MICROCOMP Output File

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Long Red Thread How Democratic Dominance Gave Way to Republican Advantage in Us House of Representatives Elections, 1964

THE LONG RED THREAD HOW DEMOCRATIC DOMINANCE GAVE WAY TO REPUBLICAN ADVANTAGE IN U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ELECTIONS, 1964-2018 by Kyle Kondik A thesis submitted to Johns Hopkins University in conformity with the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Baltimore, Maryland September 2019 © 2019 Kyle Kondik All Rights Reserved Abstract This history of U.S. House elections from 1964-2018 examines how Democratic dominance in the House prior to 1994 gave way to a Republican advantage in the years following the GOP takeover. Nationalization, partisan realignment, and the reapportionment and redistricting of House seats all contributed to a House where Republicans do not necessarily always dominate, but in which they have had an edge more often than not. This work explores each House election cycle in the time period covered and also surveys academic and journalistic literature to identify key trends and takeaways from more than a half-century of U.S. House election results in the one person, one vote era. Advisor: Dorothea Wolfson Readers: Douglas Harris, Matt Laslo ii Table of Contents Abstract…………………………………………………………………………………....ii List of Tables……………………………………………………………………………..iv List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………..v Introduction: From Dark Blue to Light Red………………………………………………1 Data, Definitions, and Methodology………………………………………………………9 Chapter One: The Partisan Consequences of the Reapportionment Revolution in the United States House of Representatives, 1964-1974…………………………...…12 Chapter 2: The Roots of the Republican Revolution: -

Greenp Eace.Org /Kochindustries

greenpeace.org/kochindustries Greenpeace is an independent campaigning organization that acts to expose global environmental problems and achieve solutions that are essential to a green and peaceful future. Published March 2010 by Greenpeace USA 702 H Street NW Suite 300 Washington, DC 20001 Tel/ 202.462.1177 Fax/ 202.462.4507 Printed on 100% PCW recycled paper book design by andrew fournier page 2 Table of Contents: Executive Summary pg. 6–8 Case Studies: How does Koch Industries Influence the Climate Debate? pg. 9–13 1. The Koch-funded “ClimateGate” Echo Chamber 2. Polar Bear Junk Science 3. The “Spanish Study” on Green Jobs 4. The “Danish Study” on Wind Power 5. Koch Organizations Instrumental in Dissemination of ACCF/NAM Claims What is Koch Industries? pg. 14–16 Company History and Background Record of Environmental Crimes and Violations The Koch Brothers pg. 17–18 Koch Climate Opposition Funding pg. 19–20 The Koch Web Sources of Data for Koch Foundation Grants The Foundations Claude R. Lambe Foundation Charles G. Koch Foundation David H. Koch Foundation Koch Foundations and Climate Denial pg. 21–28 Lobbying and Political Spending pg. 29–32 Federal Direct Lobbying Koch PAC Family and Individual Political Contributions Key Individuals in the Koch Web pg. 33 Sources pg. 34–43 Endnotes page 3 © illustration by Andrew Fournier/Greenpeace Mercatus Center Fraser Institute Americans for Prosperity Institute for Energy Research Institute for Humane Studies Frontiers of Freedom National Center for Policy Analysis Heritage Foundation American -

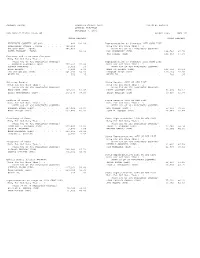

Results-Summary-Gen06 (PDF)

SUMMARY REPORT FRANKLIN COUNTY OHIO OFFICIAL RESULTS GENERAL ELECTION NOVEMBER 7, 2006 RUN DATE:11/29/06 08:45 AM REPORT-EL45 PAGE 001 VOTES PERCENT VOTES PERCENT PRECINCTS COUNTED (OF 842). 842 100.00 Representative to Congress 12TH CONG DIST REGISTERED VOTERS - TOTAL . 766,652 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 BALLOTS CAST - TOTAL. 385,863 (WITH 367 OF 367 PRECINCTS COUNTED) VOTER TURNOUT - TOTAL . 50.33 BOB SHAMANSKY (DEM) . 108,746 42.70 PAT TIBERI (REP) . 145,943 57.30 Governor and Lieutenant Governor (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (WITH 835 OF 835 PRECINCTS COUNTED) Representative to Congress 15TH CONG DIST J. KENNETH BLACKWELL (REP). 122,601 32.80 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 ROBERT FITRAKIS . 3,703 .99 (WITH 434 OF 434 PRECINCTS COUNTED) BILL PEIRCE. 5,382 1.44 MARY JO KILROY (DEM). 109,659 49.58 TED STRICKLAND (DEM). 241,536 64.62 DEBORAH PRYCE (REP) . 110,714 50.06 WRITE-IN. 553 .15 WRITE-IN. 783 .35 Attorney General State Senator 03RD OH SEN DIST (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (WITH 835 OF 835 PRECINCTS COUNTED) (WITH 316 OF 316 PRECINCTS COUNTED) MARC DANN (DEM) . 187,191 51.07 DAVID GOODMAN (REP) . 71,874 54.12 BETTY MONTGOMERY (REP) . 179,370 48.93 EMILY KREIDER (DEM) . 60,927 45.88 Auditor of State State Senator 15TH OH SEN DIST (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (Vote For Not More Than ) 1 (WITH 835 OF 835 PRECINCTS COUNTED) (WITH 251 OF 251 PRECINCTS COUNTED) BARBARA SYKES (DEM) . -

Appendix File 1982 Merged Methods File

Page 1 of 145 CODEBOOK APPENDIX FILE 1982 MERGED METHODS FILE USER NOTE: This file has been converted to electronic format via OCR scanning. As as result, the user is advised that some errors in character recognition may have resulted within the text. >> ABOUT THE EXPRESSIONS IN THE 1982 QUESTIONNAIRE (NAME Y X, Y. OR Z) The 1982 tIME sERIES questionnaire made provisions to have interviewers fill in district/state candidate names in blank slots like the one depicted above. A comprehensive list of HOUSE, SENATE and GOVERNOR candidate and incumbent names was prepared for each of the 173 districts in the sample and the interviewers used the lists to pre-edit names where appropriate depending on the district of interview. These candidate lists are reproduced in the green pages section of this documentation. The (NAME #) expression will generally list more than one candidate number. For any given district, however, one of two possibilities will hold: 1) there will be one and only one name in the district candidate list qualifying for inclusion on the basis of the numbers listed in the expression; or 2) there will be no number in the district candidate list matching any of the numbers in the expression. An instance of no matching numbers arises for a question about the candidate challenging a district incumbent when, in fact, the incumbent is running unopposed. Interviewers were instructed to mark "NO INFO" those questions involving unmatched candidate numbers in the (NAME #) expression. In the candidate list, each candidate or incumbent is assigned a number or code. Numbers beginning with 1 (11-19) are for the Senate, numbers beginning with 3 (31-39) are for the House of Representatives, and numbers beginning with 5 (51-58) are for governors. -

Snake-Oil Economics

The second voice is that of the nu- Snake-Oil anced advocate. In this case, economists advance a point of view while recognizing Economics the diversity of thought among reasonable people. They use state-of-the-art theory and evidence to try to persuade The Bad Math Behind the undecided and shake the faith of Trump’s Policies those who disagree. They take a stand without pretending to be omniscient. N. Gregory Mankiw They acknowledge that their intellectual opponents have some serious arguments and respond to them calmly and without vitriol. Trumponomics: Inside the America First The third voice is that of the rah-rah Plan to Revive Our Economy partisan. Rah-rah partisans do not build BY STEPHEN MOORE AND their analysis on the foundation of profes- ARTHUR B. LAFFER. All Points sional consensus or serious studies from Books, 2018, 287 pp. peer-reviewed journals. They deny that people who disagree with them may have hen economists write, they some logical points and that there may be can decide among three weaknesses in their own arguments. In W possible voices to convey their view, the world is simple, and the their message. The choice is crucial, opposition is just wrong, wrong, wrong. because it affects how readers receive Rah-rah partisans do not aim to persuade their work. the undecided. They aim to rally the The first voice might be called the faithful. textbook authority. Here, economists Unfortunately, this last voice is the act as ambassadors for their profession. one the economists Stephen Moore and They faithfully present the wide range Arthur Laffer chose in writing their of views professional economists hold, new book, Trumponomics. -

Based Health Care Walter Williams Addresses Institute

The INDEPENDENT NEWSLETTER OF THE INDEPENDENT INSTITUTE VOLUME X, NUMBER 1 Walter Williams Book Seeks Market- Addresses Institute Based Health Care hould limits on government power be lifted n the U.S. today, one of every seven dollars Sto promote so-called “social justice”? Not Iof income is spent on health care. And, ac- if we hope to preserve our liberty and protect cording to a variety of measures, such as life equal rights, according to Walter Williams expectancy at birth or age 65, the American (George Mason University). At his July 20th ad- health care system performs poorly. The Inde- dress at the Independent Policy Forum entitled pendent Institute’s new book, AMERICAN “Liberty and the Failures of Government,” the HEALTH CARE: Government, Market Pro- popular economist and syndicated columnist argued that strict adherence to constitutional- ism is both a practical and moral imperative. Drawing on his book, More Liberty Means Less Government, Williams employed his strong Government, Market Processes, and the Public Interest Edited by Roger D. Feldman Foreword by Mark V. Pauly Noted economist, columnist, and author Walter Wil- liams addresses the Independent Policy Forum. logic and good humor to urge a return to the limited government envisioned by the Founders based on individual self-ownership. He ex- T H E I N D E P E N D E N T I N S T I T U T E plained the superiority of private to public pro- (continued on page 6) cesses, and the Public Interest, now explains why this high-cost system requires fundamen- tal reforms to improve access to high quality, IN THIS ISSUE: affordable health care. -

The Political Process

1980-81 Institute of Politics John F.Kennedy School of Government Harvard University PROCEEDINGS Institute of Politics 1980-81 John F. Kennedy School of Government Harvard University FOREWORD Here is Proceedings '81, the third edition of this annual retrospective of the Institute of Politics. It serves the function of an annual report, but it is more than that. Part One, "Readings," is a sampling of written and spoken words drawn from the many formats of Institute activity: panel discussions and speeches in our Forum, dialogue among conference participants, an essay from a faculty study group, stu dent writing from the Harvard Political Review, personal evalutions from a summer intern and from our resident Fellows, and so forth. They contain impassioned rhetoric from controversial figures as well as opinion and analysis from less well- known individuals. This year we even have a poem and a little humor. Taken together, the "Readings," represent a good cross-section of what happens here. Part Two, 'Programs," is a record of all the events sponsored by the Institute dur ing the 1980-81 academic year. This section delineates the participation of hundreds of individuals who together make the Institute the lively, interactive place that it is. Although they are not all captured on tape or on paper, their contributions make this place come alive, and this listing is a recognition of that. Thus, the annual editions of Proceedings provide an ongoing portrait of the In stitute of Politics. I hope you find it both informative and enjoyable. -

Declaration of Independence: End Corporate Welfare

Declaration of Independence: End Corporate Welfare EXECUTIVE SUMMARY................................................................................................................. 2 CORPORATE WELFARE VS. THE AMERICAN DREAM ............................................................. 3 FOOTPRINT OF CAPITALISM............................................................................................... 4 THE SLOWDOWN .......................................................................................................................... 4 GDP PER CAPITA GROWTH ................................................................................................ 4 CUT GOVERNMENT SPENDING................................................................................................... 5 INCOME TAXES THEN AND NOW ....................................................................................... 5 GOV’T SPENDING AS A % OF GDP..................................................................................... 6 CUT CORPORATE WELFARE ...................................................................................................... 6 SEMATECH: A SUBSIDY TO THE RICH ...................................................................................... 9 UNFAIR COMPETITION: THE ATP VIDEO COMPRESSION PROGRAM ................................. 10 SPENDING FOR NO BENEFIT: GALLIUM ARSENIDE WAFERS IN SPACE ........................... 11 SPENDING THAT HURTS THE BENEFICIARY: EUROPEAN SEMICONDUCTOR SUBSIDIES ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Stephen Moore: Obamanonics Vs. Reaganomics - WSJ.Com

Stephen Moore: Obamanonics vs. Reaganomics - WSJ.com http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424053111904875404... Dow Jones Reprints: This copy is for your personal, non-commercial use only. To order presentation-ready copies for distribution to your colleagues, clients or customers, use the Order Reprints tool at the bottom of any article or visit www.djreprints.com See a sample reprint in PDF format. Order a reprint of this article now OPINION AUGUST 26, 2011 Obamanonics vs. Reaganomics One program for recovery worked, and the other hasn't. By STEPHEN MOORE If you really want to light the fuse of a liberal Democrat, compare Barack Obama's economic performance after 30 months in office with that of Ronald Reagan. It's not at all flattering for Mr. Obama. The two presidents have a lot in common. Both inherited an American economy in collapse. And both applied daring, expensive remedies. Mr. Reagan passed the biggest tax cut ever, combined with an agenda of deregulation, monetary restraint and spending controls. Mr. Obama, of course, has given us a $1 trillion spending stimulus. By the end of the summer of Reagan's third year in office, the economy was soaring. The GDP growth rate was 5% and racing toward 7%, even 8% growth. In 1983 and '84 output was growing so fast the biggest worry was that the economy would "overheat." In the summer of 2011 we have an economy limping along at barely 1% growth and by some indications headed toward a "double-dip" recession. By the end of Reagan's first term, it was Morning in America. -

Trump Economic Advisory Council 1

TRUMP ECONOMIC ADVISORY COUNCIL 1. Tom Barrack. Thomas J Barrack Jr. is the Founder and Executive Chairman of Colony Capital, NYSE (CLNY). Colony is one of the oldest and most well-recognized private equity firms in the world. Prior to forming Colony, Mr. Barrack was a Principal of the Robert M. Bass Group and had served in the Regan administration as a Deputy Undersecretary of Interior. 2. Andy Beal. Beal is the founder and chairman of Beal Bank and Beal Bank USA as well as other affiliated companies including, CSG Investments, Inc., Loan Acquisition Corporation, and CLG Hedge Fund, LLC. Mr. Beal has been recognized as “one of the smartest investors in the country” by Forbes magazine and in 2000, American Banker named Beal Bank the most profitable bank in the USA. 3. Stephen M. Calk. Calk is the Founder, Chairman and CEO Federal Savings Bank, and National Bancorp Holdings, which is primarily focused on increasing home ownership among veterans of the Armed Forces. He is a commissioned Army Officer and received his M.B.A. from Northwestern University. Under his leadership, the Federal Savings Bank was named the most profitable bank in America in its class by the American Bankers Association Journal. 4. Dan DiMicco. DiMicco has served as Executive Chairman of the Nucor Corporation, the largest steel producer in America. He was the longest serving CEO of Nucor outside of the company’s founder. Mr. DiMicco has served on the board of the United States Manufacturing Council. He is the author of the book, American Made: Why Making Things Will Return Us To Greatness, which lays the blueprint of how to return America to economic prosperity through a revitalization of manufacturing. -

RSPS-3Rd-Edition.Pdf

d 3rd EDITION ON Ri h S P S Rich States, Poor States ALEC-LAFFER STATE ECONOMIC COMPETITIVENESS INDEX Salt Lake City, UT Minden, IA Detroit, MI Arthur B. Laffer Stephen Moore Jonathan Williams Foreword by Gov. Gary R. Herbert Rich States, Poor States ALEC-Laffer State Economic Competitiveness Index Arthur B. Laffer Stephen Moore Jonathan Williams Rich States, Poor States ALEC-Laffer State Economic Competitiveness Index © 2010 American Legislative Exchange Council All rights reserved. Except as permitted under the United States Copyright Act of 1976, no part of this publication may be reproduced or distributed in any form or by any means, or stored in a database or retrieval system without the prior permission of the publisher. Published by American Legislative Exchange Council 1101 Vermont Ave., NW, 11th Floor Washington, D.C. 20005 Phone: (202) 466-3800 Fax: (202) 466-3801 www.alec.org For more information, contact the ALEC Public Affairs office. Dr. Arthur B. Laffer, Stephen Moore and Jonathan Williams, Authors Designed for ALEC by Drop Cap Design • www.dropcapdesign.com ISBN: 978-0-9822315-5-5 Rich States, Poor States: ALEC-Laffer State Economic Competitiveness Index has been published by the American Legislative Exchange Council (ALEC) as part of its mission to discuss, develop, and disseminate public policies, which expand free mar- kets, promote economic growth, limit the size of government, and preserve individual liberty. ALEC is the nation’s largest nonpartisan, voluntary membership organization of state legislators, with 2,000 members across the nation. ALEC is governed by a Board of Directors of state legislators, which is advised by a Private Enterprise Board representing major corporate and foundation sponsors. -

2006 Primary Election Results

The Hannah Report Special Election Edition May 3, 2006 2006 Primary Election Results Party caucuses held a few surprises Tuesday. There were a number of anticipated blow-outs and several nail-biters, including a seven-way Democratic primary in the 10th House District that was still too close to call at end of business Wednesday. Results remain officially "unofficial" in all races and do not reflect provisional voting. Absentee ballots were also out in Cuyahoga County, where the election board was forced to count votes by hand in the 10th District and other races. A disclaimer at the secretary of state's website notes that results will be final 81 days after the date on which county boards of elections have all completed official canvases, which must be no later than May 23, 2006. Statewide Races U.S. Rep. Ted Strickland (D-Ohio) easily overcame his opponent to win the Democratic caucus for governor by a factor of four. Bryan Flannery was unable to capitalize on allegations concerning a former Strickland staffer arrested for public indecency. On the Republican side, Secretary of State Ken Blackwell banked on a well-organized and financially generous grassroots effort to pass Attorney General Jim Petro for the gubernatorial nomination. In the attorney general campaign, Sen. Tim Grendell (R-Chesterland) acknowledged the inevitability of former attorney general Betty Montgomery's bid for another Republican nomination to her old job, conceding early Tuesday to the sitting auditor. Among Democrats, former Cleveland law director Subodh Chandra won numerous newspaper endorsements -- though not his party's -- for attorney general, which was instead claimed by leading workers' comp critic Sen.