Blues Tourism in the Mississippi Delta: the Functions of Blues Festivals Stephen A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta Levee Board and Staff Wish the Citizens Of

\ Yazoo-Mississippi Delta Levee Board • HAPPY HOLIDAYS • President Sykes Sturdivant Receives Volunteer Service Award The Yazoo-Mississippi Delta Levee Board President Sykes Sturdivant was the recipient of Volunteer Yazoo-Mississippi Northwest Mississippi’s President’s Volunteer Service Award. The award, established by the President’s Delta Levee Board Council on Service and Civic Participation, was given to 25 outstanding volunteers from eight counties. The official publication of the Yazoo-Mississippi Delta Levee District WINTER 2010 Vol. 4, Number 1 Sturdivant has served as Levee Board president for and Staff 14 years. He is a long-time member of the West Tallahatchie Habitat for Humanity and serves on the FEMA Map Modernization Program Emmett Till Memorial Commission. wish the citizens Arrives in the Mississippi Delta of our region In fiscal year 2003, the Federal used by FEMA in their map moderniza- Dabney, a gray fox squirrel, lives in a tree behind Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) tion project are accurate to only 5.0 feet. the Levee Board Building and has become the ________Copywriter ________Copy Editor a safe and festive began a multiyear map modernization The Upper Yazoo Project is a federally . official Levee Board pet. project of Flood Insurance Rate Maps funded project which began actual con- (FIRM) under the National Flood struction near Yazoo City in 1976 and holiday season! Insurance program with a total cost of has progressed upstream to just south of $1.6 billion as appropriated by Congress. Mississippi Highway 32 in Tallahatchie Artist ________Art Dir These new maps are referred to as County. The project is designed to . -

Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682)

University of Mississippi eGrove Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids Library November 2020 Finding Aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection (MUM00682) Follow this and additional works at: https://egrove.olemiss.edu/finding_aids Recommended Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi This Finding Aid is brought to you for free and open access by the Library at eGrove. It has been accepted for inclusion in Archives & Special Collections: Finding Aids by an authorized administrator of eGrove. For more information, please contact [email protected]. University of Mississippi Libraries Finding aid for the Sheldon Harris Collection MUM00682 TABLE OF CONTENTS SUMMARY INFORMATION Summary Information Repository University of Mississippi Libraries Biographical Note Creator Scope and Content Note Harris, Sheldon Arrangement Title Administrative Information Sheldon Harris Collection Related Materials Date [inclusive] Controlled Access Headings circa 1834-1998 Collection Inventory Extent Series I. 78s 49.21 Linear feet Series II. Sheet Music General Physical Description note Series III. Photographs 71 boxes (49.21 linear feet) Series IV. Research Files Location: Blues Mixed materials [Boxes] 1-71 Abstract: Collection of recordings, sheet music, photographs and research materials gathered through Sheldon Harris' person collecting and research. Prefered Citation Sheldon Harris Collection, Archives and Special Collections, J.D. Williams Library, The University of Mississippi Return to Table of Contents » BIOGRAPHICAL NOTE Born in Cleveland, Ohio, Sheldon Harris was raised and educated in New York City. His interest in jazz and blues began as a record collector in the 1930s. As an after-hours interest, he attended extended jazz and blues history and appreciation classes during the late 1940s at New York University and the New School for Social Research, New York, under the direction of the late Dr. -

Blues in the 21St Century

Blues in the 21 st Century Myth, Self-Expression and Trans-Culturalism Edited by Douglas Mark Ponton University of Catania, Italy and Uwe Zagratzki University of Szczecin, Poland Series in Music Copyright © 2020 by the Authors. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior permission of Vernon Art and Science Inc. www.vernonpress.com In the Americas: In the rest of the world: Vernon Press Vernon Press 1000 N West Street, C/Sancti Espiritu 17, Suite 1200, Wilmington, Malaga, 29006 Delaware 19801 Spain United States Series in Music Library of Congress Control Number: 2019951782 ISBN: 978-1-62273-634-8 Product and company names mentioned in this work are the trademarks of their respective owners. While every care has been taken in preparing this work, neither the authors nor Vernon Art and Science Inc. may be held responsible for any loss or damage caused or alleged to be caused directly or indirectly by the information contained in it. Every effort has been made to trace all copyright holders, but if any have been inadvertently overlooked the publisher will be pleased to include any necessary credits in any subsequent reprint or edition. Cover design by Vernon Press. Cover image by Jean-Charles Khalifa. Cover font (main title): Free font by Tup Wanders. Table of contents List of Figures vii List of Tables ix Preface xi Acknowledgements xix Part One: Blues impressions: responding to the music 1 1. -

Mississippi-State of the Union

MISSISSIPPI-STATE OF THE UNION DURING THE PAST several years in which the struggle for human rights rights in our country has reached a crescendo level, the state of ~ississippi has periodically been a focal point of national interest. The murder of young Emmett Till, the lynching of Charles Mack Parker in the "moderate" Gulf section of Mississippi, the "freedom rides" to Jackson, the events at Oxford, Mississippi, and the triple lynching of the martyred Civil Rights workers, Chaney, Schwerner and Goodman, have, figuratively, imprinted Mississippi on the national conscience. In response to the national concern arising from such events, most writings about Mississippi have been in the nature of reporting, with emotional appeal and shock-value being the chief characteristics of such writing. FREEDOMWAYS is publishing this special issue on Mississippi to fill a need both for the Freedom Movement and the country. The need is for an in-depth analysis of Mississippi; of the political, economic and cultural factors which have historically served to institutionalize racism in this state. The purpose of such an analysis is perhaps best expressed in the theme that we have chosen: "Opening Up the Closed Society"; the purpose being to provide new insights rather than merely repeating well-known facts about Mississippi. The shock and embarrassment which events in Mississippi have sometimes caused the nation has also led to the popular notion that Mississippi is some kind of oddity, a freak in the American scheme-of-things. How many Civil Rights demonstrations have seen signs proclaiming-"bring Mississippi back into the Union." This is a well-intentioned but misleading slogan. -

Lightning in a Bottle

LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE A Sony Pictures Classics Release 106 minutes EAST COAST: WEST COAST: EXHIBITOR CONTACTS: FALCO INK BLOCK-KORENBROT SONY PICTURES CLASSICS STEVE BEEMAN LEE GINSBERG CARMELO PIRRONE 850 SEVENTH AVENUE, 8271 MELROSE AVENUE, ANGELA GRESHAM SUITE 1005 SUITE 200 550 MADISON AVENUE, NEW YORK, NY 10024 LOS ANGELES, CA 90046 8TH FLOOR PHONE: (212) 445-7100 PHONE: (323) 655-0593 NEW YORK, NY 10022 FAX: (212) 445-0623 FAX: (323) 655-7302 PHONE: (212) 833-8833 FAX: (212) 833-8844 Visit the Sony Pictures Classics Internet site at: http:/www.sonyclassics.com 1 Volkswagen of America presents A Vulcan Production in Association with Cappa Productions & Jigsaw Productions Director of Photography – Lisa Rinzler Edited by – Bob Eisenhardt and Keith Salmon Musical Director – Steve Jordan Co-Producer - Richard Hutton Executive Producer - Martin Scorsese Executive Producers - Paul G. Allen and Jody Patton Producer- Jack Gulick Producer - Margaret Bodde Produced by Alex Gibney Directed by Antoine Fuqua Old or new, mainstream or underground, music is in our veins. Always has been, always will be. Whether it was a VW Bug on its way to Woodstock or a VW Bus road-tripping to one of the very first blues festivals. So here's to that spirit of nostalgia, and the soul of the blues. We're proud to sponsor of LIGHTNING IN A BOTTLE. Stay tuned. Drivers Wanted. A Presentation of Vulcan Productions The Blues Music Foundation Dolby Digital Columbia Records Legacy Recordings Soundtrack album available on Columbia Records/Legacy Recordings/Sony Music Soundtrax Copyright © 2004 Blues Music Foundation, All Rights Reserved. -

Chicago Blues Festival Millennium Park + Citywide Programs June 7-9, 2019

36th Annual Chicago Blues Festival Millennium Park + Citywide Programs June 7-9, 2019 Open Invitation to Cross-Promote Blues during 36th Annual Chicago Blues Festival MISSION The Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events (DCASE) is dedicated to enriching Chicago’s artistic vitality and cultural vibrancy. This includes fostering the development of Chicago’s non-profit arts sector, independent working artists and for-profit arts businesses; providing a framework to guide the City’s future cultural and economic growth, via the Chicago Cultural Plan; marketing the City’s cultural assets to a worldwide audience; and presenting high-quality, free and affordable cultural programs for residents and visitors. BACKGROUND The Chicago Blues Festival is the largest free blues festival in the world and remains the largest of Chicago's music festivals. During three days on seven stages, blues fans enjoy free live music by top-tier blues musicians, both old favorites and the up-and-coming in the “Blues Capital of the World.” Past performers include Bonnie Raitt, the late Ray Charles, the late B.B. King, the late Bo Diddley, Buddy Guy, the late Koko Taylor, Mavis Staples, Shemekia Copeland, Gary Clark Jr, Rhiannon Giddens, Willie Clayton and Bobby Rush. With a diverse line-up celebrating the Chicago Blues’ past, present and future, the Chicago Blues Festival features live music performances of over 60 local, national and international artists and groups celebrating the city’s rich Blues tradition while shining a spotlight on the genre’s contributions to soul, R&B, gospel, rock, hip-hop and more. AVAILABLE OPPORTUNITY In honor of the 36th Annual Chicago Blues Festival in 2019, DCASE will extend an open invitation to existing Blues venues and promoters to have their event marketed along with the 36th Annual Chicago Blues Festival. -

May-June 293-WEB

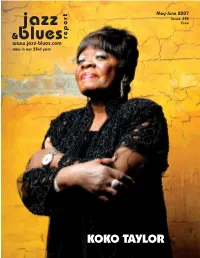

May-June 2007 Issue 293 jazz Free &blues report www.jazz-blues.com now in our 33rd year KOKO TAYLOR KOKO TAYLOR Old School Published by Martin Wahl A New CD... Communications On Tour... Editor & Founder Bill Wahl & Appearing at the Chicago Blues Festival Layout & Design Bill Wahl The last time I saw Koko Taylor Operations Jim Martin she was a member of the audience at Pilar Martin Buddy Guy’s Legends in Chicago. It’s Contributors been about 15 years now, and while I Michael Braxton, Mark Cole, no longer remember who was on Kelly Ferjutz, Dewey Forward, stage that night – I will never forget Chris Hovan, Nancy Ann Lee, Koko sitting at a table surrounded by Peanuts, Wanda Simpson, Mark fans standing about hoping to get an Smith, Dave Sunde, Duane Verh, autograph...or at least say hello. The Emily Wahl and Ron Weinstock. Queen of the Blues was in the house that night...and there was absolutely Check out our costantly updated no question as to who it was, or where website. Now you can search for CD Reviews by artists, titles, record she was sitting. Having seen her elec- labels, keyword or JBR Writers. 15 trifying live performances several years of reviews are up and we’ll be times, combined with her many fine going all the way back to 1974. Alligator releases, it was easy to un- derstand why she was engulfed by so Koko at the 2006 Pocono Blues Festival. Address all Correspondence to.... many devotees. Still trying, but I still Jazz & Blues Report Photo by Ron Weinstock. -

Jazz in America • the National Jazz Curriculum the Blues and Jazz Test Bank

Jazz in America • The National Jazz Curriculum The Blues and Jazz Test Bank Select the BEST answer. 1. Of the following, the style of music to be considered jazz’s most important influence is A. folk music B. the blues C. country music D. hip-hop E. klezmer music 2. Of the following, the blues most likely originated in A. Alaska B. Chicago C. the Mississippi Delta D. Europe E. San Francisco 3. The blues is A. a feeling B. a particular kind of musical scale and/or chord progression C. a poetic form and/or type of song D. a shared history E. all of the above 4. The number of chords in a typical early blues chord progression is A. three B. four C. five D. eight E. twelve 5. The number of measures in typical blues chorus is A. three B. four C. five D. eight E. twelve 6. The primary creators of the blues were A. Africans B. Europeans C. African Americans D. European Americans E. Asians 7. Today the blues is A. played and listened to primarily by African Americans B. played and listened to primarily by European Americans C. respected more in the United States than in Europe D. not appreciated by people outside the United States E. played and listened to by people all over the world 8. Like jazz, blues is music that is A. planned B. spontaneous C. partly planned and partly spontaneous D. neither planned nor spontaneous E. completely improvised 9. Blues lyrical content A. is usually secular (as opposed to religious) B. -

Cultural Resources Overview

United States Department of Agriculture Cultural Resources Overview F.orest Service National Forests in Mississippi Jackson, mMississippi CULTURAL RESOURCES OVERVIEW FOR THE NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI Compiled by Mark F. DeLeon Forest Archaeologist LAND MANAGEMENT PLANNING NATIONAL FORESTS IN MISSISSIPPI USDA Forest Service 100 West Capitol Street, Suite 1141 Jackson, Mississippi 39269 September 1983 TABLE OF CONTENTS Page List of Figures and Tables ............................................... iv Acknowledgements .......................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................... 1 Cultural Resources Cultural Resource Values Cultural Resource Management Federal Leadership for the Preservation of Cultural Resources The Development of Historic Preservation in the United States Laws and Regulations Affecting Archaeological Resources GEOGRAPHIC SETTING ................................................ 11 Forest Description and Environment PREHISTORIC OUTLINE ............................................... 17 Paleo Indian Stage Archaic Stage Poverty Point Period Woodland Stage Mississippian Stage HISTORICAL OUTLINE ................................................ 28 FOREST MANAGEMENT PRACTICES ............................. 35 Timber Practices Land Exchange Program Forest Engineering Program Special Uses Recreation KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE FOREST........... 41 Bienville National Forest Delta National Forest DeSoto National Forest ii KNOWN CULTURAL RESOURCES ON THE -

Hegemony in the Music and Culture of Delta Blues Taylor Applegate [email protected]

University of Puget Sound Sound Ideas Summer Research 2013 The crossroads at midnight: Hegemony in the music and culture of Delta blues Taylor Applegate [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research Part of the African American Studies Commons, American Popular Culture Commons, Cultural History Commons, and the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Applegate, Taylor, "The crossroads at midnight: Hegemony in the music and culture of Delta blues" (2013). Summer Research. Paper 208. http://soundideas.pugetsound.edu/summer_research/208 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Sound Ideas. It has been accepted for inclusion in Summer Research by an authorized administrator of Sound Ideas. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Crossroads at Midnight: Hegemony in the Music and Culture of Delta Blues Taylor Applegate Advisor: Mike Benveniste Summer 2013 INTRODUCTION. Cornel West’s essay “On Afro-American Music: From Bebop to Rap” astutely outlines the developments in Afro-American popular music from bebop and jazz, to soul, to funk, to Motown, to technofunk, to the rap music of today. By taking seriously Afro-American popular music, one can dip into the multileveled lifeworlds of black people. As Ralph Ellison has suggested, Afro-Americans have had rhythmic freedom in place of social freedom, linguistic wealth instead of pecuniary wealth (West 474). And as the fount of all these musical forms West cites “the Afro-American spiritual-blues impulse,” the musical traditions of some of the earliest forms of black music on the American continent (474). The origins of the blues tradition, however, are more difficult to pin down; poor documentation at the time combined with more recent romanticization of the genre makes a clear, chronological explanation like West’s outline of more recent popular music impossible. -

Why Am I Doing This?

LISTEN TO ME, BABY BOB DYLAN 2008 by Olof Björner A SUMMARY OF RECORDING & CONCERT ACTIVITIES, NEW RELEASES, RECORDINGS & BOOKS. © 2011 by Olof Björner All Rights Reserved. This text may be reproduced, re-transmitted, redistributed and otherwise propagated at will, provided that this notice remains intact and in place. Listen To Me, Baby — Bob Dylan 2008 page 2 of 133 1 INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................................................. 4 2 2008 AT A GLANCE ............................................................................................................................................................. 4 3 THE 2008 CALENDAR ......................................................................................................................................................... 5 4 NEW RELEASES AND RECORDINGS ............................................................................................................................. 7 4.1 BOB DYLAN TRANSMISSIONS ............................................................................................................................................... 7 4.2 BOB DYLAN RE-TRANSMISSIONS ......................................................................................................................................... 7 4.3 BOB DYLAN LIVE TRANSMISSIONS ..................................................................................................................................... -

Bowlography of Rock and Pop Concerts

BOWLOGRAPHY OF ROCK AND POP CONCERTS 1979 DESMOND DECKER with Geno Washington, Sat 8th September 1980 POLICE with Squeeze, UB40, Skatfish, Sector 27, Sat 26th July 1981 THIN LIZZY with Judie Tzuke, The Ian Hunter Band, Q Tips, Trimmer and Jenkins,Sat 8th August 1982 QUEEN, with Heart, Teardrop Explodes, Joan Jett and the Blackhearts, Sat 5th June GENESIS, with Talk Talk, The Blues Band, John Martyn, Sat 2nd October 1983 DAVID BOWIE, with The Beat and Icehouse Fri 1st, Sat 2nd, Sun 3rd July 1984 STATUS QUO with Marillion, Nazareth, Gary Glitter, Jason and the Scorchers, Sat 21st July 1985 U2 with REM, The Ramones, Billy Bragg, Spear Of Destiny, The Men They Couldn’t Hang, Faith Brothers, Sat 22nd June 1986 SIMPLE MINDS with The Bangles, The Cult, Lloyd Cole and The Commotions, Big Audio Dynamite, The Waterboys, In Tua Nua, Dr and The Medics, Sat 21st June MARILLION with special guests, Gary Moore, Jethro Tull, Magnum, Mamas Boys, Sat 28th June 1988 Amnesty International event with Stranglers, Aswad, The Damned, Howard Jones, Joe Strummer, Aztec Camera, B.A.D, Sat 18th, Sun 19th June MICHAEL JACKSON, with Kim Wilde, Sat 10th September 1989 BON JOVI with Europe, Vixen and Skid Row, Sat 19th August 1990 DAVID BOWIE, with Gene Loves Jezebel, The Men They Couldn’t Hang, Two Way Street, Sat 4th, Sun 5th August ERASURE, with Adamski, Sat 1st September 1991 ZZ TOP with Bryan Adams, Liitle Angels, The Firm, Thunder Sat 6th July SIMPLE MINDS, with Stranglers, OMD Sat 21st August 1993 BRUCE SPRINGSTEEN, Sat 23rd May GUNS 'n’ ROSES, The Cult, Soul