights to the best of their knowledge. Therefore the publisher disclaims and is not liable for any relevant infringement of third party’s rights on content that has been contributed by the different partners. -

LEGAL VACUUM and LACK of TRANSPARENCY 2 23 Concentration

MEDIA OWNERSHIP AND FINANCES IN KOSOVO LEGAL VACUUM AND LACK OF TRANSPARENCY by ISUF BERISHA INTRODUCTION Media ownership and finances are two crucial aspects of media develop- ment in Kosovo that influence or even determine media freedom and inde- pendence. Various patterns of media ownership and financing have been used in Kosovo by the centres of political and financial power in order to influence the media and prevent them from serving the public interest and fulfilling their democratic role. This report is a result of research on media ownership and finances in Kosovo that was carried out from mid-July until mid-October 2015 within the South East European Media Observatory project. A lack of transparency in media ownership and in the forms of their financ- ing seems to be one of the main problems affecting the media field in Kosovo. It is a result of the existing legal vacuum concerning these issues. Limited avail- able data on media ownership and finances are mostly unreliable. To compen- sate for the scarcity and unreliability of information on these issues, a number of interviews with media representatives, media analysts and media market ex- perts were carried out during the process of data collection. However, media representatives were reluctant to answer questions about the issues addressed by this research. At best, they answered only parts of the questions. There were cases where they either avoided responding or clearly declined to respond. Owing to this climate of sensitivity and tension, some media analysts and me- dia market experts that we approached agreed to answer our questions only on condition of anonymity. -

Annual Report 2002

annual report 2002 IMPLEMENTATION OF ACTIVITIES AND USE OF FUNDS OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS human rights OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS ANNUAL REPORT 2002 The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights Palais des Nations - CH-1211 Geneva 10 - Switzerland Telephone: 41 22/917 90 00 - Fax: 41 22/917 90 04 Web site: www.unhchr.ch annual report 2002 OFFICE OF THE UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR HUMAN RIGHTS Prepared by the Resource Mobilization Unit of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Editorial Consultant: Marilyn Achiron Design and Desktop Publishing by Latitudesign, Geneva Printed by Atar SA, Geneva Photographs: UNICEF/HQ00-0682/Chalasani; UNICEF/HQ01-0375/Squire; UNICEF/HQ99-0916/LeMoyne; UNICEF/HQ00-0623/ LeMoyne; UNICEF/HQ98-0181/Hartley; UNICEF/HQ03-0030/Noorani; UNICEF/HQ99-0512/Horner; UNICEF/HQ99-0898/LeMoyne; UNICEF/HQ02-0083/Markisz. The designations employed and the presentation of the material in this report do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delimitation of its frontiers or boundaries. Table of contents Introduction by the High Commissioner . 5 Activities administered through UNOG The Annual Report 2002: A reader’s guide . 7 and UNOPS . 115 Funding of OHCHR. 9 Human rights support for peace-making, peacekeeping and peace-building activities Human rights trust funds established Introduction. 117 by the United Nations General Assembly Staff security . -

2S TV SN AIT International NG ANN 7 ZA Africable TV ML

African Countries (61 kanalen) — African Countries [AFR] ▬ 2S TV SN AIT International NG ANN 7 ZA Africable TV ML Africa 24 AFR Afrique Média CM BEN NG Channels TV NG CRTV CM Africa TV 3 SD Emmanuel TV NG Ebru TV KE GTV GH Joy News GH LC2 BJ Lamp Fall TV SN GoldMyne TV NG Nollywood Movies AFR ORTB TV BJ ORTM ML Olé TFM SN RTB TV BF RTG GN RTI 1 CI RTI 2 CI RTS1 SN Rave TV NG Sen TV SN TFM SN TFM Religions SN TPA AO Citizen TV KE Télé Tchad TD Tele Congo CG Voxafrica AFR Walf TV SN Wazobia TV NG Adom TV GH Kessben TV GH Blue Nile Channel SD Kalsan TV SO Horn Cable TV SO Jubaland TV SO SBC International SO Africa TV 4 SD Somali Cable SO Somaliland National TV SO Universal TV SO Africa TV 1 SD Africa TV 2 SD Somali National TV SO Africanews CG ESTV ET Telefishinka Caalamiga HD SO Telefishinka Caalamiga SO RTNC CG Biafra TV NG TVC News NG EBC ET KTN News KE Albania (225 kanalen) — Albania [AL] ▬ RTK 1 AL RTK1 (Backup) AL RTK 2 AL RTK 3 AL RTK 4 AL RTV 21 HD AL RTV 21 (Backup) AL RTV 21 Plus AL RTV 21 Popullore AL RTV 21 Popullore FHD AL RTV 21 Maqedonia AL RTV 21 Mix AL Klan HD AL Klan HD (Backup) AL KTV Kohavision AL KTV Kohavision HD AL Klan Kosova AL Klan Kosova HD AL Klan Plus HD AL Koha TV HD AL A1 Shqiptare AL Alsat M AL Alsat M (Backup) AL Top Channel HD AL Top Channel (Backup) AL T HD AL T AL RTSH 1 AL RTSH Toksor AL RTSH Sport AL TV Blue Sky Music AL Film Nje HD AL Film Dy HD AL Film Hits AL Film Aksion AL Film Komedi AL Film Autor AL Film Thriller AL Film Dramë AL Family HD AL Discovery HD AL Explorer Shkencë AL Explorer Shkencë