Liminal Humans and Other Animals at Skellig Michael

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Birdwatch Ireland Reserves Gannet

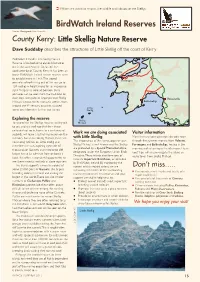

Visitors are asked to respect the wildlife and habitats of the Skelligs BirdWatch Ireland Reserves Gannet. Photograph: Shay Connolly County Kerry: Little Skellig Nature Reserve Dave Suddaby describes the attractions of Little Skellig off the coast of Kerry BirdWatch Ireland’s Little Skellig Nature Reserve is located some eleven kilometres out in the vast Atlantic Ocean off the southwest tip of County Kerry. It has been an Valentia iconic BirdWatch Ireland nature reserve since its establishment in 1969. The jagged Portmagee pinnacles of rock rising out of the sea up to 134 metres in height make for an impressive sight. Despite its isolated position, these pinnacles can be seen from the mainland on clear days, alongside its larger partner, Skellig Waterville Michael, famous for its monastic settlers from Ballinskelligs around the 6 th century onwards, situated Little some one kilometre further out to sea. Skellig Exploring the reserve Skellig To appreciate the Skelligs requires setting out Michael to sea, and it is well worthwhile – these cathedrals of rocks, home to a vast array of seabirds, will leave a lasting impression on the Work we are doing associated Visitor information Many licensed boat operators do daily tours memory. But unlike Skellig Michael, there are with Little Skellig no landing facilities on Little Skellig and The importance of this island, together with through the summer months from Valentia, therefore the awe-inspiring spectacle of Skellig Michael, is well known and the Skelligs Portmagee and Ballinskelligs, leaving in the are protected by a Special Protection Area, thousands of Gannets crammed onto cliff morning and returning in the afternoon. -

The Wild Atlantic Way

The Wild Atlantic Way By IRISH CAR RENTALS Image: Tourism Ireland 1 Contents The Wild Atlantic Way is travelled by thousands of 4 Some of the most popular attractions Irish Car Rentals customers every year. We decided to ask them about their experiences and with that 6 The Search for Skywalker: A Look at Skellig Michael, Co. Kerry information we have compiled a useful guide on the 10 Viewing the Northern Lights: Co. Donegal most frequented and popular places. 12 The Cliffs of Moher: Co. Clare Have you never heard of the Wild Atlantic Way? 16 The Slieve League Coast: Co Donegal Here are a few interesting facts to get you started: 20 Father Ted’s Craggy Island Parochial House: Co. Clare • The Wild Atlantic Way is a 2500km touring 22 Malin Head and Mizen Head: Ireland’s North and South route along the West Coast of Ireland. • It features 157 discovery points, 1000 attractions and more than 2500 activities. • Begins in Kinsale, County Cork and ends at Irelands most northernly point, Malin Head, County Donegal. Image: Fáilte Ireland 2 3 Some of the most popular attractions The Wild Atlantic Way is vast in scope, and choosing what you would most like to see, what order to visit where, or even a place to begin your adventure can seem daunting. That being the case, when we asked our customers which parts they loved in particular, we found several places being mentioned time and again. Cork – Known by its population as and make their journey around the ‘Real Capital of Ireland’, the the Ring a day trip, while others city of Cork is a historic trading port like to sample a little of the time, with a long history. -

As the Majestic Skellig Islands Open to Visitors on April 1, Photographer Sheena Jolley Spent Days on Skellig Michael to Captur

6 fea t u r e WX - V1 As the majestic Skellig islands open to visitors on April 1, photographer Sheena Jolley spent days on Skellig Michael to capture their desolate beauty and thriving wildlife from dawn to dusk, while Áilín Quinlan charts the island’s history PRIL is the cruellest month, according to TS Eliot. But the author of The Waste Land clearly A never got to enjoy Skellig CRAGGY Michael on a clear and sparkling day. The Skelligs are one of the most en- chanting of Ireland’s coastal attractions: pyramids of sandstone which were home to some of the country’s earliest monastic set- tlements and a modern-day sanctuary to a fantastic variety of birdlife. Between April 1 and September, some 11,000 visitors are expected to visit Skellig Michael and climb the 600 hand-carved steps to the monastery atop the 230-metre ISLAND rock. Weekend SATURDAY, MARCH 24, 2007 WX - V1 fea t u r e 7 BIRDS OF A FEATHER: Opposite, nesting pairs of birds on the Skelligs include puffins, guillemot, fulmar, kittiwake, storm petrel, manx shearwater, gannet, herring gull, lesser and greater black backed gulls; above, Sunrise at 5am, the Wailing Widow looks out over small Skellig and the beehivehuts thatwerehome to the early monks. All pictures by Sheena Jolley The island was an important centre of large — probably comprising about 12 guides and other personnel on behalf of to enable dangerous work to be undertak- monastic life for Christian monks who lay-people, 20 monks and an abbot. the Office of Public Works will land on en. -

Tradition and Modernity on Great Blasket Island, Ireland

Tradition and Modernity on Great Blasket Island, Ireland Chris Fennell University of Illinois This interdisciplinary project in archaeology, history, and landscape analysis seeks to examine the lifeways of residents of the Great Blasket Island (Blascaod Mór in the Irish language) off the southwest coast of County Kerry of the Republic of Ireland in the period of 1500 CE through the early 1900s. The lifeways of the residents on the Great Blasket Island were the focus of concerted, nationalist mythology construction by proponents of the new Republic of Ireland in the early 1900s. Those lifeways, supported by maritime and agrarian subsistence, were hailed by nationalist advocates as representing an authentic Irish cultural identity uncorrupted by the impacts of British colonialism, modernity, or new consumer markets. The islanders’ sense of social identities and history likely also embraced perceptions of the prehistoric and medieval features of their cultural landscape. The Blasket Islands are part of the Gaeltacht areas of communities that continue to teach and speak in Gaelic language dialects (Figure 1). Figure 1. Image courtesy Wikimedia commons. 1 Historical Contexts Great Blasket is estimated to have reached a peak population of approximately 170 to 200 people in the early 1900s. The island’s population decreased during the following decades, as emigration to America or to the mainland towns of the new Republic of Ireland drew families away. The few remaining residents departed the island in 1953. New research has begun to examine the cultural landscape and archaeological record of their lifeways from 1500 through the early 1900s (Figures 2, 3) (Coyne 2010; DAHG 2009). -

2019 Exhibition of Photography Tier -1 Not-Accepted Images by Last Name

2019 Exhibition of Photography Tier -1 Not-Accepted Images by Last Name WEN Last Name First Name Division Class and Class Description Title Not-Accepted 3C7D6D Abernathy Mike 1204 Cell Phone 014 - Cell Phone - Color or B & W Valencia, Spain #1 Not Accepted 7DC4E9 Abernathy Mike 1204 Cell Phone 014 - Cell Phone - Color or B & W Valencia, Spain #2 Not Accepted 9240AD Abernathy Mike 1204 Cell Phone 014 - Cell Phone - Color or B & W Cascais, Portugal #1 Not Accepted D696C1 Abernathy Mike 1204 Cell Phone 014 - Cell Phone - Color or B & W Sintra, Portugal Not Accepted A4E1C9 Abeyta Andrea 1207 Color, Black & White or Digital Art 025 - Our Best Friend Khloe Not Accepted 6AA3CB Abulafia Lewis 1205 Black & White 015 - Scenic - landscapes, waterscapes Icelandic Coast Not Accepted 98A368 Abulafia Lewis 1201 Color Scenic - Landscape 003 - Fall Alaskan Sunrise Not Accepted B97922 Abulafia Lewis 1201 Color Scenic - Landscape 004 - Winter Iceberg #1 Not Accepted CBB63C Abulafia Lewis 1203 Color Nature 012 - Wild Animals - Birds Puffins #1 Not Accepted EED1B1 Abulafia Lewis 1201 Color Scenic - Landscape 004 - Winter Icelandic Icebergs Not Accepted 5025B0 Acevedo Carmen 1204 Cell Phone 014 - Cell Phone - Color or B & W Shapes Within Not Accepted 28540D Adams Donald 1207 Color, Black & White or Digital Art 026 - Family Moments Still have to concentrate Not Accepted 444E47 Adams Donald 1209 Digital Art 032 - Digital Photographic Art Mythical Place Not Accepted 89F02E Adams Donald 1201 Color Scenic - Landscape 003 - Fall Enjoying the simple things Not Accepted -

Embrace the Wild Atlantic Way of Life

SOUTHERN PENINSULAS & HAVEN COAST WildAtlanticWay.com #WildAtlanticWay WELCOME TO THE SOUTHERN PENINSULAS & HAVEN COAST The Wild Atlantic Way, the longest defined coastal touring route in the world stretching 2,500km from Inishowen in Donegal to Kinsale in West Cork, leads you through one of the world’s most dramatic landscapes. A frontier on the very edge of Europe, the Wild Atlantic Way is a place like no other, which in turn has given its people a unique outlook on life. Here you can immerse yourself in a different way of living. Here you can let your freer, spontaneous side breathe. Here you can embrace the Wild Atlantic Way of Life. The most memorable holidays always have a touch of wildness about them, and the Wild Atlantic Way will not disappoint. With opportunities to view the raw, rugged beauty of the highest sea cliffs in Europe; experience Northern Lights dancing in winter skies; journey by boat to many of the wonderful islands off our island; experience the coast on horseback; or take a splash and enjoy the many watersports available. Stop often at the many small villages and towns along the route. Every few miles there are places to stretch your legs and have a bite to eat, so be sure to allow enough time take it all in. For the foodies, you can indulge in some seaweed foraging with a local guide with a culinary experience so you can taste the fruits of your labours. As night falls enjoy the craic at traditional music sessions and even try a few steps of an Irish jig! It’s out on these western extremities – drawn in by the constant rhythm of the ocean’s roar and the consistent warmth of the people – that you’ll find the Ireland you have always imagined. -

Skellig Michael

History Geology Getting there The word Sceillic means a rock, particularly a steep rock. The The pinnacles of the Skellig Islands (Great Skellig, also known Skellig Michael is 11.6 km from first reference to Skellig occurs in legend when it is given as the as Skellig Michael and Little Skellig), which rise 218m above the the mainland and is accessible Co. Kerry burial place of Ir, son of Milesius, who was drowned during the ocean, are formed from the durable Old Red Sandstone that by boat between the months Skellig Michael, landing of the Milesians. A fifth century reference describes the also forms the backbone of the mountainous regions of South of May and September, flight of Duagh, King of West Munster, to the Skelligs. We have West Kerry and West Cork. These rocks began life as sediments subject to weather conditions. no means of knowing whether a monastery existed on the site deposited in the Devonian period some 400 million years ago. Boats carrying passengers to at that time. These rocks were subsequently altered in a period of folding Skellig Michael operate from World Heritage Site ViSitor’S Guide and mountain building some 100 million years later. Sea level Knightstown, Portmagee, A monastery may have been founded as early as the 6th century subsequently rose, forming the deep marine inlets of south- Ballinskelligs and Caherdaniel. but the first reference to monks on the Skelligs dates to the 8th western Ireland and isolating the Skelligs from the mainland. During the tourist season there century when the death of ‘Suibhni of Scelig’ is recorded. -

The Living Tradition of Saints in the British Isles 10 Ireland: Monks And

The Living Tradition of Saints in the British Isles 10 Ireland: Monks and Islands Community of St Bega, St Mungo and St Herbert Fr John Musther, 16 Greta Villas, KESWICK, Cumbria CA12 5LJ www.orthodoxcumbria.org St Enda's Church ,Inishmore, Aran 2 Historians argue as to whether St Patrick ever founded a monastery. In his own words, 'The sons of the Irish and the daughters of their kings are monks and brides of Christ’. This may apply to individuals, not monasteries. But without question monasteries sprang up in abundance in a very short time - the 6C was the apogee of monastic growth. Everywhere the local tribe gave land for them to enclose and build a church. St Enda may have built a monastery on Inishmore in the Aran islands Co Galway in 480. He lived there for 50 years. Killeany ('church of Enda') is the site of St Enda's monastery. Another more beautiful spot can scarcely be found. It looks across the sea to Connemara with its 12 'bens', or mountains. The place made a huge impression on me, so much so that I once had a vivid dream that the Last Day began here and all the dead were being raised from their graves. As I watched the dead come forth with nanosecond speed, all I could hear was a heavenly choir singing 'And the dead shall be raised...' over and over again. It was frighteningly real, and utterly scary. Since then I have revered this mound of sand as truly sacred ground. It is not surprising: St Enda and 120 of his brethren are said to lie under it. -

A Letter from Ireland: Volume 2

A Letter from Ireland: Volume 2 Mike Collins lives in County Cork, Ireland. He travels around the island of Ireland with his wife, Carina, taking pictures and listening to stories about families, names and places. He and Carina share these pictures and stories at: www.YourIrishHeritage.com He also writes a weekly Letter from Ireland, which is sent out to people of Irish ancestry all over the world. This volume is the second collection of those letters. A Letter from Ireland: Volume 2 Irish Surnames, Counties, Culture and Travel Mike Collins Your Irish Heritage. First published 2014 by Your Irish Heritage Email: [email protected] Website: www.youririshheritage.com © Mike Collins 2014 All Rights Reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or utilised in any form or any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or in any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the author. All quotations have been reproduced with original spelling and punctuation. All errors are the author’s own. CREDITS All photographs and illustrative materials are the author’s own. The publisher gratefully acknowledges the many individuals who granted A Letter from Ireland permission to reprint the cited material. ISBN: DESIGN Cover design by Ian Armstrong, Onevision Media Your Irish Heritage, Old Abbey, Cork, Ireland PRAISE FOR ‘A LETTER FROM IRELAND’ It's a great book for those, like myself, who have read a great deal about the history in which my ancestors live but still scratch their heads feeling like there's something missing. Mike fills in many of those gaps in interesting and thought provoking ways, making you crave more. -

Ring of Kerry Itinerary

Ring of Kerry Itinerary THE RING OF KERRY DRIVE We've driven the Ring of Kerry a few times now and it never gets old. I may not say that in a few years when every single person who visits us in Ireland wants to do a Ring of Kerry road trip but for now, let's say visiting the Ring of Kerry is an Irish rite of passage. From Donegal, it is quite a drive and it takes us around 6 hours but we decided upon a few other stops on our road trip. We drive right through Sligo which is one of Ireland's most underappreciated counties and it is spectacular. From Yeats grave to the beautiful surfing beaches Sligo is sensational. From Sligo, we headed straight to Galway City where we stayed a couple of days to enjoy the craic and the crowds. Then from Galway, we went onto to Tralee which is where we began our Ring of Kerry epic adventure. We stopped in Tralee for some epic fish and chips at Quinlan's Seafood Bar absolutely bloody spectacular food so fresh it was practically still flapping. At Quinlan's, we also heard for the very first time a true Kerry accent which is quite a thick Irish one. The slang used in Kerry is also different than the rest of Ireland so if someone calls you a "lad" and your female that's the Kerry way. By the way, the blue highlighted text is a link so you can click on it and it will open an article on that area. -

The Far Side of the Sky

The Far Side of the Sky Christopher E. Brennen Pasadena, California Dankat Publishing Company Copyright c 2014 Christopher E. Brennen All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, transmitted, transcribed, stored in a retrieval system, or translated into any language or computer language, in any form or by any means, without prior written permission from Christopher Earls Brennen. ISBN-0-9667409-1-2 Preface In this collection of stories, I have recorded some of my adventures on the mountains of the world. I make no pretense to being anything other than an average hiker for, as the first stories tell, I came to enjoy the mountains quite late in life. But, like thousands before me, I was drawn increasingly toward the wilderness, partly because of the physical challenge at a time when all I had left was a native courage (some might say foolhardiness), and partly because of a desire to find the limits of my own frailty. As these stories tell, I think I found several such limits; there are some I am proud of and some I am not. Of course, there was also the grandeur and magnificence of the mountains. There is nothing quite to compare with the feeling that envelopes you when, after toiling for many hours looking at rock and dirt a few feet away, the world suddenly opens up and one can see for hundreds of miles in all directions. If I were a religious man, I would feel spirits in the wind, the waterfalls, the trees and the rock. Many of these adventures would not have been possible without the mar- velous companionship that I enjoyed along the way. -

Beehives on the Border of Humanity: the Monks of Skellig Michael

Beehives on the Border of Humanity: The Monks of Skellig Michael Dr. Corey Wrenn Lecturer in Sociology, University of Kent Chair, Animals & Society Section of the American Sociological Association Highlights •Premodern Ireland offers a construction human/animal boundary-making and resistance •The Skellig Michael experiment intentionally challenged the humanity project Making Sense of PreModern Human- Nonhuman Relations • Marx and historical materialism • Inequalities and the ideologies that maintain them emerge from economy • Speciesism emerges with sexism under hunting, evolves with classism under agricultural & feudal systems (Nibert 2002) • Critical animal studies and the construction of human and animal as symbolic categories • “Civilization” project defined human characteristics as distinct from other animals • Colonization key to process (Ko 2019) Medieval Ireland • Not reached by Roman colonizers • But Christianity took hold by the 400s • Colonized by Vikings, Normans, and later British • Irish Church marched to the beat of its own drum • On the outskirts of Christendom • Blend of indigenous Gaelic paganism and Roman Catholicism Medieval Ireland • Pre-Christian Ireland was cattle economy • Shift from Celticism to Christianity included shift from species semi-egalitarianism to anthropocentrism • Uneven process… • Ireland itself on the boundary of known world / Christendom Skellig Michael • Founded between 6th and 8th c. • Off Co Kerry • National bird reserve • UNESCO Site Why the Skellig? • Isolated, difficult to reach • On the border