Commando Comics Abstract: for Generations of Australians and New Zealanders, Com- Mando Comics Have Provided a Consistent Image of Their Ancestors at War

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Comics and War

Representations of war Comics and War Mathieu JESTIN Bettina SEVERIN-BARBOUTIE ABSTRACT Recounting war has always played a role in European comics, whether as an instrument of propaganda, heroisation or denunciation. But it is only in recent decades that the number of stories about war has proliferated, that the range of subjects, spaces treated and perspectives has increased, and that the circulation of stories across Europe has become more pronounced. For this reason, comic books feed into a shared collection of popular narratives of war just as they fuel anti-war representations. "“Everyone Kaputt. The First World War in Comic Books.” Source: with the kind permission of Barbara Zimmermann. " In Europe, there is growing public interest in what is known in France as the ‘ninth art’. The publishing of comic books and graphic novels is steadily increasing, including a growing number which deal with historical subjects; comic book festivals are increasing in number and the audience is becoming larger and more diverse. Contrary to received ideas, the comic is no longer merely ‘an entertainment product’; it is part of culture in its own right, and a valid field of academic research. These phenomena suggest that the comic, even if it is yet to gain full recognition in all European societies, at least meets with less reticence than it faced in the second half of the twentieth century. It has evolved from an object arousing suspicion, even rejection, into a medium which has gained wide recognition in contemporary European societies. War illustrated: themes and messages As in other media in European popular culture, war has always been a favourite subject in comics, whether at the heart of the narrative or in the background. -

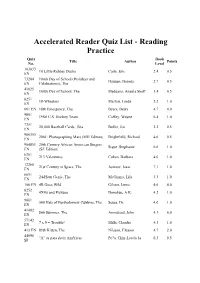

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No

Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. Level 103833 10 Little Rubber Ducks Carle, Eric 2.4 0.5 EN 73204 100th Day of School (Holidays and Haugen, Brenda 2.7 0.5 EN Celebrations), The 41025 100th Day of School, The Medearis, Angela Shelf 1.4 0.5 EN 8251 18-Wheelers Maifair, Linda 5.2 1.0 EN 661 EN 18th Emergency, The Byars, Betsy 4.7 4.0 9801 1980 U.S. Hockey Team Coffey, Wayne 6.4 1.0 EN 7351 20,000 Baseball Cards...Sea Buller, Jon 2.5 0.5 EN 900355 2061: Photographing Mars (MH Edition) Brightfield, Richard 4.6 0.5 EN 904851 20th Century African American Singers Sigue, Stephanie 6.6 1.0 EN (SF Edition) 6201 213 Valentines Cohen, Barbara 4.0 1.0 EN 12260 21st Century in Space, The Asimov, Isaac 7.1 1.0 EN 6651 24-Hour Genie, The McGinnis, Lila 3.3 1.0 EN 166 EN 4B Goes Wild Gilson, Jamie 4.6 4.0 8252 4X4's and Pickups Donahue, A.K. 4.2 1.0 EN 9001 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins, The Seuss, Dr. 4.0 1.0 EN 41482 $66 Summer, The Armistead, John 4.3 6.0 EN 57142 7 x 9 = Trouble! Mills, Claudia 4.3 1.0 EN 413 EN 89th Kitten, The Nilsson, Eleanor 4.7 2.0 44096 "A" es para decir Am?ricas Pe?a, Chin-Lee/de la 6.3 0.5 SP Accelerated Reader Quiz List - Reading Practice Quiz Book Title Author Points No. -

Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero This Page Intentionally Left Blank Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero Critical Essays

Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero This page intentionally left blank Captain America and the Struggle of the Superhero Critical Essays Edited by ROBERT G. WEINER Foreword by JOHN SHELTON LAWRENCE Afterword by J.M. DEMATTEIS McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Jefferson, North Carolina, and London ALSO BY ROBERT G. WEINER Marvel Graphic Novels and Related Publications: An Annotated Guide to Comics, Prose Novels, Children’s Books, Articles, Criticism and Reference Works, 1965–2005 (McFarland, 2008) LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGUING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Captain America and the struggle of the superhero : critical essays / edited by Robert G. Weiner ; foreword by John Shelton Lawrence ; afterword by J.M. DeMatteis. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-0-7864-3703-0 softcover : 50# alkaline paper ¡. America, Captain (Fictitious character) I. Weiner, Robert G., 1966– PN6728.C35C37 2009 741.5'973—dc22 2009000604 British Library cataloguing data are available ©2009 Robert G. Weiner. All rights reserved No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying or recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Cover images ©2009 Shutterstock Manufactured in the United States of America McFarland & Company, Inc., Publishers Box 6¡¡, Je›erson, North Carolina 28640 www.mcfarlandpub.com Dedicated to My parents (thanks for your love, and for putting up with me), and Larry and Vicki Weiner (thanks for your love, and I wish you all the happiness in the world). JLF, TAG, DW, SCD, “Lizzie” F, C Joyce M, and AH (thanks for your friend- ship, and for being there). -

110% Gaming 220 Triathlon Magazine 3D World Adviser

110% Gaming 220 Triathlon Magazine 3D World Adviser Evolution Air Gunner Airgun World Android Advisor Angling Times (UK) Argyllshire Advertiser Asian Art Newspaper Auto Car (UK) Auto Express Aviation Classics BBC Good Food BBC History Magazine BBC Wildlife Magazine BIKE (UK) Belfast Telegraph Berkshire Life Bikes Etc Bird Watching (UK) Blackpool Gazette Bloomberg Businessweek (Europe) Buckinghamshire Life Business Traveller CAR (UK) Campbeltown Courier Canal Boat Car Mechanics (UK) Cardmaking and Papercraft Cheshire Life China Daily European Weekly Classic Bike (UK) Classic Car Weekly (UK) Classic Cars (UK) Classic Dirtbike Classic Ford Classic Motorcycle Mechanics Classic Racer Classic Trial Classics Monthly Closer (UK) Comic Heroes Commando Commando Commando Commando Computer Active (UK) Computer Arts Computer Arts Collection Computer Music Computer Shopper Cornwall Life Corporate Adviser Cotswold Life Country Smallholding Country Walking Magazine (UK) Countryfile Magazine Craftseller Crime Scene Cross Stitch Card Shop Cross Stitch Collection Cross Stitch Crazy Cross Stitch Gold Cross Stitcher Custom PC Cycling Plus Cyclist Daily Express Daily Mail Daily Star Daily Star Sunday Dennis the Menace & Gnasher's Epic Magazine Derbyshire Life Devon Life Digital Camera World Digital Photo (UK) Digital SLR Photography Diva (UK) Doctor Who Adventures Dorset EADT Suffolk EDGE EDP Norfolk Easy Cook Edinburgh Evening News Education in Brazil Empire (UK) Employee -

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II a Master's Thesis Presented to College of Arts & Sciences Departmen

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II A Master’s Thesis Presented To College of Arts & Sciences Department of Communications and Humanities _______________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree _______________________________ SUNY Polytechnic Institute By David Dellecese May 2018 © 2018 David Dellecese Approval Page SUNY Polytechnic Institute DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS AND HUMANITIES INFORMATION DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY MS PROGRAM Approved and recommended for acceptance as a thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Design + Technology. _________________________ DATE ________________________________________ Kathryn Stam Thesis Advisor ________________________________________ Ryan Lizardi Second Reader ________________________________________ Russell Kahn Instructor 1 ABSTRACT American comic books were a relatively, but quite popular form of media during the years of World War II. Amid a limited media landscape that otherwise consisted of radio, film, newspaper, and magazines, comics served as a useful tool in engaging readers of all ages to get behind the war effort. The aims of this research was to examine a sampling of messages put forth by comic book publishers before and after American involvement in World War II in the form of fictional comic book stories. In this research, it is found that comic book storytelling/messaging reflected a theme of American isolation prior to U.S. involvement in the war, but changed its tone to become a strong proponent for American involvement post-the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This came in numerous forms, from vilification of America’s enemies in the stories of super heroics, the use of scrap, rubber, paper, or bond drives back on the homefront to provide resources on the frontlines, to a general sense of patriotism. -

British Library Conference Centre

The Fifth International Graphic Novel and Comics Conference 18 – 20 July 2014 British Library Conference Centre In partnership with Studies in Comics and the Journal of Graphic Novels and Comics Production and Institution (Friday 18 July 2014) Opening address from British Library exhibition curator Paul Gravett (Escape, Comica) Keynote talk from Pascal Lefèvre (LUCA School of Arts, Belgium): The Gatekeeping at Two Main Belgian Comics Publishers, Dupuis and Lombard, at a Time of Transition Evening event with Posy Simmonds (Tamara Drewe, Gemma Bovary) and Steve Bell (Maggie’s Farm, Lord God Almighty) Sedition and Anarchy (Saturday 19 July 2014) Keynote talk from Scott Bukatman (Stanford University, USA): The Problem of Appearance in Goya’s Los Capichos, and Mignola’s Hellboy Guest speakers Mike Carey (Lucifer, The Unwritten, The Girl With All The Gifts), David Baillie (2000AD, Judge Dredd, Portal666) and Mike Perkins (Captain America, The Stand) Comics, Culture and Education (Sunday 20 July 2014) Talk from Ariel Kahn (Roehampton University, London): Sex, Death and Surrealism: A Lacanian Reading of the Short Fiction of Koren Shadmi and Rutu Modan Roundtable discussion on the future of comics scholarship and institutional support 2 SCHEDULE 3 FRIDAY 18 JULY 2014 PRODUCTION AND INSTITUTION 09.00-09.30 Registration 09.30-10.00 Welcome (Auditorium) Kristian Jensen and Adrian Edwards, British Library 10.00-10.30 Opening Speech (Auditorium) Paul Gravett, Comica 10.30-11.30 Keynote Address (Auditorium) Pascal Lefèvre – The Gatekeeping at -

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 Less Doctor Who Except for 1975

ANNUALS-EXIT Total of 576 less Doctor Who except for 1975 Annual aa TITLE, EXCLUDING “THE”, c=circa where no © displayed, some dates internal only Annual 2000AD Annual 1978 b3 Annual 2000AD Annual 1984 b3 Annual-type Abba Gift Book © 1977 LR4 Annual ABC Children’s Hour Annual no.1 dj LR7w Annual Action Annual 1979 b3 Annual Action Annual 1981 b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 LR5 Annual TVT Adventures of Robin Hood 1 2, (1 for repair of other) b3 Annual TVT Adventures of Sir Lancelot circa 1958, probably no.1 b3 Annual TVT A-Team Annual 1986 LR4 Annual Australasian Boy’s Annual 1914 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual 1912 LR Annual Australian Boy’s Annual c/1930 plane over ship dj not matching? LR Annual Australian Girl’s Annual 16? Hockey stick cvr LR Annual-type Australian Wonder Book ©1935 b3 Annual TVT B.J. and the Bear © 1981 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1985 b3 Annual Battle Action Force Annual 1986 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1981 LR5 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 b3 Annual Battle Picture Weekly Annual 1982 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1964 LR5 Annual Beano Book 1971 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1981 b3 Annual Beano Book 1983 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1985 LR4 Annual Beano Book 1987 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1976 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1977 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1982 LR4 Annual Beezer Book 1987 LR4 Annual TVT Ben Casey Annual © 1963 yellow Sp LR4 Annual Beryl the Peril 1977 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual Beryl the Peril 1988 (Beano spin-off) b3 Annual TVT Beverly Hills 90210 Official Annual 1993 LR4 Annual TVT Bionic -

War Comics from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

War comics From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia War comics is a genre of comic books that gained popularity in English-speaking countries following War comics World War II. Contents 1 History 1.1 American war comics 1.2 End of the Silver Age 1.3 British war comics 2 Reprints 3 See also 4 References 5 Further reading 6 External links History American war comics Battlefield Action #67 (March 1981). Cover at by Pat Masulli and Rocco Mastroserio[1] Shortly after the birth of the modern comic book in the mid- to late 1930s, comics publishers began including stories of wartime adventures in the multi-genre This topic covers comics that fall under the military omnibus titles then popular as a format. Even prior to the fiction genre. U.S. involvement in World War II, comic books such as Publishers Quality Comics Captain America Comics #1 (March 1941) depicted DC Comics superheroes fighting Adolf Hitler and the Nazis. Marvel Comics Golden Age publisher Quality Comics debuted its title Charlton Comics Blackhawk in 1944; the title was published more or less Publications Blackhawk continuously until the mid-1980s. Sgt. Fury and his Howling Commandos In the post-World War II era, comic books devoted Sgt. Rock solely to war stories began appearing, and gained G.I. Combat popularity the United States and Canada through the 1950s and even during the Vietnam War. The titles Commando Comics tended to concentrate on US military depictions, Creators Harvey Kurtzman generally in World War II, the Korean War or the Robert Kanigher Vietnam War. Most publishers produced anthologies; Joe Kubert industry giant DC Comics' war comics included such John Severin long-running titles as All-American Men of War, Our Russ Heath Army at War, Our Fighting Forces, and Star Spangled War Stories. -

Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours

i Being a Superhero is Amazing, Everyone Should Try It: Relationality and Masculinity in Superhero Narratives Kevin Lee Chiat Bachelor of Arts (Communication Studies) with Second Class Honours This thesis is presented for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy of The University of Western Australia School of Humanities 2021 ii THESIS DECLARATION I, Kevin Chiat, certify that: This thesis has been substantially accomplished during enrolment in this degree. This thesis does not contain material which has been submitted for the award of any other degree or diploma in my name, in any university or other tertiary institution. In the future, no part of this thesis will be used in a submission in my name, for any other degree or diploma in any university or other tertiary institution without the prior approval of The University of Western Australia and where applicable, any partner institution responsible for the joint-award of this degree. This thesis does not contain any material previously published or written by another person, except where due reference has been made in the text. This thesis does not violate or infringe any copyright, trademark, patent, or other rights whatsoever of any person. This thesis does not contain work that I have published, nor work under review for publication. Signature Date: 17/12/2020 ii iii ABSTRACT Since the development of the superhero genre in the late 1930s it has been a contentious area of cultural discourse, particularly concerning its depictions of gender politics. A major critique of the genre is that it simply represents an adolescent male power fantasy; and presents a world view that valorises masculinist individualism. -

Exhibition Information

Exhibition Information Open daily 10:00-18:00 | Open late Thu 20:00 Festive opening times: Sat 24 and Sat 31 December: 10:00-16:30 Sun 25 and Mon 26 December: CLOSED 152 Nethergate, Dundee, DD1 4DY Sun 1 and Mon 2 January: CLOSED 01382 909900 | Scottish Charity No. SCO26631 Admission free | www.dca.org.uk INTRODUCTION Dundee Contemporary Arts is delighted to present DCA Thomson, featuring six contemporary artists’ responses to the extensive archives of the renowned publishers DC Thomson. The exhibition has been programmed in partnership with DC Thomson to celebrate the 80th anniversary of The Broons and Oor Wullie. The invited artists, Rabiya Choudhry, Rob Churm, Craig Coulthard, Malcy Duff, Hideyuki Katsumata and Sofia Sita, have each visited the DC Thomson archives and are exhibiting their own individual takes on the rich cultural history of our city’s publishing. The exhibition features murals, prints, drawings, sculpture and video alongside archive material. ARTISTS IN THE EXHIBITION RABIYA CHOUDHRY Edinburgh-based artist Rabiya Choudhry’s work takes inspiration from childhood memories and subconscious dreams. She has created new work for the exhibition loosely based on her own family and inspired by DC Thomson’s riotous comic strip The Numskulls, about a team of tiny human-like technicians who live inside people’s heads and run their bodies and minds. Choudhry’s own comic creation, The Coconuts, is the basis for a new pair of paintings in homage to The Numskulls. The paintings are titled dream baby dream and houses for the holy, in reference to songs by the bands Suicide and Led Zeppelin respectively. -

Showcase Presents: Batman: Volume 6 Free

FREE SHOWCASE PRESENTS: BATMAN: VOLUME 6 PDF Neal Adams,Frank Robbins,Dennis O'Neil | 584 pages | 02 Feb 2016 | DC Comics | 9781401251536 | English | United States Showcase Presents: Batman Vol. 6 (Collected) | DC Database | Fandom Title and company credits page with partial image from cover of Batman DC, series and indicia information. Wraparound cover as two-page spread. Editing credit as per entry for Batman DC, series Showcase Presents: Batman 6. DCSeries. Volume 6 Price All credits as per table of contents unless otherwise noted. View: Large Edit cover. Asylum of the Futurians! The House That Showcase Presents: Batman: Volume 6 Batman! Take-Over of Paradise! Man in the Eternal Mask! A Vow from the Grave! Blind Rage of the Ten-Eyed Man! Into Showcase Presents: Batman: Volume 6 Den of the Death-Dealers! Darrk death ; League of Assassins introduction? Reprints from Batman DC, series June Legacy of Hate! Freak-Out at Phantom Hollow! Editing E. Legend of the Key Hook Lighthouse! Striss does not know the deadly secret of the chemical formula. Reprints from Batman DC, series September Man-Bat Madness! Wail of the Ghost-Bride! Night of the Reaper! And Be a Villain! Secret of the Slaying Statues! Silent Night, Deadly Night! Reprints from Batman DC, series February Forecast for Tonight Vengeance for a Dead Man! Moon; Alfred Pennyworth; Mr. Reprints from Batman DC, series March Blind Justice Blind Fear! Highway to Nowhere! Bruce Wayne -- Rest in Peace! The Stage Is Set The Lazarus Pit! Reprints from Batman DC, series August Killer's Roulette! The Demon Lives Again! View Change Showcase Presents: Batman: Volume 6. -

Comic Books, Manga and Graphic Novels Spring, 2021 5 Credits Leonard Rifas (Pronounced "WRY-Fuss"; Call Me “Mr

HUM 270 SYLLABUS, Seattle Central College Comic Books, Manga and Graphic Novels Spring, 2021 5 credits Leonard Rifas (pronounced "WRY-fuss"; call me “Mr. Rifas” or “Leonard.”) Phone number: 206-985-9483 (home) I suggest that you confirm by email anything that you would like me to remember. Email: [email protected] Virtual office hours: Monday-Friday, 12:00-12:50, and by arrangement Text: Reading packet posted under “Files.” Course Description: In this class we will consider the history, achievements and problems of comic books, manga, and graphic novels. Comics, under one name or another, have been around for many years, but have achieved legitimacy relatively recently. We will study how they grew to become accepted and respected media. By considering examples from different times and places, we will have opportunities to learn how comics have functioned as part of global system of cultural power and influence. Creating and studying comics can contribute to the goals of the Humanities in several ways. These include by helping us to think more creatively and critically; to understand the world more widely and deeply; to communicate more clearly; and, by building empathy, to become more fully human. Course Student Learning Outcomes: Upon completion of the course, students will be able to: 1. explain how comics, manga and graphic novels have evolved, as formats, as industries, and as means of expression 2. describe the works of some cartoonists from various times and places 3. apply the basic principles of cartooning to create an original and understandable work in comics format 4. research a question related to sequential art (comic books, manga, or graphic novels) and present your findings Course Method: The methods most frequently used in this class will include the instructor’s illustrated lectures (recorded with Panopto); reading the assigned materials; writing assignments; and cartooning lessons.