Scenes from the Life of Roz Chast Adam Gopnik, the New Yorker

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Addams Family Values: a Campy Cult Classic

Addams Family Values: A Campy Cult Classic By: Katie Baranauskas The Addams family is quite the odd bunch. Created by Charles Addams in a 1938 comic strip, the family has received countless renditions of their misadventures, including the 1993 sequel to The Addams Family: Addams Family Values. This is a rare instance in which the sequel is better than the original. The cast is by far one of the best, including greats like Anjelica Huston as Morticia, Christina Ricci as Wednesday, and Christopher Lloyd as Fester, as well as so many others. Every actor plays to their strengths, as well as their character's strengths, to craft a wonderful mix of comedy and drama. Some characters such as Fester and Gomez Addams have extreme slapstick comedy, whereas other characters such as Wednesday and Morticia Addams have a dry humor that also makes the audience chuckle: no laugh track needed. Along with all these fantastic characters comes an equally fantastic villain in Debbie Jelinsky, played by Joan Cusack. Debbie is immediately explored as a two-faced black widow, who will do anything to get the wealth and opulence she desires. Joan Cusack did the absolute most in this performance, and she looked fabulous as well. All of this is topped with an amazing script, which produced hundreds of lines I use to this day. A whole other article could be written on the iconic quotes from this movie, but my all-time favorite has to be when Morticia tells Debbie in the most monotone voice, "All that I could forgive, but Debbie… pastels?" This movie has just the right balance of creepiness and camp, reminding me of a Disney story set in a Tim Burton-esque world, where being "weird" is the new normal and everything is tinged with a gothic filter. -

Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960S and Early 1970S

TV/Series 12 | 2017 Littérature et séries télévisées/Literature and TV series Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy Electronic version URL: http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 DOI: 10.4000/tvseries.2200 ISSN: 2266-0909 Publisher GRIC - Groupe de recherche Identités et Cultures Electronic reference Dennis Tredy, « Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s », TV/Series [Online], 12 | 2017, Online since 20 September 2017, connection on 01 May 2019. URL : http://journals.openedition.org/tvseries/2200 ; DOI : 10.4000/tvseries.2200 This text was automatically generated on 1 May 2019. TV/Series est mis à disposition selon les termes de la licence Creative Commons Attribution - Pas d'Utilisation Commerciale - Pas de Modification 4.0 International. Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series o... 1 Light Shadows: Loose Adaptations of Gothic Literature in American TV Series of the 1960s and early 1970s Dennis Tredy 1 In the late 1960’s and early 1970’s, in a somewhat failed attempt to wrestle some high ratings away from the network leader CBS, ABC would produce a spate of supernatural sitcoms, soap operas and investigative dramas, adapting and borrowing heavily from major works of Gothic literature of the nineteenth and early twentieth century. The trend began in 1964, when ABC produced the sitcom The Addams Family (1964-66), based on works of cartoonist Charles Addams, and CBS countered with its own The Munsters (CBS, 1964-66) –both satirical inversions of the American ideal sitcom family in which various monsters and freaks from Gothic literature and classic horror films form a family of misfits that somehow thrive in middle-class, suburban America. -

The Addams Family

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Urbandale High School Theatre Arts Presents: The Addams Family The Addams Family: the musical takes you inside the funny, kooky, upside-down world of the Addams Family! There, to be sad is to be happy, to feel pain is to feel joy, and suffering is the stuff of dreams. Nonetheless, this quirky family still has to deal with many of the same challenges faced by any other family: the Addams kids are growing up! The Addamses have lived by their unique values for hundreds of years and Gomez and Morticia, the patriarch and matriarch of the clan, would be only too happy to continue living that way. Their beloved daughter Wednesday, however, is now an eighteen year-old young woman who is ready for a life of her own. She has fallen in love with Lucas Beineke, a sweet, smart boy from a normal, respectable Ohio family — the most un-Addams Family sounding person out there! And to make matters worse, she has invited the Beinekes to their home for dinner. In one fateful, hilarious night, secrets are disclosed, relationships are tested, and the Addams family must face up to the one horrible thing they’ve managed to avoid for generations: change. This musical comedy is fun for all ages so bring the whole family for a night of laughs, entertainment, and a heartwarming story about loving those around us. Performance Dates: Scan to Order Tickets! th th April 26 and 27 at 7:00 p.m. t h t h April 27 and 28 at 2:00 p.m. -

Why 1,000 Books Before Kindergarten?

Why 1,000 Books Before Kindergarten? Our hope with this program is to promote reading to newborns, infants, and toddlers; to encourage families to spend quality time together; and to promote pre-literacy and learning so children enter school ready to read, listen and learn. Research shows that reading books and sharing stories with your child is one of the best ways to help them enter school with the language skills they need to be ready to learn and grow. We’ve attached reading logs for your first 100 books to get you started. Simply color/check-off/cross-out the books as you read to your child. You can include stories that your child hears at library storytimes, in preschool and daycare– any and all books and stories count! A list on the back offers some fun suggestions of books to read with your child, but you don’t need to limit yourself to our list! Children often enjoy repeat visits with the same book or story, so feel free to include each additional reading as a book. When you’ve logged 50 titles, bring the completed log back into the library, pick up your prize and get the next Reading Log. When you have reached 1000 books, your child will receive a certificate and can add their name to our 1000 Books Before Kindergarten display. 1000 Books Seems Like a Lot of Books! Although 1,000 books sounds like a huge number, consider this: Read 4 books a week, and your child will have listened to 1,000 stories in five years. -

Wednesday Addams Is a Fictional Character Created by American Cartoonist Charles Addams in His Comic Strip the Addams Family

Wednesday Addams is a fictional character created by American cartoonist Charles Addams in his comic strip The Addams Family. In Addams' cartoons, which first appeared in The New Yorker, Wednesday and other members of the family had no names. When the characters were adapted to the 1964 television series, Charles Addams gave her the name "Wednesday", based on the well-known nursery rhyme line, "Wednesday's child is full of woe." The idea for the name was supplied by the actress and poet Joan Blake, an acquaintance of Addams. She is the sister of Pugsley Addams, and she is the only daughter of Gomez and Morticia Addams. Wednesday's most notable features are her pale skin and long, dark twin braids. She seldom shows emotion and is generally bitter. Wednesday usually wears a black dress with a white collar, black stockings and black shoes. In the 1960s series, she is significantly more sweet-natured, although her favorite hobby is raising spiders; she is also a ballerina. Wednesday's favorite toy is her Marie Antoinette doll, which her brother guillotines (at her request). She is stated to be six years old in the television series' pilot episode. In one episode, she is shown to have several other headless dolls as well. She also paints pictures (including a picture of trees with human heads) and writes a poem dedicated to her favorite pet spider, Homer. Wednesday is deceptively strong; she is able to bring her father down with a judo hold. Wednesday has a close kinship with the family's giant butler Lurch. -

Pros-A180.Pdf

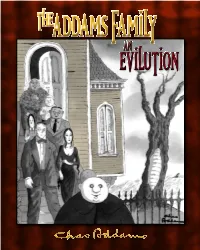

TheAddAms FAmily an Evilution 1 tthehe FamilyFamily Gomez and Pugsley are enthusiastic. Morticia is even in disposition, muted, witty, sometimes deadly. Grandma Frump is foolishly good-natured. Wednesday is her mother’s daughter. A closely knit family, the real head being Morticia—although each of the others is a definite character—except for Grandma, who is easily led. Many of the troubles they have as a family are due to Grandma’s fumbling, weak character. The house is a wreck, of course, but this is a house-proud family just the same and every trap door is in good repair. Money is no problem. Strong family values are evident throughout Charles Addams’s depictions of the family from the dark side. They hang together; they feel secure with one another; they have rules and morals that keep the family unit intact. Sure, the logs they burn in their fireplace are carved to look like men; they moonbathe instead of sunbathe; they prefer gazing at the sweeping vista of a cemetery rather than sunlit rolling hills; they take their outings in Central Park in the dead of night. The point is, they do these things together. They might be scary, weird, creepy, and macabre, but The Addams Family is our secret envy. If only our family dinners could be so much fun! 2 3 “Well, he certainly doesn’t take after my side of the family.” 4 5 “it’s the children, darling, back from camp.” 6 “you forgot the eye of newt.” 7 the “evilution” of Charles Addams’s singularly eccentric family began long before the television and film interpretations made them icons of American popular culture. -

CAP UCLA Presents Roz Chast and Her Memoir at Royce Hall Sun, Jan 31

Press Release Friday, December 11th, 2015 Contact: Ashley Eckenweiler [email protected] CAP UCLA Presents Roz Chast and her memoir at Royce Hall Sun, Jan 31 Center for the Art of Performance at UCLA is proud to present Roz Chast, reading from her memoir Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? Tickets ($19-$49) for Sunday, January 31 at 4 p.m. are available now at cap.ucla.edu, via Ticketmaster and at the UCLA Central Ticket Office at 310.825.2101. Since joining The New Yorker in 1978, Roz Chast has established herself as one of our greatest artistic chroniclers of the anxieties, superstitions, furies, insecurities, and surreal imaginings of modern life. Her works are typically populated by hapless but relatively cheerful “everyfolk,” and she addresses the universal topics of guilt, aging, families, money, real estate, and, as she would say, “much, much more!” More than 1,000 of her cartoons have been printed in The New Yorker since 1978. In this performance, she will read from her first memoir which harnesses her signature wit as she recounts her experience caring for her aging parents. Spanning the last several years of their lives and told through four-color cartoons, family photos and documents, and a narrative as rife with laughs as it is with tears, Chast’s memoir is both comfort and comic relief for anyone experiencing the life- altering loss of elderly parents. The evening will showcase the full range of Chast’s talent as cartoonist and storyteller. Following the reading, there will be a Q&A with Chast. -

Norman Rockwell Museum Featured Illustrators, 1993–2008

Norman Rockwell Museum Featured Illustrators, 1993–2008 Contemporary Artists Jessica Abel John Burgoyne Leon Alaric Shafer Elizabeth Buttler Fahimeh Amiri Chris Calle Robert Alexander Anderson Paul Calle Roy Anderson Eric Carle Margot Apple Alice Carter Marshall Arisman Roz Chast Natalie Asencios Jean Claverie Istvan Banyai Sue Coe James Barkley Raúl Colon Mary Brigid Barrett Ken Condon Gary Baseman Laurie Cormier Leonard Baskin Christin Couture Melinda Beck Kinuko Y. Craft Harry Beckhoff R. Crumb Nnekka Bennett Howard Cruse Jan and Stan Berenstain (deceased) Robert M. Cunningham Michael Berenstain Jerry Dadds John Berkey (deceased) Ken Dallison Jean-Louis Besson Paul Davis Diane Bigda John Dawson Guy Billout Michael Deas Cathie Bleck Etienne Delessert R.O. Blechman Jacques de Loustal Harry Bliss Vincent DiFate Barry Blitt Cora Lynn Deibler Keith Birdsong Diane and Leo Dillon Thomas Blackshear Steve Ditko Higgins Bond Libby Dorsett Thiel William H. Bond Eric Drooker Juliette Borda Walter DuBois Richards Braldt Bralds Michael Dudash Robin Brickman Elaine Duillo Steve Brodner Jane Dyer Steve Buchanan Will Eisner Yvonne Buchanan Dean Ellis Mark English Richard Leech Teresa Fasolino George Lemoine Monique Felix Gary Lippincott Ian Falconer Dennis Lyall Brian Fies Fred Lynch Theodore Fijal David Macaulay Floc’h Matt Madden Bart Forbes Gloria Malcolm Arnold Bernie Fuchs Mariscal Nicholas Gaetano Bob Marstall John Gilmore Marvin Mattelson Julio Granda Lorenzo Mattotti Robert Guisti Sally Mavor Carter Goodrich Bruce McCall Mary GrandPré Robert T. McCall Jim Griffiths Wilson McClean Milt Gross Richard McGuire James Gurney Robert McGinnis Charles Harper James McMullan Marc Hempel Kim Mellema Niko Henrichon David Meltzer Mark Hess Ever Meulen Al Hirschfeld (deceased) Ron Miller John Howe Dean Mitchell Roberto Innocenti Daniel Moore Susan Jeffers Françoise Mouly Frances Jetter Gregory Manchess Stephen T. -

LYNDA BARRY Associate Professor in Interdisciplinary Creativity Chazen Family Distinguished Chair in Art [email protected]

LYNDA BARRY Associate Professor in Interdisciplinary Creativity Chazen Family Distinguished Chair in Art [email protected] EDUCATION 1978 BA The Evergreen State College, Olympia WA RECENT HONORS AND AWARDS: 2020 MacArthur Fellow 2020 Nomination for Cartoonist of the Year – National Cartoonists Society Rubin Award 2019 United States Artist Award 2019 Nomination for Cartoonist of the Year –National Cartoonists Society Ruben Award 2018 Nomination for Cartoonist of the Year –National Cartoonists Society Ruben Award 2017 Milton Caniff Lifetime Achievement Award – National Cartoonists Society 2016 Inducted into the Cartoonist’s Hall of Fame – Ruben awards ComiCon San Diego 2016- Chazen Family Endowment Distinguished Artist Chair 2015 -Doctor of Arts, Honorary Degree, Philadelphia University of Art 2014- Holtz Center Outreach Fellowship -Edna Wiechers Art in Wisconsin Award, Arts Institute -Society of Illustrators 2014 Push and Kicks Award of Excellence in the World of Graphic Books -French Edition of “One Hundred Demons”, official selection of the Angouleme Festival, Agoulême, France -“Freddie Stories” nominated for Ignatz Awards, outstanding Anthology Selected Awards - Two additional William Eisner awards, - The American Library Association’s Alex Award, - The Wisconsin Library Association’s RR Donnelly Award, - Washington State Governor’s Award - Wisconsin Visual Art Lifetime Achievement Award BOOKS 2019 Making Comics (Drawn and Quarterly) 2017 The Good Times are Killing me, revised new hardcover edition with paintings and new afterword -

Roz Chast: Cartoon Memoirs, Celebrating Almost Four Decades of Outstanding Artistic Accomplishment

ROZROZ CHAST: CHAST: CARTOON CARTOON MEMOIRS MEMOIRS . DISTINGUISHED . ILLUSTRATOR . S ERIES . Like many readers of The New Yorker and other popular publications, I have always been drawn to Roz Chast’s singular wit, and look forward to each new cartoon recounting the exploits of characters whom I feel I have come to know. Inspired, as Norman Rockwell was, by life’s small moments, her intelligent, expressive drawings prove that fact can be stranger than fiction, and that one need not go far to find comic relief in our crazy, irrepressible world. Norman Rockwell Museum is honored to present the art of this distinguished illustration master in Roz Chast: Cartoon Memoirs, celebrating almost four decades of outstanding artistic accomplishment. The exhibition offers the first presentation of original works from her acclaimed visual memoir, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, which chronicles the lives of her aging parents with heartfelt humor and emotion. The full range of the Chast’s talents and the breadth of her career are also revealed in her legendary cartoons for The New Yorker; book illustrations for Around the Clock, What I Hate from A to Z, Marco Goes to School, and 101 Two-Letter Words, among others; intricately-painted Ukrainian character eggs; and one-of-a-kind hand-made storytelling rugs. The Distinguished Illustrator Exhibition Series honoring the unique contributions of exceptional visual communicators is presented by the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies, the nation’s first research institute devoted to the art of illustration. The Distinguished Illustrator series reflects the impact and evolution of published art, and of Norman Rockwell’s beloved profession, which remains vibrant and ever-changing. -

Charles Addams the Addams Family: an Evilution H

POMEGRANATE COMMUNICATIONS, INC. Box 808022 • Petaluma, CA 94975‐8022 Tel: 800 ‐227‐1428 • Fax: 800‐848‐4372 • www.pomegranate.com • [email protected] Visit us on Facebook: http://www.facebook.com/pomcom COMING FROM POMEGRANATE IN MARCH 2010 Charles Addams The Addams Family: An Evilution H. Kevin Miserocchi The “evilution” of Charles Addams’s singularly eccentric family began long before the television and film interpretations made them icons of American popular culture. Addams first created Morticia, Lurch, and The Thing in a cartoon published in a 1938 issue of the New Yorker—though he hadn’t named them at the time, or even conceived of a family unit. (When he did name the deadly matriarch, he was inspired by the Yellow Pages listing for “Morticians.”) Other characters were born and developed in a multitude of Addams’s cartoons over the next twenty-six years, before the cheerfully creepy clan debuted on ABC television in 1964 and later on the big screen, twice, in 1991 and 1993. The Addams Family: An Evilution is the first book to trace The Addams Family history in one definitive volume, presenting more than 200 cartoons created by Charles “Chas” Addams (American, 1912–1988) throughout his prolific career, including at least 50 cartoons that have never been published before. Text by H. Kevin Miserocchi, director of the Tee and Charles Addams Foundation, offers a revealing chronology of each character’s evolution (for instance, did you know that Addams originally named Pugsley “Pubert”?), while Addams’s own incisive character descriptions, originally penned for the benefit of the television show producers, introduce each chapter. -

The Addams Family Is Inspired by the Creations of the Legendary American Cartoonist Charles Addams, Who Lived from 1912 Until 1988

The Man Behind the Family The musical The Addams Family is inspired by the creations of the legendary American cartoonist Charles Addams, who lived from 1912 until 1988. In 1933, when he was just 21, his work was published in The New Yorker, and over the course of nearly six decades, he became one of the magazine’s most cherished contributors. Bizarre, macabre and weird are all words that have been used to describe Charles Addams’ cartoons. Yet adjectives such as charming, enchanting and Photo: Lane Stewart tender can just as accurately be employed to depict the same body of work, as well as the man himself. His unique style and wonderfully crafted cartoons enabled his work to transcend such dichotomies for his millions of fans worldwide. Charles Addams is most widely known for his characters that came to be called The Addams Family, a group that evolved into multiple television shows, motion pictures and now this Broadway musical. Gomez, Morticia, Uncle Fester, Wednesday, Pugsley, Grandma and Lurch existed in various forms and aspects of Addams’ cartoons dating back to the 1930s but were not actually named by him until the early 1960s, when the television series was created. Surprisingly, The Addams Family characters appear in only a small number of the artist’s several thousand works. The majority of his cartoons are occupied by hundreds of other characters, but there is little doubt that those that come to life on this stage are his most “Are you unhappy, darling?” “Oh yes, yes! Completely.” beloved creations. Over 15 books of his drawings have been published around the world, including the new collection, The Addams Family: An Evilution, the first complete history of The Addams Family, including more than 200 cartoons, many never previously published.