Capital, Cooperation and Creating Performance: Bloodwater Theatre Develops Ownership in Collaborative Theatre Practice

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Commercial & Artistic Viability of the Fringe Movement

Rowan University Rowan Digital Works Theses and Dissertations 1-13-2013 The commercial & artistic viability of the fringe movement Charles Garrison Follow this and additional works at: https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Garrison, Charles, "The commercial & artistic viability of the fringe movement" (2013). Theses and Dissertations. 490. https://rdw.rowan.edu/etd/490 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Rowan Digital Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Rowan Digital Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE COMMERCIAL & ARTISTIC VIABLILITY OF THE FRINGE MOVEMENT By Charles J. Garrison A Thesis Submitted to the Department of Theatre & Dance College of Performing Arts In partial fulfillment of the requirement For the degree of Master of Arts At Rowan University December 13, 2012 Thesis Chair: Dr. Elisabeth Hostetter © 2012 Charles J. Garrison Dedication I would like to dedicate this to my drama students at Absegami High School, to my mother, Rosemary who’s wish it was that I finish this work, and to my wife, Lois and daughter, Colleen for pushing me, loving me, putting up with me through it all. Acknowledgements I would like to express my appreciation to Jason Bruffy and John Clancy for the inspiration as artists and theatrical visionaries, to the staff of the American High School Theatre Festival for opening the door to the Fringe experience for me in Edinburgh, and to Dr. Elisabeth Hostetter, without whose patience and guidance this thesis would ever have been written. -

3/30/2021 Tagscanner Extended Playlist File:///E:/Dropbox/Music For

3/30/2021 TagScanner Extended PlayList Total tracks number: 2175 Total tracks length: 132:57:20 Total tracks size: 17.4 GB # Artist Title Length 01 *NSync Bye Bye Bye 03:17 02 *NSync Girlfriend (Album Version) 04:13 03 *NSync It's Gonna Be Me 03:10 04 1 Giant Leap My Culture 03:36 05 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Jucxi So Confused 03:35 06 2 Play Feat. Raghav & Naila Boss It Can't Be Right 03:26 07 2Pac Feat. Elton John Ghetto Gospel 03:55 08 3 Doors Down Be Like That 04:24 09 3 Doors Down Here Without You 03:54 10 3 Doors Down Kryptonite 03:53 11 3 Doors Down Let Me Go 03:52 12 3 Doors Down When Im Gone 04:13 13 3 Of A Kind Baby Cakes 02:32 14 3lw No More (Baby I'ma Do Right) 04:19 15 3OH!3 Don't Trust Me 03:12 16 4 Strings (Take Me Away) Into The Night 03:08 17 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot 03:12 18 5 Seconds of Summer Youngblood 03:21 19 50 Cent Disco Inferno 03:33 20 50 Cent In Da Club 03:42 21 50 Cent Just A Lil Bit 03:57 22 50 Cent P.I.M.P. 04:15 23 50 Cent Wanksta 03:37 24 50 Cent Feat. Nate Dogg 21 Questions 03:41 25 50 Cent Ft Olivia Candy Shop 03:26 26 98 Degrees Give Me Just One Night 03:29 27 112 It's Over Now 04:22 28 112 Peaches & Cream 03:12 29 220 KID, Gracey Don’t Need Love 03:14 A R Rahman & The Pussycat Dolls Feat. -

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland

Media Culture for a Modern Nation? Theatre, Cinema and Radio in Early Twentieth-Century Scotland a study © Adrienne Clare Scullion Thesis submitted for the degree of PhD to the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Faculty of Arts, University of Glasgow. March 1992 ProQuest Number: 13818929 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 13818929 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 Frontispiece The Clachan, Scottish Exhibition of National History, Art and Industry, 1911. (T R Annan and Sons Ltd., Glasgow) GLASGOW UNIVERSITY library Abstract This study investigates the cultural scene in Scotland in the period from the 1880s to 1939. The project focuses on the effects in Scotland of the development of the new media of film and wireless. It addresses question as to what changes, over the first decades of the twentieth century, these two revolutionary forms of public technology effect on the established entertainment system in Scotland and on the Scottish experience of culture. The study presents a broad view of the cultural scene in Scotland over the period: discusses contemporary politics; considers established and new theatrical activity; examines the development of a film culture; and investigates the expansion of broadcast wireless and its influence on indigenous theatre. -

Scotland: BBC Weeks 51 and 52

BBC WEEKS 51 & 52, 18 - 31 December 2010 Programme Information, Television & Radio BBC Scotland Press Office bbc.co.uk/pressoffice bbc.co.uk/iplayer THIS WEEK’S HIGHLIGHTS TELEVISION & RADIO / BBC WEEKS 51 & 52 _____________________________________________________________________________________________________ MONDAY 20 DECEMBER The Crash, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland TUESDAY 21 DECEMBER River City TV HIGHLIGHT BBC One Scotland WEDNESDAY 22 DECEMBER How to Make the Perfect Cake, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland THURSDAY 23 DECEMBER Pioneers, Prog 1/5 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Scotland on Song …with Barbara Dickson and Billy Connolly, NEW BBC Radio Scotland FRIDAY 24 DECEMBER Christmas Celebration, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC One Scotland Brian Taylor’s Christmas Lunch, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Watchnight Service, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland A Christmas of Hope, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland SATURDAY 25 DECEMBER Stark Talk Christmas Special with Fran Healy, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland On the Road with Amy MacDonald, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Stan Laurel’s Glasgow, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Christmas Classics, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland SUNDAY 26 DECEMBER The Pope in Scotland, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC One Scotland MONDAY 27 DECEMBER Best of Gary:Tank Commander TV HIGHLIGHT BBC One Scotland The Hebridean Trail, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Two Scotland When Standing Stones, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland Another Country Legends with Ricky Ross, Prog 1/1 NEW BBC Radio Scotland TUESDAY 28 DECEMBER River City TV HIGHLIGHT -

British Theatre: Volume 3: Since 1895 Edited by Baz Kershaw Frontmatter More Information

Cambridge University Press 978-1-107-49709-2 - The Cambridge History of British Theatre: Volume 3: Since 1895 Edited by Baz Kershaw Frontmatter More information the cambridge history of BRITISH THEATRE * volume 3 Since 1895 This volume explores the rich and complex histories of English, Scottish and Welsh theatres in the ‘long’ twentieth century since 1895.Twenty-three original essays by leading historians and critics investigate the major aspects of theatrical performance, ranging from the great actor-managers to humble seaside entertainers, from between-wars West End women playwrights to the roots of professional theatre in Walesand Scotland, and from the challenges of alternative theatres to the economics of theatre under Thatcher. Detailed surveys of key theatre practices and traditions across this whole period are combined with case studies of influential produc- tions, critical years placed in historical perspective and evaluations of theatre at the turn of the millennium. The collection presents an exciting evolution in the scholarly study of modern British the- atre history, skilfully demonstrating how performance variously became a critical litmus test of the great aesthetic, cultural, social, political and economic upheavals in the age of extremes. Baz Kershaw is Chair of Drama at the Department of Drama, University of Bristol. He is the author of ThePolitics of Performance: Radical Theatre as Cultural Intervention (1992) and The Radical in Performance: Between Brecht and Baudrillard (1999), and has published in many journals -

QMUC RR 2002Bb

Contents Contents 1 Preface 3 Report 2002 Research Introduction 4-5 Speech and Language Sciences Research Area 7 Physical Therapy Research Area 29 Social Sciences in Health Research Area 53 Nutrition and Food Research Area 81 Business and Management Research Area 95 Information Management Research Area 111 Media and Communication Research Area 119 Drama Research Area 133 Queen Margaret University College Research Report 2002 1 Research Report 2002 Research 2 Queen Margaret University College Research Report 2002 Research Report 2002 Research Preface Our Research Report for 2000-2002 reflects an outstanding level of achievement throughout the institution and demonstrates once again our high level of commitment to strategic and applied research particularly in areas that enhance the quality of life. Since our last report in 2000 the RAE results have been published and our achievements reflect an increase in both the quality of our research outputs and also the diversity and range of research undertaken. In RAE 2001 we returned 43% of all our staff as research active which was amongst the highest in the new university sector across the UK. We were also pleased that four of our Research Areas submitted (Speech and Language Sciences, Social Sciences in Health, Physical Therapy and Drama) achieved an improved grade from the last RAE resulting in an overall 27% increase in income compared with our previous allocation. We are increasingly developing our strategies for the commercialisation of research and this is reflected in a significant increase in our CPD activities, the growth of our TCS programmes and successful spin out companies. Research and commercial activities cover a wide variety from highly focused consultancy for external organisations, including leading UK corporate businesses, the NHS, charities and government departments, to definitive academic studies which have won staff international reputations through their publications and presentations at conferences in the UK and abroad. -

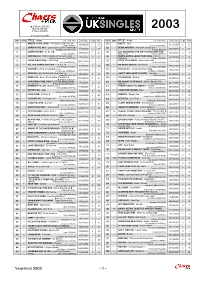

Chartsplus YE2003

p Platinum (600,000) ä Gold (400,000) 2003 è Silver (200,000) ² Former FutureHIT 2003 2002 TITLE - Artist Label (Cat. No.) Entry Date High Wks 2003 2002 TITLE - Artist Label (Cat. No.) Entry Date High Wks p 6 1 -- WHERE IS THE LOVE? - The Black Eyed Peas 13/09/2003 1 17 51 -- GUILTY - Blue 01/11/2003 2 10 A&M (9810996) Innocent (SINCD51) p 2 2 -- SPIRIT IN THE SKY - Gareth Gates & The Kumars 15/03/2003 1 31 52 -- BEING NOBODY - Richard X vs Liberty X 29/03/2003 3 21 ² S/RCA (82876511192) ² Virgin (RXCD1) ä 4 3 -- IGNITION REMIX - R. Kelly 17/05/2003 1 26 53 -- SAY GOODBYE/LOVE AIN'T GONNA WAIT FOR 07/06/2003 2 17 ² Jive (9254972) YOU - S Club Polydor (9807139) 4 -- MAD WORLD - Michael Andrews feat. Gary Jules 27/12/2003 12 2 54 -- NEVER GONNA LEAVE YOUR SIDE - Daniel 02/08/2003 1 16 Adventure/Sanctuary (SANXD250) Bedingfield Polydor (9809364) 5 -- LEAVE RIGHT NOW - Will Young 06/12/2003 12 5 55 -- ROCK YOUR BODY - Justin Timberlake 31/05/2003 2 21 ² S (82876578562) ² Jive (9254952) è 4 6 -- ALL THE THINGS SHE SAID - T.A.T.U. 01/02/2003 1 16 56 -- NO GOOD ADVICE - Girls Aloud 24/05/2003 2 30 ² Interscope (0196972) ² Polydor (9800051) 7 -- CHANGES - Ozzy & Kelly Osbourne 20/12/2003 1 3 57 -- RISE & FALL - Craig David feat. Sting 10/05/2003 2 12 ² Sanctuary (SANXD234) ² Wildstar (CDWILD45) è 4 8 -- BREATHE - Blu Cantrell feat. Sean Paul 09/08/2003 1 18 58 -- HAPPY XMAS (WAR IS OVER) - The Idols 27/12/2003 5 2 Arista (82876545722) S (8287658 3822) è 4 9 -- MAKE LUV - Room 5 feat. -

Edinburgh Feast

The August Feast: A Punter’s Perspective on Edinburgh and its Festivals Brian King The entire book is freely available on the Internet at the following address: http://bkthisandthat.org.uk/ Copyright © Brian King 2005-2015 All rights reserved In Memory of Dick Hixson, whose enthusiastic, intelligent and humorous presence at the Festival breakfast table is much missed. Copyright © Brian King 2005-2015 All rights reserved The August Feast: A Punter’s Perspective on Edinburgh and its Festivals Version dated 7th December 2015 http://bkthisandthat.org.uk/ Contents PREFACE ............................................................................................................................................................................ VI ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ........................................................................................................................................... VIII THE EDINBURGH FEAST ............................................................................................................................................... 9 A PUNTER’S TALE FROM THE FEAST ...................................................................................................................... 11 CHOOSING SHOWS & FEAST MISCELLANY ........................................................................................................ 20 CHOOSING SHOWS ON THE FRINGE ................................................................................................................................ 20 CHOOSING SHOWS FOR OTHER FESTIVALS -

27 March 2020

Mercury Musical Developments and Musical Theatre Network present in partnership with Royal & Derngate, Northampton 26 - 27 March 2020 Shining a light on new British musical theatre mercurymusicals.com musicaltheatrenetwork.com Welcome Theatres like ours exist to bring people together and we were so looking forward to welcoming such an array of musical theatre talent to Northampton this week from across the country and beyond. Sadly that is not possible right now, but we’re determined to continue to champion all the artists who were to perform on our stages this week, so we’ve taken the decision with Mercury Musical Developments and Musical Theatre Network to still publish this year’s BEAM programme, to salary and continue to support all the artists who were due mercurymusicals.com to perform during this week’s showcase and to encourage all who were due to attend to share and distribute their work with one another online. We are so grateful to those of you who were due to be attending this week who have kindly donated the cost of your ticket towards helping us to pay our artists and freelancers. Many of you who attended the UK Musical Theatre Conference here last year will have heard us talk of our commitment to developing new musical theatre for mid-scale regional venues and tours. We’ve had a thrilling year since in which we’ve hosted dozens of artists in Northampton to create original work in partnership with Perfect Pitch, China Plate, Musical Theatre Network, Mercury Musical Developments, Scottish Opera and Improbable. Thanks to the support of an Arts Council England “Ambition For Excellence” grant and partnerships with several midscale venues nationwide, we’re also excited to be able to announce that five of the projects we’ve developed here this year have been fully commissioned. -

1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10Cc I'm Not in Love

Dumb -- 411 Chocolate -- 1975 My Culture -- 1 Giant Leap Dreadlock Holiday -- 10cc I'm Not In Love -- 10cc Simon Says -- 1910 Fruitgum Company The Sound -- 1975 Wiggle It -- 2 In A Room California Love -- 2 Pac feat. Dr Dre Ghetto Gospel -- 2 Pac feat. Elton John So Confused -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Jucxi It Can't Be Right -- 2 Play feat. Raghav & Naila Boss Get Ready For This -- 2 Unlimited Here I Go -- 2 Unlimited Let The Beat Control Your Body -- 2 Unlimited Maximum Overdrive -- 2 Unlimited No Limit -- 2 Unlimited The Real Thing -- 2 Unlimited Tribal Dance -- 2 Unlimited Twilight Zone -- 2 Unlimited Short Short Man -- 20 Fingers feat. Gillette I Want The World -- 2Wo Third3 Baby Cakes -- 3 Of A Kind Don't Trust Me -- 3Oh!3 Starstrukk -- 3Oh!3 ft Katy Perry Take It Easy -- 3SL Touch Me, Tease Me -- 3SL feat. Est'elle 24/7 -- 3T What's Up? -- 4 Non Blondes Take Me Away Into The Night -- 4 Strings Dumb -- 411 On My Knees -- 411 feat. Ghostface Killah The 900 Number -- 45 King Don't You Love Me -- 49ers Amnesia -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Don't Stop -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She Looks So Perfect -- 5 Seconds Of Summer She's Kinda Hot -- 5 Seconds Of Summer Stay Out Of My Life -- 5 Star System Addict -- 5 Star In Da Club -- 50 Cent 21 Questions -- 50 Cent feat. Nate Dogg I'm On Fire -- 5000 Volts In Yer Face -- 808 State A Little Bit More -- 911 Don't Make Me Wait -- 911 More Than A Woman -- 911 Party People.. -

(This Is) a Song for the Lonely

#1 - Nelly #1 Crush - Garbage (take Me Home) Country Roads - Toots And The Maytals (this Is) A Song For The Lonely - Cher (without You) What Do I Do With Me - Tanya Tucker 1 2 Step - Ciara Feat Missy Elliott 1 4 - Feist 1 Thing - Amerie 10,000 Nights - Alphabeat 100 Percent Chance Of Rain - Gary Morris 100 Years - Five For Fighting 1000 Miles - Vanessa Carlton 123 - Gloria Estefan 1-2-3-4 Sumpin' New - Coolio 18 & Life - Skid Row 19 And Crazy - Bomshel 19-2000 - Gorillaz 1973 - James Blunt 1973(radio Version) - James Blunt 1979 - Smashing Pumpkins 1982 - Randy Travis 1985 - Bowling For Soup 1999 - Prince 19th Nervous Breakdown - Rolling Stones 2 Become 1 - Spice Girls, The 2 Faced - Louise 2 Hearts - Kylie Minogue 21 Guns - Green Day 21 Questions - 50 Cent 24 Hours F - Next Of Kin 2-4-6-8 Motorway - Tom Robinson Band 25 Miles - Edwin Starr 25 Or 6 To 4 - Chicago 29 Nights - Danni Leigh 3 Am - Matchbox Twenty 33 (Thirty-Three) - Smashing Pumpkins 4 In The Morning - Gwen Stefani 4 Minutes - Madonna And Justin Timberlake 4 P.m. - Sukiyaki 4 Seasons Of Loneliness - Boyz Ii Men 45 - Shinedown 4ever - Veronicas, The 5 6 7 8 - Steps 5 Colours In Her Hair - Mcfly 50 50 - Lemar 500 Miles - Peter Paul And Mary 500 Miles Away From Home - Bobby Bare 5-4-3-2-1 - Manfred Mann 59th Street Bridge Song - Simon And Garfunkel 6 Soulsville U.s.a - Wilson Pickett 7 - Prince And The New Power Generation 7 Days - Craig David 7 Rooms Of Gloom - Four Tops 7 Ways - Abs 74-75 - Connells 800 Pound Jesus - Sawyer Brown 8th World Wonder - Kimberly Locke 9 To 5 - Dolly -

Download (14MB)

https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ Theses Digitisation: https://www.gla.ac.uk/myglasgow/research/enlighten/theses/digitisation/ This is a digitised version of the original print thesis. Copyright and moral rights for this work are retained by the author A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge This work cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given Enlighten: Theses https://theses.gla.ac.uk/ [email protected] Politics, Pleasures and the Popular Imagination: Aspects of Scottish Political Theatre, 1979-1990. Thomas J. Maguire Thesis sumitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Glasgow University. © Thomas J. Maguire ProQuest Number: 10992141 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest ProQuest 10992141 Published by ProQuest LLC(2018). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States C ode Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC.