Amazing Words, Lederer Puts on Yet Another Dazzling Display, Elucidating the Wondrous Stories and Secrets That Lie Hidden in the Language

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Charles Dickens, 'Hard Times' and Hyperbole Transcript

Charles Dickens, 'Hard Times' and Hyperbole Transcript Date: Tuesday, 15 November 2016 - 6:00PM Location: Museum of London 15 November 2016 Charles Dickens: Hard Times and Hyperbole Professor Belinda Jack As I said in my last lecture, ‘Rhetoric’ has a bad name. Phrases like ‘empty rhetoric’, ‘it’s just rhetoric’ and the like suggest that the main purpose of rhetoric is to deceive. This, of course, can be true. But rhetoric is also an ancient discipline that tries to make sense of how we persuade. Now we could argue that all human communication sets out to persuade. Even a simple rhetorical question as clichéd and mundane as ‘isn’t it a lovely day?’ could be said to have a persuasive element. So this year I want to explore the nuts and bolts of rhetoric in relation to a number of famous works of literature. What I hope to show is that knowing the terms of rhetoric helps us to see how literature works, how it does its magic, while at the same time arguing that great works of literature take us beyond rhetoric. They push the boundaries and render the schema of rhetoric too rigid and too approximate. In my first lecture in the new series we considered Jane Austen’s novel entitled Persuasion (1817/1818) – what rhetoric is all about – in relation to irony and narrative technique, how the story is told. I concluded that these two features of Austen’s last completed novel functioned to introduce all manner of ambiguities leaving the reader in a position of uncertainty and left to make certain choices about how to understand the novel. -

The Longest Words Using the Fewest Letters

The Longest Words Using The Fewest Letters David M. Rheingold / Barnstable, Massachusetts Austin Byl, Evan Crouch, Elizabeth Krodel, Celia Schiffman, Nico Toutenhoofd / Boulder, Colorado Claude Shannon may be remembered as the father of information theory for the formula engraved on his tombstone, but it’s not the only measure of entropy he helped devise. Metric entropy gauges the amount of information proportionate to the number of unique characters in a message. Within the English language, the maximum metric entropy individual words can attain is 0.5283 binary digits (or bits). This is the value of any three-letter word composed of three different letters (e.g., WHO). Multiplying 0.5283 times the number of distinct letters equals 1.58, and 2 raised to the power of 1.58 yields the same number of letters. These values hold true for any trigram with three different letters in a 26-letter alphabet. Measurements differ for written text involving other characters including numbers, punctuation, even spaces. Distinguishing between uppercase and lowercase would double the number of letters to 52. Adjusting for word frequency would further alter values as trigrams like WHO occur far more often in written English than, say, KEY. (How much more often? We found 3,598,284 instances of WHO in Project Gutenberg versus 58,863 of KEY, or 61 times as many.) Our lexicon derives from three primary sources: Merriam-Webster, Webster’s, and the Moby II wordlist, with a combined 382,843 words. Of these we find some 2,000 trigrams made up of three different letters, including WHO and KEY, tied for highest metric entropy. -

Fourth Sunday of Advent $36,705 Was Added to Our Capital Campaign Fund

participating. All pledges have been fulfilled. After meeting our $10,500 commitment to the Diocese, Fourth Sunday of Advent $36,705 was added to our Capital Campaign Fund. December 20, 2020 First Reading: 2 Samuel 7:1-5, 8b-12, 14a, 16; Psalm 24; Second Reading: Romans 16:25-27; Gospel of Luke 1:26-38 “May it be done to me according to your word.”—Luke 1:38 Like young Mary, each of us has the power to choose. We have the power to choose how we respond to the mysteries that come our way as we follow Christ. To love or not. To place our faith and trust in God or not. When we are confronted with choices to do God’s will, we can call these Mary Moments. Mary understood that there would be a cost. And the GOSPEL READINGS angel of GodThanksgiving said to her, “MorningDo not be Eucharist afraid, Mary, for you have found favor FOR THE WEEK with God. ” Listening to God’s word gives Mary peace and confidence in We will celebrate a special Mass in gratitude to God on Mon: Luke 1:39-45 God ’s presence and faithfulness. She responds with a loving and trusting Thanksgiving morning, Thursday, Nov. 26 at 10:00 am. Tues: Luke 1:46-56 heart, “May it be done to me according to your word.” This final Sunday of You are welcome to bring any food items that will be Wed: Luke 1:57-66 Advent reminds us of the importance of opening our hearts to God’s love shared at your table for a special blessing, as well as to Thurs: Luke 2:1-14 in every Mary Moment that comes our way. -

'James Cameron's Story of Science Fiction' – a Love Letter to the Genre

2 x 2" ad 2 x 2" ad April 27 - May 3, 2018 A S E K C I L S A M M E L I D 2 x 3" ad D P Y J U S P E T D A B K X W Your Key V Q X P T Q B C O E I D A S H To Buying I T H E N S O N J F N G Y M O 2 x 3.5" ad C E K O U V D E L A H K O G Y and Selling! E H F P H M G P D B E Q I R P S U D L R S K O C S K F J D L F L H E B E R L T W K T X Z S Z M D C V A T A U B G M R V T E W R I B T R D C H I E M L A Q O D L E F Q U B M U I O P N N R E N W B N L N A Y J Q G A W D R U F C J T S J B R X L Z C U B A N G R S A P N E I O Y B K V X S Z H Y D Z V R S W A “A Little Help With Carol Burnett” on Netflix Bargain Box (Words in parentheses not in puzzle) (Carol) Burnett (DJ) Khaled Adults Place your classified ‘James Cameron’s Story Classified Merchandise Specials Solution on page 13 (Taraji P.) Henson (Steve) Sauer (Personal) Dilemmas ad in the Waxahachie Daily Merchandise High-End (Mark) Cuban (Much-Honored) Star Advice 2 x 3" ad Light, Midlothian1 x Mirror 4" ad and Deal Merchandise (Wanda) Sykes (Everyday) People Adorable Ellis County Trading Post! Word Search (Lisa) Kudrow (Mouths of) Babes (Real) Kids of Science Fiction’ – A love letter Call (972) 937-3310 Run a single item Run a single item © Zap2it priced at $50-$300 priced at $301-$600 to the genre for only $7.50 per week for only $15 per week 6 lines runs in The Waxahachie Daily2 x Light,3.5" ad “AMC Visionaries: James Cameron’s Story of Science Fiction,” Midlothian Mirror and Ellis County Trading Post premieres Monday on AMC. -

Peace, Good Will and Happiness for You at Christmas and in the New Year

P.O. Box 407, Bonaire, Netherlands Antilles, Phone 790-6518, 786-6125, www.bonairereporter.com email: [email protected] Since 1994 Printed every fortnight On-line every day, 24/7 Greta Kooistra photo Cyndell Dowling, Gabriella and Evita Thodé(with camera). Cyndell and Gabriella performed a cappella a delightful song they composed about the Shelter and its puppies and kittens. Peace, good will and happiness for you at Christmas and in the New Year. Bonaire Government photo TableThis Week’s of Contents Stories PHU Voting Lawsuit 2 New Prison in Bonaire 3 Referendum 3 Dr. Miguel A. González (English & Span- ish) Committed to Serve 4 Bonaire By Bike 7 Potholes 8 European Kid Freestyle Tour 9 Lions Windsurfing 9 Funchi Ayo 10 Church On The Rise 11 Kriabon Open House 11 Harbourtown Grand Opening 12 Karate Win 14 Letters to the Editor 18 he foundations for the DAE, Floris van Pallandt, said he About 25% of Bonaire’s population consists of immigrants.- Zwarte Piet Healed 18 T sewage treatment plant would remain as an advisor to the 2008 Civil Registry (Bevolking) figures. Kunuku Kids Open House 20 are near completion. They are new CEO for the time being. Holiday Concert 20 being built by the company MNO Leonora was born in Curaçao XThe Party for Justice and Unity (Partido pro Hustisia & Animal Shelter Auction 21 Vervat at the LVV site. When and studied Airline Business Ad- Union -PHU) has filed a lawsuit in order to force the ———————————————— complete, the target is March ministration, Management and government to grant voting rights for local elections to Departments 2011, sewage waste from the prop- Finance. -

Improvement Session, 8/6-7/76 - Press Advance (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R

The original documents are located in Box 24, folder “Press Office - Improvement Session, 8/6-7/76 - Press Advance (2)” of the Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Copyright Notice The copyright law of the United States (Title 17, United States Code) governs the making of photocopies or other reproductions of copyrighted material. Ron Nessen donated to the United States of America his copyrights in all of his unpublished writings in National Archives collections. Works prepared by U.S. Government employees as part of their official duties are in the public domain. The copyrights to materials written by other individuals or organizations are presumed to remain with them. If you think any of the information displayed in the PDF is subject to a valid copyright claim, please contact the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library. Digitized from Box 24 of The Ron Nessen Papers at the Gerald R. Ford Presidential Library AGENDA FOR MEETING WITH PRESS SECRETARY Friday, August 6, 1976 4:00 p.m. Convene Meeting - Roosevelt Room (Ron) 4:05p.m. Overview from Press Advance Office (Doug) 4:15 p.m. Up-to-the-Minute Report from Kansas City {Dave Frederickson) 4:20 p.m. The Convention (Ron} 4:30p.m. The Campaign (Ron) 4:50p.m. BREAK 5:00p.m. Reconvene Meeting - Situation Room (Ron) 5:05 p. in. Presentation of 11 Think Reports 11 11 Control of Image-Making Machinery11 (Dorrance Smith) 5:15p.m. "Still Photo Analysis - Ford vs. Carter 11 (David Wendell) 5:25p.m. Open discussion Reference July 21 memo, Blaser to Carlson "What's the Score 11 6:30p.m. -

Language in India

LANGUAGE IN INDIA Strength for Today and Bright Hope for Tomorrow Volume 16:11 November 2016 ISSN 1930-2940 Managing Editor: M. S. Thirumalai, Ph.D. Editors: B. Mallikarjun, Ph.D. Sam Mohanlal, Ph.D. B. A. Sharada, Ph.D. A. R. Fatihi, Ph.D. Lakhan Gusain, Ph.D. Jennifer Marie Bayer, Ph.D. S. M. Ravichandran, Ph.D. G. Baskaran, Ph.D. L. Ramamoorthy, Ph.D. C. Subburaman, Ph.D. (Economics) N. Nadaraja Pillai, Ph.D. Renuga Devi, Ph.D. Soibam Rebika Devi, M.Sc., Ph.D. Assistant Managing Editor: Swarna Thirumalai, M.A. Contents Materials published in Language in India www.languageinindia.com are indexed in EBSCOHost database, MLA International Bibliography and the Directory of Periodicals, ProQuest (Linguistics and Language Behavior Abstracts) and Gale Research. The journal is included in the Cabell’s Directory, a leading directory in the USA. Articles published in Language in India are peer-reviewed by one or more members of the Board of Editors or an outside scholar who is a specialist in the related field. Since the dissertations are already reviewed by the University-appointed examiners, dissertations accepted for publication in Language in India are not reviewed again. This is our 16th year of publication. All back issues of the journal are accessible through this link: http://languageinindia.com/backissues/2001.html Language in India www.languageinindia.com ISSN 1930-2940 16:11 November 2016 Contents i Jimmy Teo THE 7 PILLARS OF THE HEALTH & SANITY iv-v Adiba Murtaza, M.A. Students’ Perceptions of English Language Instruction (EMI) at a Private University in Bangladesh: A Survey 1-11 K. -

The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy

Mount Rushmore: The Rise of Talk Radio and Its Impact on Politics and Public Policy Brian Asher Rosenwald Wynnewood, PA Master of Arts, University of Virginia, 2009 Bachelor of Arts, University of Pennsylvania, 2006 A Dissertation presented to the Graduate Faculty of the University of Virginia in Candidacy for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of History University of Virginia August, 2015 !1 © Copyright 2015 by Brian Asher Rosenwald All Rights Reserved August 2015 !2 Acknowledgements I am deeply indebted to the many people without whom this project would not have been possible. First, a huge thank you to the more than two hundred and twenty five people from the radio and political worlds who graciously took time from their busy schedules to answer my questions. Some of them put up with repeated follow ups and nagging emails as I tried to develop an understanding of the business and its political implications. They allowed me to keep most things on the record, and provided me with an understanding that simply would not have been possible without their participation. When I began this project, I never imagined that I would interview anywhere near this many people, but now, almost five years later, I cannot imagine the project without the information gleaned from these invaluable interviews. I have been fortunate enough to receive fellowships from the Fox Leadership Program at the University of Pennsylvania and the Corcoran Department of History at the University of Virginia, which made it far easier to complete this dissertation. I am grateful to be a part of the Fox family, both because of the great work that the program does, but also because of the terrific people who work at Fox. -

Hagbimilan2.Pdf

«The Holy Letters Had Never Joined into Any Name as Mine» Notes on the Name of the Author in Agnon’s Work1 Yaniv Hagbi University of Amsterdam 1. Nomen est Omen As the famous Latin proverb testifies, the correlation between characters’ names and their nature, occupation, destiny or history is a literary trope very common in world-literature. It is known at least since the Bible. Abraham received his name because God is going to make him «the father of multitudes» or in Hebrew “av hamon goyim” (Gen. 17:5). Pharos’ daughter’s (surprisingly) good command of the language of the slaves, enabled her to name her Hebrew foundling, Moshe, saying, “I drew him out of the water (meshitihu)”» (Ex. 2:10).2 As one may presume this literary tool is only part of larger literary device. Proper names, i.e. not only persons’ names but all names of specific objects such as places, plants, animals etc., can bear literary aesthetic value. That latter, broader phenomenon is also known as onomastics (literary onomastics). The narrower manifestation of that phenomenon, with which we started, i.e. the relationship between a name and its human bearers, might be dubbed as anthropo-onomastics or anthroponym.3 It is of no surprise that the use of that trope is very common in the work of Shmuel Yosef Agnon (Tchatchkes) (1888-1970), an author well-versed in both Jewish literature and thought, as well as in world-literature.4 In the following article we shall see several unique uses Agnon makes in that trope while trying to account for possible reasons lying at the core of his poetical worldview. -

June 2020 #211

Click here to kill the Virus...the Italian way INSIDE THIS ISSUE: Table of Contents 1 Notams 2 Admin Reports 3-4-5 Covid19 Experience Flying the Line with Covid19 Paul Soderlind Scholarship Winners North Country Don King Atkins Stratocruiser Contributing Stories from the Members Bits and Pieces-June Gars’ Stories From here on out the If you use and depend on the most critical thing is NOT to RNPA Directory FLY THE AIRPLANE. you must keep your mailing address(es) up to date . The ONLY Instead, you MUST place that can be done is to send KEEP YOUR EMAIL UPTO DATE. it to: The only way we will have to The Keeper Of The Data Base: communicate directly with you Howie Leland as a group is through emails. Change yours here ONLY: [email protected] (239) 839-6198 Howie Leland 14541 Eagle Ridge Drive, [email protected] Ft. Myers, FL 33912 "Heard about the RNPA FORUM?" President Reports Gary Pisel HAPPY LOCKDOWN GREETINGS TO ALL MEMBERS Well the past few weeks and months have been a rude awakening for our past lifestyles. Vacations and cruises cancelled, all the major league sports cancelled, the airline industry reduced to the bare minimum. Luckily, I have not heard of many pilots or flight attendants contracting COVID19. Hopefully as we start to reopen the USA things will bounce back. The airlines at present are running at full capacity but with several restrictions. Now is the time to plan ahead. We have a RNPA cruise on Norwegian Cruise Lines next April. Things will be back to the new normal. -

In Praise of Her Supreme Holiness Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi

In praise of Her Supreme Holiness Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi 2016 Edition The original Sahaja Yoga Mantrabook was compiled by Sahaja Yoga Austria and gibven as a Guru Puja gift in 1989 0 'Now the name of your Mother is very powerful. You know that is the most powerful name, than all the other names, the most powerful mantra. But you must know how to take it. With that complete dedication you have to take that name. Not like any other.' Her Supreme Holiness Shri Mataji Nirmala Devi ‘Aum Twameva sakshat, Shri Nirmala Devyai namo namaḥ. That’s the biggest mantra, I tell you. That’s the biggest mantra. Try it’ Birthday Puja, Melbourne, 17-03-85. 1 This book is dedicated to Our Beloved Divine M other Her Supreme Holiness Shri MMMatajiM ataji Nirmal aaa DevDeviiii,,,, the Source of This Knowledge and All Knowledge . May this humble offering be pleasing in Her Sight. May Her Joy always be known and Her P raises always sung on this speck of rock in the Solar System. Feb 2016 No copyright is held on this material which is for the emancipation of humanity. But we respectfully request people not to publish any of the contents in a substantially changed or modified manner which may be misleading. 2 Contents Sanskrit Pronunciation .................................... 8 Mantras in Sahaja Yoga ................................... 10 Correspondence with the Chakras ....................... 14 The Three Levels of Sahasrara .......................... 16 Om ................................................. 17 Mantra Forms ........................................ 19 Mantras for the Chakras .................................. 20 Mantras for Special Purposes ............................. 28 The Affirmations ......................................... 30 Short Prayers for the Chakras ............................. 33 Gāyatrī Mantra ...................................... -

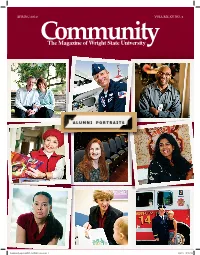

Community-Spring 2010 ALUMNI Issue.Indd 1 5/6/10 10:33 AM F ROM the P RESIDENT ’ S D ESK INSIDE SPRING 2010 VOLUME XV NO

SPRING 2010 VOLUME XV NO. 2 The Magazine of Wright State University Community-Spring 2010 ALUMNI Issue.indd 1 5/6/10 10:33 AM F ROM THE P RESIDENT ’ S D ESK INSIDE SPRING 2010 VOLUME XV NO. 2 IN FALL 2009, we began a new alumni engagement Publisher initiative called “Wright State on the Road.” Over the David R. Hopkins last several months, I have had the great pleasure President of Wright State University of traveling throughout the country and across the COVER STORY Associate Vice President for Communications 16-county region we call “Raider Country” to meet and Marketing hundreds of Wright State University’s accomplished 6 ALUMNI PORTRAITS George Heddleston alumni. From the stages of Juilliard to the cockpit of an F-16, Wright State alumni are making Managing Editor It has been a real privilege to visit with our their mark across the country. Denise Robinow graduates, fi nd out what’s going on in their lives, and Editor share with them the many exciting and innovative FEATURES Kim Patton projects that are happening at Wright State. While Design everyone has a different story, the one thing all of our 24 MAKING WAVES Theresa Almond alumni have in common is their tremendous pride in Wright State. From inspecting the space shuttle for cracks to spotting nervous terrorists, terahertz light waves are the specialty of Elliott Brown, the newest addition to Wright State’s Contributing Writers In this issue of Community you’ll meet some of the friends I have made “on College of Engineering and Computer Science.