That's Where the Money Is

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, a Public Reaction Study

Nebraska History posts materials online for your personal use. Please remember that the contents of Nebraska History are copyrighted by the Nebraska State Historical Society (except for materials credited to other institutions). The NSHS retains its copyrights even to materials it posts on the web. For permission to re-use materials or for photo ordering information, please see: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/magazine/permission.htm Nebraska State Historical Society members receive four issues of Nebraska History and four issues of Nebraska History News annually. For membership information, see: http://nebraskahistory.org/admin/members/index.htm Article Title: Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, A Public Reaction Study Full Citation: Randy Roberts, “Heavyweight Champion Jack Johnson: His Omaha Image, A Public Reaction Study,” Nebraska History 57 (1976): 226-241 URL of article: http://www.nebraskahistory.org/publish/publicat/history/full-text/NH1976 Jack_Johnson.pdf Date: 11/17/2010 Article Summary: Jack Johnson, the first black heavyweight boxing champion, played an important role in 20th century America, both as a sports figure and as a pawn in race relations. This article seeks to “correct” his popular image by presenting Omaha’s public response to his public and private life as reflected in the press. Cataloging Information: Names: Eldridge Cleaver, Muhammad Ali, Joe Louise, Adolph Hitler, Franklin D Roosevelt, Budd Schulberg, Jack Johnson, Stanley Ketchel, George Little, James Jeffries, Tex Rickard, John Lardner, William -

Predict Big Ten Willthrow out Freshman Rule J

February 18, EVENING TIMES <PHOSE CHERRY 8800) Thursday, 1943 PAGE 26 DETROIT Predict Big Ten WillThrow Out Freshman Rule j Sports NEED LOTS OF PEP' Sports 'OPEN WIDE, BIRDIES! YOU First Year Men SPORT 2d Detroit Girl, Mourns SHORTS At Manion, Keogan's Death, lo Get Chance Selfridge Field basketball Crashes Movies team marked up victory No. 16 in 22 games hy trimming East LEO MACDONELL During Side of Detroit, M-44 . “Ath- By Irish Cage Pilot 1943 letics as usual" is no longer possible at Harvard, Yale and t appcii- is thr CHICAGO, Feb. 18 fINSL— ‘ roller gj • ni movie SI.'L'TH BKNIX In 4 IVh Ik Princeton, a joint statement George* Western Conference universities r, r< rj‘ INS' The death of Dr. from the three presidents said. \V;ih Block now in keogan 52. Notre Dame will throw out the freshman rule Mclva basket-j ”, . we hope to continue some special meeting of IMA" V<l. \r i .Manion Miss ha . coach for 21 years, was in athletics at a rollej campu** such sports upon a restricted * top n\ al for skai* mourned on the university the athletic directors and faculty BUkA and informal basis, hut realize ir.i; honor s, is cxpo< ir<i To hr in ud in athletic circles throughout representatives in Chicago. Sun- •¦ I . this must depend on the , rrnvi- * ;»!>.’/»: in Aptio'li day, It was predicted today by, the forces 'T ; SkiUrJ v UiT;r» of 19177 today. plans of armed and w h Big officials. the ODT," they announced. w 1 -. -

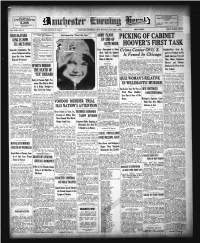

Picking of Cabinet Hoover' S First Task

--■W THB WBATHRR NET PRESS RUN ^ a r t m m t by U. *. WcbthM Bmean, AVERAGE DAILY CIRCULATION H««» Barca for the month of December, 1028 ^^,jC 0tD 9- •i’ . Fair and colder tonight and 5,209 C 0 9 » Tnes^day. Blember of the Andit Bnreaa ot ClrcnlatioBS (TEN PAGES) PRICE THREE CENTS VOL. x u n ., NO. 71. (Classified Advertising on Page 8) SOUTH MANCHESTER, CONN., MONDAY, JANUARY 7,1929. TEX MADE MILLIONS J U G m V lA N WITH HI^ ETGHTERS Kidnapped by “Kind Old Man” ARMY PLANE New YorK, Jan. 7.— Here are 4> some of the biggest fights pro PICKING OF CABINET KING IS NOW moted by Tex RicKard with the UP END OF gate receipts: 1927— Tunney-Dempsey, Chi cago, $2,650,000. m H O D R ITS DICTATOR 1926 — Tunney - Dempsey, HOOVER’S FIRST TASK Philadelphia, $1,985,723. •$> 1921 — Dempsey-Carpentler, $1,626,580. Suspends Consdtution, Dis- 1927— Dempsey-Sharkey, $1- Crew Determined to Keep President-Elect First Re 083,529. Crime Center O f U, S. 1923— Dempsey-FIrpo, $1,- Aloft Until the Engines ports to President on His solves Parliament and Ap 082,590. 1924— Wills-Firpo, $462,580. Is Found In Chicago points His Own Cabinet; 1919 — Dempsey - Willard, BreaK Down — Repairs South American Trip and $452,522. 1923— Firpo-WUlard, $434,- Made in Mide-Air. Chicago, Jan. 7.— Federal, coun-^and we expect to have them within Then Meets Delegates; Belgrade Overjoyed. • 269. ty and city forces prepared today to a short time,” declared First ^ ■ Assistant U. -

Sample Download

What they said about Thomas Myler’s previous books New York Fight Nights Thomas Myler has served up another collection of gripping boxing stories. The author packs such a punch with his masterful storytelling that you will feel you were ringside inhaling the sizzling atmosphere at each clash of the titans. A must for boxing fans. Ireland’s Own There are few more authoritative voices in boxing than Thomas Myler and this is another wonderfully evocative addition to his growing body of work. Irish Independent Another great book from the pen of the prolific Thomas Myler. RTE, Ireland’s national broadcaster The Mad and the Bad Another storytelling gem from Thomas Myler, pouring light into the shadows surrounding some of boxing’s most colourful characters. Irish Independent The best boxing book of the year from a top writer. Daily Mail Boxing’s Greatest Upsets: Fights That Shook The World A respected writer, Myler has compiled a worthy volume on the most sensational and talked-about upsets of the glove era, drawing on interviews, archive footage and worldwide contacts. Yorkshire Evening Post Fight fans will glory in this offbeat history of boxing’s biggest shocks, from Gentleman Jim’s knockout of John L. Sullivan in 1892 to the modern era. A must for your bookshelf. Hull Daily Mail Boxing’s Hall of Shame Boxing scribe Thomas Myler shares with the reader a ringside seat for the sport’s most controversial fights. It’s an engaging read, one that feeds our fascination with the darker side of the sport. Bert Sugar, US author and broadcaster Well written and thoroughly researched by one of the best boxing writers in these islands, Myler has a keen eye for the story behind the story. -

Come In-The Water's Fine

May 26, 1961 THE PHOENIX JEWISH NEWS Page 3 Final Scores JEWS IN SPORTS Boxing Story SPORT In Bowling HTie AfSinger BY HAROLD U. RIBALOW was the big night of Singer’s ca- reer. More than 35,000 fans crowd- SCOOP NEW YORK, (JTA)—The death ed into Yankee Stadium, paying By RONfclE PIES him in the 440. Throughout the of former lightweight the title fight be- gap. With 10 Announced last month $160,000 to see goal race Art closed the boxing champion A1 Singer was a tween Singer and the lightweight In keeping with the prime yards remaining, he passed his op- Final season scores in B'nai to all who follow the sport. champion, 26-year-old Sammy of this series, which is to give rec- ponent pulled away to win. blow the of Phoe- and B’rith bowling leagues have been Al Singer was known as a boxer Mandell. The champ was a ten- ognition to Jewish athletes TO COMPLETE his high school Singer nix and Arizona, we will honor a announced: with a “glass jaw.” This is an year veteran of the ring; career, Art was invited to a na- disease, which means three years of fighting different athlete in each article. tional championship meet in Los Majors league Carl Slonsky, occupational had only chosen that a man has a physical weak- behind him. The first person we have Angeles to compete with some of high individual series of 665; Jack the A shot at the jaw out cautiously, to honor is Art Gardenswartz, Uni- in the 269. -

The Daily Scoreboard

10 – THE DERRICK. / The News-Herald Tuesday, April 14, 2015 THE DAILY SCOREBOARD Major League Baseball standings PGA Tour leaders AMERICAN LEAGUE PGA Tour FedExCup Leaders Through April 12 East Division Rank Player Points YTD Money W L Pct GB WCGB L10 Str Home Away 1. Jordan Spieth 2,009 $4,958,196 Boston 5 2 .714 — — 5-2 W-1 1-0 4-2 2. Jimmy Walker 1,680 $3,509,349 Tampa Bay 4 3 .571 1 — 4-3 W-3 1-2 3-1 3. J.B. Holmes 1,233 $2,942,520 Toronto 4 3 .571 1 — 4-3 L-1 0-1 4-2 4. Patrick Reed 1,173 $2,344,556 Baltimore 3 4 .429 2 1 3-4 L-2 1-3 2-1 5. Bubba Watson 1,117 $2,720,950 New York 3 4 .429 2 1 3-4 W-2 2-4 1-0 6. Dustin Johnson 1,106 $2,991,117 Central Division 7. Charley Hoffman 1,031 $2,228,407 8. Ryan Moore 952 $2,171,580 W L Pct GB WCGB L10 Str Home Away 9. Jason Day 941 $2,047,528 Kansas City 7 0 1.000 — — 7-0 W-7 3-0 4-0 10. Hideki Matsuyama 939 $2,156,046 Detroit 6 1 .857 1 — 6-1 L-1 3-0 3-1 11. Robert Streb 903 $1,791,267 Chicago 2 4 .333 4½ 1½ 2-4 W-2 2-1 0-3 12. Sangmoon Bae 898 $1,917,411 Cleveland 2 4 .333 4½ 1½ 2-4 L-3 0-3 2-1 13. -

Download Chapter

PART III (Candidate Hoover's personal popularity was gaining such momen• tum that his recognition as the "people's choice" awaited only definite word from President Coolidge that he would not be a candidate. Defeat of the "Party Bosses" at the convention delighted Ding, for now Hoover could wage a campaign unrestricted by patronage promises. Wot/ember 22, 1927 D URING THE MONTHS before the 1928 con• vention, President Coolidge did not definitely clarify whether he would be a candidate, if drafted. As speculation continued, news• papers proclaimed: SET MAXIMUM TAX SLASH AT 250 MILLIONS TABER ELECTED TO HEAD GRANGE FOR 3RD TIME GORDON PLANS "SURPRISE" IN FALL- SINCLAIR JURY QUIZ ASK COOLIDGE TO INTERVENE IN COAL STRIKE KEARNS-DEMPSEY TRIAL ENDS IN NONSUIT [58] Something seems to be holding them back. 29, 1927 ]\1[ONTHS AHEAD of the convention, the political situation as to Herbert Hoover led the party leaders (Ding called them bosses) to try to steer the party's thinking away from Hoover. Meantime: U.S. PAYS TAX REBATES TO 240,000 read a headline; among the recipients were former President Taft, Harry Lauder, and Judge Kenesaw Mountain Landis. Mexi• can Senate started action on the law which eventually took over U. S.-owned oil wells. Colonel Charles Lindbergh was on a good• will trip to Central America. Attempt was being made to reach an agreement with President Coolidge on McNary-Haugen farm bill, which he vetoed. And REPORT GEHRIG WANTS $25,000 the sports pages said. [60] One of those party line calls. 22, 1928 JL HERE CAME the time, then, when Hoover was generally recognized as the leading candi• date for the nomination, but there were the usual "favorite sons" of several states who could be expected to have complimentary votes. -

Chesterfield Put This Down Ac, Has Remained America’S Fastest'growing Cigarette; Over Two Billion Are Smoked Per Month

1---N /---- hililren. The unpn>tt ,d niovii Yukon Dell Yt. r.lierjfr, Alaska’s Tuner; irojector was in tin- middle of Hi* Hospital Ship now in .Juneau Phono .Juneau Music 49 ARE KILLED mil with inflanmiahU Him in uric Ready to Be Laid Up House or Hote l (last menu. —atlv. ) FAMOUS BATTLES ill a table. A caudle was hurtling ♦ ♦ ♦ WE WANT YOU TO KNOW I mil two lllms cauclil !:r< limn il TANW'A. Alaska, Sept. 7 Use the Classifieds. They pay. THAT WE SELL AND THEATRE FIRE rhere was a stillm then l In pn\eminent hospital lmat iMartlia \n for the :: ———-?!;:I trowd rushed fur llic ime dim ip line lias arrived here and wii INSTALL await orders ns to whether ii wii I I UMKRK’K, Ireland. Sept. 7- Forty ■ eo into winter hero or HEAVYWEIGHT TITLE nine prisons are reported to have quarters make other trips hefore the rive, ARCOLA -O- been killed and 10 injured in a fire in an movie theater. An SCHEDULE*FOR freeze-up. improvised By The Associated Press HEATING SYSTEMS unscreened projecting a p p a r a Mi s caught afire. One door, the onh Hauled exit, became jammed and many per- COAST LEAGUE (Garbage by J. J. WOODARD CO. Jim Jefferies knocked out Hob die (iraney, the referee, was all j sons were trampled to death and Month or Plumbing—Sheet Metal Work Fitzsimmons July 25, 11102, in the dressed up in the "conventional Opening Ibis afternoon, the clubs Trip j burned. Twenty nine bodies recov- General ; South Front Street eighth round of a bout in a vacant evening dress." if the Pacific Coast League will Contracting, Concrete ered are unrecognizable. -

Senate Resolution No. 1653 Senator TEDISCO BY: Billy Petrolle Posthumously Upon the HONORING Occasion of Being Inducted I

Senate Resolution No. 1653 BY: Senator TEDISCO HONORING Billy Petrolle posthumously upon the occasion of being inducted into the Schenectady School District Athletic Hall of Fame WHEREAS, It is the sense of this Legislative Body to pay tribute to outstanding athletes who have distinguished themselves through their exceptional performance, attaining unprecedented success and the highest level of personal achievement; and WHEREAS, Attendant to such concern and in full accord with its long-standing traditions, this Legislative Body is justly proud to honor Billy Petrolle posthumously upon the occasion of being inducted into the Schenectady School District Athletic Hall of Fame on Monday, September 16, 2019, at Glen Sanders Mansion, Scotia, New York; and WHEREAS, Billy Petrolle was raised in Schenectady, New York, where he attended public school and started boxing as an amateur at just 15 years old; and WHEREAS, Known as Fargo Express, Billy Petrolle began his illustrious pro boxing career in 1922; once rated as the top challenger for the welterweight, junior-welterweight and lightweight titles, he fought for the World Lightweight Title on November 4, 1932, at Madison Square Garden; and WHEREAS, With other notable fights against Barney Ross and Kid Berg, Billy Petrolle knocked out Battling Battalino in front of 18,000 fans at Madison Square Garden on March 24, 1932, and defeated Jimmy McLarnin at MSG on November 21, 1930; and WHEREAS, Participating in ten current or past World Championships, Billy Petrolle won five of them; in addition to -

Ing the Needs O/ the 960.05 Music & Record Jl -1Yz Gî01axiï0h Industry Oair 13Sní1s CIL7.: D102 S3lbs C,Ft1io$ K.'J O-Z- I

Dedicated To Serving The Needs O/ The 960.05 Music & Record jl -1yZ GÎ01Axiï0H Industry OAIr 13SNí1S CIL7.: d102 S3lbS C,ft1iO$ k.'J o-z- I August 23, 1969 60c In the opinion of the editors, this week the following records are the SINGLE 1'1('It-.%" OE 111/î 11'1î1îA MY BALLOON'S GOING UP (AssortedBMI), 411) Atlantic WHO 2336 ARCHIE BELL AND WE CAN MAKE IT THE DRELLS IN THE RAY CHARLES The Isley Brotiers do more Dorothy Morrison, who led Archie Bell and the Drells Ray Charles should stride of their commercial thing the shouting on "0h Happy will watch "My Balloon's back to chart heights with on "Black Berries Part I" Day," steps out on her Going Up" (Assorted, BMI) Jimmy Lewis' "We Can (Triple 3, BMI) and will own with "All God's Chil- go right up the chart. A Make It" (Tangerine -blew, WORLD pick the coin well (T Neck dren Got (East Soul" -Mem- dancing entry for the fans BMI), a Tangerine produc- 906). phis, BMI) (Elektra 45671). (Atlantic 2663). tion (ABC 11239). PHA'S' 111' THE U lî lî /í The Hardy Boys, who will The Glass House is the Up 'n Adam found that it Wind, a new group with a he supplying the singing first group from Holland - was time to get it together. Wind is a new group with a for TV's animated Hardy Dozier - Holland's Invictus They do with "Time to Get Believe" (Peanut Butter, Boys, sing "Love and Let label. "Crumbs Off the It Together" (Peanut But- BMI), and they'll make it Love" (Fox Fanfare, BMI) Table" (Gold Forever, BMI( ter, BMI(, a together hit way up the list on the new (RCA 74-0228). -

Tony Canzoneri, Underdog, Attempts to Defeat Mandell Tonight

THE BISMARCK TRIBUNE. FRIDAY, AUGUST 2, 1929 \ ¦¦ Tony Canzoneri, Underdog, Attempts to Defeat Mandell Tonight < UGHTWEIGHT CHAMP CANTWELL ALLOWS ONLYTHREE HITS BUT CUBS DEFEAT BRAVES TO RECEIVE {56,000 Canzoneri in Training Rates as Rassling Queen Cohen Has Friends I li PITTSBURGH PIRATES •*• * * * INDEPENDINGCROWN Oregon Woman, Married to One, Manages Him and From 27 Nations Promotes Matches SNAP OUT OF SLUMP Kansas City. Aug. 2—(*»)—Wilbur P. “Junior” Coen is convinced that a 25,000 Fans to Watch Ten- European tour la broadening in more ways than one. even for a tennis star Round Duel Between Clever AND NOSE OUT PHILS The 17-year-old Kansas City net ace modestly mentioned that he made personal friends with court repre- Boxer and Slugger Boston Club Outhits Chicago, sentatives of 27 nations during his recent tour abroad. He played in ex- Bush Gets Cedit hibition and tournaments in 13 coun- BOTH FIGHTERS CONFIDENT but for tries. Coen tfans another European jaunt 1 to 0 Victory next winter to gain a second leg on the famous Macomber cup, to further Sammy Says Challenger Will aspirations to gain permanent pos- Bother Him No More Than AND session of it by winning it three times. BENTON ALEXANDER WIN Coen won this year by defeating Maer McGraw or McLarnin of the Spanish Davis cup team. Athletics Add Game to Lead as Chicago, Aug. 2—i/Tt—Sammy Mandril is expected to receive Yankees’ Two Home Runs Alabama Plans $38,000 fer defending his light• weight crown against Tony Can- Are Not Enough zoneri tonight. Both are signed Deep Sea Rodeo on a percentage basis, Sammy to gei 40 per and Tony 20 per By W. -

Prepared to Settle Dispute in Bolivia

^‘■-- '!•,,* • •■•. -'• ■ ■ ; ' ■"" V V ' ■*' •■■ .'■ •'■ “ •• ■ ‘•• i -iA -•'•- ■ •: - . '^ .* ■•'' ^ . : . «• ■■ . ^ ^ . .-» ■■■ C ' 'J / ' »• V ’ »**i' •'• ' * . ' ’ . • ■• . , . vj: . w a • N 'I ' '-"■T INET PRESS RUN ' THE WITHER >, F erocast b j I), 8. .tnteathei! BaK'8M« AVERAGE DAILY CIRCULATION New H arcB . „ for the month of November, lOiiS Rain tonight and Friday; some 5,237 what colder Friday. Member of the Aadlt Bnrean of . \ cotv^-' Clrcnlatlona joaio*’ ' t PRICE THREE CENTS VOL. XLIIL, NO. 57. (Classified Advertising on Page 10> SOUTH MBANCHESTEB, C0NN.^ THURSDAY, DECEMBER 20, 1928. (EIGHTEEN PAGES) Pennsy Infant Dies Mark Aviation’s Birthplace . reOLlEY HTIS KELLOGG P A Q i- PREPARED TO SETTLE AirrO; STARTS Victim O f Witchcraft HELD BACK BY * <} % DISPUTE IN BOLIVIA y J s C i r a SERIES Lebanon, Pa., Dec. 20.— The have called in a "pow-wow” doc BIG N M BILL attention of authorities today was tor. * Pan-American Conference- focused anew on the “ pow-wow- After several visits of the witch doctor who was said to reside at .A AFGHANISTAN Love Lane Accident Finally iug” activities of individuals in Hamlin, Yerks county, the child Opponents Say They W3I south-central Pennsylvania when failed to rally and died. Coroner J. > Lays Ground Work for an an infant, said to have been a vic H. Manbeck, of Lebanon county, Affects Two Other Trol- tim of witchcraft, was found dead said the child succumbed to mal Start Filibuster Until the CAPITAL HED Arbitration Treaty Be i of malnutrition. nutrition. The child, Verliug Davis, son of Manbeck said that apparently leys and Autos and a Mo- Verna Davis of Fredericksburg, the child had not suffered from the Senate Takes Its Christ BY THE KING tween South American Re had been ill for some time and aft treatment administer by the “ pow- er a regular physician , had been Avow” doctor, but that death was mas Recess Saturday.