1 Stirringly Combining Ambition and Alliteration

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Production Notes for Feature Film, “Snow Cake” It's April 2005 and The

Production Notes for Feature Film, “Snow Cake” It’s April 2005 and the snow is melting fast in Wawa there is perceptible panic throughout the cast and crew of Snow Cake when they find out that this location chosen specifically for its customary frigid climate and overabundance of snow – has very little snow to speak of. “The reason we went to Wawa in the first place was to get the snow, says director Marc Evans with a smile. “I was very worried about not getting enough snow. And then Alan Rickman, who plays Alex, said ‘Look, at the end of the day, this film is not about snow. It’s got snow in the title, but it’s about the people who live in this place.’ And I thought, yes, that’s so true. It’s the interaction between the two main characters that forms the thrust of the film. The joy of this film is seeing how the characters interact.” In fact, the lack of snow may have been a blessing in disguise for the film. ‘It appears that this film is being guided by some unseen force in a way,” Rickman says. “We went to Wawa a week later than we were due to. Had we gone there the week before, we would have encountered temperatures that would have been so horrific to work in, so cold, below freezing” Instead, “we had a freak period of 13 days of unbroken sunshine, which on the face of it, with a film called Snow Cake, you might think would be a problem!” But Rickman had always said that the film would find itself and it did in the most beautiful way as the snow thawed around them. -

On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau

Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau To cite this version: Philippe Laplace, Eric Tabuteau. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities. Representation of Urban Space in Contemporary Irish and British Fiction. 2003. hal-02320291 HAL Id: hal-02320291 https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02320291 Submitted on 14 Nov 2020 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities 7 TABLE OF CONTENTS Gérard BREY (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Foreword ..... 9 Philippe LAPLACE & Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche- Comté, Besançon), Cities on the Margin; On the Margin of Cities ......... 11 Richard SKEATES (Open University), "Those vast new wildernesses of glass and brick:" Representing the Contemporary Urban Condition ......... 25 Peter MILES (University of Wales, Lampeter), Road Rage: Urban Trajectories and the Working Class ............................................................ 43 Tim WOODS (University of Wales, Aberystwyth), Re-Enchanting the City: Sites and Non-Sites in Urban Fiction ................................................ 63 Eric TABUTEAU (University of Franche-Comté, Besançon), Marginally Correct: Zadie Smith's White Teeth and Sam Selvon's The Lonely Londoners .................................................................................... -

John Simm ~ 47 Screen Credits and More

John Simm ~ 47 Screen Credits and more The eldest of three children, actor and musician John Ronald Simm was born on 10 July 1970 in Leeds, West Yorkshire and grew up in Nelson, Lancashire. He attended Edge End High School, Nelson followed by Blackpool Drama College at 16 and The Drama Centre, London at 19. He lives in North London with his wife, actress Kate Magowan and their children Ryan, born on 13 August 2001 and Molly, born on 9 February 2007. Simm won the Best Actor award at the Valencia Film Festival for his film debut in Boston Kickout (1995) and has been twice BAFTA nominated (to date) for Life On Mars (2006) and Exile (2011). He supports Man U, is "a Beatles nut" and owns seven guitars. John Simm quotes I think I can be closed in. I can close this outer shell, cut myself off and be quite cold. I can cut other people off if I need to. I don't think I'm angry, though. Maybe my wife would disagree. I love Manchester. I always have, ever since I was a kid, and I go back as much as I can. Manchester's my spiritual home. I've been in London for 22 years now but Manchester's the only other place ... in the country that I could live. You never undertake a project because you think other people will like it - because that way lies madness - but rather because you believe in it. Twitter has restored my faith in humanity. I thought I'd hate it, but while there are lots of knobheads, there are even more lovely people. -

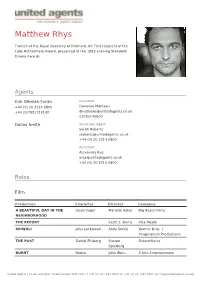

Matthew Rhys

Matthew Rhys Trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art First recipient of the Lady Rothermere Award, presented at the 1993 Evening Standard Drama Awards Agents Kirk Whelan-Foran Assistant +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Donovan Mathews +44 (0)7920713142 [email protected] 02032140800 Dallas Smith Associate Agent Sarah Roberts [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Assistant Alexandra Rae [email protected] +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 Roles Film Production Character Director Company A BEAUTIFUL DAY IN THE Lloyd Vogel Marielle Heller Big Beach Films NEIGHBORHOOD THE REPORT Scott Z. Burns Vice Media MOWGLI John Lockwood Andy Serkis Warner Bros. | Imaginarium Productions THE POST Daniel Ellsberg Steven DreamWorks Spielberg BURNT Reece John Wells 3 Arts Entertainment United Agents | 12-26 Lexington Street London W1F OLE | T +44 (0) 20 3214 0800 | F +44 (0) 20 3214 0801 | E [email protected] Production Character Director Company THE SCAPEGOAT John Charles Island Pictures Sturridge LUSTER Joseph Miller ADAM MASON Azurelight Pictures PATAGONIA Mateo Marc Evans Rainy Day Films ABDUCTION CLUB Strang Steven Schwartz Pathe DEATHWATCH Doc M.J. Bassett Pathe FAKERS Nick Blake Richard Janes Faking It Productions COME WHAT MAY Percy Christian Carion Nord-Ouest Productions GUILTY PLEASURES Count David Leland Boccaccio Productions Dzerzhinsky HEART Sean Charles Granada McDougal HOUSE OF AMERICA Boyo Marc Evans September Films LOVE AND OTHER DISASTERS Peter Simon Alek Keshishian Skyline Ltd PAVAROTTI IN DAD'S ROOM Nob Sara Sugarman Dragon -

Childhood Choice…

06/02/2015 And the winner is…The Theory of Everything and The Imitation Game Whether or not they win a BAFTA the main locations for this year’s two leading BAFTA contenders are already winners in terms of house price rises To coincide with the 2015 BAFTA awards on Sunday 8 February, Halifax looked at the house prices in the main locations for 20 major UK films to see who’s scooped the gong for best performance and who’s picked up the award for best supporting role. In the past five years house prices around where this year’s two main contenders for film awards were set saw the biggest house prices rises of all 20 locations analysed. Prices in Cambridge (The Theory of Everything) have risen 26% and prices in Milton Keynes (The Imitation Game) have gone up 25%. Having a film associated with where you live is no guarantee of high house prices though as while both top performers have seen prices rise by more than their regional averages since 2009 only seven of the 20 locations analysed have done the same [Table 1]. House price rises in film locations over the last 10 years (2004-2014) 1983 classic Local Hero, which was largely filmed in Aberdeenshire, has been the strongest performing film location over the past ten years. The 86% rise in house prices largely reflects the strength of the local oil and gas based economy, which was featured in the film. Both The Theory of Everything (39%) and The Imitation Game (26%) again feature in the top five. -

Patagonian Road Movies and Migration from Wales

I D E N T I D A D E S Núm. 5, Año 3 Diciembre 2013 pp. 131-136 ISSN 2250-5369 Patagonian road movies and migration from Wales Esther Whitfield1 Abstract This paper analyzes two recent films, Patagonia (2011) and Separado! (2010), both produced in Wales and set in Patagonia. It proposes that both take advantage of the codes and tropes of the road movie genre, and of the history of Welsh emigration to Patagonia, to situate Welsh language and culture in both a local and global context. Key Words Wales - Patagonia - road movie - emigration. Las road movies patagónicas y la migración desde Gales Resumen Este trabajo analiza dos películas recients, Patagonia (2011) y Separado!(2010), ambas producidas en Gales y escenificadas en la Patagonia. Propone que ambas se aprovechan de los códigos y tropos de la “road movie” y de la historia de emigración galesa a la Patagonia, para ubicar la cultura y lengua galesas en un contexto que es a la vez local y global. Palabras claves Gales - Patagonia - road movie - migración 1 Associate Professor of Comparative Literature, Brown University, Providence, Rhode Island, Estados Unidos. [email protected]. WHITFIELD PATAGONIAN ROAD MOVIES AND MIGRATION FROM WALES “The driving force propelling most road movies,” writes David Laderman, “is an embrace of the journey as a means of cultural critique” (Laderman 2002, 1). In the light of this analysis, this essay begins with two questions: in what ways might Patagonia lend itself- as setting, as landscape, as historically preconceived idea - to the road movie? And how do road movies set in Patagonia intersect with a history of immigrant travel to the region, specifically in the case of the storied nineteenth- century Welsh immigration to Chubut and the Esquel/ Trevelin area? My focus here is two bilingual (Spanish-Welsh) films, Patagonia and Separado!, released in 2011 and 2010 respectively in a context of much cultural production – in the form of novels, documentaries, radio programs etc. -

PRESS Graphic Designer

© 2021 MARVEL CAST Natasha Romanoff /Black Widow . SCARLETT JOHANSSON Yelena Belova . .FLORENCE PUGH Melina . RACHEL WEISZ Alexei . .DAVID HARBOUR Dreykov . .RAY WINSTONE Young Natasha . .EVER ANDERSON MARVEL STUDIOS Young Yelena . .VIOLET MCGRAW presents Mason . O-T FAGBENLE Secretary Ross . .WILLIAM HURT Antonia/Taskmaster . OLGA KURYLENKO Young Antonia . RYAN KIERA ARMSTRONG Lerato . .LIANI SAMUEL Oksana . .MICHELLE LEE Scientist Morocco 1 . .LEWIS YOUNG Scientist Morocco 2 . CC SMIFF Ingrid . NANNA BLONDELL Widows . SIMONA ZIVKOVSKA ERIN JAMESON SHAINA WEST YOLANDA LYNES Directed by . .CATE SHORTLAND CLAUDIA HEINZ Screenplay by . ERIC PEARSON FATOU BAH Story by . JAC SCHAEFFER JADE MA and NED BENSON JADE XU Produced by . KEVIN FEIGE, p.g.a. LUCY JAYNE MURRAY Executive Producer . LOUIS D’ESPOSITO LUCY CORK Executive Producer . VICTORIA ALONSO ENIKO FULOP Executive Producer . BRAD WINDERBAUM LAUREN OKADIGBO Executive Producer . .NIGEL GOSTELOW AURELIA AGEL Executive Producer . SCARLETT JOHANSSON ZHANE SAMUELS Co-Producer . BRIAN CHAPEK SHAWARAH BATTLES Co-Producer . MITCH BELL TABBY BOND Based on the MADELEINE NICHOLLS MARVEL COMICS YASMIN RILEY Director of Photography . .GABRIEL BERISTAIN, ASC FIONA GRIFFITHS Production Designer . CHARLES WOOD GEORGIA CURTIS Edited by . LEIGH FOLSOM BOYD, ACE SVETLANA CONSTANTINE MATTHEW SCHMIDT IONE BUTLER Costume Designer . JANY TEMIME AUBREY CLELAND Visual Eff ects Supervisor . GEOFFREY BAUMANN Ross Lieutenant . KURT YUE Music by . LORNE BALFE Ohio Agent . DOUG ROBSON Music Supervisor . DAVE JORDAN Budapest Clerk . .ZOLTAN NAGY Casting by . SARAH HALLEY FINN, CSA Man In BMW . .MARCEL DORIAN Second Unit Director . DARRIN PRESCOTT Mechanic . .LIRAN NATHAN Unit Production Manager . SIOBHAN LYONS Mechanic’s Wife . JUDIT VARGA-SZATHMARY First Assistant Director/ Mechanic’s Child . .NOEL KRISZTIAN KOZAK Associate Producer . -

Films & Major TV Dramas Shot (In Part Or Entirely) in Wales

Films & Major TV Dramas shot (in part or entirely) in Wales Feature films in black text TV Drama in blue text Historical Productions (before the Wales Screen Commission began) Dates refer to when the production was released / broadcast. 1935 The Phantom Light - Ffestiniog Railway and Lleyn Peninsula, Gwynedd; Holyhead, Anglesey; South Stack Gainsborough Pictures Director: Michael Powell Cast: Binnie Hale, Gordon Harker, Donald Calthrop 1938 The Citadel - Abertillery, Blaenau Gwent; Monmouthshire Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer British Studios Director: King Vidor Cast: Robert Donat, Rosalind Russell, Ralph Richardson 1940 The Thief of Bagdad - Freshwater West, Pembrokeshire (Abu & Djinn on the beach) Directors: Ludwig Berger, Michael Powell The Proud Valley – Neath Port Talbot; Rhondda Valley, Rhondda Cynon Taff Director: Pen Tennyson Cast: Paul Robeson, Edward Chapman 1943 Nine Men - Margam Sands, Neath, Neath Port Talbot Ealing Studios Director: Harry Watt Cast: Jack Lambert, Grant Sutherland, Gordon Jackson 1953 The Red Beret – Trawsfynydd, Gwynedd Director: Terence Young Cast: Alan Ladd, Leo Genn, Susan Stephen 1956 Moby Dick - Ceibwr Bay, Fishguard, Pembrokeshire Director: John Huston Cast: Gregory Peck, Richard Basehart 1958 The Inn of the Sixth Happiness – Snowdonia National Park, Portmeirion, Beddgelert, Capel Curig, Cwm Bychan, Lake Ogwen, Llanbedr, Morfa Bychan Cast: Ingrid Bergman, Robert Donat, Curd Jürgens 1959 Tiger Bay - Newport; Cardiff; Tal-y-bont, Cardigan The Rank Organisation / Independent Artists Director: J. Lee Thompson Cast: -

Mali Evans Editor

Shepperton Studios, Studios Road, Shepperton, Middx, TW17 OQD Tel: +44 (0)1932 571044 Website: www.saraputt.co.uk Mali Evans Editor TV Drama THE ENGLISH GAME 42 Management Production for Exec: Rory Aitken 6x60' NETFLIX Exec: Julian Fellowes Prod: Rhonda Smith Prod: Andy Morgan Dir: Brigitta Staermose JERUSALEM 42 Prod: Rhonda Smith Episodes 4, 5 & 6 Dir: Alex Winckler Dir: Dearbhla Walsh BANG Joio TV Prod: Catrin Lewis Defis Episodes 3 & 4 Dir: Ashley Way HINTERLAND/Y GWYLL Fiction Factory Prod: Gethin Scourfield Series II Prod: Ed Talfan Various Episodes HINTERLAND/Y GWYLL Fiction Factory Prod: Gethin Scourfield, Ed Talfan Series I Dir: Marc Evans, Rhys Powys Various Episodes DOORS OPEN Sprout Pictures Prod: Jon Finn TV Movie Dir: Marc Evans 1x120mins SHERLOCK Hartswood Films Prod: Sue Vertue Series I Dir: Euros Lyn 1x90mins Episode 2 - 'The Blind Banker' Winner: Televisual Bulldog Award for Best Editor AR Y TRACS Tidy Productions / Green Bay Media Prod: David Peet TV Movie Dir: Ed Talfan TIPYN O STAD Tonfedd / Eryri Production Prod: Pauline Williams Series I - VII Bafta Nominated Drama Series GWYFYN Fiction Factory Dir: Euros Lyn BAFTA award winning drama DIWRNOD HOLLOL MINDBLOWING HTV Dir: Euros Lyn HEDDIW BAFTA Nominated Drama YR ADUNIAD Boda Productions Dir: Ceri Sherlock TV Movie BAFTA Nomination for Best Editor NOSON YR HELIWR Back to Back Productions Dir: Peter Edwards TV Movie BAFTA winner for Best Editor Page 1 of 2 JERUSALEM 42 Dir: Rhonda Smith Editor Dir: Alex Winckler Episodes 4,5 & 6 Prod: Rhonda Smith Features THAT GOOD NIGHT -

A History of the Welsh English Dialect in Fiction

_________________________________________________________________________Swansea University E-Theses A History of the Welsh English Dialect in Fiction Jones, Benjamin A. How to cite: _________________________________________________________________________ Jones, Benjamin A. (2018) A History of the Welsh English Dialect in Fiction. Doctoral thesis, Swansea University. http://cronfa.swan.ac.uk/Record/cronfa44723 Use policy: _________________________________________________________________________ This item is brought to you by Swansea University. Any person downloading material is agreeing to abide by the terms of the repository licence: copies of full text items may be used or reproduced in any format or medium, without prior permission for personal research or study, educational or non-commercial purposes only. The copyright for any work remains with the original author unless otherwise specified. The full-text must not be sold in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder. Permission for multiple reproductions should be obtained from the original author. Authors are personally responsible for adhering to copyright and publisher restrictions when uploading content to the repository. Please link to the metadata record in the Swansea University repository, Cronfa (link given in the citation reference above.) http://www.swansea.ac.uk/library/researchsupport/ris-support/ A history of the Welsh English dialect in fiction Benjamin Alexander Jones Submitted to Swansea University in fulfilment of the requirements -

Componend-Based Deductive Verification of Cyber-Physical

Submitted by Andreas M¨uller Submitted at Department of Cooperative Information Systems Supervisor and First Examiner Wieland Schwinger Second Examiner Component-based Andr´ePlatzer Co-Supervisor Deductive Verification of Stefan Mitsch Cyber-physical Systems October 2017 Doctoral Thesis to obtain the academic degree of Doktor der technischen Wissenschaften in the Doctoral Program Technische Wissenschaften JOHANNES KEPLER UNIVERSITY LINZ Altenbergerstraße 69 4040 Linz, Osterreich¨ www.jku.at DVR 0093696 To Katrin – that much. Eidesstattliche Erkl¨arung Ich erkl¨arean Eides statt, dass ich die vorliegende Dissertation selbstst¨andigund ohne fremde Hilfe verfasst, andere als die angegebenen Quellen und Hilfsmittel nicht benutzt bzw. die w¨ortlich oder sinngem¨aßentnommenen Stellen als solche kenntlich gemacht habe. Die vorliegende Dissertation ist mit dem elektronisch ¨ubermittelten Textdokument identisch. v Acknowledgements First of all and most importantly, I want to thank my beloved wife Katrin: Without you, all this would have been impossible! Thank you for your repeated encouragement and your almost endless patience, especially over the last 5 years. Furthermore, I want to thank my parents Klaus and Gertrude, my brother Daniel, my grandparents Karl and Rosi, and my parents-in-law Karl and Gundi. Thank you for your ongoing support and for always believing in me. During my time as a doctoral candidate I had the pleasure of meeting nu- merous further inspiring people from all over the world. I want to thank all of you, for making this time of my life so special. Many thanks to my supervisors in Linz, Wieland Schwinger and Werner Retschitzegger, for your support and the countless fruitful discussions. -

Magic in the Moonlight

Sony Pictures Classics Presents in association with Gravier Productions, Inc. A Dippermouth Production in association with Perdido Productions & Ske-Dat-De-Dat Productions Magic in the Moonlight Written and Directed by Woody Allen East Coast Publicity West Coast Publicity Distributor 42West Block Korenbrot Sony Pictures Classics Scott Feinstein Max Buschman Carmelo Pirrone 220 West 42nd Street 110 S. Fairfax Ave, #310 Maya Anand 12th floor Los Angeles, CA 90036 550 Madison Ave New York, NY 10036 323-634-7001 tel New York, NY 10022 212-277-7555 323-634-7030 fax 212-833-8833 tel 212-833-8844 fax MAGIC IN THE MOONLIGHT Starring (in alphabetical order) Aunt Vanessa EILEEN ATKINS Stanley COLIN FIRTH Mrs. Baker MARCIA GAY HARDEN Brice HAMISH LINKLATER Howard Burkan SIMON McBURNEY Sophie EMMA STONE Grace JACKI WEAVER Co-starring (in alphabetical order) Caroline ERICA LEERHSEN Olivia CATHERINE McCORMACK George JEREMY SHAMOS Filmmakers Writer/Director WOODY ALLEN Producers LETTY ARONSON, p.g.a. STEPHEN TENENBAUM, p.g.a. EDWARD WALSON, p.g.a. Co-Producers HELEN ROBIN RAPHAËL BENOLIEL Executive Producer RONALD L. CHEZ Co-Executive Producer JACK ROLLINS Director of Photography DARIUS KHONDJI A.S.C., A.F.C Production Designer ANNE SEIBEL, ADC Editor ALISA LEPSELTER A.C.E. Costume Design SONIA GRANDE Casting JULIET TAYLOR PATRICIA DICERTO 2 MAGIC IN THE MOONLIGHT Synopsis Set in the 1920s on the opulent Riviera in the south of France, Woody Allen’s MAGIC IN THE MOONLIGHT is a romantic comedy about a master magician (Colin Firth) trying to expose a psychic medium (Emma Stone) as a fake.