The Changing Comparative Advantages of the Hong Kong Watch Industry, 1950–2010

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Japanese Watch Winder

JAPANESE WATCH WINDER BOX ALL THE WATCH WINDER BOX USE THE FIRST GRADE JAPANESE MOTOR "MABUCHI" AND DESIGNED & MANUFACTURED BY JAPANESE COMPANY IN CHINA T06-IGM-Z105-3 SINGLE WATCH WINDER MATERIAL ; MDF WITH PU LEATHER COLOUR : RED SIZE MM : W148XH145XD160 WEIGHT g : 950 Power AC:100V-240V 4PCS PER CARTON T06-IGM-Z105-19 SINGLE WATCH WINDER MATERIAL ; MDF WITH PU LEATHER COLOUR : BROWN SIZE MM : W148XH145XD160 WEIGHT g : 950 Power AC:100V-240V 4PCS PER CARTON T06-IGM-Z104-5 SINGLE WATCH WINDER MATERIAL ; MDF WITH PU LEATHER COLOUR : YELLOW SIZE MM : W148XH146XD162 WEIGHT g : 950 Power AC:100V-240V 4PCS PER CARTON T06-IGM-Z111-5 MATERIAL : MEDIUM DENSITY FIBREBOARD SINGLE WATCH WINDER COLOUR : CHERRY SIZE MM : W128XH140XD128 WEIGHT g : 850 Power AC:100V-240V 4PCS PER CARTON T06-IGM-Z106-18BK SINGLE WATCH WINDER MATERIAL : MEDIUM DENSITY FIBREBOARD COLOUR : BLACK SIZE MM : W145XH145XD150 WEIGHT g : 1000 T06-IGM-Z106-18GR COLOUR : GRAY SIZE MM : W145XH145XD150 Power AC:100V-240V 4PCS PER CARTON WEIGHT g : 1000 WATCHWINDER CATALOGUE 1 T06-IGM-Z102-5 SINGLE WATCH WINDER MATERIAL : MEDIUM DENSITY FIBREBOARD COLOUR : WOODEN GRAIN SIZE MM : W145XH150XD145 WEIGHT g : 1000 Power AC:100V-240V 4PCS PER CARTON T06-IGM-Z109-1 SINGLE WATCH WINDER MATERIAL : MDF WITH ASH VEENER IN MATT COLOUR : BLACK 4PCS PER CARTON SIZE MM : W145XH150XD145 WEIGHT g : 900 Power AC:100V-240V T06-IGM-Z112-5 SINGLE WATCH WINDER MATERIAL : MDF WITH WOOD VENEER COLOUR : BROWN SIZE MM : W145WH145XD150 WEIGHT g : 1400 Power AC:100V-240V 4PCS PER CARTON T06-IGM-Z107-1 TWO WATCH -

Watch Parts Assortment

WATCH PARTS KIT ASSORTMENTS SECTION 1) WATCH BANDS PARTS SUB SECTION 1.1) PIN, T-BARS, SCREW, SPRING BAR AB-605ASS20-1.00 SLIM TYPE, 1.0MM DIAMETER STAINLESS STEEL SPRING BAR ASSORTMENT OLD REF : T-605-ASS20/1.0 SIZE AND QUANTITY AS FOLLOWS, 6MM 7MM 8MM 9MM 10MM 11MM 12MM 14MM 16MM 18MM 20MM 22MM EACH 20PCS AND 12 SIZES, TOTAL 240PCS REFILL CODE : RF-605ASS20/1.0-SIZE REFILL PACKING : 20PCS PER BOX 50PCS PER BOX 100PCS PER BOX 1000PCS PER PACK AB-605SDF120S DOUBLE FLANGE , DIA. 1.20MM T-605SDF120 STAINLESS STEEL SPRING BAR ASSORTMENT SIZES AND QUANTITY AS FOLLOWS, 7MM, 8MM, 9MM, 10MM, 11MM,12MM,13MM,14MM, 15MM 16MM, 17MM, 18MM, 19MM, 20MM, 21MM, 22MM, 23MM, 24MM EACH 20PCS, TOTAL 18 SIZES AND 360PCS REFILLS : 20PCS/BAG MIN 50BAGS 50PCS/BAG, MIN. 20 BAGS AB-605ASS20-1.50 STAINLESS STEEL SPRING BARS ASSORTMENT SIZE AND QUANTITY AS FOLLOWS, T-605-ASS20/1.50 6MM, 7MM, 8MM, 9MM, 10MM, 11MM, 13MM, 14MM, 15MM, 16MM 17MM, 19MM, 20MM, 21MM, 22MM EACH 20PCS THE MOST POPULAR SIZE 12MM AND 18MM WITH 40PCS EACH SPECIAL UNIVERAL SIZE 16-21MM : 20PCS TOATL 18 SIZES AND 400PCS IN ONE ASSORTMENT AB-605ASS20-1.30 SIZE AND QUANTITY AS 605ASS20-1.50, T-605ASS20/1.30 BUT DIAMETER IN 1.30MM AB-605ASS20-1.78 SIZE AS 605ASS20/1.50, BUT DIAMETER IN 1.78MM T-605ASS20/1.78 QUANTITY FOR 12MM AND 18MM ARE ONLY 30PCS, BOX SIZE : 6.5X11X1.5CM TOTAL 18SIZES AND 380PCS AB-605ASS50-1.50 BIGGER S/S SPRING BAR KIT T-605ASS50/1.50 SIZE AND QUANTITY AS FOLLOWS, 6MM, 7MM, 8MM, 9MM, 10MM, 11MM, 13MM, 14MM, 15MM, 16MM 17MM, 19MM, 20MM, 21MM, 22MM EACH 50PCS THE MOST POPULAR -

Dimensional Investment Group

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2008-04-29 | Period of Report: 2008-02-29 SEC Accession No. 0001104659-08-027772 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC/ Business Address 1299 OCEAN AVE CIK:861929| IRS No.: 000000000 | State of Incorp.:MD | Fiscal Year End: 1130 11TH FLOOR Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-06067 | Film No.: 08784216 SANTA MONICA CA 90401 2133958005 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number 811-6067 DIMENSIONAL INVESTMENT GROUP INC. (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Catherine L. Newell, Esquire, Vice President and Secretary Dimensional Investment Group Inc., 1299 Ocean Avenue, Santa Monica, CA 90401 (Name and address of agent for service) Registrant's telephone number, including area code: 310-395-8005 Date of fiscal year end: November 30 Date of reporting period: February 29, 2008 ITEM 1. SCHEDULE OF INVESTMENTS. Dimensional Investment Group Inc. Form N-Q February 29, 2008 (Unaudited) Table of Contents Definitions of Abbreviations and Footnotes Schedules of Investments U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio II U.S. Large Cap Value Portfolio III LWAS/DFA U.S. High Book to Market Portfolio DFA International Value Portfolio Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. -

Information on the Company 1

Information on the Company 1. Overview of the business group Epson is primarily engaged in developing, manufacturing, selling, and providing services for products in the printing solutions, visual communications, wearable and industrial products, and the other business. Epson is organized into operations divisions that come under global consolidated management. The majority of advanced R&D and product development is conducted in Japan (by Corporate R&D and R&D organizations in the various operations divisions), while manufacturing and sales activities are conducted around the world by Epson Group manufacturing and sales companies, both in Japan and abroad. A brief description of Epson’s various businesses is provided below along with a list of the main Epson Group companies involved in each segment. Printing Solutions Business Segment This segment comprises the printer business, professional printing business, and others. The businesses in this segment leverage Epson’s original Micro Piezo as well as dry fiber technology and other technologies to develop, manufacture, and sell products and provide services related thereto. The main activities of these businesses are described below. Printer business This business is primarily responsible for office and home inkjet printers, serial impact dot matrix (SIDM) printers, page printers, color image scanners, dry process office papermaking systems, and related consumables. Professional printing business This business is primarily responsible for inkjet printers for commercial and industrial applications, printers for use in POS systems, inkjet printheads, and related consumables. Others This business sells PCs in the Japanese market through a domestic subsidiary. 4 The major Epson Group companies involved in this segment are listed in the table below. -

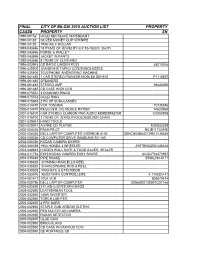

Final City of Biloxi 2010 Auction List Property Case

FINAL CITY OF BILOXI 2010 AUCTION LIST PROPERTY CASE# PROPERTY SN 199000152 GOLD NECKLACE W/PENDANT 199000152 SILVER MONEY CLIP W/KNIFE 199000152 1948 HALF DOLLAR 1992043696 18 ITEMS OF JEWELRY (EX:1015)(EX: 2527) 1992043696 PURSE & WALLET 1992043696 JACKET W/PANTS 1992043696 8 ITEMS OF CLOTHING 1996003945 CB RADIO UNIDEN PC33 63015526 1996035505 JEANS/VHS TAPE/2 CD'S/SUNGLASSES 1996035505 TELEPHONE ANSWERING MACHINE 1996061485 1 CAR STEREO PIONEER MODLE# DEH515 P1118557 1996061485 SPEAKERS 1996061485 STEREO AMP 93040266 1996061485 CD CASE W/59 CD'S 1999075552 2 DIAMOND RINGS 1999075552 GOLD RING 1999075553 2 PR OF SUNGLASSES 2000014470 VCR TOSHIBA 10735246 2000014470 RECEIVER JVC MODLE RX705V 146C0960 2001016100 CAR STEREO CLARION PRO AUDIO MD#DXR9375R 0.0003978 2001016100 7 ITEMS OF JEWELRYGOLD&SILVER CHAIN 2001029041 HAND TOOLS 2001029041 ALPINE CD PLAYER M30933239 2002008326 PALM PILOT B0JB11T2254E 2002008326 DELL LAPTOP COMPUTER INSPIRON 8100 DSNCN03N6421296121J6345 2002008326 CD COMPUTER DRIVE SAMSUNG SC140 2002008326 KODAK CAMERA DX3900 2002060399 1983 HONDA 3 WHEELER JHSTB0502DC246328 2003048663 HIDDEN WALL SAFE & FOOD SAVER, SEALER 2004011758 EX12 KODAK CAMERA EASY SHARE KCGCP34373597 2004035489 PIPE SNAKE S55KLHN6171 2004035825 SHIMANO MARLELLO REEL 2004035825 SHAKESPEARE ROD & REEL 2004039303 RACHETE & EXTENSION 2004050076 XBOX WITH CONTROLLERS 4.11432E+11 2004061411 RCA VCR 802570414 2005000796 DELL LAPTOP COMPUTER .00066902128007CD1166 2005002850 2 FLASHLIGHTS MINI MAGS 2005002850 -

CDP Japan 500 Climate Change Report 2018

DISCLOSURE INSIGHT ACTION CDP Japan 500 Climate Change Report 2018 On behalf of 658 investors with assets of US$87 trilllion CDP Report 2018 | May 2019 Report writer 02 Contents CEO Foreword 4 Forewords from Report Writers 5 The Climate A List 2018 8 Scoring Methodology 10 CLIMETRICS 11 CPR Invest 12 Story of Change - Japan Tobacco 14 Japanese Company response to CDP 2018 16 Carbon Pricing in Japanese Company 22 CDP and TCFD 25 The Japan Climate Initiative (JCI) 26 CDP Cities 28 Message form the Minister of the Environment 30 Appendix: CDP Climate Change 2018 -Japanese 32 Company Important Notice The contents of this report may be used by anyone providing acknowledgement is given to CDP Worldwide (CDP). This does not represent a license to repackage or resell any of the data reported to CDP or the contributing authors and presented in this report. If you intend to repackage or resell any of the contents of this report, you need to obtain express permission from CDP before doing so. CDP have prepared the data and analysis in this report based on responses to the CDP 2016 information request. No representation or warranty (express or implied) is given by CDP as to the accuracy or completeness of the information and opinions contained in this report. You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. To the extent permitted by law, CDP do not accept or assume any liability, responsibility or duty of care for any consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance on the information contained in this report or for any decision based on it. -

Digital Image Innovation ~ Targeting the Convergence of Imaging Domains ~ SEIKO EPSON CORPORATION

ANNUAL REPORT 2004 SEIKO EPSON CORPORATION ANNUAL REPORT 2004 Digital Image Innovation ~ Targeting the Convergence of Imaging Domains ~ SEIKO EPSON CORPORATION A Leader in Digital Imaging Epson is a leading name in the color printer, LCD projector, and small and medium-sized color LCD markets. Leveraging sophisticated and distinctive technology development capabilities and with a customer-oriented mindset, Epson has built a dominant pres- ence in fields where we have an advantage. Our solid position in these industries is founded on firm partnerships with some of the world’s best known companies. The foundation of Epson’s technology is the fusion of its production technology, ultra- precision processing technology, and our tireless pursuit of distinctive technology— which started out from the commercialization of quartz watches. This has been achieved by our distinctive development and production of our unrivaled low power consumption key devices. These base technologies are directly linked to the evolution and development of information-related equipment and electronic devices—the core elements of Epson’s current business foundation. Distinctive Strengths in Technology Development SEIKO EPSON CORPORATION 1 2 SEIKO EPSON CORPORATION Comprehensive Capabilities— From Key Devices to Finished Products Epson’s competitive edge in the market comes from the synergies of finished products and by developing and manufacturing key devices, which determines the competitive- ness of finished products. In LCD projectors, for example, Epson’s in-house capabilities in high-temperature polysilicon TFT LCD panels, a key device, and optical technology set us apart from competitors, allowing us to capture an overwhelming share of the global market. One of Epson’s strengths is software development capabilities that support strong finished products and key devices. -

Annual Report 2005 Seiko Epson Annual Report 2005 03

Seiko Epson Annual Report 2005 Seiko Epson Annual Report 2005 03 Exceed Your Vision You have the potential to create something with Epson that exceeds your vision. We strive to offer products and services that exceed your expectations. ©BAKU SAITO Epson—Striving to i1: imaging on paper i2: imaging on screen Responding to a range of professional needs, this By offering high-quality, large-screen viewing, this “Exceed Your Vision” high-quality inkjet printer is equipped with newly 3LCD projector for the home delivers a realistic developed K3 ink for monochrome and color prints and exciting theater experience. of exceptional quality. Refer to page 16 for more details. Refer to page 14 for more details. i3: imaging on glass i0: imaging support devices This ultra-thin LCD module shown at Display2005, Using proprietary applied inkjet-based manufactur- the first international flat-panel display Expo, is an ing technology, Epson created the world’s first*1 example of how developments at Epson are shaping ultra-thin printed circuit board prototype. This is a the future of mobile displays. product from Epson’s “pathfinder-style R&D” Refer to page 18 for more details. program for anticipating medium-to-long-term business developments. *1 Source: Seiko Epson Corporation Refer to page 20 for more details. How Will Epson “Exceed Your Vision” ? 04 Seiko Epson Annual Report 2005 Management Philosophy Epson is a progressive company, trusted throughout the world because of our commitment to customer satisfaction, environmental conservation, individuality, and teamwork. We are confident of our collective skills and meet challenges with innovative and creative solutions. -

Company Vendor ID (Decimal Format) (AVL) Ditest Fahrzeugdiagnose Gmbh 4621 @Pos.Com 3765 0XF8 Limited 10737 1MORE INC

Vendor ID Company (Decimal Format) (AVL) DiTEST Fahrzeugdiagnose GmbH 4621 @pos.com 3765 0XF8 Limited 10737 1MORE INC. 12048 360fly, Inc. 11161 3C TEK CORP. 9397 3D Imaging & Simulations Corp. (3DISC) 11190 3D Systems Corporation 10632 3DRUDDER 11770 3eYamaichi Electronics Co., Ltd. 8709 3M Cogent, Inc. 7717 3M Scott 8463 3T B.V. 11721 4iiii Innovations Inc. 10009 4Links Limited 10728 4MOD Technology 10244 64seconds, Inc. 12215 77 Elektronika Kft. 11175 89 North, Inc. 12070 Shenzhen 8Bitdo Tech Co., Ltd. 11720 90meter Solutions, Inc. 12086 A‐FOUR TECH CO., LTD. 2522 A‐One Co., Ltd. 10116 A‐Tec Subsystem, Inc. 2164 A‐VEKT K.K. 11459 A. Eberle GmbH & Co. KG 6910 a.tron3d GmbH 9965 A&T Corporation 11849 Aaronia AG 12146 abatec group AG 10371 ABB India Limited 11250 ABILITY ENTERPRISE CO., LTD. 5145 Abionic SA 12412 AbleNet Inc. 8262 Ableton AG 10626 ABOV Semiconductor Co., Ltd. 6697 Absolute USA 10972 AcBel Polytech Inc. 12335 Access Network Technology Limited 10568 ACCUCOMM, INC. 10219 Accumetrics Associates, Inc. 10392 Accusys, Inc. 5055 Ace Karaoke Corp. 8799 ACELLA 8758 Acer, Inc. 1282 Aces Electronics Co., Ltd. 7347 Aclima Inc. 10273 ACON, Advanced‐Connectek, Inc. 1314 Acoustic Arc Technology Holding Limited 12353 ACR Braendli & Voegeli AG 11152 Acromag Inc. 9855 Acroname Inc. 9471 Action Industries (M) SDN BHD 11715 Action Star Technology Co., Ltd. 2101 Actions Microelectronics Co., Ltd. 7649 Actions Semiconductor Co., Ltd. 4310 Active Mind Technology 10505 Qorvo, Inc 11744 Activision 5168 Acute Technology Inc. 10876 Adam Tech 5437 Adapt‐IP Company 10990 Adaptertek Technology Co., Ltd. 11329 ADATA Technology Co., Ltd. -

Citizen Group CSR Report 2009

Citizen Group CSR Report 2009 Special Feature The Citizen Group’s Approach to Manufacturing: Good for People and the Planet Bringing the Eco-Drive solar-powered watch to our customers Message from Management Internal Audit & CSR Department at Citizen Holdings Co., Ltd. 6-1-12 Tanashi-cho, Nishitokyo, Tokyo 188-8511, Japan Establishing the human and Tel: +81-42-468-4776 Fax: +81-42-466-1280 organizational strength to Citizen website: http://www.citizen.co.jp/english/ adapt to future changes Published: June 2009 This report uses FSC-certified paper. This certification means that the paper is made using wood from forests managed appropriately in environmental, social, and economic terms. This paper is printed with CTP printing technology, which reduces the burden on the environment by avoiding film that uses developers. Waterless printing with no release of toxic effluents has been used. This report also uses highly biodegradable and de-inkable soy ink that facilitates the recycling of printed matter. Citizen is a registered trademark of Citizen Holdings Co., Ltd. CONTENTS Editorial Policy The aim of this publication, CSR Report 2009, is to provide all of our stakeholders with a straight forward outline of the Citizen Group’s Editorial Policy 2 business activities and the Group’s approach and initiatives in relation to its social responsibilities. The Citizen Group 3 The Special Feature section examines the process of bringing the Eco-Drive solar powered watch, one of our environmentally friendly Citizen Products and Technology products, to our customers, incorporating the thoughts of employees involved in business activities along the way. -

Involving Epson and Wholly-Owned Subsidiary Company

Notification of Company Split (Simple Absorption Type) Involving Epson and Wholly-Owned Subsidiary Company - TOKYO, Japan, January 31, 2017 - Seiko Epson Corporation (TSE: 6724, “Epson”) today resolved to absorb part of the business of subsidiary company Orient Watch Co., Ltd. (“Orient Watch”), with Epson to continue as the succeeding company. Certain information has been omitted from this announcement since the company split involves a wholly-owned subsidiary company. 1. Purpose of the company split As disclosed in the announcement of September 6, 2016, Epson has been continuing discussions on the restructuring of Orient Watch business. As a result, Epson has decided to absorb the watch sales function of Orient Watch (excluding Japan domestic sales) with the aim of further reinforcing its operational capabilities by optimizing the allocation of management resources within the Epson Group. The domestic sales business of Orient Watch will be succeeded by Epson Sales Japan Corporation. Going forward, Epson will absorb the strengths of Orient Watch as it seeks to accelerate the growth of its wearables business to achieve its goal of realizing the wearables innovation raised in its Epson 25 long-range corporate vision, and create wearable products that offer original and indispensable value to its customers. 2. Outline of the company split (1) Schedule for the company split Resolution of the company split January 31, 2017 Conclusion of company split contract January 31, 2017 Effective date of the company split April 1, 2017 (planned) Notes: 1. The company split will not require a shareholders’ meeting resolution from either company because the company split will be a simple absorption-type company split for Epson as stipulated in Article 796 (2) of the Companies Act, and a short-form absorption-type company split for Orient Watch as stipulated in Article 784 (1) of the Companies Act. -

Sa Funds Investment Trust

SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION FORM N-Q Quarterly schedule of portfolio holdings of registered management investment company filed on Form N-Q Filing Date: 2007-11-29 | Period of Report: 2007-09-30 SEC Accession No. 0001104659-07-086055 (HTML Version on secdatabase.com) FILER SA FUNDS INVESTMENT TRUST Mailing Address Business Address 3055 OLIN AVENUE SUITE 3055 OLIN AVENUE SUITE CIK:1075065| IRS No.: 770216379 | State of Incorp.:DE | Fiscal Year End: 0630 2000 2000 Type: N-Q | Act: 40 | File No.: 811-09195 | Film No.: 071275109 SAN JOSE CA 95128 SAN JOSE CA 95128 408-260-3100 Copyright © 2012 www.secdatabase.com. All Rights Reserved. Please Consider the Environment Before Printing This Document UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM N-Q QUARTERLY SCHEDULE OF PORTFOLIO HOLDINGS OF REGISTERED MANAGEMENT INVESTMENT COMPANY Investment Company Act file number 811-09195 SA Funds Investment Trust (Exact name of registrant as specified in charter) 3055 Olin Avenue, Suite 2000 San Jose, California 95128 (Address of principal executive offices) (Zip code) Steven K. McGinnis, Esq. Chief Legal Officer SA Funds Investment Trust 3055 Olin Ave., Suite 2000 San Jose, CA 95128 (Name and address of agent for service) Copies to: Julie Tedesco R. Darrell Mounts Senior Vice President and Senior Counsel Counsel to the Trust State Street Bank and Trust Company Kirkpatrick & Lockhart Preston Gates Ellis LLP 2 Avenue de Lafayette, 6th Floor 1601 K Street, N.W. Boston, Massachusetts 02111 Washington, D.C. 20006 Registrants Telephone Number, Including Area Code: (408) 260-3100 Date of fiscal year end: June 30 Date of reporting period: September 30, 2007 Item 1.