Papers for Meeting 8 January 2020

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2331 03 May 2021

Office of the Traffic Commissioner Scotland Notices and Proceedings Publication Number: 2331 Publication Date: 03/05/2021 Objection Deadline Date: 24/05/2021 Correspondence should be addressed to: Office of the Traffic Commissioner (Scotland) Hillcrest House 386 Harehills Lane Leeds LS9 6NF Telephone: 0300 123 9000 Website: www.gov.uk/traffic-commissioners The next edition of Notices and Proceedings will be published on: 03/05/2021 Publication Price £3.50 (post free) This publication can be viewed by visiting our website at the above address. It is also available, free of charge, via e-mail. To use this service please send an e-mail with your details to: [email protected] Remember to keep your bus registrations up to date - check yours on https://www.gov.uk/manage-commercial-vehicle-operator-licence-online PLEASE NOTE THE PUBLIC COUNTER IS CLOSED AND TELEPHONE CALLS WILL NO LONGER BE TAKEN AT HILLCREST HOUSE UNTIL FURTHER NOTICE The Office of the Traffic Commissioner is currently running an adapted service as all staff are currently working from home in line with Government guidance on Coronavirus (COVID-19). Most correspondence from the Office of the Traffic Commissioner will now be sent to you by email. There will be a reduction and possible delays on correspondence sent by post. The best way to reach us at the moment is digitally. Please upload documents through your VOL user account or email us. There may be delays if you send correspondence to us by post. At the moment we cannot be reached by phone. -

Press Release

Press Release 29th May 2014 For immediate release £75 million Investment in Four HUT Shopping Park Extensions Almost 300,000 sq ft of development works underway Hercules Unit Trust (HUT), the specialist retail park fund advised by British Land and managed by Schroders, is pleased to announce that construction work has started on four extensions to existing schemes across its portfolio. Work is underway on a 112,000 sq ft retail extension at Glasgow Fort, a 71,000 sq ft extension at Deepdale Shopping Park in Preston and leisure extensions of 55,000 sq ft at Fort Kinnaird in Edinburgh and 55,000 sq ft at Broughton Shopping Park in Chester. The extensions have a total cost of £75 million and will create more than a thousand new retail jobs locally, as well as temporary positions during the construction phase. The £35.5 million Glasgow Fort retail extension comprises an 80,000 sq ft anchor store which has been pre-let to M&S and a further 32,250 sq ft of retail and food and beverage space. The £14 million extension at Deepdale Shopping Park in Preston, which is 50% owned by HUT, will deliver 44,897 sq ft of additional retail space, which is 100% pre-let, and 28,658 sq ft of ancillary uses. The retailers to open at the extension are Wren Kitchens, Sofaworks, Harveys and Oak Furniture Land. The £12.5 million leisure extension at Broughton Shopping Park in Chester will include an 11- screen Cineworld IMAX cinema and five high quality family restaurants including PizzaExpress, Frankie & Benny’s, Chiquito and Nando’s. -

Mobile Order (Via Costa App) Aberdeen

Mobile order (via Costa app) Aberdeen - Bon Accord Centre AB25 1HZ Aberdeen - Cults AB15 9SD Aberdeen - Union Square AB11 5PS Aberdeen Bridge of Don DT AB23 8JW Aberdeen, Abbotswell Rd, DT AB12 3AD Aberdeen, Beach Boulevard RP, 1A AB11 5EJ Aberdeen, Marischal Sq AB10 1BL Aberdeen, Next, Berryden Rd, 4 AB25 3SG Aberdeen, Westhill SC, 27 AB32 6RL Abergavenny NP7 5RY Abergavenny, Head of the Valleys DT NP7 9LL Aberystwth SY23 1DE Aberystwyth Parc Y Llyn RP, Next SY23 3TL Accrington BB5 1EY Accrington, Hyndburn Rd, DT BB5 4AA Alderley Edge SK9 7DZ Aldershot GU11 1EP Alnwick NE66 1HZ Altrincham, Sunbank Lane, DT WA15 0AF Amersham HP6 5EQ Amersham - Tesco HP7 0HA Amesbury Drive Thru SP4 7SQ Andover SP10 1NF Andover BP DT SP11 8BF Andover, Andover Bus Station SP10 1QP Argyll Street W1F 7TH Ascot SL5 7HY Ashbourne DE6 1GH Ashford Int Station TN23 1EZ Ashford RP TN24 0SG Ashord - Tesco TN23 3LU Ashton OL6 7JJ Ashton Under Lyne DT OL7 0PG Atherstone, Grendon, Watling St, DT CV9 2PY Aviemore, Aviemore RP, U4 PH22 1RH Aylesbury HP20 1SH Aylesbury - Tesco HP20 1PQ Aylesbury Shopping Park HP20 1DG Ayr - Central, Teran Walk KA7 1TU Ayr - Heathfield Retail Park KA8 9BF Bagshot DT GU19 5DH Baker Street W1U 6TY Bakewell, King St DE45 1DZ Baldock SG7 6BN Banbury OX16 5UW Banbury Cross RP OX16 1LX Banbury, Stroud Park DT OX16 4AE Bangor LL57 1UL Bangor RP - Next LL57 4SU Banstead SM7 2NL Barking - Tesco IG11 7BS Barkingside IG6 2AH Barnard Castle DL12 8LZ Barnsley S70 1SJ Barnsley J36 DT Barnsley, Birdwell, Kestrel Way, DT S70 5SZ Barnstaple EX31 1HX Barnstaple -

Edinburgh City Cycleways Innertube and Little France Park

Edinburgh City Cycleways Innertube 50 51 49 52 LINDSAY RD CRAMOND VILLAGE MARINE DR HAWTHORNVALE WEST HARBOUR RD (FOR OCEAN TERMINAL) CRAIGHALL RD WEST SHORE RD 25 VICTORIA PARK / NEWHAVEN RD and Little France Park Map CRAMOND 2 WEST SHORE RD (FOR THE SHORE) FERRY RD SANDPORT PL CLARK RD LOWER GRANTON RD TRINITY CRES 472 SALTIRE SQ GOSFORD PL 48 TRINITY RD SOUT CONNAUGHT PL WARDIE RD H WATERFRONT AVE BOSWALL TER STEDFASTGATE WEST BOWLING COBURG ST 24 EAST PILTON FERRY RD ST MARKʼS PARK GREEN ST / (FOR GREAT 4 MACDONALD RD PILRIG PARK JUNCTION ST) (FOR BROUGHTON RD / LEITH WALK) DALMENY PARK CRAMOND BRIG WHITEHOUSE RD CRAMONDDAVIDSONʼS RD SOUTH MAINS / PARK WEST PILTON DR / WARRISTON RD SILVERKNOWES RD EAST / GRANTON RD SEAFIELD RD SILVERKNOWES ESPLANADE / / CRAMOND FORESHORE EILDON ST WARRISTON GDNS 26 TO SOUTH QUEENSFERRY WEST LINKS PL / & FORTH BRIDGES GRANTON LEITH LINKS SEAFIELD PL HOUSE Oʼ HILL AVE ACCESS INVERLEITH PARK 1 76 5 (FOR FERRY RD) 3 20 27 CRAIGMILLAR ROYAL BOTANIC GARDEN BROUGHTON RD 21 WARRISTON CRES WESTER DRYLAW DR T WARRISTON RD FERRY RD EAS FILLYSIDE RD EASTER RD / THORNTREEHAWKHILL ST AVERESTALRIG / RD FINDLAY GDNS CASTLE PARK 45 SCOTLAND ST (FOR LEITH WALK)LOCHEND PARK WESTER DRYLAW DR EASTER DRYLAW DR (FOR NEW TOWN) WELLINGTON PL 1 6 54 46 7 SEAFIELD RD 53 KINGS RD TELFORD DR 28 WESTER DRYLAW ROW (FOR WESTERN (FOR TELFORD RD) GENERAL HOSPITAL) (FOR STOCKBRIDGE) / 44 BRIDGE ST / HOLYROOD RD / DYNAMIC EARTH EYRE PL / KING GEORGE V PARK 56 MAIDENCRAIG CRES / DUKEʼS WALK CRAIGLEITH RETAIL PARK ROSEFIELD PARK FIGGATE -

June 2018 • £8.00 Tipping Point for Landfill

SHOPPINGCENTREThe business of retail destinations www.shopping-centre.co.uk June 2018 • £8.00 Tipping point for landfill Technology diverts food waste from landfill 10 Development 12 Sustainability 17 Parking Intu Watford Centres face food Global tech alliance nears completion waste challenge to streamline parking The Highcross Beacons, @HXBeacons Creative LED solutions to make spaces and places memorable. ADI design content-driven experiences and exceptional digital installations that deliver the unexpected. We combine giant LED platforms with larger-than-life creative to drive large scale IRKEKIQIRXERHMRXIVEGXMSR8SƼRHSYX more visit www.adi.tv/shoppingcentre For more information visit www.adi.tv/shoppingcentre 0800 592 346 | [email protected] | www.adi.tv CONTENTS Editor’s letter Editor Graham Parker 07956 231 078 Fraser is widely forecast to be Wolfson has complained that [email protected] next, with as many as 30 stores a two-tier market is emerging Editorial Assistant earmarked for closure. with retailers paying widely dif- Iain Hoey However the CVA is a form ferent rents for adjacent stores 07757 946 414 of insolvency and the question depending on whether or not [email protected] has to be asked whether these they have been through a CVA. Sales Manager businesses are in fact insolvent. He’s now inserting CVA clauses Trudy Whiston In the end that’s a decision for into leases allowing Next to 01293 416 090 [email protected] lawyers and accountants and claim a rent cut if a neighbour- not magazine editors, but the ing brand wins one through a Database Manager At last there are signs that land- suspicion is that companies CVA. -

Whsmith Store Address List

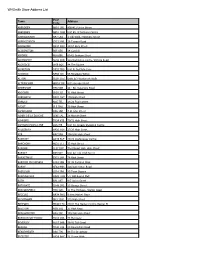

WHSmith Store Address List Post Town Address Code ABERDEEN AB10 1PD 408/412 Union Street ABERDEEN AB10 1HW Unit E5, St Nicholas Centre ABERGAVENNY NP7 5AG 1 Cibi Walk, Frogmore Street ABERYSTWYTH SY23 2AB 36 Terrace Road ABINGDON OX14 3QX 13/14 Bury Street ACCRINGTON BB5 1EX 14 Cornhill AIRDRIE ML6 6BU 60-62 Graham Street ALDERSHOT GU11 1DB 12a Wellington centre, Victoria Road ALDRIDGE WS9 8QS 44 The Square ALFRETON DE55 7BQ Unit B, Institute Lane ALNWICK NE66 1JD 56 Bondgate Within ALTON GU34 1HZ Units 6/7 Westbrook Walk ALTRINCHAM WA14 1SF 8/12 George Street AMERSHAM HP6 5DR 48 - 50, Sycamore Road ANDOVER SP10 1LJ 31 High Street ARBROATH DD11 1HY 196 High Street ARNOLD NG5 7EL 24/26 Front Street ASCOT SL5 7HG 39 High Street ASHBOURNE DE6 1GH 4 St John Street ASHBY DE LA ZOUCHE LE65 1AL 28 Market Street ASHFORD TN24 8TB 70/72 High Street ASHTON-UNDER-LYNE OL6 7JE Unit 30, Arcade Shopping Centre AYLESBURY HP20 1SH 27/29 High Street AYR KA7 1RH 198/200 High Street BANBURY OX16 5UE 23/24 Castle Quay Centre BANCHORY AB31 5TJ 33 High Street BANGOR LL57 1NY The Market Hall, High Street BARNET EN5 5XY Unit 22 111 High Street BARNSTAPLE EX31 1HP 76 High Street BARROW-IN-FURNESS LA14 1DB 38-42 Portland Walk BARRY CF63 4HH 126/128 Holton Road BASILDON SS14 1BA 29 Town Square BASINGSTOKE RG21 7AW 5/7 Old Basing Mall BATH BA1 1RT 6/7 Union Street BATHGATE EH48 1PG 23 George Street BEACONSFIELD HP9 1QD 11 The Highway, Station Road BECCLES NR34 9HQ 9 New Market Place BECKENHAM BR3 1EW 172 High Street BEDFORD MK40 1TG 29/31 The Harpur Centre, Harpur -

Fort Kinnaird, Edinburgh

TO LET/FOR SALE – COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT SITES on behalf of WHITEHILL ROAD, FORT KINNAIRD, EDINBURGH A1 PARK & RIDE NEWCRAIGHALL TRAIN STATION A1 DEVELOPMENT SITE 1- 20 acres SITES AVAILABLE FROM 1 ACRE TO 20 ACRES www.coatesandco.net TO LET/FOR SALE – COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT SITES WHITEHILL ROAD, FORT KINNAIRD, EDINBURGH A1 PLOT E PLOT D PLOT C AREA: 2.97 PLOT A AREA: 1.52 PLOT B AREA: 1.47 AREA: 1.50 PLOT F AREA: 1.70 AREA: 1.32 PLOT G PLOT N AREA: 1.00 AREA: 1.55 PLOT K PLOT L AREA: 1.41 PLOT J PLOT I PLOT M AREA: 1.60 AREA: 1.45 AREA: 1.59 PLOT H AREA: 1.71 AREA: 1.00 Future Development Site WHITEHILL ROAD SITES AVAILABLE FROM 1 ACRE TO 20 ACRES www.coatesandco.net THE ABOVE SITE AREAS ARE FOR DEMONSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY TO LET/FOR SALE – COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT SITES WHITEHILL ROAD, FORT KINNAIRD, EDINBURGH A1 DU DDIN GSTON PARK SOUTH A6016 NEWCRAIGHALL ROAD PARK & RIDE NIDDRIE MAINS ROAD THE WISP NEWCRAIGHALL AD TRAIN STATION ALL RO NEWCRAIGH A1 DEVELOPMENT SITE WHITEHILL ROAD D 1- 20 acres WHITEHILL ROA SITES AVAILABLE FROM 1 ACRE TO 20 ACRES www.coatesandco.net THE ABOVE SITE AREAS ARE FOR DEMONSTRATIVE PURPOSES ONLY TO LET/FOR SALE – COMMERCIAL DEVELOPMENT SITES WHITEHILL ROAD, FORT KINNAIRD, EDINBURGH North queensferry M90 TO DUNDEE 54 MILES Queensferry 1A 1 A901 M9 A90 M90 A199 EDINBURGH Portobello A1 Newbridge Corstorphine A1 Musselburgh 1 Broxburn A8 Gorgie South Gyle Newcraighall Inveresk 2 Morningside Newington Caigmillar M8 TO A1 GLASGOW 1 A71 A7 M8 40 MILES DEVELOPMENT SITE 1- 20 acres A70 A701 Liberton A772 Danderhall -

Fort Kinnaird Trade Park 74 Newcraighall Road, Edinburgh Eh15 3Hs

TO LET - PRIME TRADE/INDUSTRIAL PREMISES UNDER OFFER Unit 6 FORT KINNAIRD TRADE PARK 74 NEWCRAIGHALL ROAD, EDINBURGH EH15 3HS • 11,550 SQ FT (1,068 SQ M) • COULD DIVIDE INTO TWO UNITS OF 5,775 SQ FT (534 SQ M) • RENT: ON APPLICATION TO LET - PRIME TRADE/INDUSTRIAL PREMISES NEWCRAIGHALL ROAD A1 A6095 NEWCRAIGHALL ROAD WHITEHILL ROAD Unit NEWCRAIGHALL ROAD 6 homestore WHITEHILL ROAD WHITEHILL ROAD Unit 6 FORT KINNAIRD TRADE PARK TO LET - PRIME TRADE/INDUSTRIAL PREMISES 74 NEWCRAIGHALL ROAD, EDINBURGH EH15 3HS LEITH A902 A199 Craigentinny FORT KINNAIRD TRADE PARK EDINBURGH A1 A199 A8 Musselburgh A6095 Newcraighall A1 A71 A70 A1 Blackford A6106 Kings Danderhall Knowe A702 Millerhill A701 Cousland A720 A720 A68 Dalkeith Swanston A701 A7 Unit 6 Bonnyrigg Mayfield FORT KINNAIRD TRADE PARK A702 LOCATION DESCRIPTION RATEABLE VALUE Fort Kinnaird Trade Park is situated on the south side of Newcraighall The unit provides a prominent trade premises looking directly onto An indication of the likely rateable value is available on request. Road and in amongst Fort Kinnaird Retail Park which is the largest Newcraighall Road. The unit is mid-terraced and of steel frame construction retail park in Scotland and the second largest in the UK with a total with a glazed pedestrian access and a loading door to the rear. The minimum EPC of 75 retail outlets which include M&S, Boots, Argos, Clarks, Costa, eaves height is 6m and there is plenty of car parking to the front and further A copy of the Energy Performance Certificate is also available on request. JD Sports, McDonalds, Mothercare, Mountain Warehouse, Next, car parking or circulation space for vehicles at the rear. -

Changes in Edinburgh's C.B.D

Changes in Edinburgh’s C.B.D. 1. The ST. James Centre. The St. James Centre was built at the top of Leith Street in the early 1970’s, to encourage economic growth in a part of the city which was very run –down. There were old tenements – these were knocked down, and the shopping centre and the St. James hotel were built. In the past 4 years, John Lewis, the major department store was completely refurbished and extended to compete with the arrival of the nearby Harvey Nicols store in 2005. 2. The Princes Mall Again to provide a warm inviting environment for shoppers, and to replace old railway sidings beside Waverly station, the Princes Mall was build in the early 1980’s to encourage economic growth in the city centre. This is currently undergoing major refurbishment, as it has faced very stiff competition from out of town shopping centres such as the Gyle and Fort Kinnaird. However, although it is now a government policy that no more out – of – town shopping centres are to be built it is perhaps too late for the Princes Mall as many of the units are currently lying empty. 3. Out of Town Shopping Malls, and the Edinburgh Business Park beside the Gyle have had a major effect on Edinburgh’s C.B.D. Some shops have relocated to the out-of-town malls as there is cheaper land, free parking, and good accessibility as they are located beside major road junctions. However, in many cases it is true to say that many shops have opened another branch and kept their city centre branch e.g. -

Rec/S5/19/Tb/Wpl/22 Rural Economy and Connectivity

REC/S5/19/TB/WPL/22 RURAL ECONOMY AND CONNECTIVITY COMMITTEE TRANSPORT (SCOTLAND) BILL – WORKPLACE PARKING LEVY AMENDMENTS SUBMISSION FROM BRITISH LAND On behalf of its retail assets in Scotland, which include Fort Kinnaird in Edinburgh and Glasgow Fort in east Glasgow, British Land welcomes the opportunity to submit a brief response to the Rural Affairs and Connectivity Committee’s Call for Evidence on the proposed introduction of a Workplace Parking Levy as part of the Transport (Scotland) Bill. British Land’s Scotland-based retail assets have been a genuine success story in recent years, both in terms of the significant opportunities for local employment they provide and the positive contribution they make, both economically and to the local communities where they are located. In Edinburgh, Fort Kinnaird directly employs 2,000 people and contributes £53million in gross value added to the Scottish economy every year. Working with local partners, the Fort Kinnaird Recruitment and Skills Centre has helped more than 3,200 people into work since 2013. Meanwhile, Glasgow Fort directly employs 2,500 people, 65% of whom live within 5km of the site in an area of east Glasgow that has one of the highest rates of multiple deprivation anywhere in Scotland. British Land is a member of the Scottish Retail Consortium and fully endorses the SRC’s own submission to the Call for Evidence. British Land has important concerns about the proposed introduction of a Workplace Parking Levy, which can be briefly summarised as follows: • Many employees at British Land sites work shift patterns during times when there is limited access to public transport. -

Fort Kinnaird

Assessing Our Contribution FORT KINNAIRD: A REVIEW Welcome Key stats For shoppers, cinema-goers Fort Kinnaird offers a great and retailers, Fort Kinnaird is shopping, dining and leisure a place with customers and experience, just off the A1 community at its heart. in Edinburgh. Providing 2,000 Jobs In my time here, I’ve witnessed It is home to some of the best directly at Fort Kinnaird Fort Kinnaird become the lifestyle known brands in the UK such as destination it is today. Along with Primark, Boots, Pizza Express our partners, we have introduced and Odeon Cinema. important training opportunities The centre is well connected for staff 3,200+ People such as our Recruitment & Skills and visitors, and provides a great Centre, which is now an integral place for people to come together. helped into work since 2013 through part of Fort Kinnaird and the local the on-site Recruitment & Skills We’re delighted to publish this community. review exploring our social, Centre, working with local partners I’m always so proud to assist the economic and environmental retailers of the future, to develop contributions, informed by a their skills and support them in study carried out by independent their chosen career path. economics consultancy, Regeneris. £53m Contribution to Edinburgh’s economy annually, Liam Smith Gross Value Added (GVA) Centre Director at Fort Kinnaird 4 • FORT KINNAIRD: OUR HISTORY FORT KINNAIRD: A REVIEW • 5 As partners in the community, we are Fort Kinnaird: committed to ensuring Fort Kinnaird is a great place to be. From 2014-2017, 2018 we invested over £17m in improvements Flagship Schuh and Our History and are continuing to work to update Schuh Kids opens and develop our centre. -

Revised Craigmillar Urban Design Framework 8 August 2013 Revised Craigmillar Urban Design Framework

Revised Craigmillar Urban Design Framework 8 August 2013 Revised Craigmillar Urban Design Framework Approved by Planning Committee on 8th August 2013 2 CONTENTS 1 INTRODUCTION 6 2 THE FRAMEWORK IN OUTLINE 14 3 HOUSING AND DESIGN 38 4 MOVEMENT 65 5 CENTRES & SERVICES 92 6 COMMUNITY FACILITIES 100 7 PARKS, OPEN SPACES AND ENVIRONMENT 113 8 BUSINESS AND EMPLOYMENT 135 9 DRAINAGE AND INFRASTRUCTURE 144 10 IMPLEMENTATION 152 Preface The Craigmillar Urban Design Framework (CUDF) is key to guiding regeneration across the Craigmillar area. Since its first publication in 2005 significant progress has been made in working towards creating a thriving community. However, the Council recognises that the CUDF isn’t a static document and that it must be reviewed and updated to meet ever changing demands. The Council has worked closely with local people to understand what works well and what is still required to ensure that the regeneration of Craigmillar makes the most of its assets. I’d like to thank all those who took part in shaping this document. This partnership working is achieving real results and I am delighted to hear so many positive comments about the regeneration so far. Lessons have been learnt, and by listening to the people and reviewing this document, improvements will be made and a revived Craigmillar will emerge. Councillor Ian perry Convenor of the Planning Committee 4 1 INTRODUCTION VISION AND KEY ELEMENTS The Craigmillar Urban Design Framework: INTRODUCTION Vision and key elements 1.1 This document is the revised version of the Craigmillar Urban Design Framework (CUDF). It continues to set out a vision and planning principles for development of the Craigmillar area, and supersedes the original 2005 version of the CUDF.