Irina Baydarova Thesis

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

MERGED LIST from Scival and Incites Names Arranged

T1ABLE 24.3 - MERGED LIST FROM SCiVAL and InCites Names arranged alphabetically by MQA Registry SV=SciVal; IC is InCItes PUBLICATION RANKINGS SETARA TYPE 1 INSTITUTION SOURCE SV IC Tier Abbreviation Asia Metropolitan U was Master kill 2 College of Nursing & Health SV 67 Universiti Multimedia or University 2 Multimedia B 13 12 T 5 MMU AIMST-Asian Institute of Medicine, 2 Science & Technology B 39 36 T 4 Asia Pacific University of Technology and 2 Innovation SV 42 T 5 AP UTI Binary University of Management & 2 Entrepreneurship SV 63 BUCME 2 Curtin University , Sarawak MY IC 34 T 5 CMYS Cyberjaya University College of Medical 2UC Sciences SV 47 T 5 CSM GOV Forest Research Centre - Sandakan SV 46 FRC Forest Research Institute Malaysia (Inst GOV Penyelidikan Perhutanan) B 33 29 FRIM 2 Help University IC 41 T 4 2UC Heriot-Watt University Malaysia SV 60 HWUM GOV Hospital Pulau Pinang SV 44 Institute for Medical Research (Institut GOV Penyelidikan Perubatan) B NOTE 2 31 23 Institute Jantung Negara (Ntl Heart Inst. Corp with IJN College) IC 46 IJN Institute Penyelidikan Getah MY (part of GOV MY Rubber Board) IC 45 International Islamic University MY (Uni 1 Islam Antarabangsa ) B 7 9 T 5 IIUM 2 International Medical University B 21 22 T 5 IUM 2 INTI International University SV 41 T 5 INTIUI GOV Jabatan Hutan Sarawak (Forest Dep) IC 48 2UC KDU University College SV 66 KDUJP Kementerian Kesihatan Malaysia GOV (Ministry of Health) B 34 33 2 C Kolej Teknologi Pulau(Island College) SV 64 MY 5 KCI 2UC Kolej Universiti Poly-Tech MARA SV 62 MY 4 KUPTM GOV -

Garis Panduan Permohonan Application Guideline

APPLICATION GUIDELINE/REQUIREMENT GARIS PANDUAN PERMOHONAN TERTIARY EDUCATION SPONSORSHIP PROGRAMME (TESP 2020) Open to all full-time student who are currently pursuing First Degree Programme at selected field and selected Local Higher Learning Institution. APPLICATIONS REQUIREMENTS • Application must be made online thru MARA Portal via: www.mara.gov.my starting 13th April 2020 (Monday) 10.00am until 4th May 2020 (Monday) 12.00pm. • Applicant must meet the general requirements and academic requirements. • If false information given by the applicant, MARA reserves the right to terminate or withdraw the loan offer. GENERAL REQUIREMENTS • Malaysian. • Applicant and either one parents is Bumipuera. • Meet the family Sosio Economy Status (SES) eligibility requirements set by MARA. • Parents total taxable income is not more than RM180,000 a year. If parents are self- employed or work at oversea, their average gross income must be less than RM 15,000 per month • Parents/Guardians and applicant are not blacklisted by MARA. • Applicant do not receive any financial support/sponsorship from any agency for current study programme (double sponsor). • Sponsorship is not given to applicant taking same programme level. • Free from any chronic/ contagious disease/ disease that require follow-up treatment. • Applicant age limit should not exceed 40 years old at the time of application. ACADEMIC REQUIREMENTS New Student • Obtain CGPA > 3.0 in Asasi/ Matriculation/ Persediaan/ STPM and equivalent. Existing Student • Obtain CGPA > 3.0 in previous semester; AND • Their balance study is not less than a year. Others • Pass SPM with credit Bahasa Melayu. • Academic requirement for medicine, dentistry and pharmacy programme must be meet the criteria set by professional board. -

(Grep) 2020 APPLICATION GUIDELINES

GRADUATE EXCELLENCE PROGRAMME (GrEP) 2020 APPLICATION GUIDELINES 1.0 INTRODUCTION MARA offers educational loans in the form of convertible loans to Post-Graduate (Masters and Doctor of Philosophy) degrees at top ranking LOCAL universities to outstanding graduates in the fields that meet the need of the nation’s workforce demand. 2.0 TERMS OF APPLICATION The general and specific terms for applications are as follows: 2.1 General Terms 2.1.1 The applicant and either parent are Bumiputera and Malaysian. 2.1.2 Applicant's age limit as of 31 December 2020: Level of study Maximum Age limit Master 40 years Doctor of Philosophy 45 years 2.1.3 Applicants have completed their Undergraduate / Master's degree with outstanding achievement as described in paragraph 2.2.1. 1 2.1.4 Applicants must be certified to be of good health by a registered medical practitioner and free from pregnancy, mental illness, physical disability, infectious diseases (HIV-AIDS, Hepatitis B & C and others), epilepsy, genetic diseases and drug abuse. 2.1.5 The applicant / mother / father / guardian is not blacklisted under legal action by MARA. 2.1.6 Applicants are not under any financial or sponsorship contract with any other agency at the time of application. 2.1.7 Applicants must obtain a release / suspension of service contract or repayment of loan from other sponsorship body. Employed applicants need to obtain an unpaid study leave or a formal confirmation of their resignation from their employer. 2.1.8 Applicants have never been under termination or disciplinary action by any sponsorship body education institutions. -

Science Fund Guidelines

MINISTRY OF SCIENCE, TECHNOLOGY AND INNOVATION, MALAYSIA SCIENCEFUND GUIDELINES FOR APPLICANTS Fund Secretariat Planning Division Ministry of Science, Technology and Innovation Level 3, Block C5, Parcel C Federal Government Administrative Centre 62662 Putrajaya. Tel: 603 – 8885 8842 / 8852 / 8145 / 8758 / 8778 Fax: 603 – 88892994 http://ernd.mosti.gov.my/eScience Table of Contents Page Chapter 1: Introduction to ScienceFund 1.1 Definition Of ScienceFund 1 1.2 Objectives Of ScienceFund 1 1.3 Research Cluster (RC) And Priority Areas 1 1.4 Eligibility Criteria 1 1.5 Selection Criteria Of The Project 2 1.6 Location Of Research 2 1.7 Project Duration 2 1.8 Responsibility Of The Project Leader 3 1.9 Scope Of Funding 3 1.10 Variation In Project Costing 5 1.11 Non-Qualifying Project Activities 5 1.12 Project Extension 5 1.13 Notification Of Results 5 1.14 Acceptance Of Offer 6 1.15 ScienceFund Agreement 6 1.16 Ownership And Use Of R&D Equipment 6 1.17 Intellectual Property Rights 6 1.18 Publications 6 1.19 Monthly Financial Report 7 1.20 Change Of Project Leader 7 1.21 Transfers Of Grants Between Organisations 7 1.22 Termination 7 Chapter 2: Project Application 2.1 Application Process 8 2.2 Application Submission 8 2.3 Application Form 8 Chapter 3: Project Evaluation 3.1 Institutional Screening Committee 15 3.2 Technical And Financial Evaluation Committee At MOSTI 15 3.3 Fund Approval Committee 15 Chapter 4: Allocation and Disbursement of Fund 4.1 Quantum Of Funding 16 4.2 Initial Disbursement 16 4.3 Progress Payment 16 4.4 Institutional Financial -

Garis Panduan Permohonan

GARIS PANDUAN PERMOHONAN PROGRAM PENAJAAN PENGAJIAN TERTIARI (TESP 2021) TERTIARY EDUCATION SPONSORSHIP PROGRAMME (TESP) Terbuka kepada pelajar yang sedang mengikuti pengajian secara sepenuh masa peringkat Ijazah Pertama dalam bidang tertentu di Institut Pengajian Tinggi (IPT) terpilih di dalam negara. MAKLUMAT PERMOHONAN • Permohonan hendaklah dibuat secara atas talian di Portal MARA melalui pautan: www.mara.gov.my bermula 01 Mac 2021 (Isnin) hingga 19 Mac 2021 (Jumaat). • Pemohon perlu memenuhi syarat-syarat umum dan syarat akademik yang telah ditetapkan. • Sekiranya pemohon didapati memberi maklumat palsu, MARA berhak pada bila-bila masa menamatkan atau menarik balik tawaran pinjaman. SYARAT UMUM • Warganegara Malaysia. • Pemohon serta salah seorang ibu atau bapa bertaraf Bumiputera • Memenuhi syarat kelayakan Status Sosio-Ekonomi (SES) keluarga seperti berikut: Pendapatan Bercukai Kategori Kelayakan Pendapatan Bulanan Tahunan Yuran & Elaun Sara Hidup RM12,000 dan ke bawah RM150,000 dan ke bawah Yuran sahaja RM12,001 - RM20,000 RM150,001 – RM250,000 • Ibu dan bapa/penjaga serta pelajar tidak disenaraihitam oleh MARA. • Tidak pernah menerima pinjaman MARA bagi peringkat pengajian yang sama. • Bebas daripada penyakit kronik / berjangkit / penyakit yang memerlukan rawatan susulan. • Had umur pemohon adalah tidak melebihi 40 tahun semasa permohonan dibuat. SYARAT AKADEMIK Pelajar Baharu • Mendapat CGPA > 3.00 di peringkat Asasi / Matrikulasi / Persediaan / STPM serta setaraf; • Telah mendapat tawaran/mendaftar di IPT bermula Januari 2021. Pelajar Sedia Ada • Mendapat CGPA > 3.00 bagi semester terdahulu; DAN • Mempunyai baki tempoh pengajian tidak kurang dari satu (1) tahun. 1 Lain-Lain Syarat • Lulus dengan kepujian dalam subjek Bahasa Melayu di peringkat SPM. • Kelayakan akademik bagi program Perubatan, Pergigian dan Farmasi mestilah memenuhi kriteria yang ditetapkan oleh Badan-Badan Profesional. -

Tesp 13 Ogos 2020

KEMENTERIAN PEMBANGUNAN LUAR BANDAR Terbuka kepada pelajar yang sedang mengikuti pengajian secara sepenuh masa peringkat Ijazah Pertama dalam bidang tertentu di Institut Pengajian Tinggi terpilih. Permohonan Secara Atas Talian Sila layari http://www.mara.gov.my Bahagian Penganjuran Pelajaran, Tingkat 10, Ibu Pejabat MARA 21 Jalan MARA, 50609 Kuala Lumpur MAKLUMAT PERMOHONAN Permohonan hendaklah dibuat secara atas talian di Portal MARA melalui pautan: www.mara.gov.my 27 Ogos 2020 (Khamis) pukul 10.00 pagi sehingga 13 November 2020 (Jumaat) pukul 4 petang. Pemohon perlu memenuhi syarat-syarat umum dan syarat akademik yang ditetapkan. Sekiranya pemohon didapati memberi maklumat palsu, MARA berhak pada bila-bila masa menamatkan atau menarik balik tawaran pinjaman. 03-2613 2051 / 2024 / 2518 / 2059 / 2100 / 2069 / 2070 [email protected] majlisamanahrakyat majlisamanahrakyat maragov PROGRAM PINJAMAN PELAJARAN TERTIARI (TESP 2020) ENGINEERING & ENVIRONMENT MARKETING, BUSINESS & • Chemical Engineering MANAGEMENT • Civil Engineering BUILD PROFESSIONALS • Mechanical • Electrical Electronic • Architecture • Robotics & Automation • Interior Architecture • Marketing Management • Telecommunication • E-business • Interior Design Engineering • Quantity Surveying • International Business Mgt • Mechatronic • Economics • Nanotechnology • Logistics Management • Petroleum Engineering • Supply Chain Management • Solar Energy • On Line Sales & Supply • Wind Energy • Marketing Communications • Environmental Engineering ACCOUNTING & FINANCE • Law • Occupational -

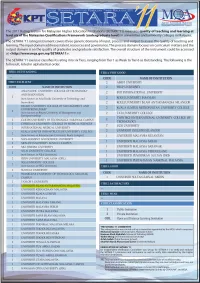

SETARA '11 ADVERTORIAL BI-V2.Pdf

KPrK ..MlrNTIERIAN PI:HCAJIAN TINCCI The 2011 Rating ystem for Malaysian Higher Education Institutions (SETARA '11) measures ~uality of teaching and learning at level six....of t e Malaysian Qualifications Framework (undergraduate level) in universities and university colleges in Malaysia. ne SETARA '11 rating instrument covers three generic domains of input, process and output to assess the quality of teaching and learning. The input domain addresses talent, resources and governance. The process domain focuses on curriculum matters and the output domain is on the quality of graduates and graduate satisfaction. The overall structure of the instrument could be accessed at <http://www.mqa.gov.my/SETARA11 >. The SETARA '11 exercise classifies its rating into six Tiers, ranging from Tier 1 as Weak to Tier 6 as Outstanding. The following is the full result, listed in alphabetical order: TIER6: OUTSTANDING TIER 4: VERY GOOD CODE NAME OF INSTITUTION TIER 5: EXCELLENT 2 AIMST UNIVERSITY CODE NAME OF INSTITUTION 2 HELP UNIVERSITY ASIA PACIFIC UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF TECHNOLOGY 2 INTI INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY AND INNOVATION 2 (now known as Asia Pacific University of Technology and 2 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI INSANIAH Innovation) 2 KOLEJ UNIVERSITI ISLAM ANTARABANGSA SELANGOR BINARY UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF MANAGEMENT AND 2 KUALA LUMPUR METROPOLITAN UNNERSITY COLLEGE ENTREPRENEURSHIP 2 (now known as Binary University of Management and 2 TATi UNIVERSITY COLLEGE Entrepreneurship) TWINTECH INTERNATIONAL UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF CURTIN UNIVERSITY OF TECHNOLOGY SARAWAK -

Garis Panduan Permohonan

GARIS PANDUAN PERMOHONAN PROGRAM GRADUAN CEMERLANG 2021 GRADUATE EXCELLENCE PROGRAMME (GrEP) 2021 1.0 PENGENALAN MARA menawarkan pinjaman pelajaran dalam bentuk pinjaman boleh ubah ke peringkat Pasca Siswazah (Sarjana dan Doktor Falsafah) di Institusi Pengajian Tinggi terkemuka dalam dan luar negara kepada graduan cemerlang dalam bidang yang memberi impak besar kepada keperluan guna tenaga negara. 2.0 SYARAT KELAYAKAN PERMOHONAN Calon-calon mestilah memenuhi syarat umum dan syarat khusus permohonan seperti berikut: 2.1 Syarat Umum 2.1.1 Pemohon dan salah seorang ibu ATAU bapa adalah berketurunan Bumiputera dan warganegara Malaysia. 2.1.2 Had umur pemohon pada 31 Disember 2021: Peringkat Pengajian Tempat Had Umur Pengajian Sarjana Dalam Negara Tidak melebihi 40 tahun Luar Negara Tidak melebihi 35 tahun Doktor Falsafah Dalam Negara Tidak melebihi 45 tahun Luar Negara Tidak melebihi 40 tahun 1 2.1.3 Pemohon telah menamatkan pengajian di peringkat Ijazah Pertama/Sarjana dengan kejayaan akademik cemerlang seperti yang dinyatakan dalam para 2.2.1. 2.1.4 Pemohon wajib disahkan mempunyai kesihatan yang baik oleh seorang pengamal perubatan berdaftar serta bebas dari mengandung, penyakit mental, cacat fizikal, penyakit berjangkit (HIV-AIDS, Hepatitis B & C dan lain-lain), epilepsi, penyakit genetik dan penyalahgunaan dadah. 2.1.5 Pemohon/Ibu/Bapa/Penjaga tidak termasuk dalam Senarai Hitam (blacklisted) MARA atau dalam tindakan Undang-Undang MARA. 2.1.6 Tidak mendapat bantuan kewangan/tajaan daripada mana-mana agensi bagi pengajian di peringkat yang sama. 2.1.7 Mendapat pelepasan/penangguhan kontrak perkhidmatan atau bayaran balik pinjaman daripada badan penaja lain. Bagi calon yang sedang dalam perkhidmatan perlu mendapat kelulusan cuti belajar atau pengesahan bertulis daripada majikan. -

List of Degree Granting Institutions in Malaysia As of 1 February 2017

LIST OF DEGREE GRANTING INSTITUTIONS IN MALAYSIA AS OF 1 FEBRUARY 2017 PUBLIC UNIVERSITIES NO. NAME REGISTERED IN MQR NOTES 1. International Islamic University Malaysia 2. Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia 3. University of Malaya 4. Universiti Malaysia Kelantan 5. Universiti Malaysia Pahang 6. Universiti Malaysia Perlis 7. Universiti Malaysia Sabah 8. Universiti Malaysia Sarawak 9. Universiti Malaysia Terengganu 10. Sultan Idris Education University 11. Universiti Pertahanan Nasional Malaysia 12. Universiti Putra Malaysia 13. Universiti Sains Islam Malaysia 14. Universiti Sultan Zainal Abidin 15. Universiti Sains Malaysia 16. Universiti Teknikal Malaysia Melaka 17. Universiti Teknologi Malaysia 18. Universiti Teknologi MARA 19. Universiti Tun Hussein Onn Malaysia 20. Universiti Utara Malaysia 1 | L i s t o f D e g r e e G r a n t i n g I n s t i t u t i o n s M a l a y s i a LIST OF DEGREE GRANTING INSTITUTIONS IN MALAYSIA AS OF 1 FEBRUARY 2017 PRIVATE UNIVERSITIES NO. NAME REGISTERED IN MQR NOTES 21. AIMST University Closed operation 15 August 2016. It is proposed that this institution to be 22. Albukhary International University remained in the list for another one year for public reference 23. Al-Madinah International University 24. Asia Metropolitan University Asia Pacific University of Technology and 25. Innovation Binary University of Management and 26. Entrepreneurship The institution is yet to submit application to City University College of Science and change its new name in the MQR 27. Technology Current name: City University DRB-HICOM University of Automotive 28. Malaysia 29. GlobalNxt University 30. -

PROGRAM GRADUAN CEMERLANG (Grep 2021)

KEMENTERIAN PEMBANGUNAN LUAR BANDAR PROGRAM GRADUAN CEMERLANG (GrEP 2021) PELAJAR CEMERLANG LEPASAN IJAZAH PERTAMA/SARJANA BAGI PENGAJIAN KE PERINGKAT SARJANA/DOKTOR FALSAFAH Permohonan Secara Atas Talian Sila layari http://www.mara.gov.my Bahagian Penganjuran Pelajaran, Tingkat 10, Ibu Pejabat MARA, 21 Jalan MARA, 50609 Kuala Lumpur majlisamanahrakyat majlisamanahrakyat maragov PROGRAM GRADUAN CEMERLANG 2021 PERMOHONAN Permohonan perlu dibuat secara atas talian (online) Permohonan yang tidak mendapat maklum balas dengan melayari laman web rasmi MARA daripada pihak MARA selepas tiga (3) bulan http://www.mara.gov.my mulai 01 Mac sehingga 19 daripada tarikh iklan adalah dianggap tidak berjaya Mac 2021. dan keputusan adalah muktamad. BIDANG PENGAJIAN ENGINEERING & ENVIRONMENT Chemical Engineering Civil Engineering Mechanical MARKETING,BUSINESS TRANSPORT Electrical Electronic & MANAGEMENT Motorcycle/Automotive Robotics & Automation Marketing Management Advertising & Brand Mgt / Heavy Vehicles/Trains/ Telecommunication Engineering E-business Film, TV, Video Broadcasting Aircraft/ Marine Mechatronic International Business Mgt Public Relation Motorcycle/Auto Design Nanotechnology Economics Phsycology Safety Petroleum Engineering Logistics Management Islamic Study/Syariah Emissions Solar Energy Supply Chain Management Electric Wind Energy On Line Sales & Supply Noise,vibration,harshness Environmental Engineering Marketing Communications Vehicle Electronics Occupational Safety and Health Law Durability Sales Material Business Management Parts -

(Jpa) Program Khas Lepasan Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia Dalam Negara Tahun 2021

TAWARAN PENAJAAN JABATAN PERKHIDMATAN AWAM (JPA) PROGRAM KHAS LEPASAN SIJIL PELAJARAN MALAYSIA DALAM NEGARA TAHUN 2021 1. PENGENALAN Permohonan adalah dipelawa kepada pelajar cemerlang lepasan Sijil Pelajaran Malaysia (SPM) 2020 yang mendapat keputusan sekurang-kurangnya 9A+ untuk melanjutkan pelajaran di dalam negara. Calon-calon akan ditawarkan penajaan untuk mengikuti pengajian peringkat Persediaan hingga ke Ijazah Pertama di Universiti Awam (UA), Government Linked Universities (GLU) dan Institusi Pengajian Tinggi Swasta (IPTS) dalam negara yang dikenalpasti, tertakluk kepada syarat-syarat yang ditetapkan. Penajaan Jabatan Perkhidmatan Awam (JPA) dalam bentuk Pinjaman Boleh Ubah (PBU). 2. PENAJAAN MENGIKUT PERINGKAT PENGAJIAN 2.1. Penajaan di bawah Program Khas Lepasan SPM Dalam Negara (LSPM) ini adalah secara berpakej merangkumi peringkat Persediaan dan Ijazah Pertama. 2.2. Pemohon tidak dibenarkan untuk mengikuti program persediaan dengan pembiayaan sendiri. Sekiranya berbuat demikian, pemohon tidak akan ditawarkan penajaan di peringkat Ijazah Pertama di bawah program ini. 2.3. Sekiranya pelajar enggan meneruskan penajaan di peringkat Ijazah Pertama di bawah tajaan JPA atau enggan mematuhi syarat-syarat penajaan yang ditetapkan oleh JPA bagi menyambung pengajian ke peringkat Ijazah Pertama, penajaan pelajar akan ditamatkan dengan tuntutan ganti rugi. 2.4. Calon-calon yang berjaya akan mengikuti program persediaan di kolej persediaan dalam negara yang telah ditetapkan oleh Kerajaan. Senarai program persediaan adalah seperti di LAMPIRAN A. 2.5. Seterusnya, penajaan peringkat Ijazah Pertama adalah di Institusi Pengajian Tinggi (IPT) dalam negara sahaja tertakluk kepada pelajar melepasi Had Kecemerlangan Akademik (HKA) di Peringkat Persediaan. Senarai IPT dalam negara adalah seperti di LAMPIRAN B. 2.6. Sekiranya pelajar yang ditaja tidak menamatkan kursus persediaan atau menamatkan kursus persediaan tetapi gagal melepasi HKA yang ditetapkan untuk melanjutkan pengajian ke peringkat Ijazah Pertama, penajaan pelajar boleh ditamatkan. -

Carta Liga Test Run.Xlsx

Team University Robot Check 1st Test-run Time 2nd Test-run Time A1 UM 8:45 9:00 - 9:10 9:10 - 9:20 A2 UTHM (PAGOH) 8:55 9:10 - 9:20 9:20 - 9:30 A3 UTHM (BATU PAHAT) B 9:05 9:20 - 9:30 9:30 - 9:40 A4 APU 9:15 9:30 - 9:40 9:40 - 9:50 A5 USM 9:25 9:40 - 9:50 9:50 - 10:00 B1 PSA 9:35 9:50 - 10:00 10:00 - 10:10 B2 IIUM A 9:45 10:00 - 10:10 10:10 - 10:20 B3 KKKB 9:55 10:10 - 10:20 10:20 - 10:30 B4 UMS 10:05 10:20 - 10:30 10:30 - 10:40 B5 MMU (MELAKA) 10:15 10:30 - 10:40 10:40 -10:50 C1 UNIMAP 10:25 10:40 -10:50 10:50 - 11:00 C2 UITM (SHAH ALAM) 10:35 10:50 - 11:00 11:00 - 11:10 C3 UTM B 10:45 11:00 - 11:10 11:10 - 11:20 C4 PPD 10:55 11:10 - 11:20 11:20 - 11:30 C5 PMJ 11:05 11:20 - 11:30 11:30 - 11:40 D1 UTAR 11:15 11:30 - 11:40 11:40 - 11:50 D2 SUNWAY UNI 11:25 11:40 - 11:50 11:50 - 12:00 D3 ILP MERSING 11:35 11:50 - 12:00 12:00 - 12:10 D4 TATIUC 11:45 12:00 - 12:10 12:10 - 12:20 D5 UKM 11:55 12:10 - 12:20 12:20 - 12:30 E1 ADTEC (KULIM) A 12:05 12:20 - 12:30 12:30 - 12:40 E2 MMU (CYBERJAYA) 12:15 12:30 - 12:40 12:40 - 12:50 E3 UITM (PASIR GUDANG) 12:25 12:40 - 12:50 12:50 - 13:00 E4 SEGI UNI 13:45 14:00 - 14:10 14:10 - 14:20 E5 TARC 13:55 14:10 - 14:20 14:20 - 14:30 F1 IIUM B 14:05 14:20 - 14:30 14:30 - 14:40 F2 ADTEC (KULIM) B 14:15 14:30 - 14:40 14:40 - 14:50 F3 UTEM 14:25 14:40 - 14:50 14:50 - 15:00 F4 UMPBOT 14:35 14:50 - 15:00 15:00 - 15:10 F5 UOW 14:45 15:00 - 15:10 15:10 - 15:20 G1 UTM A 14:55 15:10 - 15:20 15:20 - 15:30 G2 ILKBS 15:05 15:20 - 15:30 15:30 - 15:40 G3 MONASH UNI 15:15 15:30 - 15:40 15:40 - 15:50 G4 UPNM 15:25 15:40 - 15:50 15:50 - 16:00 G5 UMT 15:35 15:50 - 16:00 16:00 - 16:10 H1 UITM (PULAU PINANG) 15:45 16:00 - 16:10 16:10 - 16:20 H2 UNITEN 15:55 16:10 - 16:20 16:20 - 16:30 H3 MIU 16:05 16:20 - 16:30 16:30 - 16:40 H4 UTHM (BATU PAHAT) A 16:15 16:30 - 16:40 16:40 - 16:50 Pit No.