Unknown Kent by the Same Author

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Flash Flood History Southeast and Coast Date and Sources

Flash flood history Southeast and coast Hydrometric Rivers Tributaries Towns and Cities area 40 Cray Darent Medway Eden, Teise, Beult, Bourne Stour Gt Stour, Little Stour Rother Dudwell 41 Cuckmere Ouse Berern Stream, Uck, Shell Brook Adur Rother Arun, Kird, Lod Lavant Ems 42 Meon, Hamble Itchen Arle Test Dever, Anton, Wallop Brook, Blackwater Lymington 101 Median Yar Date and Rainfall Description sources Sept 1271 <Canterbury>: A violent rain fell suddenly on Canterbury so that the greater part of the city was suddenly Doe (2016) inundated and there was such swelling of the water that the crypt of the church and the cloisters of the (Hamilton monastery were filled with water’. ‘Trees and hedges were overthrown whereby to proceed was not possible 1848-49) either to men or horses and many were imperilled by the force of waters flowing in the streets and in the houses of citizens’. 20 May 1739 <Cobham>, Surrey: The greatest storm of thunder rain and hail ever known with hail larger than the biggest Derby marbles. Incredible damage done. Mercury 8 Aug 1877 3 Jun 1747 <Midhurst> Sussex: In a thunderstorm a bridge on the <<Arun>> was carried away. Water was several feet deep Gentlemans in the church and churchyard. Sheep were drowned and two men were killed by lightning. Mag 12 Jun 1748 <Addington Place> Surrey: A thunderstorm with hail affected Surrey (and <Chelmsford> Essex and Warwick). Gentlemans Hail was 7 inches in circumference. Great damage was done to windows and gardens. Mag 10 Jun 1750 <Sittingbourne>, Kent: Thunderstorm killed 17 sheep in one place and several others. -

Kent Archæological Society Library

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society KENT ARCILEOLOGICAL SOCIETY LIBRARY SIXTH INSTALMENT HUSSEY MS. NOTES THE MS. notes made by Arthur Hussey were given to the Society after his death in 1941. An index exists in the library, almost certainly made by the late B. W. Swithinbank. This is printed as it stands. The number given is that of the bundle or box. D.B.K. F = Family. Acol, see Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Benenden, 12; see also Petham. Ady F, see Eddye. Bethersden, 2; see also Charing Deanery. Alcock F, 11. Betteshanger, 1; see also Kent: Non- Aldington near Lympne, 1. jurors. Aldington near Thurnham, 10. Biddend.en, 10; see also Charing Allcham, 1. Deanery. Appledore, 6; see also Kent: Hermitages. Bigge F, 17. Apulderfield in Cudham, 8. Bigod F, 11. Apulderfield F, 4; see also Whitfield and Bilsington, 7; see also Belgar. Cudham. Birchington, 7; see also Kent: Chantries Ash-next-Fawkham, see Kent: Holy and Woodchurch-in-Thanet. Wells. Bishopsbourne, 2. Ash-next-Sandwich, 7. Blackmanstone, 9. Ashford, 9. Bobbing, 11. at Lese F, 12. Bockingfold, see Brenchley. Aucher F, 4; see also Mottinden. Boleyn F, see Hever. Austen F (Austyn, Astyn), 13; see also Bonnington, 3; see also Goodneston- St. Peter's in Tha,net. next-Wingham and Kent: Chantries. Axon F, 13. Bonner F (Bonnar), 10. Aylesford, 11. Boorman F, 13. Borden, 11. BacIlesmere F, 7; see also Chartham. Boreman F, see Boorman. Baclmangore, see Apulderfield F. Boughton Aluph, see Soalcham. Ballard F, see Chartham. -

Railways List

A guide and list to a collection of Historic Railway Documents www.railarchive.org.uk to e mail click here December 2017 1 Since July 1971, this private collection of printed railway documents from pre grouping and pre nationalisation railway companies based in the UK; has sought to expand it‟s collection with the aim of obtaining a printed sample from each independent railway company which operated (or obtained it‟s act of parliament and started construction). There were over 1,500 such companies and to date the Rail Archive has sourced samples from over 800 of these companies. Early in 2001 the collection needed to be assessed for insurance purposes to identify a suitable premium. The premium cost was significant enough to warrant a more secure and sustainable future for the collection. In 2002 The Rail Archive was set up with the following objectives: secure an on-going future for the collection in a public institution reduce the insurance premium continue to add to the collection add a private collection of railway photographs from 1970‟s onwards provide a public access facility promote the collection ensure that the collection remains together in perpetuity where practical ensure that sufficient finances were in place to achieve to above objectives The archive is now retained by The Bodleian Library in Oxford to deliver the above objectives. This guide which gives details of paperwork in the collection and a list of railway companies from which material is wanted. The aim is to collect an item of printed paperwork from each UK railway company ever opened. -

In Celebration of Charles Dickens

Charles Dickens spent the last years of his life, from 1853 to 1870 living at Higham, Rochester. He died while writing The Mystery of Edwin Drood in his Swiss Chalet (pictured, from the collections of the Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre.), in the grounds of his house, Gad’s Hill Place. DICKES AT HIGHAM, 1870 Thames Marshes with Issue Number 26: May 2012 Meandering twisting ditches £2.00 ; free to members Giving way to Copperfields and hills, By Rudge and Barn, In Celebration of Charles Dickens No Bleak Houses, No Cities here – Just Little Droody Dorritts With Martins and swallows Nesting in Chuzzley Nicks Until, at last, a-top the Gadding Hill Picking Carols to celebrate St. Nicholas And Expecting more imagination, Dickens Sits in his Swiss Chalet. Odette Buchanan Some Dickens characters. From the collections of the Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre. If undelivered, please return to: Medway Archives office, th Civic Centre, Strood, Rochester, Kent, To commemorate the 200 birthday of local author Charles Dickens ME2 4AU. (1812–1870), The Clock Tower looks at some lesser known aspects of his association with the Medway Towns. Photograph from the Percy Fitzgerald Collection at the Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre. Colour picture postcard entitled Charles Dickens at Home, Gad’s Hill, Kent comprising view northern elevation of Gadshill Place, Gravesend Road, Higham, looking from north-east corner of garden, showing in foreground part of lawn, drive, shrubs and gaunt male figure looking at artist and in background house, porch, shrubs and trees. On rear, message from Alice [-] to a Miss Gurney, Rede Court, Strood, wishing her many happy returns. -

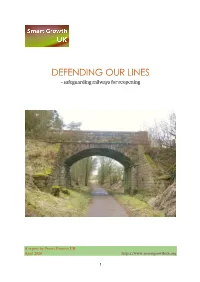

DEFENDING OUR LINES - Safeguarding Railways for Reopening

DEFENDING OUR LINES - safeguarding railways for reopening A report by Smart Growth UK April 2020 http://www.smartgrowthuk.org 1 Contents __________________________________________________________________________________ Foreword by Paul Tetlaw 4 Executive summary 6 1. Introduction 8 2. Rail closures 9 3. Reopening and reinstatement 12 4. Obstacles to reinstatement of closed lines 16 5. Safeguarding alignments 19 6. Reopening and the planning system 21 7. Reopening of freight-only or mothballed lines 24 8. Reinstatement of demolished lines 29 9. New railways 38 10. Conclusions 39 Appendix 1 41 2 Smart Growth UK __________________________________________________________________________ Smart Growth UK is an informal coalition of organisations and individuals who want to promote the Smart Growth approach to planning, transportation and communities. Smart Growth is an international movement dedicated to more sustainable approaches to these issues. In the UK it is based around a set of principles agreed by the organisations that support the Smart Growth UK coalition in 2013:- Urban areas work best when they are compact, with densities appropriate to local circumstances but generally significantly higher than low-density suburbia and avoiding high-rise. In addition to higher density, layouts are needed that prioritize walking, cycling and public transport so that they become the norm. We need to reduce our dependence on private motor vehicles by improving public transport, rail-based where possible, and concentrating development in urban areas. We should protect the countryside, farmland, natural beauty, open space, soil and biodiversity, avoiding urban sprawl and out-of-town development. We should protect and promote local distinctiveness and character and our heritage, respecting and making best use of historic buildings, street forms and settlement patterns. -

0 Medieval Flokestone Robertson

http://kentarchaeology.org.uk/research/archaeologia-cantiana/ Kent Archaeological Society is a registered charity number 223382 © 2017 Kent Archaeological Society ( civ ) MEDIAEVAL FOLKESTONE. FOLKESTONE gives its name to one of the Hundreds of Kent, and was the site of a nunnery (said to have been the first in England), founded in the seventh century by Eadbald, King of Kent, the father of St. Eanswith, its first Abbess. These facts prove that the town was in earlier times a place of some importance, but very little is known respecting its history, prior to the Middle Ages. It is evident that the name, spelt Polcstane in the earlier records, was given by the Saxons,* and that it was derived from the natural peculiarities of the place, its stone quarries having always played a conspicuous part in its history. They are mentioned in two extents (or valuations) of the manor of " Folcstane" which were made in the reign, of Henry III. In the first of these, dated 1263, we read that "there are there certain quarries worth per annum-)- 20s." The second gives us further information; it is dated 1271, and says "the quarry J in which mill-stones and handmill- stones are dug " is worth 20s. per annum. Such peaceful and useful implements as mill-stones were, however, by no means the only produce of these quarries. When Edward III., and his son the Black Prince, were prosecuting their conquests in France, some of the implements of war were obtained from Folkestone. On Jan. the 9th, 1356,§ the King ordered the Warden of the Cinque Ports to send over to Calais|| those stones for warlike engines which had been prepared at Folkestone. -

Infrastructure Delivery Plan 2017 Ashford Borough

ASHFORD BOROUGH COUNCIL EXAMINATION LIBRARY SD10 Ashford Borough Council INFRASTRUCTURE DELIVERY PLAN 2017 1 CONTENTS Introduction p3 Background and context p5 Prioritisation p7 Overview of Infrastructure p12 Theme 1: Transport p13 Theme 2: Education p24 Theme 3: Energy p28 Theme 4: Water p32 Theme 5: Health and Social Care p38 Theme 6: Community Facilities p43 Theme 7: Sport and Recreation p47 Theme 8: Green Infrastructure / Biodiversity p54 Theme 9: Waste and Recycling p64 Theme 10: Public Realm p66 Theme 11: Art and Cultural Industries p67 Appendix 1: Links to evidence and management plans Appendix 2: Examples of letters to stakeholders and providers Appendix 3 & 4: Responses from our requests for information Appendix 5: Liaison with key stakeholders Appendix 6: The growth scenarios tested 2 Introduction 1.1 This Infrastructure Plan has been produced by Ashford Borough Council (the Council). The Infrastructure Delivery Plan (IDP) provides: • background and context to key infrastructure that has been delivered recently or is in the process of being delivered, • an analysis of existing infrastructure provision, • stresses in the current provision, • what is needed to meet the existing and future needs and demands for the borough to support new development and a growing population, as envisaged through the Council’s emerging Local Plan 2030. 1.2 The IDP has been informed through discussion and consultation with relevant service providers operating in the Borough, alongside reviewing existing evidence and publications (such as management plans). 1.3 The IDP is supported by various appendices, as follows: • Appendix 1: Links to evidence and management plans – several stakeholders steered us towards their respective management plans and publications as a way of responding to our consultation and questions. -

Kentish Weald

LITTLE CHART PLUCKLEY BRENCHLEY 1639 1626 240 ACRES (ADDITIONS OF /763,1767 680 ACRES 8 /798 OMITTED) APPLEDORE 1628 556 ACRES FIELD PATTERNS IN THE KENTISH WEALD UI LC u nmappad HORSMONDEN. NORTH LAMBERHURST AND WEST GOUDHURST 1675 1175 ACRES SUTTON VALENCE 119 ACRES c1650 WEST PECKHAM &HADLOW 1621 c400 ACRES • F. II. 'educed from orivinals on va-i us scalP5( 7 k0. U 1I IP 3;17 1('r 2; U I2r/P 42*U T 1C/P I;U 27VP 1; 1 /7p T ) . mhe form-1 re re cc&— t'on of woodl and blockc ha c been sta dardised;the trees alotw the field marr'ns hie been exactly conieda-3 on the 7o-cc..onen mar ar mar1n'ts;(1) on Vh c. c'utton vPlence map is a divided fi cld cP11 (-1 in thP ace unt 'five pieces of 1Pnii. THE WALDEN LANDSCAPE IN THE EARLY SEVENTEENTH CENTERS AND ITS ANTECELENTS Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the University of London by John Louis Mnkk Gulley 1960 ABSTRACT This study attempts to describe the historical geography of a confined region, the Weald, before 1650 on the basis of factual research; it is also a methodological experiment, since the results are organised in a consistently retrospective sequence. After defining the region and surveying its regional geography at the beginning of the seventeenth century, the antecedents and origins of various elements in the landscape-woodlands, parks, settlement and field patterns, industry and towns - are sought by retrospective enquiry. At two stages in this sequence the regional geography at a particular period (the early fourteenth century, 1086) is , outlined, so that the interconnections between the different elements in the region should not be forgotten. -

Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre

GB 1204 Ch 46 Medway Archives and Local Studies Centre This catalogue was digitised by The National Archives as part of the National Register of Archives digitisation project NRA 22324 ! National Arc F Kent Archives Offic Ch 46 Watts Charity MSS., 1579-1972 Deposited by Mr. Chinnery, Clerk to the Charity, Rochester, 1st May 1974, and 5th February, 1976 Catalogued by Alison Revell, June 1978 INTRODUCTION For information concerning the establishment of Watts's Charity, under Richard Watts of Rochester's will, in 1579 and its subsequent history, The Report of Commissioners for Inquiring Concerning Charities - Kent, 1815-39 Pp. 504-9, provides most of the basic facts. Other Rochester Charities are dealt with in the same Report (see pages 55-57, and 500-513). The Report also deals with various early legal cases concerning the Charity, and the uses to which its funds should be put, most notably the cases of the parishes of St. Margaret 's Rochester, and Strood, against the parishioners of St. Nicholas in 1680, and of the parishioners of Chatham against the Trustees of the Charity in 1808 (see L1-4B in this catalogue). The original will of Richard Watts, drawn up in 1579 and proved in the following year in the Consistory Court of Rochester, is kept in this Office under the catalogue mark, DRb PW12 (1579), with a registered copy in the volume of registered wills, DRb PWr 16 (ffl05-107). A copy is also catalogued in this collection as Ch46 L1A. Further Watts Charity material is found in the Dean and Chapter of Rochester MSS, under the KAO catalogue number, DRc Cl/1-65, and consists mainly of accounts of the Providers of the Poor of Rochester, between the years 1699 and 1819. -

Maidstone's Biodiversity Strategy

Maidstone’s Biodiversity Strategy: A Local Biodiversity Action Plan 2009-2014 Rivers Action Plan Maidstone’s Biodiversity Strategy A Local Biodiversity Action Plan Phase 1: 2009 – 2014 HAP 11: Rivers 1 | P a g e Maidstone’s Biodiversity Strategy: A Local Biodiversity Action Plan 2009-2014 Rivers Action Plan Table of Contents Description ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. 3 National status ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 4 Local status ................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................ 4 Factors causing decline in biodiversity ...................................................................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Current national action ............................................................................................................................................................................................................................................. -

Maidstone Area Archaeological Group, Should Be Sent to Jess Obee (Address at End) Or Payments Made at One of the Meetings

Maidstone Area Archaeological Group Newsletter, March 2000 Dear Fellow Members As there is a host of announcements, I will hold over the Editorial until the next Newsletter, due in May (sighs of relief all round). David Carder Subscriptions and Membership Cards Subscriptions for the year beginning 1st April 2000 are now due. Please use the renewal form enclosed with this Newsletter, and complete as much as of it as possible - that way we can establish what members' interests really are. Return the form with your cheque by post to Jess Obee (address at end), or hand it with cheque or cash to any Committee Member who will give you a receipt. Renewing members will receive a handy Membership Card with the May Newsletter, giving details of indoor meetings, subscription rates, and contacts. In order to comply with the data protection legislation, we have included on the form a consent that your details may be held on a computer database. This data is held purely for membership administration (e.g. printing of address labels and registration of subscription payments). It will not be used for other purposes, or released to outside parties without your express consent. If you have any queries or concerns over this, please write to the Chairman. Notice of Annual General Meeting - Friday 28th April 2000 This year's AGM will be held at 7.30 pm on Friday 28th April 2000 (not 21st as previously published) at the School Hall, The Street, Detling. The Agenda is as follows : 1. Chairman's welcome 2. Apologies for absence 3. -

Landscape Assessment of Kent 2004

CHILHAM: STOUR VALLEY Location map: CHILHAMCHARACTER AREA DESCRIPTION North of Bilting, the Stour Valley becomes increasingly enclosed. The rolling sides of the valley support large arable fields in the east, while sweeps of parkland belonging to Godmersham Park and Chilham Castle cover most of the western slopes. On either side of the valley, dense woodland dominate the skyline and a number of substantial shaws and plantations on the lower slopes reflect the importance of game cover in this area. On the valley bottom, the river is picked out in places by waterside alders and occasional willows. The railway line is obscured for much of its length by trees. STOUR VALLEY Chilham lies within the larger character area of the Stour Valley within the Kent Downs AONB. The Great Stour is the most easterly of the three rivers cutting through the Downs. Like the Darent and the Medway, it too provided an early access route into the heart of Kent and formed an ancient focus for settlement. Today the Stour Valley is highly valued for the quality of its landscape, especially by the considerable numbers of walkers who follow the Stour Valley Walk or the North Downs Way National Trail. Despite its proximity to both Canterbury and Ashford, the Stour Valley retains a strong rural identity. Enclosed by steep scarps on both sides, with dense woodlands on the upper slopes, the valley is dominated by intensively farmed arable fields interspersed by broad sweeps of mature parkland. Unusually, there are no electricity pylons cluttering the views across the valley. North of Bilting, the river flows through a narrow, pastoral floodplain, dotted with trees such as willow and alder and drained by small ditches.