Process for the Extracting Oxygen and Iron from Iron Oxide-Containing Ores

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Iron (III) Oxide Anhydrous

Material Safety Data Sheet Iron (III) Oxide Anhydrous MSDS# 11521 Section 1 - Chemical Product and Company Identification MSDS Name: Iron (III) Oxide Anhydrous Catalog Numbers: I116-3, I116-500 Synonyms: Ferric Oxide Red; Iron (III) Oxide; Iron Sesquioxide; Red Iron Oxide. Fisher Scientific Company Identification: One Reagent Lane Fair Lawn, NJ 07410 For information in the US, call: 201-796-7100 Emergency Number US: 201-796-7100 CHEMTREC Phone Number, US: 800-424-9300 Section 2 - Composition, Information on Ingredients ---------------------------------------- CAS#: 1309-37-1 Chemical Name: Iron (III) Oxide %: 100 EINECS#: 215-168-2 ---------------------------------------- Hazard Symbols: None listed Risk Phrases: None listed Section 3 - Hazards Identification EMERGENCY OVERVIEW Warning! May cause respiratory tract irritation. May cause mechanical eye and skin irritation. Inhalation of fumes may cause metal-fume fever. Causes severe digestive tract irritation with pain, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea. May corrode the digestive tract with hemorrhaging and possible shock. Target Organs: None. Potential Health Effects Eye: Dust may cause mechanical irritation. Skin: Dust may cause mechanical irritation. May cause severe and permanent damage to the digestive tract. May cause liver damage. Causes severe pain, Ingestion: nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and shock. May cause hemorrhaging of the digestive tract. The toxicological properties of this substance have not been fully investigated. Dust is irritating to the respiratory tract. Inhalation of fumes may cause metal fume fever, which is characterized Inhalation: by flu-like symptoms with metallic taste, fever, chills, cough, weakness, chest pain, muscle pain and increased white blood cell count. Chronic: Chronic inhalation may cause effects similar to those of acute inhalation. -

Fortificants

GFF5.qxd 14/11/06 16:44 Page 93 PA RT I I I Fortificants: physical characteristics, selection and use with specific food vehicles GFF5.qxd 14/11/06 16:44 Page 94 GFF5.qxd 14/11/06 16:44 Page 95 Introduction By providing a critical review of the fortificants that are currently available for fortification purposes, Part III of these guidelines is intended to assist pro- gramme managers in their choice of firstly, a suitable food vehicle and secondly, a compatible fortificant. Having established – through the application of appro- priate criteria – that the nature of the public health risk posed by a micronutri- ent deficiency justifies intervention in the form of food fortification, the selection of a suitable combination of food vehicle and fortificant(s), or more specifically, the chemical form of the micronutrient(s) that will added to the chosen food vehicle, is fundamental to any food fortification programme. Subsequent chap- ters (Part IV) cover other important aspects of food fortification programme planning, including how to calculate how much fortificant to add to the chosen food vehicle in order to achieve a predetermined public health benefit (Chapter 7), monitoring and impact evaluation (Chapters 8 and 9), marketing (Chapter 10) and regulatory issues (Chapter 11). In practice, the selection of a food vehicle–fortificant combination is governed by range of factors, both technological and regulatory. Foods such as cereals, oils, dairy products, beverages and various condiments such as salt, sauces (e.g. soy sauce) and sugar are particularly well suited to mandatory mass fortifica- tion. These foods share some or all of the following characteristics: • They are consumed by a large proportion of the population, including (or especially) the population groups at greatest risk of deficiency. -

Depositional Setting of Algoma-Type Banded Iron Formation Blandine Gourcerol, P Thurston, D Kontak, O Côté-Mantha, J Biczok

Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation Blandine Gourcerol, P Thurston, D Kontak, O Côté-Mantha, J Biczok To cite this version: Blandine Gourcerol, P Thurston, D Kontak, O Côté-Mantha, J Biczok. Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation. Precambrian Research, Elsevier, 2016. hal-02283951 HAL Id: hal-02283951 https://hal-brgm.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-02283951 Submitted on 11 Sep 2019 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Accepted Manuscript Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation B. Gourcerol, P.C. Thurston, D.J. Kontak, O. Côté-Mantha, J. Biczok PII: S0301-9268(16)30108-5 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres.2016.04.019 Reference: PRECAM 4501 To appear in: Precambrian Research Received Date: 26 September 2015 Revised Date: 21 January 2016 Accepted Date: 30 April 2016 Please cite this article as: B. Gourcerol, P.C. Thurston, D.J. Kontak, O. Côté-Mantha, J. Biczok, Depositional Setting of Algoma-type Banded Iron Formation, Precambrian Research (2016), doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.precamres. 2016.04.019 This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. -

Earth Systems Science Grades 9-12

Earth Systems Science Grades 9-12 Lesson 2: The Irony of Rust The Earth can be considered a family of four major components; a biosphere, atmosphere, hydrosphere, and geosphere. Together, these interacting and all-encompassing subdivisions constitute the structure and dynamics of the entire Earth. These systems do not, and can not, stand alone. This Module demonstrates, at every grade level, the concept that one system depends on every other for molding the Earth into the world we know. For example, the biosphere could not effi ciently prosper as is without gas exchange from the atmosphere, liquid water from the hydrosphere, and food and other materials provided by the geosphere. Similarly, the other systems are signifi cantly affected by the biosphere in one way or another. This Module uses Earth’s systems to provide the ultimate lesson in teamwork. March 2006 2 JOURNEY THROUGH THE UNIVERSE Lesson 2: The Irony of Rust Lesson at a Glance Lesson Overview In this lesson, students will investigate the chemistry of rust—the forma- tion of iron oxide (Fe2O3)—within a modern context, by experimenting with the conditions under which iron oxide forms. Students will apply what they have learned to deduce the atmospheric chemistry at the time that the sediments, which eventually became common iron ore found in the United States and elsewhere, were deposited. Students will interpret the necessary formation conditions of this iron-bearing rock in the context of Earth’s geochemical history and the history of life on Earth. Lesson Duration Four 45-minute class periods plus 10 minutes a day for maintence and observation for two weeks Core Education Standards National Science Education Standards Standard B3: A large number of important reactions involve the transfer of either electrons (oxidation/reduction reactions) or hydrogen ions (acid/base reactions) between reacting ions, molecules, or atoms. -

Unique Properties of Water!

Name: _______ANSWER KEY_______________ Class: _____ Date: _______________ Unique Properties of Water! Word Bank: Adhesion Evaporation Polar Surface tension Cohesion Freezing Positive Universal solvent Condensation Melting Sublimation Dissolve Negative 1. The electrons are not shared equally between the hydrogen and oxygen atoms of water creating a Polar molecule. 2. The polarity of water allows it to dissolve most substances. Because of this it is referred to as the universal solvent 3. Water molecules stick to other water molecules. This property is called cohesion. 4. Hydrogen bonds form between adjacent water molecules because the positive charged hydrogen end of one water molecule attracts the negative charged oxygen end of another water molecule. 5. Water molecules stick to other materials due to its polar nature. This property is called adhesion. 6. Hydrogen bonds hold water molecules closely together which causes water to have high surface tension. This is why water tends to clump together to form drops rather than spread out into a thin film. 7. Condensation is when water changes from a gas to a liquid. 8. Sublimation is when water changes from a solid directly to a gas. 9. Freezing is when water changes from a liquid to a solid. 10. Melting is when water changes from a solid to a liquid. 11. Evaporation is when water changes from a liquid to a gas. 12. Why does ice float? Water expands as it freezes, so it is LESS DENSE AS A SOLID. 13. What property refers to water molecules resembling magnets? How are these alike? Polar bonds create positive and negative ends of the molecule. -

Standard Reference Materials Price and Availability List IMPORTANT NOTICE to PURCHASERS and USERS of NBS STANDARD REFERENCE MATERIALS

o A UNITED STATES NBS SPECIAL PUBLICATION DEPARTMENTucrnn 1 ivitii 1 urOF COMMERCE PUBLICATION 260 [ A SUPPLEMENT JANUARY, 1972 Standard Reference Materials Price and Availability List IMPORTANT NOTICE TO PURCHASERS AND USERS OF NBS STANDARD REFERENCE MATERIALS The Office of Standard Reference Materials no longer issues the Quarterly Insert Sheets to update the current issue of the SRM Catalog. Instead a Standard Reference Material Availability and Price List is issued semiannually. The format has been changed to improve readability and the List is organized as follows: Section I - A list of all classes of materials currently available arranged by Standard Reference Material (SRM), Research Material (RM), and General Material (GM) numbers, together with type, unit of issue, and current price. Section Ila — A list of all classes of materials that have been issued since the Catalog (July 1970) was published, arranged by SRM, RM, and GM numbers together with catalog category. Section lib — A short description, arranged by catalog category, of all SRM's issued since the Catalog (July 1970) was published and therefore not contained therein. For ease of reproduction, tables have been condensed and are, in general, not in the same format used in the catalog. (Please note that the values shown are nominal values. The actual values certified are given on the Certificate which accompanies the material.) The unit of issue and price are given after the description of each SRM. Section llla — A list, arranged by SRM numbers, of recently issued certificates (final or revised versions). Section Illb — A list, arranged by SRM, RM, and GM numbers, of all items that have gone out of stock since the effective date of the current catalog. -

Banded Iron Formations

Banded Iron Formations Cover Slide 1 What are Banded Iron Formations (BIFs)? • Large sedimentary structures Kalmina gorge banded iron (Gypsy Denise 2013, Creative Commons) BIFs were deposited in shallow marine troughs or basins. Deposits are tens of km long, several km wide and 150 – 600 m thick. Photo is of Kalmina gorge in the Pilbara (Karijini National Park, Hamersley Ranges) 2 What are Banded Iron Formations (BIFs)? • Large sedimentary structures • Bands of iron rich and iron poor rock Iron rich bands: hematite (Fe2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), siderite (FeCO3) or pyrite (FeS2). Iron poor bands: chert (fine‐grained quartz) and low iron oxide levels Rock sample from a BIF (Woudloper 2009, Creative Commons 1.0) Iron rich bands are composed of hematitie (Fe2O3), magnetite (Fe3O4), siderite (FeCO3) or pyrite (FeS2). The iron poor bands contain chert (fine‐grained quartz) with lesser amounts of iron oxide. 3 What are Banded Iron Formations (BIFs)? • Large sedimentary structures • Bands of iron rich and iron poor rock • Archaean and Proterozoic in age BIF formation through time (KG Budge 2020, public domain) BIFs were deposited for 2 billion years during the Archaean and Proterozoic. There was another short time of deposition during a Snowball Earth event. 4 Why are BIFs important? • Iron ore exports are Australia’s top earner, worth $61 billion in 2017‐2018 • Iron ore comes from enriched BIF deposits Rio Tinto iron ore shiploader in the Pilbara (C Hargrave, CSIRO Science Image) Australia is consistently the leading iron ore exporter in the world. We have large deposits where the iron‐poor chert bands have been leached away, leaving 40%‐60% iron. -

Electrolytic Iron

ELECTROLYTIC IRON ; DEPOSITED BY T H E COMMI T T E E O N (Brafcmate StuMes. 1 x ACC. No DATE ELECTROLYTIC IRON.. A STUDY OF THE PRODUCTION OF IRON BY ELECTROLYSIS, WITH SPECIAL REFERENCE TO ITS RECOVERY FROM SULPHIDE ORES.. THESIS Submitted by WILLIAM RAYMOND MoCLELLAND As Part of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Soienoe. MAY L925. MoOILL UNIVERSITY, MONTREAL, CANADA. ELECTROLYTIC IRON. A Study of the Production of Iron by Electrolysis, with Special: Reference to its Recovery from Sulphide Ores.- PART I. Introduction Historical Outline and Descriptive* Physical Properties of Electrolytic Iron. PART II Theoretioal Considerations. A. Leaohing. B. Electrolysis. PART III. Experimental Research. A. Ore Body and Treatment of Ore. B. Leaching. C. Electro-deposition. General Summary and Conclusion. PART IV. Appendix. References. Sample Calculations. Bibliography. (1) PART I. INTRODUCTION. Iron, is the oommonest, most widely used, and at the same time the most vitally important of all the base metals. In the growth and developementr of modern civilization it assumes a dominant position.. Iron was not unknown to the anoients,nor were they unaware of its uses. As early as 1500 B.C.. the inhabitants of India; fashioned swords and spear heads. They even recognized, its qualities: for purpose* of construotion. Wrought1: iron beams measuring twenty feet in length have been found in the temple of Kanaruk dating from 1250 B.C. The metallurgy of iron at this period was extremely primative and continued so for many hundreds of year.s. It v;as notr until the sixteenth century that the introduction of-the air blast into the furnaoff made the progress of iron manufacture comparatively rapid.From thi'a period on, tha production increase-d. -

The Preparation of High-Purity Iron (99.987%) Employing a Process of Direct Reduction–Melting Separation–Slag Refining

materials Article The Preparation of High-Purity Iron (99.987%) Employing a Process of Direct Reduction–Melting Separation–Slag Refining Bin Li 1,2, Guanyong Sun 1,2, Shaoying Li 1,2, Hanjie Guo 1,2,* and Jing Guo 1,2 1 School of Metallurgical and Ecological Engineering, University of Science and Technology Beijing, Beijing 100083, China; [email protected] (B.L.); [email protected] (G.S.); [email protected] (S.L.); [email protected] (J.G.) 2 Beijing Key Laboratory of Special Melting and Preparation of High-End Metal Materials, Beijing 100083, China * Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel.: +86-138-0136-9943 Received: 9 March 2020; Accepted: 9 April 2020; Published: 14 April 2020 Abstract: In this study, high-purity iron with purity of 99.987 wt.% was prepared employing a process of direct reduction–melting separation–slag refining. The iron ore after pelletizing and roasting was reduced by hydrogen to obtain direct reduced iron (DRI). Carbon and sulfur were removed in this step and other impurities such as silicon, manganese, titanium and aluminum were excluded from metallic iron. Dephosphorization was implemented simultaneously during the melting separation step by making use of the ferrous oxide (FeO) contained in DRI. The problem of deoxidization for pure iron was solved, and the oxygen content of pure iron was reduced to 10 ppm by refining with a high basicity slag. Compared with electrolytic iron, the pure iron prepared by this method has tremendous advantages in cost and scale and has more outstanding quality than technically pure iron, making it possible to produce high-purity iron in a short-flow, large-scale, low-cost and environmentally friendly way. -

Combustion of Iron Wool – Student Sheet

Combustion of iron wool – Student sheet To study Iron is a metal. Iron wool is made up of thin strands of iron loosely bundled together. Your teacher has attached a piece of iron wool to a see-saw balance. At the other end of the see-saw is a piece of Plasticine. Iron wool can combust. Your teacher is going to make the iron wool combust by heating it. If there is a change in mass, the see-saw will either tip to the left or to the right. To discuss or to answer 1 What do you think will happen? ............................................................................................................................................................. 2 Why do you think this will happen? ............................................................................................................................................................. ............................................................................................................................................................. 3 What do you see happen when it is demonstrated? ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 Was your prediction correct? ............................................................................................................................................................. Nuffield Practical Work for Learning: Model-based Inquiry • Combustion of iron wool • Student sheets page 1 of 4 © Nuffield Foundation 2013 • downloaded from -

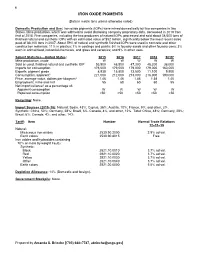

Iron Oxide Pigments Data Sheet

90 IRON OXIDE PIGMENTS (Data in metric tons unless otherwise noted) Domestic Production and Use: Iron oxide pigments (IOPs) were mined domestically by two companies in two States. Mine production, which was withheld to avoid disclosing company proprietary data, decreased in 2019 from that of 2018. Five companies, including the two producers of natural IOPs, processed and sold about 38,000 tons of finished natural and synthetic IOPs with an estimated value of $52 million, significantly below the most recent sales peak of 88,100 tons in 2007. About 59% of natural and synthetic finished IOPs were used in concrete and other construction materials; 11% in plastics; 7% in coatings and paints; 5% in foundry sands and other foundry uses; 3% each in animal food, industrial chemicals, and glass and ceramics; and 9% in other uses. Salient Statistics—United States: 2015 2016 2017 2018 2019e Mine production, crude W W W W W Sold or used, finished natural and synthetic IOP 53,500 48,500 47,300 48,200 38,000 Imports for consumption 176,000 179,000 179,000 179,000 160,000 Exports, pigment grade 8,930 15,800 13,500 11,100 9,900 Consumption, apparent1 221,000 212,000 213,000 216,000 190,000 Price, average value, dollars per kilogram2 1.46 1.46 1.46 1.58 1.40 Employment, mine and mill 55 60 60 60 55 Net import reliance3 as a percentage of: Apparent consumption W W W W W Reported consumption >50 >50 >50 >50 >50 Recycling: None. Import Sources (2015–18): Natural: Spain, 43%; Cyprus, 36%; Austria, 10%; France, 9%; and other, 2%. -

05/2203 Iron Oxide Extraction from Lunar and Martian Regoliths

05/2203 Iron oxide extraction from lunar and Martian regoliths Type of activity: Medium Study (4 months, 25 KEUR) Background The Reformer iron Sponge Cycle (RESC) has been proposed as a valid process to produce highly pure hydrogen from virtually any kind of hydrocarbon fuel on a bed of iron oxide (magnetite Fe3O4), present in the soils of the Moon and Mars. The process has been investigated in the frame of the Ariadna Call for Proposals 04/01 in view of future long-term manned lunar and Martian exploration. The process permits to operate a hydrogen-oxygen fuel cell for electrical power generation by producing hydrogen from either high energy density fuels brought from Earth or from fuels produced in situ (e.g. methane from the Sabatier process of from biomass decomposition). Fuels are converted into a mixture of hydrogen and carbon monoxide in a reforming reactor. In the following Iron Sponge Cycle iron oxide (magnetite/wuestite) is initially reduced by hydrogen and carbon monoxide to a lower oxide or down to iron metal with production of water steam and carbon dioxide. In a second step water steam is passed on the formed iron metal bed; iron oxide is replenished and water steam is reduced to highly pure hydrogen which can be fed without further purification treatments to the anodic compartment of a fuel cell for electrical power generation. The contact mass (iron/iron oxide) properties as size, porosity and composition of the pellets are very critical. The use of pure iron would theoretically maximise the efficiency of the cycle; the lifetime of the pellets is however limited by sintering effects.