Twelfth Night Music Credits

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

T.C. ISTANBUL AYDIN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE of SOCIAL SCIENCES the CRITIQUE of NEOLIBERALISM in DAVID HARE's PLAYS Phd THESİS Ha

T.C. ISTANBUL AYDIN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THE CRITIQUE OF NEOLIBERALISM IN DAVID HARE’S PLAYS PhD THESİS Hakan GÜLTEKİN Department of English Language and Literature English Language and Literature Program Thesis Advisor: Assoc. Prof. (Ph. D.) Ferma LEKESİZALIN June, 2018 ii T.C. ISTANBUL AYDIN UNIVERSITY INSTITUTE OF SOCIAL SCIENCES THE CRITIQUE OF NEOLIBERALISM IN DAVID HARE’S PLAYS PhD THESİS Hakan GÜLTEKİN (Y1414.620014) Department of English Language and Literature English Language and Literature Program Thesis Advisor: Assoc. Prof. (Ph. D.) Ferma LEKESİZALIN June, 2018 ii iv DECLARATION I hereby declare that all information in this thesis document has been obtained and presented in accordance with academic rules and ethical conduct. I also declare that, as required by these rules and conduct, I have fully cited and referenced all material and results, which are not original to this thesis. ( / /2017). Hakan GÜLTEKİN v vi FOREWORD I would like to express my appreciation to my supervisor Assoc. Prof. Dr. Ferma LEKESĠZALIN for her persistent encouragement, guidance, patience, and Dr. Ahmet Gökhan BĠÇER for his erudite comments and invaluable contribution. I am also indebted to Dr. Öz ÖKTEM and Dr. Gamze SABANCI UZUN for supporting me in Istanbul Aydin University days. I would also like to thank Prof. Dr. Mehmet TAKKAÇ for his suggestions. Special thanks go to Prof. Dr. Ġbrahim YEREBAKAN and Dr. Mesut GÜNENÇ, whose encouragements have been of particular note here. I am also grateful to Assoc. Prof. Dr. Gillian Mary Elizabeth ALBAN, Dr. Hüseyin EFE, Dr. Arsev AyĢen ARSLANOĞLU YILDIRAN, Sercan ÖZTEKĠN and Florentina GÜMÜġ for their help during the creation phase of my thesis. -

David Hare Plays 1: Slag; Teeth N Smiles; Knuckle; Licking Hitler; Plenty Pdf

FREE DAVID HARE PLAYS 1: SLAG; TEETH N SMILES; KNUCKLE; LICKING HITLER; PLENTY PDF David Hare | 496 pages | 01 Apr 1996 | FABER & FABER | 9780571177417 | English | London, United Kingdom David Hare Plays 1 | Faber & Faber Plenty is a play by David Harefirst performed inabout British post-war disillusion. The inspiration for Plenty came from the fact that 75 per cent of the women engaged in wartime SOE operations divorced in the immediate post-war years; the title is derived from the idea that the post-war era would be a time of "plenty", which proved untrue for most of England. The play premiered Off-Broadway on 21 Octoberat the Public Theaterwhere it ran for 45 performances. Plenty was revived at Chichester inin the Festival Theatre between June. Susan Traherne, a former secret agent, is a woman conflicted by the contrast between her past, exciting triumphs and her present, more ordinary David Hare Plays 1: Slag; Teeth n Smiles; Knuckle; Licking Hitler; Plenty. However, she regrets the mundane nature of her present life, as the increasingly depressed wife of a diplomat whose career she has destroyed. Susan Traherne's story is told in a non-linear chronologyalternating between her wartime and post-wartime lives, illustrating how youthful dreams rarely are realised and how a person's personal life can affect the outside world. Sources: Playbill; [3] Lortel [2]. From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia. Official London Theatre Guide. Archived from the original on 18 January Retrieved 4 December BBC News. Archived from the original on 27 February Retrieved 5 May CS1 maint: archived copy as title link sheffieldtheatres. -

A STUDY GUIDE by Katy Marriner

© ATOM 2012 A STUDY GUIDE BY KATY MARRINER http://www.metromagazine.com.au ISBN 978-1-74295-267-3 http://www.theeducationshop.com.au Raising the Curtain is a three-part television series celebrating the history of Australian theatre. ANDREW SAW, DIRECTOR ANDREW UPTON Commissioned by Studio, the series tells the story of how Australia has entertained and been entertained. From the entrepreneurial risk-takers that brought the first Australian plays to life, to the struggle to define an Australian voice on the worldwide stage, Raising the Curtain is an in-depth exploration of all that has JULIA PETERS, EXECUTIVE PRODUCER ALINE JACQUES, SERIES PRODUCER made Australian theatre what it is today. students undertaking Drama, English, » NEIL ARMFIELD is a director of Curriculum links History, Media and Theatre Studies. theatre, film and opera. He was appointed an Officer of the Order Studying theatre history and current In completing the tasks, students will of Australia for service to the arts, trends, allows students to engage have demonstrated the ability to: nationally and internationally, as a with theatre culture and develop an - discuss the historical, social and director of theatre, opera and film, appreciation for theatre as an art form. cultural significance of Australian and as a promoter of innovative Raising the Curtain offers students theatre; Australian productions including an opportunity to study: the nature, - observe, experience and write Australian Indigenous drama. diversity and characteristics of theatre about Australian theatre in an » MICHELLE ARROW is a historian, as an art form; how a country’s theatre analytical, critical and reflective writer, teacher and television pre- reflects and shape a sense of na- manner; senter. -

The Australian Theatre Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sydney eScholarship A Chance Gathering of Strays: the Australian theatre family C. Sobb Ah Kin MA (Research) University of Sydney 2010 Contents: Epigraph: 3 Prologue: 4 Introduction: 7 Revealing Family 7 Finding Ease 10 Being an Actor 10 Tribe 15 Defining Family 17 Accidental Culture 20 Chapter One: What makes Theatre Family? 22 Story One: Uncle Nick’s Vanya 24 Interview with actor Glenn Hazeldine 29 Interview with actor Vanessa Downing 31 Interview with actor Robert Alexander 33 Chapter Two: It’s Personal - Functioning Dysfunction 39 Story Two: “Happiness is having a large close-knit family. In another city!” 39 Interview with actor Kerry Walker 46 Interview with actor Christopher Stollery 49 Interview with actor Marco Chiappi 55 Chapter Three: Community −The Indigenous Family 61 Story Three: Who’s Your Auntie? 61 Interview with actor Noel Tovey 66 Interview with actor Kyas Sheriff 70 Interview with actor Ursula Yovich 73 Chapter Four: Director’s Perspectives 82 Interview with director Marion Potts 84 Interview with director Neil Armfield 86 Conclusion: A Temporary Unity 97 What Remains 97 Coming and Going 98 The Family Inheritance 100 Bibliography: 103 Special Thanks: 107 Appendix 1: Interview Information and Ethics Protocols: 108 Interview subjects and dates: 108 • Sample Participant Information Statement: 109 • Sample Participant Consent From: 111 • Sample Interview Questions 112 2 Epigraph: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way. Everything was in confusion in the Oblonsky’s house. The wife had discovered that the husband was carrying on an intrigue with a French girl, who had been a governess in their family, and she had announced to her husband that she could not go on living in the same house with him. -

Neil Armfield

Mr Neil Armfield The honorary degree of Doctor of Letters was conferred upon Neil Armfield at the Faculty of Arts graduation ceremony held at 4.00pm on 21 April 2006. Neil Armfield, photo, courtesy UniNews. Citation Professor Masters, I have the honour to present Neil Armfield for admission to the degree of Doctor of Letters (honoris causa). While Neil Armfield is still only at the midpoint of his brilliant career, he has already made a distinctive contribution to the Arts and Humanities, especially through his work as a director of plays, operas and films, both within Australia and overseas. Neil was born in Sydney and is a graduate of this University, completing his Bachelor of Arts with Honours in English in 1977. While at university he began directing plays for Sydney University Dramatic Society, with such success that he was invited to direct his first professional production for the Nimrod Theatre Company in 1979. This production of David Allen’s Upside Down at the Bottom of the World, a new play about D H Lawrence in Australia, was also a great success and the production was subsequently invited to the 1980 Edinburgh Festival. Neil Armfield became artistic co-director of the Nimrod Theatre Company from 1980-82, confirming his special affinity for new Australian plays with landmark productions of Stephen Sewell’s Traitors and Welcome the Bright World and Louis Nowra’s Inside the Island. In 1983 he was appointed associate director of the Lighthouse Company in Adelaide. He is, however, most strongly associated with the work of Sydney’s Belvoir Street Theatre, having been a member of Company B since its inception in 1984. -

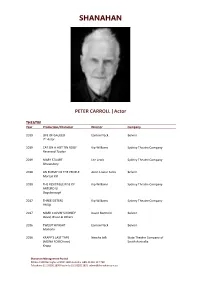

PETER CARROLL |Actor

SHANAHAN PETER CARROLL |Actor THEATRE Year Production/Character Director Company 2019 LIFE OF GALILEO Eamon Flack Belvoir 7th Actor 2019 CAT ON A HOT TIN ROOF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Reverend Tooker 2019 MARY STUART Lee Lewis Sydney Theatre Company Shrewsbury 2018 AN ENEMY OF THE PEOPLE Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Morton Kiil 2018 THE RESISTIBLE RISE OF Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company ARTURO UI Dogsborough 2017 THREE SISTERS Kip Williams Sydney Theatre Company Phillip 2017 MARK COLVIN’S KIDNEY David Berthold Belvoir David, Bruce & Others 2016 TWELFTH NIGHT Eamon Flack Belvoir Malvolio 2016 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of (MONA FOMO tour) South Australia Krapp Shanahan Management Pty Ltd PO Box 1509 Darlinghurst NSW 1300 Australia ABN 46 001 117 728 Telephone 61 2 8202 1800 Facsimile 61 2 8202 1801 [email protected] SHANAHAN 2015 SEVENTEEN Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Tom 2015 KRAPP’S LAST TAPE Nescha Jelk State Theatre Company of Krapp South Australia 2014 CHRISTMAS CAROL Anne-Louise Sarks Belvoir Marley and Other 2014 OEDIPUS REX Adena Jacobs Belvoir Oedipus 2014 NIGHT ON BALD MOUNTIAN Matthew Lutton Malthouse Theatre Mr Hugo Sword 2012-13 CHITTY CHITTY BANG BANG Roger Hodgman TML Enterprises Grandpa Potts 2012 OLD MAN Anthea Williams B Sharp Belvoir (Downstairs) Albert 2011 NO MAN’S LAND Michael Gow QTC/STC Spooner 2011 DOCTOR ZHIVAGO Des McAnuff Gordon Frost Organisation Alexander 2010 THE PIRATES OF PENZANCE Stuart Maunder Opera Australia Major-General Stanley 2010 KING LEAR Marion Potts Bell -

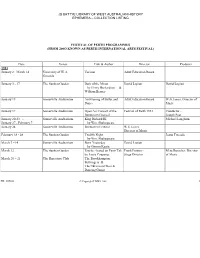

Js Battye Library of West Australian History Ephemera – Collection Listing

JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY EPHEMERA – COLLECTION LISTING FESTIVAL OF PERTH PROGRAMMES (FROM 200O KNOWN AS PERTH INTERNATIONAL ARTS FESTIVAL) Date Venue Title & Author Director Producer 1953 January 2 - March 14 University of W.A. Various Adult Education Board Grounds January 3 - 17 The Sunken Garden Dark of the Moon David Lopian David Lopian by Henry Richardson & William Berney January 15 Somerville Auditorium An Evening of Ballet and Adult Education Board W.G.James, Director of Dance Music January 17 Somerville Auditorium Open Air Concert of the Festival of Perth 1953 Conductor - Beethoven Festival Joseph Post January 20-23 - Somerville Auditorium King Richard III Michael Langham January 27 - February 7 by Wm. Shakespeare January 24 Somerville Auditorium Beethoven Festival W.G.James Director of Music February 18 - 28 The Sunken Garden Twelfth Night Jeana Tweedie by Wm. Shakespeare March 3 –14 Somerville Auditorium Born Yesterday David Lopian by Garson Kanin March 12 The Sunken Garden Psyche - based on Fairy Tale Frank Ponton - Meta Russcher, Director by Louis Couperus Stage Director of Music March 20 – 21 The Repertory Club The Brookhampton Bellringers & The Ukrainian Choir & Dancing Group PR 10960 © Copyright LISWA 2001 1 JS BATTYE LIBRARY OF WEST AUSTRALIAN HISTORY PRIVATE ARCHIVES – COLLECTION LISTING March 25 The Repertory Theatre The Picture of Dorian Gray Sydney Davis by Oscar Wilde Undated His Majesty's Theatre When We are Married Frank Ponton - Michael Langham by J.B.Priestley Stage Director 1954.00 December 30 - March 20 Various Various Flyer January The Sunken Garden Peer Gynt Adult Education Board David Lopian by Henrik Ibsen January 7 - 31 Art Gallery of W.A. -

Wagner Quarterly 130 September 2013

WAGNER SOCIETY nsw ISSUE NO 3 CELEBRATING THE MUSIC OF RICHARD WAGNER WAGNER QUARTERLY 130 SEPTEMBER 2013 IN MEMORIAM Joseph Ferfoglia (c. 1923-2012) – long-time honorary auditor for the Society – see Swan Lines. PRESIDENT’S REPORT Welcome to the third Wagner Quarterly for 2013. I have to confess that I have missed some of our Society’s more recent events, as I have taken my Wagner enthusiasm overseas. I am really sorry not to have attended these events, as on all accounts they have been outstandingly successful. Some fifty people, including her Excellency the Governor, attended the Dutchman seminar. This is described later in this Quarterly, as are the Lisa Gasteen meeting, the “Swords and Winterstorms” concert, and the more recent Neil Armfield talk, which I believe was fascinating. In June this year, I was fortunate enough to attend Ring Cycles in Riga, Milan and Longborough. And in August I went to the third and last cycle of the new Ring production Multiple multi-coloured Masters by Ottmar Hörl capering over in Bayreuth. Unfortunately, because of the decisions relating Bayreuth: Is he welcoming visitors or shooing us away? 300€ at to ticket allocations, there were many fewer Sydneysiders www.Bayreuth-shop.de in Bayreuth than in previous years. But a small ray of hope on this issue remains. In November the matter will again be The Riga Opera House is a jewel of a 19th century opera discussed at a meeting house at one end of a park which divides the mediaeval of the Administrative section of the city from the modern city. -

The Judas Kiss Directed by Michael Michetti

Contact: Niki Blumberg, Tim Choy 323-954-7510 [email protected], [email protected] Boston Court Pasadena presents David Hare’s The Judas Kiss Directed by Michael Michetti February 15 – March 24 Press Opening: February 23 2019 Theatre Season Sponsored by the S. Mark Taper Foundation PASADENA, CA (January 17, 2019) — Boston Court Pasadena commences the 2019 theatre season with a rare production of David Hare’s The Judas Kiss (February 15 – March 24), which tells the story of Oscar Wilde’s love for Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas – and tracking his downfall as he endures a brutal trial and life in exile. Helmed by Artistic Director Michael Michetti, the play examines a literary icon who continues to hold onto his passionate ideals of love and beauty as his life crumbles around him. Sir David Hare, the British playwright behind Plenty, Skylight, and Stuff Happens creates “an emotionally rich drama illuminated by Hare’s customary insight and humanity.” (The Globe and MaiI). The Judas Kiss features Rob Nagle (Oscar Wilde), Colin Bates (Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas), Darius De La Cruz (Robert Ross), Will Dixon (Sandy Moffatt), Matthew Campbell Dowling (Arthur Wellesley), Mara Klein (Phoebe Cane) and Kurt Kanazawa (Galileo Masconi). In spring of 1895, Oscar Wilde was larger than life. His masterpiece, The Importance of Being Earnest, was a hit in the West End and he was the toast of London. Yet by summer he was serving two years in prison for gross indecency. Punished for “the love that dare not speak its name,” Wilde remained devoted to his beloved, Lord Alfred “Bosie” Douglas. -

Postcards from the Gods

More Next Blog» Create Blog Sign In This site uses cookies from Google to deliver its services, to personalize ads and to analyze traffic. Information about your use of this site is shared with Google. By using this site, you agree to its use of cookies. P O S LEARN MTORE GOTC IT A R D S F R O M T H E G O D S T H U R S D A Y , 1 2 M A B Y L O2 G0 1 A6 R C H I V E Drame Princes – Mladinsko, Ljublana ▼ 2016 (49) [seen 07/05/16] ▼ May (5) Drame Princes – Mladinsko, Ljublana Ristić Kompleks – Mladinsko Theatre, Ljubljana Butnskala – Prešernovem gledališču, Kranj ÜberŠkrip – Mladinsko Theatre, Ljubljana The Stage: Should theatre critics need an ‘intelle... ► April (6) ► March (15) I’m not sure I’ve fully got to grips with what to do with the work of ► February (18) Elfriede Jelinek. Or, rather, I’m totally sure I haven’t. It’s problematic ► January (5) work. We know that. It’s “problematic” even if you’re a fluent German speaker and are fully theatre-literate. I’m not even slightly that. And ► 2015 (193) here, with Prinzessinnendramen: Der Tod und das Mädchen I–V, we ► 2014 (154) have the extra problem that I’m watching English surtitles over a ► 2013 (113) production in Slovenian by the Polish director Michał Borczuch. The five pieces are essentially postdramatic monologues alluding to Snow ► 2012 (95) White, Sleeping Beauty, Ingeborg Bachmann, Jacqueline Onassis, and ► 2011 (48) Sylvia Plath – dense reflections on their mythologies and identities as ► 2010 (51) critiques of Austrian patriarchal capitalism. -

Rocky Horror Show Is Back

A BRAND SPANKING NEW PRODUCTION iOTA PAUL CAPSIS TAMSIN CARROLL STARRING IN MEDIA KIT www.rockyhorror.com.au PRESSMEDIA RELEASE RELEASE RICHARD O’BRIEN’S THE WORLD’S FAVOURITE ROCK’N’ROLL MUSICAL DON’T DREAM IT … SEE IT THE WORLD’S FAVOURITE ROCK‘N’ROLL MUSICAL OPENS IN FEBRUARY WITH A BRAND SPANKING NEW PRODUCTION. It’s astounding, time is fleeting and The Rocky Horror Show is back. We’re starting another sensation and we’re definitely not under sedation! A new Australian production of the much-loved Rocky Horror Show will open Sydney’s brand new Star Theatre in February 2008 and tickets go on sale on Monday 27 August. Co-Producer Paul Dainty, Chairman of Dainty Consolidated Entertainment says: “It’s a thrill to be bringing The Rocky Horror Show to the Australian stage. It is a timeless piece of theatre that has spanned decades. I know Australian audiences – both new and old fans – will love this show which stars some of our finest talents.” “This fresh production is an exciting new take on the world’s favourite rock ‘n’ roll musical. It brings together the hottest cast I have seen for a long time” commented co-producer Howard Panter, Joint Chief Executive Officer and Creative Director of the UK’s Ambassador Theatre Group. The Rocky Horror Show is an institution and one of theatre’s most endearing and outrageously fun shows. Its well-known and much-loved storyline goes something like this: Squeaky-clean sweethearts Brad and Janet knock on the door of an eerie house to use the phone after their car breaks down in the rain on a dark and stormy night. -

Theatre and Metatheatre in Hamlet

Theatre and Metatheatre in Hamlet KATE FLAHERTY 'I don't really agree with the notion of setting the plays anywhere in particular. When asked that question about Hamlet I tend to say that it was set on the stage.'-Neil Armfield1 According to his melancholy admission, neither man nor woman delights Hamlet. Yet when a troupe of players arrives at the court of Elsinore, he makes a gleefully reiterated plea that they perform for him; here and now: 'We'll have a speech straight. Come, give us a taste of your quality. Come, a passionate speech.'2 Without hesitation, and to further prompt the Player's performance, he nominates and begins a speech himself. At this moment, theatre is consciously made the centre of the action. It is one of several instances of metatheatre in Hamlet. Others include Rosencrantz's report of the success of the boy players (2.2.319-46), Hamlet's advice to the Players (3.2.1-40), Hamlet's 'antic disposition' and of course 'The Mousetrap' or play-within-the-play (3.2.80-248). Hamlet is a play deeply concerned with notions of play: the power of play, the danger of play3 and the threshold between play and reality. Many of the instances of metatheatricality mentioned above have received insistent critical attention. Hamlet's advice to the Players has been used both to support and to contest the hypothesis that Shakespeare there puts forward a manifesto of naturalism.4 Likewise the play-within-the-play has been taken up repeatedly as a key to the dramatic dynamics of the play by which it is encased.5 Hamlet's 'antic disposition' - whether analysed as a purposeful strategy within a unified psychological profile, or as a complex subversion of representational logic - seems to generate endless speculation.6 The arrival of the Players and the First Player's impromptu performance, however, seem to provoke relatively little inquiry.