An Interview with Scott Eyre1 About Playing Major

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

November, 2006

By the Numbers Volume 16, Number 4 The Newsletter of the SABR Statistical Analysis Committee November, 2006 Review Academic Research: Errors and Official Scorers Charlie Pavitt The author describes a recent academic study investigating the change in error rates over time, and speculating on the role of the official scorer in the “home field advantage” for errors. This is one of a series of reviews of sabermetric articles published in academic journals. It is part of a project of mine to collect and catalog sabermetric research, and I would appreciate learning of and receiving copies of any studies of which I am unaware. Please visit the Statistical Baseball Research Bibliography at www.udel.edu/communication/pavitt/biblioexplan.htm . Use it for your research, and let me know what is missing. per game, used as a proxy for team speed, were positively related David E. Kalist and Stephen J. Spurr, Baseball with errors; others have previously noticed the speed/error Errors, Journal of Quantitative Analysis in association. Sports, Volume 2, Issue 4, Article 3 Interestingly, the National League has consistently “boasted” more errors than the American League; the authors are unsure In its short existence, JQAS has shown a tendency to present why, but comparisons both before and after the appearance of the articles that are long on method but short on interesting designated hitter in the junior circuit indicate that this is probably substance (case in point, another piece in Volume 2 Issue 4 not the reason. relevant to the tired old topic of within-league parity). Kalist and Spurr’s effort is a welcome change. -

Sell It Fast with Ukiah Daily Journal Classifieds

Community Your health: FORUM sports digest Ask Dr. Gott Why Measure V? .............Page 6 ..............Page 3 ...................................Page 4 INSIDE Mendocino County’s World briefly The Ukiah local newspaper ..........Page 2 Tomorrow: Sunny and very warm 7 58551 69301 0 TUESDAY May 16, 2006 50 cents tax included DAILY JOURNAL ukiahdailyjournal.com 16 pages, Volume 148 Number 37 email: [email protected] City looks for Death on Highway 20 ways to curb sewer bills The Daily Journal The Ukiah City council this week will be looking at how it might give seniors and low-income resi- dents a break on the new higher sewer and water fees that went into effect in December. Because state law prohibits the city from reducing rates for one sector of the public by increasing rates to, say, larger users, the city is trying to find inven- tive ways to help seniors and low income residents. Among the things they’ll look at: • Using General Fund monies to subsidize the cost to these seniors and low-income residents. However, it’s unknown how that would impact the city’s bud- get. See AGENDA, Page 14 Votes in on winegrape commission By BEN BROWN The Daily Journal The polls have closed on the vote to approve or deny the Mendocino Wine and Winegrape Isaac Eckel/The Daily Journal Commission and the required 40 percent of ballots The remains of a Toyota truck and debris line Route 20 after it collided with a semi truck Monday, killing the driver of from grape growers and wine makers have been col- the Toyota and closing the road in both directions. -

Memorial Day Memorial

Memorial Day -Weekend Sale- MAY 22–25 Biannual www.frontier-justice.com Sale While supplies last Personal Safety for You and Your Family $649.99 Sale Price $699.99 2 FOR $99.99 $379.99 Reg. Price $749.99 Reg. Price $59.99/each Reg. Price $449.99 $449.99 Must purchase two for sale price. HK VP9, OPTIC READY, SMITH & WESSON M&P Reg. Price $519.99 9mm ANDERSON, AM-15, SHIELD 2.0, 9mm, NTS CZ P-10F, 9mm ITEM 81000483 STRIPPED LOWER ITEM 11808 Also available in FDE RECEIVER ITEM 91540 FREE Sale Price $14.99 Reg. Price $24.99 $209.99 FREE with purchase of FREE Glock 17, 19, 26, 34, 45 Reg. Price $249.99 $39.99 Sale Price $17.99 for members only Reg. Price $29.99 GSG FIREFLY, .22LR, ETS, 9mm GLOCK Reg. Price $64.99 FREE with purchase of THREADED BARREL, BLK MAG, 31RD WALKER’S RAZOR SLIM handgun for members only ITEM GERG2210TFF ITEM GLK-18 ELECTRONIC EAR MUFFS, MULTICAM SNAPSAFE LARGE Also available in FDE LOCKBOX, KEYED ITEM 75200 ITEM GWP-RSEM-MCC $65 Basic Pistol Class Save $10 (Reg. $75) $10.99 Plus, get a FREE GIFT Sale Price $12.99 When you purchase this class. Valued at $60. $89.99 Reg. Price $14.99 Reg. Price $99.99 FREE GIFT $60 Value: AMMO INC Pistol Cleaning Kit $9.99 AMMO INC .223 SIGNATURE SERIES Ear Protection $15.99 55GR FMJ 200RD 9mm 115GR 50RD Eye Protection $3.99 Range Pass $29 ITEM 223055FMJ-RB200 ITEM 9115TMC-A50 EMS Week We are Mission Ready Purchase a raffle ticket during the sale for a chance to win a gun concealment wall art piece (as pictured below) and an Annual Individual Membership at Frontier Justice! All proceeds from the raffle tickets benefit Life Star of Kansas City. -

BASE 1 Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® 2

BASE 1 Miguel Cabrera Detroit Tigers® 2 Michael Brantley Cleveland Indians® 3 Yasmani Grandal Los Angeles Dodgers® 4 Byron Buxton Minnesota Twins® RC 5 Daniel Murphy New York Mets® 6 Clay Buchholz Boston Red Sox® 7 James Loney Tampa Bay Rays™ 8 Dee Gordon Miami Marlins® 9 Khris Davis Milwaukee Brewers™ 10 Trevor Rosenthal St. Louis Cardinals® 11 Jered Weaver Angels® 12 Lucas Duda New York Mets® 13 James Shields San Diego Padres™ 14 Jacob Lindgren New York Yankees® RC 15 Michael Bourn Cleveland Indians® 16 Yunel Escobar Washington Nationals® 17 George Springer Houston Astros® 18 Ryan Howard Philadelphia Phillies® 19 Justin Upton San Diego Padres™ 20 Zach Britton Baltimore Orioles® 21 Santiago Casilla San Francisco Giants® 22 Max Scherzer Washington Nationals® 23 Carlos Carrasco Cleveland Indians® 24 Angel Pagan San Francisco Giants® 25 Wade Miley Boston Red Sox® 26 Ryan Braun Milwaukee Brewers™ 27 Carlos Gonzalez Colorado Rockies™ 28 Chase Utley Philadelphia Phillies® 29 Brandon Moss Cleveland Indians® 30 Juan Lagares New York Mets® 31 David Robertson Chicago White Sox® 32 Carlos Santana Cleveland Indians® 33 Ender Inciarte Arizona Diamondbacks® 34 Jimmy Rollins Los Angeles Dodgers® 35 J.D. Martinez Detroit Tigers® 36 Yadier Molina St. Louis Cardinals® 37 Ryan Zimmerman Washington Nationals® 38 Stephen Strasburg Washington Nationals® 39 Torii Hunter Minnesota Twins® 40 Anibal Sanchez Detroit Tigers® 41 Michael Cuddyer New York Mets® 42 Jorge De La Rosa Colorado Rockies™ 43 Shane Greene Detroit Tigers® 44 John Lackey St. Louis Cardinals® 45 Hyun-Jin Ryu Los Angeles Dodgers® 46 Lance Lynn St. Louis Cardinals® 47 David Freese Angels® 48 Russell Martin Toronto Blue Jays® 49 Jose Iglesias Detroit Tigers® 50 Pablo Sandoval Boston Red Sox® 51 Will Middlebrooks San Diego Padres™ 52 Joe Mauer Minnesota Twins® 53 Chris Archer Tampa Bay Rays™ 54 Starling Marte Pittsburgh Pirates® 55 Jason Heyward St. -

Vs PHILADELPHIA PHILLIES (11-7) Friday, April 20, 2018 – Citizens Bank Park – 7:05 EDT – Game 19; Home 8 RHP Ivan Nova (2-1, 4.88) Vs RHP Ben Lively (0-1, 5.87)

PITTSBURGH PIRATES (12-7) vs PHILADELPHIA PHILLIES (11-7) Friday, April 20, 2018 – Citizens Bank Park – 7:05 EDT – Game 19; Home 8 RHP Ivan Nova (2-1, 4.88) vs RHP Ben Lively (0-1, 5.87) LAST NIGHT’S ACTION: The Phillies defeated the Pittsburgh Pirates, 7-0, at Citizens Bank Park … Starter Jake Arrieta (W, 2-0) tossed 7.0 scoreless innings and allowed a single hit with 10 PHILLIES PHACTS strikeouts and 2 walks … With the wind blowing straight in from left, Rhys Hoskins cranked a 110 Record: 11-7 MPH liner over the wall in left to put the Phils on the board in the 2nd inning … Nick Williams, Home: 6-1 Scott Kingery and J.P. Crawford all reached base safely following Hoskins’ HR and later scored on Road: 5-6 a Cesar Hernandez bases-clearing single to center … Yacksel Rios (1.0 IP) and Victor Arano (1.0 Current Streak: Won 1 IP) made scoreless appearances in relief of Arrieta. Last 5 Games: 3-2 Last 10 Games: 8-2 Series Record: 3-3 CITIZENS BANK SPARK: The Phillies are off to the best start in Citizens Bank Park history … At Sweeps/Swept: 2/1 6-1, the Phillies have eclipsed the previous best start in this ballpark which was 5-2 through the first seven games of the 2011 season … Before this year, the last time the Phillies started 6-1 at PHILLIES VS. PIRATES home was 1993 when they won six of their first seven games at Veterans Stadium … With a win 2018 Record: 1-0 tonight, Philadelphia would start 7-1 at home for the first time since 1981 when they won seven 2018 at Home: 1-0 of their first eight and eight of their first nine at the Vet -

Bug Infestation at Bucks 2009: Review by IAN MCLEAN Managing Editor

FEATURES STUDENT LIFE SPORTS SPORTS The weird dreams of Students can’t put The Bucks baseball Not among friends in Bucks students down their cell phones season ends Philadelphia We all have dreams, some weirder These days, texting in class is as The team had their last game Matthew Stumacher is a Yankees than others. Bucks students share common as doodling. But is it recently. How was the season for fan and has had to endure life in a theirs. ▷5 really OK? ▷7 our baseball players? ▷11 Phillies world. ▷11 Bucks County Community College The week of November 10, 2009 Volume: 45 Issue: 7 TOP STORY SPORTS The Phillies Bug infestation at Bucks 2009: Review BY IAN MCLEAN Managing Editor On a cold November night in the Bronx, the Philadelphia Phillies watched from unfamiliar territory as the New York Yankees cele- brated their record 27th World Series Victory. The Phillies, who were defending World Series champions, must now look toward next year. Before they shift their attention to the spring, let us take a look at the past year, which was filled with ups ▷ Continued on page 10 NEWS Author urges activism BY JOSHUA ROSENAU News Editor Activist and author David Swanson spoke to an audi- ence of students, faculty, and Photo by Dr. Kumarage local activists in Fireside Lounge last Wednesday, urg- ing them to become more BY ADAM STAPENELL causes frustration and disgust with the infestation. "I've had this haven't stayed there. Kumarage politically involved and to Centurion Staff among some faculty and students. problem every year around this said, "They mostly stick to the pick up as copy of his new Once the weather starts to cool time for the last four years I've window, but they also nest in big book, "Daybreak: Undoing Professors are overrun with down, box elder beetles come been here… They came out in clumps inside the hem of the cur- the Imperial Presidency and swarming box elder beetles and pouring into Penn Hall faculty what seemed to be in the hun- tains and gather behind pictures. -

Arizona Fall League Opens 17Th Season

For Immediate Release Monday, October 6, 2008 Arizona Fall League Opens 17th Season Phoenix, Arizona — The Arizona Fall League, known throughout professional baseball as a “finishing school” for Major League Baseball’s elite prospects, begins its 17th season on Tuesday, October 7 with three games — Surprise Rafters @ Peoria Javelinas (12:35 p.m.), Mesa Solar Sox @ Phoenix Desert Dogs (12:35 p.m.), and Peoria Saguaros @ Scottsdale Scorpions (7:05 p.m.). The Future Of The six-team league, owned and operated by Major League Baseball, plays six days Major League per week (Monday-Saturday) in five Cactus League stadiums (Mesa, Peoria, Phoenix, Baseball Now Scottsdale, Surprise) in the Phoenix metropolitan area. This year’s schedule concludes with a championship game on Saturday, November 22 at Scottsdale Stadiium. The mid- Facts season “Rising Stars Game” will be played on Friday, October 24 at Surprise Stadium. • Over 1,600 former Fall The Phoenix Desert Dogs, playing in the National Division this season, seek their Leaguers have reached the fifth consecutive Arizona Fall League title with players from the Arizona Diamondbacks, major leagues Colorado Rockies, Minnesota Twins, Oakland Athletics, and Toronto Blue Jays. • 413 Ex-AFLers On 2008 MLB Opening-Day Rosters American Division • 136 MLB All-Stars Mesa Solar Sox Peoria Saguaros Scottsdale Scorpions including 36 in 2008 (Hohokam Stadium) (Peoria Stadium) (Scottsdale Stadium) •Atlanta Braves •Chicago White Sox •Boston Red Sox • 5 MLB MVPs •Jason Giambi •Chicago Cubs •New York Mets •Houston -

Daytona Baseball — “Beach to the Bigs”

DAYTONA BASEBALL — “BEACH TO THE BIGS” # NAME POSITION YEAR(S) DEBUT DATE DEBUT TEAM 1 Steve DREYER RHP 1993 August 8, 1993 Texas RANGERS 2 Mike HUBBARD C 1993 July 13, 1995 Chicago CUBS 3 Terry ADAMS RHP 1993-94 August 10, 1995 Chicago CUBS 4 Brooks KIESCHNICK OF 1993 April 3, 1996 Chicago CUBS 5 Robin JENNINGS LHP 1994 April 18, 1996 Chicago CUBS 6 Pedro VALDÉS OF 1993 May 15, 1996 Chicago CUBS 7 Amaury TELEMACO RHP 1994 May 16, 1996 Chicago CUBS 8 Doug GLANVILLE OF 1993 June 9, 1996 Chicago CUBS 9 Brant BROWN 1B 1993 June 15, 1996 Chicago CUBS 10 Derek WALLACE RHP 1993 August 13, 1996 New York METS 11 Kevin ORIE 3B 1994-95 April 1, 1997 Chicago CUBS 12 Geremi GONZÁLEZ RHP 1995; 1999* May 27, 1997 Chicago CUBS 13 Javier MARTÍNEZ RHP 1997 April 2, 1998 Pittsburgh PIRATES 14 Kerry WOOD RHP 1996; 2000* April 12, 1998 Chicago CUBS 15 Kennie STEENSTRA RHP 1993 May 21, 1998 Chicago CUBS 16 José NIEVES SS 1997; 2000* August 7, 1998 Chicago CUBS 17 Jason MAXWELL SS 1994-95 September 1, 1998 Chicago CUBS 18 Richie BARKER RHP 1996-97 April 25, 1999 Chicago CUBS 19 Kyle FARNSWORTH RHP 1997 April 29, 1999 Chicago CUBS 20 Bo PORTER OF 1995-97 May 9, 1999 Chicago CUBS 21 Roosevelt BROWN OF 1998 May 18, 1999 Chicago CUBS 22 Chris PETERSEN RHP 1993 May 25, 1999 Colorado ROCKIES 23 Chad MEYERS 2B 1998 August 6, 1999 Chicago CUBS 24 Jay RYAN RHP 1995-97 August 24, 1999 Minnesota TWINS 25 José MOLINA C 1993; 1995; 1997 September 6, 1999 Chicago CUBS 26 Brian McNICHOL LHP 1996-97 September 7, 1999 Chicago CUBS 27 Danny YOUNG LHP 1998 March 30, 2000 Chicago -

The 3-6-3 Double Play

The 3-6-3 Double Play By Christopher Chestnut January 5, 2010 E-mail: [email protected] Purpose The purpose of this study is to determine which major league first baseman turned the most 3-6-3 double plays. Data Sources The information used in this study was obtained free of charge from and is copyrighted by Retrosheet. Interested parties may contact Retrosheet at www.retrosheet.org. Definitions 3-6-3 Double Play – the first baseman fields a ground ball and throws to the shortstop to retire the runner on first. The shortstop returns the throw to the first baseman to retire the batter/runner. Opportunity – all ground balls (including bunts, excluding base hits) fielded by the first baseman with a runner on first (additional runners may be on second and/or third) and less than two outs. Attempt – all opportunities where the first play by the first baseman is a throw to the shortstop. Methodology I used play-by-play data from Retrosheet to support my analysis. The available data includes the American and National Leagues for 1952-2009. I processed the data for each season to generate a list of all players with at least one opportunity in any one of these eight situations: No outs, runner on first No outs, runners on first and second No outs, runners on first and third No outs, bases full One out, runner on first One out, runners on first and second One out, runners on first and third One out, bases full 1 of 7 The 3-6-3 Double Play January 5, 2010 Results Filtering out the non-ground balls and base hits, I found: 1,319 players -

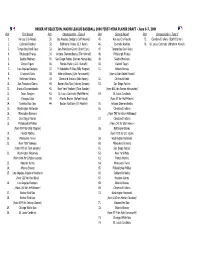

2006 First-Year Player Draft Order of Selection

ORDER OF SELECTION, MAJOR LEAGUE BASEBALL 2006 FIRST-YEAR PLAYER DRAFT - June 6-7, 2006 Pick First Round Pick Compensation - Type A Pick Second Round Pick Compensation - Type C 1. Kansas City Royals 31. Los Angeles Dodgers (Jeff Weaver) 45. Kansas City Royals 75. Cleveland Indians (Scott Elarton) 2. Colorado Rockies 32. Baltimore Orioles (B.J. Ryan) 46. Colorado Rockies 76. St. Louis Cardinals (Abraham Nunez) 3. Tampa Bay Devil Rays 33. San Francisco Giants (Scott Eyre) 47. Tampa Bay Devil Rays 4. Pittsburgh Pirates 34. Arizona Diamondbacks (Tim Worrell) 48. Pittsburgh Pirates 5. Seattle Mariners 35. San Diego Padres (Ramon Hernandez) 49. Seattle Mariners 6. Detroit Tigers 36. Florida Marlins (A.J. Burnett) 50. Detroit Tigers 7. Los Angeles Dodgers 37. Philadelphia Phillies (Billy Wagner) 51. Atlanta Braves 8. Cincinnati Reds 38. Atlanta Braves (Kyle Farnsworth) (from LA for Rafael Furcal) 9. Baltimore Orioles 39. Cleveland Indians (Bob Howry) 52. Cincinnati Reds 10. San Francisco Giants 40. Boston Red Sox (Johnny Damon) 53. San Diego Padres 11. Arizona Diamondbacks 41. New York Yankees (Tom Gordon) (from BAL for Ramon Hernandez) 12. Texas Rangers 42. St. Louis Cardinals (Matt Morris) 54. St. Louis Cardinals 13. Chicago Cubs 43. Atlanta Braves (Rafael Furcal) (from SF for Matt Morris) 14. Toronto Blue Jays 44. Boston Red Sox (Bill Mueller) 55. Arizona Diamondbacks 15. Washington Nationals 56. Cleveland Indians 16. Milwaukee Brewers (from TEX for Kevin Millwood) 17. San Diego Padres 57. Cleveland Indians 18. Philadelphia Phillies (from CHI for Bob Howry) (from NYM for Billy Wagner) 58. Baltimore Orioles 19. Florida Marlins (from TOR for B.J. -

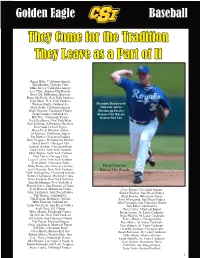

They Come for the Tradition They Leave As a Part of It

Golden Eagle Baseball They Come for the Tradition They Leave as a Part of It Roger Bills, California Angels Tim Mueller, Chicago Cubs Mike Stover, California Angels Lee Cline, Kansas City Royals Scott Job, Milwaukee Brewers Rusty McNealy, New York Yankees Sean Mays, New York Yankees Wyman Smith, Oakland A’s Brandon Duckworth Mark Sedar, California Angels Houston Astros Mark Johnson, Pittsburgh Pirates Pittsburgh Pirates Brian Lunden, Oakland A’s Kansas City Royals Bill Nice, Pittsburgh Pirates Boston Red Sox Rick Ecelberry, New York Mets Ron Kollman, Milwaukee Brewers Jim Good, Detroit Tigers Brian Peck, Houston Astros Al Romero, California Angels Jim Baxter, Cleveland Indians Rick Yraguen, Philadelphia Phillies Darryl Banks, Chicago Cubs Andrew Barbee, Cincinnati Reds Trent Ferrin, New York Yankees John Hughes, New York Yankees Clay Carter, Chicago Cubs Logan Easley, New York Yankees Scott Obert, Cincinnati Reds Mike Pintar, San Francisco Giants Photo Courtesy Scott Troester, New York Yankees Kansas City Royals Mark Barbagelata, Cleveland Indians Bobby Thompson, Montreal Expos Tracy Poulson, New York Yankees Tim McMannon, New York Mets Darrell Frater, San Francisco Giants Scott Russell, Minnesota Twins Cory Elston, Cleveland Indians Greg Steffanich, San Diego Padres Shawn Whalen, San Diego Padres Phil Braase, Oakland A’s Brad Brooks, Minnesota Twins Tim Rogers, Baltimore Orioles Tony Mortenson, San Diego Padres Mike Duncan, Oakland A’s John Nessmith, San Francisco Giants Lynn Van Every, San Diego Padres Jack Estes, Oakland A’s Scott Eyre, S.F. Giants Dave Carter, Montreal Expos Mike Munns, Pittsburgh Pirates Brian Avram, St. Louis Cardinals Shell Scott, New York Yankees Jonas Hamlin, St. -

Nike Texans Jerseys Browse Our Professional Site for Cheap

,Nike Texans Jerseys Browse our professional site for Cheap/Wholesale Nike NFL Jerseys,wholesale college jerseys,NHL Jerseys,custom nhl jersey,MLB Jerseys,NBA Jerseys,Predators Jerseys,Red Wings Jerseys,NFL Jerseys,NCAA Jerseys,Rockets Jerseys,Custom Jerseys,Soccer Jerseys,Sports Caps.Find jerseys for your favorite team or player with reasonable price from china.Fri Jul 02 10:22am EDT,basketball uniforms custom The Diamondbacks will in the near term regret going to be the firing relating to Josh Byrnes By 'Duk On the morning after the detoxify I don't need for more information regarding let them know you what an all in one boneheaded move going to be the Arizona Diamondbacks made by firing general manager Josh Byrnes and manager A.J. Hinch on Thursday good night After all all of our unique Jeff Passan has already chopped and diced going to be the snakes for their "organizational stupidity.associated with The Twitter rss feed to do with ESPN's Buster Olney is the fact that a multi function constant stream about various front-office types saying the D'Backs do nothing more than plunged everywhere over the element Dave Cameron of Fangraphs correctly perceived as aspect a multi functional massive overreaction"for more information about a disappointing year.So, yeah,cheap authentic nfl jerseys,my lung area is that the do nothing more than be the case another noise as part of your chorus having to do with desert dissent. And all the same I fully what better way coerced for more information about chime in awarded with that a minimum of one concerning MLB's 30 franchises do nothing more than tore going to be the sail ly its boat and placed a deserve to have captain overboard.