Aratus' Phaenomena Beyond Its Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Enthymema XXIII 2019 the Technê of Aratus' Leptê Acrostich

Enthymema XXIII 2019 The Technê of Aratus’ Leptê Acrostich Jan Kwapisz University of Warsaw Abstract – This paper sets out to re-approach the famous leptê acrostich in Aratus’ Phaenomena (783-87) by confronting it with other early Greek acrostichs and the discourse of technê and sophia, which has been shown to play an important role in a gamut of Greek literary texts, including texts very much relevant for the study of Aratus’ acrostich. In particular, there is a tantalizing connection between the acrostich in Aratus’ poem that poeticized Eudoxus’ astronomical work and the so- called Ars Eudoxi, a (pseudo-)Eudoxian acrostich sphragis from a second-century BC papyrus. Keywords – Aratus; Eudoxus; Ars Eudoxi; Acrostichs; Hellenistic Poetry; Technê; Sophia. Kwapisz, Jan. “The Technê of Aratus’ Leptê Acrostich.” Enthymema, no. XXIII, 2019, pp. 374-89. http://dx.doi.org/10.13130/2037-2426/11934 https://riviste.unimi.it/index.php/enthymema Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 Unported License ISSN 2037-2426 The Technê of Aratus’ Leptê Acrostich* Jan Kwapisz University of Warsaw To the memory of Cristiano Castelletti (1971-2017) Λεπτὴ μὲν καθαρή τε περὶ τρίτον ἦμαρ ἐοῦσα εὔδιός κ’ εἴη, λεπτὴ δὲ καὶ εὖ μάλ’ ἐρευθὴς πνευματίη· παχίων δὲ καὶ ἀμβλείῃσι κεραίαις 785 τέτρατον ἐκ τριτάτοιο φόως ἀμενηνὸν ἔχουσα ἠὲ νότου ἀμβλύνετ’ ἢ ὕδατος ἐγγὺς ἐόντος. (Arat. 783-87) If [the Moon is] slender and clear about the third day, she will bode fair weather; if slender and very red, wind; if the crescent is thickish, with blunted horns, having a feeble fourth-day light after the third day, either it is blurred by a southerly or because rain is in the offing. -

Scutum Apus Aquarius Aquila Ara Bootes Canes Venatici Capricornus Centaurus Cepheus Circinus Coma Berenices Corona Austrina Coro

Polaris Ursa Minor Cepheus Camelopardus Thuban Draco Cassiopeia Mizar Ursa Major Lacerta Lynx Deneb Capella Perseus Auriga Canes Venatici Algol Cygnus Vega Cor Caroli Andromeda Lyra Bootes Leo Minor Castor Triangulum Corona Borealis Albireo Hercules Pollux Alphecca Gemini Vulpecula Coma Berenices Pleiades Aries Pegasus Sagitta Arcturus Taurus Cancer Aldebaran Denebola Leo Delphinus Serpens [Caput] Regulus Equuleus Altair Canis Minor Pisces Betelgeuse Aquila Procyon Orion Serpens [Cauda] Ophiuchus Virgo Sextans Monoceros Mira Scutum Rigel Aquarius Spica Cetus Libra Crater Capricornus Hydra Sirius Corvus Lepus Deneb Kaitos Canis Major Eridanus Antares Fomalhaut Piscis Austrinus Sagittarius Scorpius Antlia Pyxis Fornax Sculptor Microscopium Columba Caelum Corona Austrina Lupus Puppis Grus Centaurus Vela Norma Horologium Phoenix Telescopium Ara Canopus Indus Crux Pictor Achernar Hadar Carina Dorado Tucana Circinus Rigel Kentaurus Reticulum Pavo Triangulum Australe Musca Volans Hydrus Mensa Apus SampleOctans file Chamaeleon AND THE LONELY WAR Sample file STAR POWER VOLUME FOUR: STAR POWER and the LONELY WAR Copyright © 2018 Michael Terracciano and Garth Graham. All rights reserved. Star Power, the Star Power logo, and all characters, likenesses, and situations herein are trademarks of Michael Terracciano and Garth Graham. Except for review purposes, no portion of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the express written consent of the copyright holders. All characters and events in this publication are fictional and any resemblance to real people or events is purely coincidental. Star chartsSample adapted from charts found at hoshifuru.jp file Portions of this book are published online at www.starpowercomic.com. This volume collects STAR POWER and the LONELY WAR Issues #16-20 published online between Oct 2016 and Oct 2017. -

The Magic of the Atwood Sphere

The magic of the Atwood Sphere Exactly a century ago, on June Dr. Jean-Michel Faidit 5, 1913, a “celestial sphere demon- Astronomical Society of France stration” by Professor Wallace W. Montpellier, France Atwood thrilled the populace of [email protected] Chicago. This machine, built to ac- commodate a dozen spectators, took up a concept popular in the eigh- teenth century: that of turning stel- lariums. The impact was consider- able. It sparked the genesis of modern planetariums, leading 10 years lat- er to an invention by Bauersfeld, engineer of the Zeiss Company, the Deutsche Museum in Munich. Since ancient times, mankind has sought to represent the sky and the stars. Two trends emerged. First, stars and constellations were easy, especially drawn on maps or globes. This was the case, for example, in Egypt with the Zodiac of Dendera or in the Greco-Ro- man world with the statue of Atlas support- ing the sky, like that of the Farnese Atlas at the National Archaeological Museum of Na- ples. But things were more complicated when it came to include the sun, moon, planets, and their apparent motions. Ingenious mecha- nisms were developed early as the Antiky- thera mechanism, found at the bottom of the Aegean Sea in 1900 and currently an exhibi- tion until July at the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in Paris. During two millennia, the human mind and ingenuity worked constantly develop- ing and combining these two approaches us- ing a variety of media: astrolabes, quadrants, armillary spheres, astronomical clocks, co- pernican orreries and celestial globes, cul- minating with the famous Coronelli globes offered to Louis XIV. -

Star Wheel Questions Set the Star Wheel for 9Pm on November 1St

Star Wheel Questions Set the star wheel for 9pm on November 1st. the edges of the star window are where the sky meets the ground. This is called the horizon. 1. What constellation is near the northern horizon? (Ursa Major, Bootes) 2. What constellation is near the eastern horizon? (Orion, Eridanus) The center of the star wheel is the top of the sky, over your head. 3. Name two constellations that are near the top of the sky. (Cassiopeia, Cepheus, Andromeda) On the star wheel, bigger stars appear brighter in the sky. 4. Which constellation would be easier to see because it has more bright stars: Cassiopeia or Cepheus? (Cassiopeia) 5. Planets are not shown on the star wheel. Why not? (because they change positions over time) Now set the star wheel for midnight on March 15. 6. Where in the sky would you look to see Canis Major? (near the western horizon) 7. Look toward the east. What constellation is about halfway between the horizon and the top of the sky in the east? (Corona Borealis (best answer) also Hercules, Bootes) The lines connecting the stars give us an idea about which stars belong to a constellation, and offer a pattern for us to look for in the sky. Each star pattern is supposed to represent a person, object or animal. For instance, Leo is supposed to be a lion. You also may have noticed that some constellations are bigger than others. 8. What constellation in the southern sky is the largest? (Hydra) 9. What is a small constellation in the southern sky? (Corvus, Canis Minor) 10. -

Circumpolar Constellations Educator's Guide (Ages 12-15)

Circumpolar Constellations Educator’s Guide (Ages 12-15) At the end of these Night Sky activities students will understand: • Why the constellations move in the sky • Many constellations rise over and set under the horizon • The circumpolar constellations are always above the horizon • Why Polaris is called the Pole Star Astronomy background information Accessible Learning: The Earth rotates on its axis every day. The Earth’s axis is the imaginary line • Text size can be increased in running between the north and south poles. The Earth’s movement means that the Preferences section our view of the sky changes over time. As the Earth rotates the positions of the constellations will change. Many constellations rise over the horizon, move across • Star numbers can be reduced the sky and set. However, some constellations do not rise and set and are visible by sliding two fingers down throughout the night. These are known as thecircumpolar constellations. the screen In the northern hemisphere, the starPolaris in the constellation of Ursa Minor is located in space almost exactly above the Earth’s North Pole. This means that Polaris does not seem to move as it is so close to the sky’s centre of rotation. For this reason Polaris is also known as the Pole Star or North Star. The circumpolar constellations are all located around Polaris in the sky. Different constellations will be circumpolar depending on your location but if you live in the northern hemisphere examples include Ursa Major, Ursa Minor, Cassiopeia, Draco, Cepheus and Camelopardalis. Night Sky App Essential Settings Go to Night Sky Settings and make sure the following Preferences are set. -

Supernova Star Maps

Supernova Star Maps Which Stars in the Night Sky Will Go Su pernova? About the Activity Allow visitors to experience finding stars in the night sky that will eventually go supernova. Topics Covered Observation of stars that will one day go supernova Materials Needed • Copies of this month's Star Map for your visitors- print the Supernova Information Sheet on the back. • (Optional) Telescopes A S A Participants N t i d Activities are appropriate for families Cre with children over the age of 9, the general public, and school groups ages 9 and up. Any number of visitors may participate. Location and Timing This activity is perfect for a star party outdoors and can take a few minutes, up to 20 minutes, depending on the Included in This Packet Page length of the discussion about the Detailed Activity Description 2 questions on the Supernova Helpful Hints 5 Information Sheet. Discussion can start Supernova Information Sheet 6 while it is still light. Star Maps handouts 7 Background Information There is an Excel spreadsheet on the Supernova Star Maps Resource Page that lists all these stars with all their particulars. Search for Supernova Star Maps here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov/download-search.cfm © 2008 Astronomical Society of the Pacific www.astrosociety.org Copies for educational purposes are permitted. Additional astronomy activities can be found here: http://nightsky.jpl.nasa.gov Star Maps: Stars likely to go Supernova! Leader’s Role Participants’ Role (Anticipated) Materials: Star Map with Supernova Information sheet on back Objective: Allow visitors to experience finding stars in the night sky that will eventually go supernova. -

SFA Star Chart 1

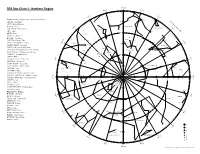

Nov 20 SFA Star Chart 1 - Northern Region 0h Dec 6 Nov 5 h 23 30º 1 h d Dec 21 h p Oct 21h s b 2 h 22 ANDROMEDA - Daughter of Cepheus and Cassiopeia Mirach Local Meridian for 8 PM q m ANTLIA - Air Pumpe p 40º APUS - Bird of Paradise n o i b g AQUILA - Eagle k ANDROMEDA Jan 5 u TRIANGULUM AQUARIUS - Water Carrier Oct 6 h z 3 21 LACERTA l h ARA - Altar j g ARIES - Ram 50º AURIGA - Charioteer e a BOOTES - Herdsman j r Schedar b CAELUM - Graving Tool x b a Algol Jan 20 b o CAMELOPARDALIS - Giraffe h Caph q 4 Sep 20 CYGNUS k h 20 g a 60º z CAPRICORNUS - Sea Goat Deneb z g PERSEUS d t x CARINA - Keel of the Ship Argo k i n h m a s CASSIOPEIA - Ethiopian Queen on a Throne c h CASSIOPEIA g Mirfak d e i CENTAURUS - Half horse and half man CEPHEUS e CEPHEUS - Ethiopian King Alderamin a d 70º CETUS - Whale h l m Feb 5 5 CHAMAELEON - Chameleon h i g h 19 Sep 5 i CIRCINUS - Compasses b g z d k e CANIS MAJOR - Larger Dog b r z CAMELOPARDALIS 7 h CANIS MINOR - Smaller Dog e 80º g a e a Capella CANCER - Crab LYRA Vega d a k AURIGA COLUMBA - Dove t b COMA BERENICES - Berenice's Hair Aug 21 j Feb 20 CORONA AUSTRALIS - Southern Crown Eltanin c Polaris 18 a d 6 d h CORONA BOREALIS - Northern Crown h q g x b q 30º 30º 80º 80º 40º 70º 50º 60º 60º 70º 50º CRATER - Cup 40º i e CRUX - Cross n z b Rastaban h URSA CORVUS - Crow z r MINOR CANES VENATICI - Hunting Dogs p 80º b CYGNUS - Swan h g q DELPHINUS - Dolphin Kocab Aug 6 e 17 DORADO - Goldfish q h h h DRACO o 7 DRACO - Dragon s GEMINI t t Mar 7 EQUULEUS - Little Horse HERCULES LYNX z i a ERIDANUS - River j -

Cassiopeia B1.Pdf

Cassiop eia Look in the northern part of the sky. You will see a pattern of stars a little like the letter W. This is the constellation Cassiopeia. Many people have told the story of Queen Cassiopeia. All of them tell about her great mistake. Here is one way her story has been told. Cassiopeia 2 There once was a queen named Cassiopeia. She was very proud of her beauty. She spent hours just looking at herself in her polished brass mirror. She would wear only lovely dresses. The queen’s servants worked hard to keep her hair pretty. One day the queen and her helpers walked along the ocean shore. When Cassiopeia saw her reflection in a pool of water, she was delighted. At that moment she said a very foolish thing. She said that she was more beautiful than even the daughters of Nereus, the god of the sea. Unfortunately for Cassiopeia, they heard her. 3 Nereus was a kindly god. Some called him the Old Man of the Sea. He had 50 daughters known as the Nereids. Cassiopeia’s words angered them all. The worst thing a person could do was to claim to be better than a god. Cassiopeia had insulted 50 of them with her boast. The Nereids went to their father. “Father, you must punish this woman!” they cried. “She has insulted us. She said she is more beautiful than us. No person should ever say they are better than a god. She must be punished!” Nereus, God of the Sea 4 Nereus did not wish to make waves about this, but he knew his daughters were right. -

Cassiopeia Constellation

Cassiopeia constellation Did you know? This constellation of stars is named after the vain queen Cassiopeia in Greek mythology, who used to tell everyone about how she was the most beautiful person of all! Bring the stars into your home! Ask an adult to help you cut around the dotted lines on the constellation. Try sticking your constellation onto thicker material to help block out the light. You could use thick card, foam or anything you have around the house, like tin foil. Grab a torch, or other light source, and shine the light at the paper onto your wall. Can you see the constellation? Hold an evening of stargazing story fun for your household. Choose a story to read that’s all about the night sky, or why not make up your own together about a journey through the stars? We created these fun resources with our friends at the Royal Astronomical Society. If you’re inspired to find out more about our night sky, check out their website for lots of fun information and resources: ras.ac.uk Cepheus constellation Did you know? This constellation of stars is named after Cepheus, a king of Aethiopia in Greek mythology. He was married to Cassiopeia and is the father of Andromeda, who named a very famous galaxy which is approximately 2.5 million light years away from Earth! Bring the stars into your home! Ask an adult to help you cut around the dotted lines on the constellation. Try sticking your constellation onto thicker material to help block out the light. -

Guide to the Constellations

STAR DECK GUIDE TO THE CONSTELLATIONS BY MICHAEL K. SHEPARD, PH.D. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction 1 Constellations by Season 3 Guide to the Constellations Andromeda, Aquarius 4 Aquila, Aries, Auriga 5 Bootes, Camelopardus, Cancer 6 Canes Venatici, Canis Major, Canis Minor 7 Capricornus, Cassiopeia 8 Cepheus, Cetus, Coma Berenices 9 Corona Borealis, Corvus, Crater 10 Cygnus, Delphinus, Draco 11 Equuleus, Eridanus, Gemini 12 Hercules, Hydra, Lacerta 13 Leo, Leo Minor, Lepus, Libra, Lynx 14 Lyra, Monoceros 15 Ophiuchus, Orion 16 Pegasus, Perseus 17 Pisces, Sagitta, Sagittarius 18 Scorpius, Scutum, Serpens 19 Sextans, Taurus 20 Triangulum, Ursa Major, Ursa Minor 21 Virgo, Vulpecula 22 Additional References 23 Copyright 2002, Michael K. Shepard 1 GUIDE TO THE STAR DECK Introduction As an introduction to astronomy, you cannot go wrong by first learning the night sky. You only need a dark night, your eyes, and a good guide. This set of cards is not designed to replace an atlas, but to engage your interest and teach you the patterns, myths, and relationships between constellations. They may be used as “field cards” that you take outside with you, or they may be played in a variety of card games. The cultural and historical story behind the constellations is a subject all its own, and there are numerous books on the subject for the curious. These cards show 52 of the modern 88 constellations as designated by the International Astronomical Union. Many of them have remained unchanged since antiquity, while others have been added in the past century or so. The majority of these constellations are Greek or Roman in origin and often have one or more myths associated with them. -

The Phenomena and Diosemeia of Aratus

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS 0002035357^ Qass-TA 3 87 3 " Book- A £ 4 164-8 THE PHENOMENA AND DIOSEMEIA A RAT US $3r(ntetr at tije SEniDersttj $ress. 4 \ : THE PHENOMENA AND DIOSEMEIA OF ARATUS, TRANSLATED INTO ENGLISH VERSE, WITH NOTES, BY JOHN LAMB, D.D. MASTER OF CORPUS CHRISTI COLLEGE, CAMBRIDGE, AND DEAN OF BRISTOL. UavO' 'Hyrjcnava^ re kcli 'Epfiimros ra Kar aldprjv Tetpea, Kai 7roXXot ravra cpaivo/xeva Bt/3Xois iyKaredevTO' aixoaKOTTioL §' dcpapaprow AAAA TO AEIITOAOrOY 2KHHTPON APAT02 EXEI. LONDON JOHN W. PARKER, WEST STRAND. M.DCCC.XLVIII. Page 40, line 200, for Cythia read Cynthia. THE LIFE OF ARATUS, WHEN Cilicia, in the days of Cicero*, boasted of being the birth-place of the Poet Aratus, there was reserved for her a far higher honour, the giving birth to one of the noblest of mankind, if true nobility consist in the power of benefiting the human race, and in the exercise of that power to the greatest extent by the most unexampled self-denial. Soli, the native city of Aratus, was not far distant from Tarsus, the birth-place of St Paul; and the fame of the heathen Poet has been considerably enhanced by a passage from his writings having been quoted by his countryman, the christian Apostle. One biographer indeed states that Aratus was a native of Tarsus, and he is occasionally called Tarsensis; but the more probable opinion is, that he was born at Soli, and he is commonly called Solensis. The date of his birth is about 260 years before the Christian sera. The names of his parents were Athedonorus and Letophila, they were persons of some conse- * Cicero was Proconsul of Cilicia a. -

Download File

Cicero Among the Stars: Natural Philosophy and Astral Culture at Rome Ashley Ariel Simone Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy under the Executive Committee of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY 2020 © 2020 Ashley A. Simone All Rights Reserved ABSTRACT Cicero Among the Stars: Natural Philosophy and Astral Culture at Rome Ashley Ariel Simone This dissertation examines Cicero’s contribution to the rise of astronomy and astrology in the literary and cultural milieu of the late Republic and early Empire. Chapter One, “Rome’s Star Poet,” examines how Cicero conceives of world building through words to connect Rome to the stars with the Latin language. Through a close study of the Aratea, I consider how Cicero’s pioneering of Latin astronomical language influenced other writers, especially his contemporaries Lucretius and Catullus. In Chapter Two, “The Stars and the Statesman,” I examine Cicero’s attitudes towards politics. By analyzing Scipio’s Dream and astronomy in De re publica, I show how Cicero uses cosmic models to yoke Rome to the stars. To understand the astral dimensions of Cicero’s philosophy, in Chapter Three, “Signs and Stars, Words and Worlds,” I provide a close reading of Cicero’s poetic quotations in context in the De natura deorum and De divinatione to show how Cicero puts the Aratean cosmos to the test in Academic fashion. Ultimately, I argue that Cicero profoundly shaped the Roman view of the stars and cemented the link between cosmos and empire.