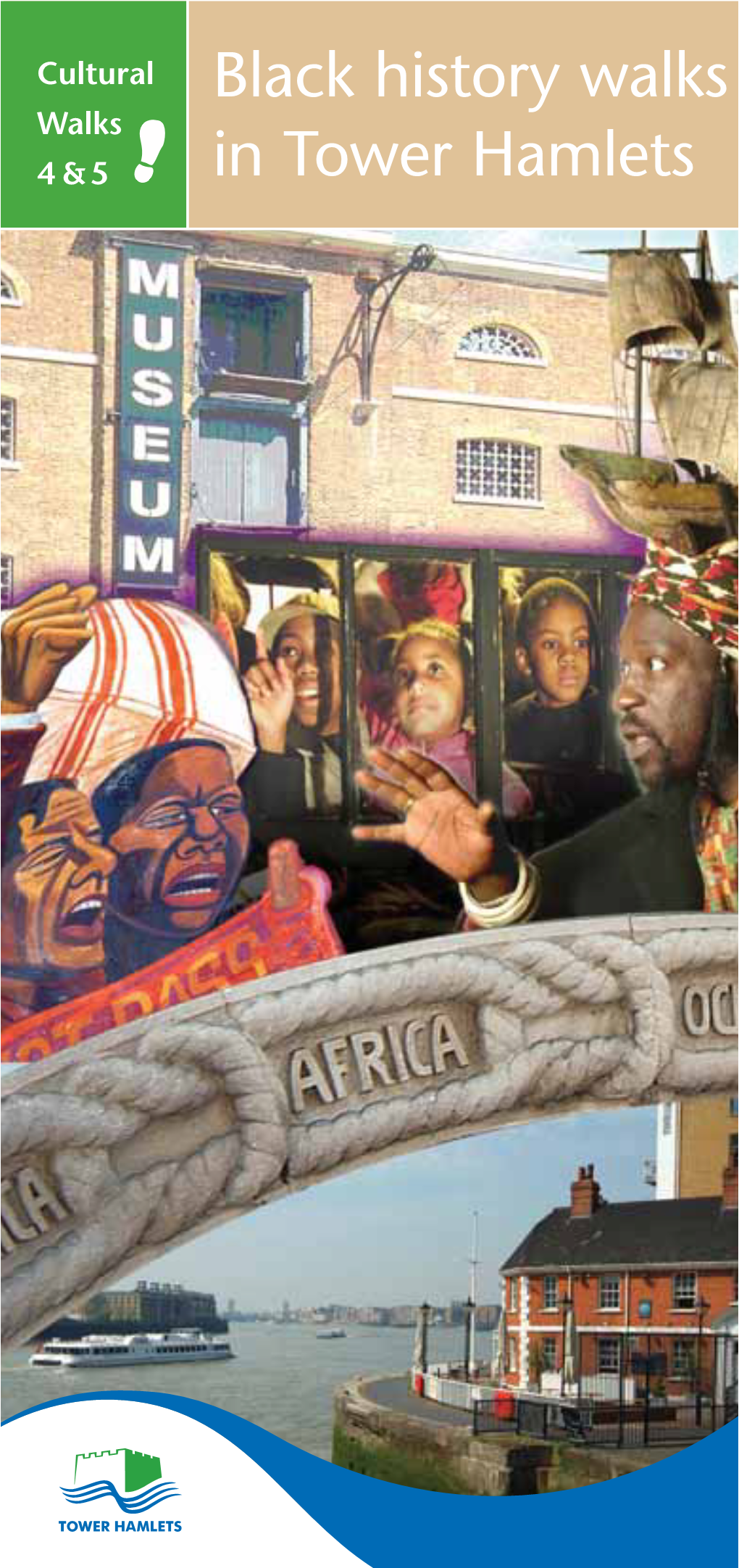

Black History Walks in Tower Hamlets

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Residential Update

Residential update UK Residential Research | January 2018 South East London has benefitted from a significant facelift in recent years. A number of regeneration projects, including the redevelopment of ex-council estates, has not only transformed the local area, but has attracted in other developers. More affordable pricing compared with many other locations in London has also played its part. The prospects for South East London are bright, with plenty of residential developments raising the bar even further whilst also providing a more diverse choice for residents. Regeneration catalyst Pricing attraction Facelift boosts outlook South East London is a hive of residential Pricing has been critical in the residential The outlook for South East London is development activity. Almost 5,000 revolution in South East London. also bright. new private residential units are under Indeed pricing is so competitive relative While several of the major regeneration construction. There are also over 29,000 to many other parts of the capital, projects are completed or nearly private units in the planning pipeline or especially compared with north of the river, completed there are still others to come. unbuilt in existing developments, making it has meant that the residential product For example, Convoys Wharf has the it one of London’s most active residential developed has appealed to both residents potential to deliver around 3,500 homes development regions. within the area as well as people from and British Land plan to develop a similar Large regeneration projects are playing further afield. number at Canada Water. a key role in the delivery of much needed The competitively-priced Lewisham is But given the facelift that has already housing but are also vital in the uprating a prime example of where people have taken place and the enhanced perception and gentrification of many parts of moved within South East London to a more of South East London as a desirable and South East London. -

Crawford Building, 112 Whitechapel High Street, Aldgate, London, London

Crawford Building, 112 Whitechapel High Street, Aldgate, London, London. E1 7AP 980,000 • 2 bedrooms • 2 bathrooms • Built-In Wardrobes • Large Balcony • Central Heating • Comfy Cooling • At Aldgate Tube Station • Close to all trendy amenities in The Square Mile Ref: PRA10137 Viewing Instructions: Strictly By Appointment Only General Description A luxury two bedroom, two bathroom apartment situated in The Crawford Building development, part of the Aldgate regeneration. This 977 Square Foot apartment is exquisitely decorated and features high specification throughout offering a fully fitted contemporary open plan kitchen, reception, floor to ceiling windows, fitted large 'his and hers' wardrobes in the master bedroom, a second large double bedroom, a long private balcony with access from both the reception and master bedroom and storage. The Crawford Building benefits from 24 hour concierge and is ideally built above Aldgate East tube station and is situated in the City of London, a superb location, in close proximity to a range of shops, bars and restaurants as well as to the trendy Brick Lane, Shoreditch and Tower Hill areas. Accommodation Services EPC Rating:87 Tenure We are informed that the tenure is Not Specified Council Tax Band Not Specified All measurements are approximate. The deeds have not been inspected. Please note that we have not tested the services of any of the equipment or appliances in this property. Stamp duty is not payable up to £125,000. From £125,001 to £250,000 - 2% of Purchase Price. From £250,001 to £925,000 - 5% of Purchase Price. From £925,001 to £1,500,000 - 10% of Purchase Price. -

JL AAAA Reviews

A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE BOOK FOR VISITORS AND LONDONERS Rachel Kolsky and Roslyn Rawson Reviews UK Press US Press Israel Press Amazon.co.uk / Amazon.com Hebrew Other / Readers Comments CONTACT RACHEL KOLSKY [email protected] / www.golondontours.com for more information, signed copies and book events A COMPREHENSIVE GUIDE BOOK FOR VISITORS AND LONDONERS Rachel Kolsky and Roslyn Rawson Reviews UK Press Jewish London - Reviews - [email protected] - www.golondontours.com 9 THE ARCHER - www.the-archer.co.uk MARCH 2012 KALASHNIKOV KULTUR Ultimate guide to Jewish London By Ricky Savage, the voice of social irresponsibility Two authors have compiled the ultimate guide to Jewish London and will introduce it in person at a special event at the Phoenix Cinema this month. Rachel Kolsky, an Lizzie Land East Finchley resident since 1995 and a trustee of the Phoenix since 1997, co-authored Yes, it’s here, and the world of theme parks will never be Jewish London with Roslyn Rawson. the same. Why? Because the French have decided that what The 224-page guide covers holidaymakers need is a whole new experience based on where to stay, eat, shop and pray, with detailed maps, practical the life, loves and battles of a small Corsican. Welcome to advice, travel information and Napoleon Land! more than 200 colour photo- There in a eld just outside Paris you will be able to celebrate the man graphs. who conquered Europe and then lost it again, marvel at the victories, Special features include attend the glorious coronation and sign up to join the Old Guard. -

Shaken, Not Stunned

Shaken, not stunned: The London Bombings of July 2005 1 Work in progress – not for circulation or citation! Project leader: Dr. Eric K Stern Case researchers: Fredrik Fors Lindy M Newlove Edward Deverell 1 This research has been made possible by the support of the Swedish National Defence College, the Swedish Emergency Management Agency and the Critical Incident Analysis Group. 1 Executive summary - The bombings of July 2005 On July 7 th , the morning rush hours in London formed the backdrop for the first suicide bombings in Western Europe in modern times. Three different parts of the London subway system were attacked around 08.50: Aldgate, Edgware Road, and Russell Square. 2 The three Tube trains were all hit within 50 seconds time. A bomb on the upper floor of a double-decker bus at Tavistock Square was detonated at 09.47. In the terrorist attacks, four suicide bombers detonated one charge each, killing 52 people. Seven people were killed by the blasts at Aldgate, six at Edgware Road, 13 at Tavistock Square, and 26 at Russel Square – in addition to the suicide bombers themselves. More than 700 people were injured. Hundreds of rescue workers were engaged in coping with the aftermath. Over 200 staff from the London Fire Brigade, 450 staff and 186 vehicles from the London Ambulance Service, several hundred police officers from the Metropolitan Police and from the City of London Police, as well as over 130 staff from the British Transport Police were involved. Patients were sent to 7 area hospitals. 3 Crucial Decision Problems 1. -

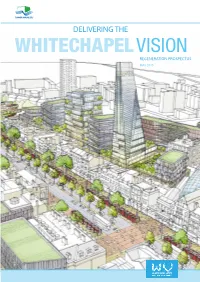

Whitechapel Vision

DELIVERING THE REGENERATION PROSPECTUS MAY 2015 2 delivering the WHitechapel vision n 2014 the Council launched the national award-winning Whitechapel Masterplan, to create a new and ambitious vision for Whitechapel which would Ienable the area, and the borough as a whole, to capitalise on regeneration opportunities over the next 15 years. These include the civic redevelopment of the Old Royal London Hospital, the opening of the new Crossrail station in 2018, delivery of new homes, and the emerging new Life Science campus at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL). These opportunities will build on the already thriving and diverse local community and local commercial centre focused on the market and small businesses, as well as the existing high quality services in the area, including the award winning Idea Store, the Whitechapel Art Gallery, and the East London Mosque. The creation and delivery of the Whitechapel Vision Masterplan has galvanised a huge amount of support and excitement from a diverse range of stakeholders, including local residents and businesses, our strategic partners the Greater London Authority and Transport for London, and local public sector partners in Barts NHS Trust and QMUL as well as the wider private sector. There is already rapid development activity in the Whitechapel area, with a large number of key opportunity sites moving forward and investment in the area ever increasing. The key objectives of the regeneration of the area include: • Delivering over 3,500 new homes by 2025, including substantial numbers of local family and affordable homes; • Generating some 5,000 new jobs; • Transforming Whitechapel Road into a destination shopping area for London • Creating 7 new public squares and open spaces. -

London and Middlesex in the 1660S Introduction: the Early Modern

London and Middlesex in the 1660s Introduction: The early modern metropolis first comes into sharp visual focus in the middle of the seventeenth century, for a number of reasons. Most obviously this is the period when Wenceslas Hollar was depicting the capital and its inhabitants, with views of Covent Garden, the Royal Exchange, London women, his great panoramic view from Milbank to Greenwich, and his vignettes of palaces and country-houses in the environs. His oblique birds-eye map- view of Drury Lane and Covent Garden around 1660 offers an extraordinary level of detail of the streetscape and architectural texture of the area, from great mansions to modest cottages, while the map of the burnt city he issued shortly after the Fire of 1666 preserves a record of the medieval street-plan, dotted with churches and public buildings, as well as giving a glimpse of the unburned areas.1 Although the Fire destroyed most of the historic core of London, the need to rebuild the burnt city generated numerous surveys, plans, and written accounts of individual properties, and stimulated the production of a new and large-scale map of the city in 1676.2 Late-seventeenth-century maps of London included more of the spreading suburbs, east and west, while outer Middlesex was covered in rather less detail by county maps such as that of 1667, published by Richard Blome [Fig. 5]. In addition to the visual representations of mid-seventeenth-century London, a wider range of documentary sources for the city and its people becomes available to the historian. -

N277 Islington – Mile End – Crossharbour

N277 Islington – Mile End – Crossharbour N277 Sunday night/Monday morning Islington White Lion Street 0010 0035 0054 0118 0143 0210 0240 0310 0340 0410 0434 0504 0534 Islington Angel (Upper Street) 0011 0036 0055 0119 0144 0211 0241 0311 0341 0411 0435 0505 0535 Highbury Corner St Paul's Road 0018 0043 0102 0126 0151 0217 0247 0317 0347 0417 0441 0511 0541 Dalston Junction Dalston Lane 0025 0050 0109 0133 0158 0223 0253 0322 0352 0422 0446 0516 0546 Hackney Central Station Graham Rd. 0030 0055 0114 0138 0202 0227 0257 0326 0356 0426 0450 0520 0550 Lauriston Road Church Crescent 0037 0102 0121 0145 0209 0234 0304 0332 0402 0432 0455 0525 0555 Mile End Grove Road 0042 0107 0126 0150 0214 0239 0309 0337 0407 0436 0459 0529 0559 Limehouse Burdett Road 0047 0112 0131 0155 0218 0243 0313 0341 0411 0440 0503 0533 0603 Canary Wharf (DLR) Station 0052 0117 0136 0200 0223 0248 0318 0346 0415 0444 0507 0537 0607 Westferry Road Cuba Street 0054 0119 0138 0202 0225 0250 0320 0348 0418 0447 0511 0541 0611 Millwall Dock Bridge 0057 0122 0141 0204 0227 0252 0322 0350 0420 0450 0514 0544 0614 Westferry Road East Ferry Road 0100 0125 0144 0207 0230 0255 0325 0353 0423 0453 0517 0547 0617 Crossharbour Asda 0103 0128 0147 0210 0233 0258 0328 0356 0426 0456 0520 0550 0620 N277 Monday night/Tuesday morning to Thursday night/Friday morning Islington White Lion Street 0010 0035 0054 0118 0143 0210 0240 0310 0340 0410 0434 0504 0534 Islington Angel (Upper Street) 0011 0036 0055 0119 0144 0211 0241 0311 0341 0411 0435 0505 0535 Highbury Corner St Paul's Road 0018 0043 0102 0126 0151 0217 0247 0317 0347 0417 0441 0511 0541 Dalston Junction Dalston Lane 0025 0050 0109 0133 0158 0223 0253 0322 0352 0422 0446 0516 0546 Hackney Central Station Graham Rd. -

Denbury House Bow Road

Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com DENBURY HOUSE BOW ROAD OIEO £400,000 FOR SALE REF: 2534034 2 Bed, Apartment, Private Garden, Permit Parking South Facing Private Garden - Low Rise Development - Chain Free - Two Bedroom Apartment - Ex Local Authority - Located moments walk from Bromley by Bow Station Guide Price £395,000 to £410,000. Wonderful two double bedroom apartment boasting large south facing private garden, located in this well kept low rise ex local authority development walking distance to Bromley by Bow Tube Station and Devon's road DLR Stations with easy access to the City and Canary Wharf. The property consists large bright reception with access to the private garden, modern kitchen, separate WC and family bathroom, two good sized double bedrooms, one with fitted storage. Offer... continued below Train/Tube - Bromley-by-Bow, Bow Church, Mile End, Bow Road Local Authority/Council Tax - Tower Hamlets Tenure - Leasehold Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com DENBURY HOUSE BOW ROAD Reception Reception Alt 1 Reception Alt 2 Kitchen Master Bedroom Second Bedroom Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com DENBURY HOUSE BOW ROAD Second Bedroom Alt Bathroom Exterior Bow Sales, 634-636 Mile End Road, Bow, London E3 4PH T 020 8981 2670 E [email protected] W www.ludlowthompson.com DENBURY HOUSE BOW ROAD Please note that this floor plan is produced for illustration and identification purposes only. -

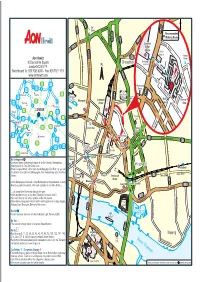

Aon Hewitt-10 Devonshire Square-London EC2M Col

A501 B101 Old C eet u Street Str r t A1202 A10 ld a O S i n Recommended h o A10 R r Walking Route e o d et G a tre i r d ld S e t A1209 M O a c Liverpool iddle t h sex Ea S H d Street A5201 st a tre e i o A501 g e rn R Station t h n S ee Police tr S Gr Station B e e t nal Strype u t Beth B134 Aon Hewitt C n Street i t h C y Bishopsgate e i l i t N 10 Devonshire Square l t Shoreditch R a e P y East Exit w R N L o iv t Shoreditcher g S St o Ra p s t London EC2M 4YP S oo re pe w d l o e y C S p t tr h S a tr o i A1202 e t g Switchboard Tel: 020 7086 8000 - Fax: 020 7621 1511 d i e h M y t s H i D i R d www.aonhewitt.com B134 ev h B d o on c s Main l a h e t i i r d e R Courtyard s J21 d ow e e x A10 r W Courtyard M11 S J23 B100 o Wormwood Devonshire Sq t Chis h e r M25 J25 we C c e l S J27 l Str Street a e M1 eet o l t Old m P Watford Barnet A12 Spitalfields m A10 M25 Barbican e B A10 Market w r r o c C i Main r Centre Liverpool c a r Harrow Pl A406 J28 Moorgate i m a k a e t o M40 J4 t ld S m Gates C Harrow hfie l H Gate Street rus L i u a B le t a H l J1 g S e J16 r o J1 Romford n t r o e r u S e n tr A40 LONDON o e d e M25 t s e Slough M t A13 S d t it r c A1211 e Toynbee h J15 A13 e M4 J1 t Hall Be J30 y v Heathrow Lond ar is on W M M P all e xe Staines A316 A205 A2 Dartford t t a London Wall a Aldgate S A r g k J1 J2 s East s J12 Kingston t p Gr S o St M3 esh h h J3 am d s Houndsditch ig Croydon Str a i l H eet o B e e A13 r x p t Commercial Road M25 M20 a ee C A13 B A P h r A3 c St a A23 n t y W m L S r n J10 C edldle a e B134 M20 Bank of e a h o J9 M26 J3 heap adn Aldgate a m sid re The Br n J5 e England Th M a n S t Gherkin A10 t S S A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 A21 r t e t r e e DLR Mansion S Cornhill Leadenhall S M e t treet t House h R By Underground in M c o Bank S r o a a Liverpool Street underground station is on the Central, Metropolitan, u t r n r d DLR h i e e s Whitechapel c Hammersmith & City and Circle Lines. -

861 Sq Ft Headquarters Office Building Your Own Front Door

861 SQ FT HEADQUARTERS OFFICE BUILDING YOUR OWN FRONT DOOR This quite unique property forms part of the building known as Rotherwick House. The Curve comprises a self-contained building, part of which is Grade II Listed, which has been comprehensively refurbished to provide bright contemporary Grade A office space. The property — located immediately to the east of St Katharine’s Dock and adjoining Thomas More Square — benefits from the immediate area which boasts a wide variety of retail and restaurant facilities. SPECIFICATION • Self-contained building • Generous floor to ceiling heights • New fashionable refurbishment • Full-height windows • New air conditioning • Two entrances • Floor boxes • Grade II Listed building • LG7 lighting with indirect LED up-lighting • Fire and security system G R E A ET T THE TEA TRE E D S A BUILDING OL S T E R SHOREDITCH N S HOUSE OLD STREET T R E E T BOX PARK AD L RO NWEL SHOREDITCH CLERKE C I HIGH STREET T Y R G O O A S D W S F H A O E R L U A L R T AD T H I O R T R N A S STEPNEY D’ O O M AL G B N A GREEN P O D E D T H G O T O WHITECHAPEL A N N R R R O D BARBICAN W O CHANCERY E A FARRINGDON T N O LANE D T T E N H A E M C T N O C LBOR A D O HO M A IGH MOORGATE G B O H S R R U TOTTENHAM M L R LIVERPOOL P IC PE T LO E COURT ROAD NDON WA O K A LL R N R H STREET H C L C E E O S A I SPITALFIELDS I IT A A W B N H D L E W STE S R PNEY WAY T O J R U SALESFORCE A E HOLBORN B T D REE TOWER E ST N I D L XFOR E G T O W R E K G ES H ALDGATE I A H E N TE A O M LONDON MET. -

Mayor for London's Cycle Revolution

COMMITTEE DATE CLASSIFICATION REPORT NO. AGENDA nd ITEM NO. Cabinet 2 December Unrestricted (CAB 2009 086/090) REPORT OF TITLE Corporate Director (Communities, Localities & Mayor for London’s Cycle Revolution Culture) Wards Affected: All ORIGINATING OFFICER(S) Ashraf Ali, Project Manager Sustainable Initiatives Transportation & Highways 1.0 SUMMARY 1.1 The Mayor for London is progressing two key initiatives as part of his cycle Revolution for London. Both the London Cycle Hire Scheme and the Cycle Superhighways affect this borough and required the cooperation of the Council in their delivery. 1.2 This report appraises Members of the local details of the schemes and seeks approval to enter into an arrangement for the joint exercise of powers under section of 101 of the Local Government Act 1972 with Transport for London (TfL) to enable the installation of elements of these schemes. 2.0 RECOMMENDATIONS Cabinet is recommended to: 2.1 Note the proposals and ambitious timetables for the delivery of the TfL London Cycle Hire scheme & Cycle Superhighways scheme. 2.2 Authorise the Corporate Director Communities, Localities & Culture to approve an agreement between the Council and TfL for the joint exercise of functions to make temporary and permanent traffic regulation orders in respect of borough highways to facilitate the implementation and operation of the London Cycle Hire Scheme including the making of orders under sections 6 and 45 and the exercise of the powers in section 63 of that Act. 2.3 Note that the Council will enter into agreements with TfL pursuant to section 8 of the Highways Act 1980 in respect of works associated with the London Cycle LOCAL GOVERNMENT ACT, 1972 SECTION 100D (AS AMENDED) LIST OF BACKGROUND PAPERS USED IN THE PREPARATION OF THIS REPORT Brief description of background paper Name and telephone number of holder and address where open to inspection Way to Go – Mayor for London R Finch x2541 3.0 BACKGROUND 1 3.1 In May, the Mayor for London launched the Cycle Revolution for London. -

This Is a Truly Exceptional Penthouse Apartment

THIS IS A TRULY EXCEPTIONAL PENTHOUSE APARTMENT RATCLIFFE WHARF 18-22 NARROW STREET, E14 Guide Price £2,000,000, Share of Freehold THIS IS A TRULY EXCEPTIONAL PENTHOUSE APART MENT WITH UNINTERRUPTED VIEWS OF THE THAMES. IT OFFERS TWO BEDROOMS LAID OUT OVER TWO FLOORS WITH A SUPER SOUTH-FACING TERRACE RATCLIFFE WHARF, 18-22 NARROW STREET, E14 Guide Price £2,000,000, Share of Freehold A south-facing penthouse with views across the River Thames • Two bedrooms, both with en-suite • A sizeable reception room encompassing the kitchen • Offering a top floor roof terrace with built-in BBQ • Beautifully decorated • Basement storage 2 Bedrooms • 3 Bathrooms • 1 Reception EPC Rating = D Council Tax = G Situation The apartment is located on Narrow Street which runs parallel with the Thames. From here there are a number of pubs and restaurants with an enviable river location. Limehouse DLR is approximately 0.2 miles in distance taking you to Bank in less than 7 minutes and to Canary Wharf in less than 5. Canary Wharf can be accessed along the Thames Path and within a 15 minute walk. From here there is a multitude of restaurants and bars as well as five shopping malls. Description The main reception space extends to over 36" and has been thoughtfully designed to create a number of different areas including a dining space. The contemporary kitchen forms a sleek space with handless white gloss units as well as wall to ceiling cupboards. From the reception room there is access onto a balcony which sits on the corner of the building and stairs leading to the upstairs.